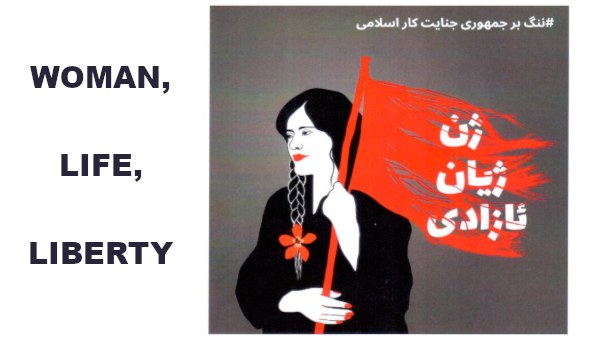

Women, Life, Liberty: A Protest Promising a Revolution to End All Oppression and Exploitation

The song Baraye (For) composed by the singer Shervin Hajipour has been described as “the anthem” of the “Women, Life, Liberty” protests in Iran. Hajipour wrote the lyrics using a collection of tweets by the protesters. Shortly after the release of Baraye, he was arrested. However, he has been released on bail. As such, the lyrics offer a random sample of what motivates some of the protesters. To keep the authenticity of these, the following is my literal English translation of the lyric, which sacrifices it musical and poetic forms.

Baraye (For)

For the sake of dancing in the street

For the fear felt in the moment of kissing

For my sister, your sister, our sisters

For changing the rotten minds

For shame, for pennilessness

For the yearning for an ordinary life

For the sake of the children that mine the garbage and their dreams

For this government-run economy

For this polluted air

For Vali-Asr street and its dying trees

For Piruz, the cheetah cub and his imminent extinction

For the banned innocent dogs

For nonstop weeping

For imagining the repeat of this moment

For a laughing face

For the students, for the future

For this compulsory paradise

For the imprisonment of educated intellects

For the Afghani children

For all these never repeated fors

For all the hollow slogans

For the collapse of the chaffy houses

For tranquillity

For the sun after the endless night

For tranquilizers and insomnia

For men, country, prosperity

For that girl who wished to be a boy

For women, life, liberty

For liberty.

The Protests

The death of Mahsa Amini, the 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman in the custody of the Islamic Republic morality police in Tehran on September 16, 2022, has ignited ongoing protests. With a population of 86.3 million and a median age of 32, street protests have been mainly organized and attended by young people, including many young women. Some college campuses and high school students have joined, especially women and girls. Women’s protests have included the symbolic removal of the 42-year-old compulsory headscarves. Some women have burned their headscarves, and some, in a symbolic act, have cut pieces of their hair in public protests.

There has been growing mass support for the protests, including a growing number of solidarity labour strikes including in the oil and gas, petrochemical, and steel industries. The Islamic Republic has been losing support even among the religious sectors of society, as was in full display in the October 13 security forces attack on Shahed High School in Ardabil, Azerbaijan. The school is part of the network run by the Shaheed (Martyr) Foundation. These schools are dedicated to the students who are typically children of those who died or were critically wounded in the Iran-Iraq war. Video recordings of the students’ protest show them wearing the full black chador typical of practicing Muslim women. Officials had tried to force the students to sing in a pro-government show, “Salam Farmandeh,” a pledge of allegiance to the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei. Instead, a group of students chanted, “Death to the Dictator!” Nineteen students were arrested, and ten were injured. One student was killed.

Energized by the protests in Iran, solidarity rallies and marches have been organized in many cities worldwide by expatriate Iranians. The protests in Iran have also won the solidarity of many non-Iranians worldwide, especially women. Very creative solidarity art and music developed in Iran and elsewhere have been posted and shared on social media.

The Islamic Republic does not seem to be able to stop the protests, and the young protesters promise not to return to passivity. It is a matter of time before broader layers of Iranians take to the streets. When millions mobilize in the streets, and a mass general strike happens, especially in critical industries like oil and gas, the days of the theocratic capitalist rule in Iran are numbered. The strategic question is: what will replace it?

The current protests reject the Islamic Republic regime in its totality. Some commentators see the present demonstrations in continuity with earlier ones going back to the Green Movement in 2009. However, the Green Movement gave political support to two presidential candidates, Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, of the reformist wing of the Islamic Republic.

Other commentators have called these protests a revolution. That is an overstatement. It is true that a fast-growing section of the population is being mobilized to support these young fighters, including an unfolding wave of solidarity labour strikes. However, there has not been any mass street protests to challenge the regime and a nationwide general strike, not to mention publicly organized grassroots movements of the crucial sectors of the population. Street protests in Tehran have been limited to after-business hours as daily life seems to go on.

The 1979 Revolution

While every revolution is unique, it is helpful to consider the 1979 revolution when Iran had a population of 36 million (for a political summary of the lessons of the 1979 revolution, see Nayeri and Nassab 2006). A convenient way to mark the beginning of the revolution is the February 1978 demonstration of a few hundred thousand in Tabriz, Azerbaijan. It was then followed with some regularity mass demonstrations in other cities. By the summer of 1978, these were supported by a general strike of workers, including government office employees. Workplace strike committees were formed. On December 10 and 11, 1978, under martial law conditions, as many as 17 million Iranians took to the streets in many cities, including the most populous, as the oil workers staged a general strike. In neighborhoods, local committees were formed to distribute heating and cooking fuel that oil workers made sure to get to the public but denied to the government.

In combination, these divided the conscript ranks of the Shah’s army and demoralized its officers rendering martial law ineffective. The Shah was forced to flee the country on January 16 after setting up a caretaker cabinet with Shahpour Bakhtiar, a nationalist, as its prime minister. The February 1979 insurrection was the final blow to the American-installed and supported dictatorship of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi regime as the youth and sections of the army resisted an attempted military coup by the high brass. In three days, insurrections destroyed all repressive organs of the Shah’s regime across the country, beginning in Tehran on February 11.

It is helpful to recall the fatal weaknesses of the 1979 revolution. The central slogan of “Death to the Shah” united Iranians of all political persuasions against the regime. However, there was little discussion among the revolutionary masses and even in the socialist and labour movement about what kind of society we wanted to build after the overthrow of the Shah’s regime.

Although the 1979 revolution provided us with a surprisingly rich set of self-organization and self-mobilization of workers, oppressed nationalities, peasants, neighborhoods, and students, the idea of the bottom-up direct democracy as a form of government that would act on the immediate and long-term needs of the working people did not get much attention.

Instead, the masses rallied around existing opposition forces. The charismatic Ayatollah Khomeini, with a history of opposition to the Shah’s regime and the support of a network of clergy and mosques, became the acknowledged leader of the revolution. As the left was heavily influenced by the Stalinist ideology of the two-stage revolution, it did precious little to dispel the illusion in Khomeini and offer an alternative. Instead, the main Stalinist current, Tudeh Party, with the most experience and infrastructure, actually spread this illusion. Thus, most of the left identified Ayatollah Khomeini as the representative of the ‘national bourgeoisie’, who they argued should lead the anti-imperialist bourgeois-democratic revolution. In the interest of ‘unity’, even the non-Stalinist left ignored that Khomeini opposed the Shah from a reactionary position: his opposition to the extension of the right to vote to women and land reform. His ‘anti-imperialism’ was because of his pan-Shiism, not the international solidarity of the working people and anti-capitalism.

Thus, the principle of self-organization and self-mobilization of the working people was undermined by the left as even the non-Stalinist currents still believed that the future of the revolution would depend on their vanguard party to lead the masses, ignoring the creative potential of self-organized and self-mobilized shoras (workers’ councils) movement (which undoubtedly had weaknesses). Even leftist currents that aimed to be independent of the Islamic Republic substituted themselves for the actual mass movement. Some turned to ‘armed struggle’ against the regime despite mass illusion in Khomeini. Today, we must acknowledge these errors and make the lessons of 1979 a basis for our work to develop a politically independent and self-reliant mass movement of the youth and working people.

There is also a key difference today compared to 1979. In the past four decades, the world has become aware of existential ecological crises: catastrophic climate change, the Sixth Extinction, recurrent pandemics, and the nuclear holocaust. Regionally, there would be an unfolding crisis of freshwater scarcity as governments compete to make clouds rain in ‘their country’ by seeding them, a questionable technology. Within 20 years, freshwater would be rationed in Iran. Dust storms, air pollution, and over-populated heated cities are now a norm in Iran. Much of the Middle East, including large sections of southern Iran, will become uninhabitable (Alaaldin, 2022). The future of the Iranian people depends on rapid response and effective responses to these ecological crises. As we know from 50 years of no action by the capitalist world governments, especially in key polluting countries including Iran.

It is also imperative to critically review the history of the world revolution, beginning with the Russian revolution (Nayeri, 2022).

Women, Life, Liberty

The slogan “Women, Life, Liberty” offers the political maturity of the current movement compared to the 1979 revolution. Not only does it place the oppression of women in Iran front and center, but it also provides a framework to think about the kind of society we need to build after overcoming the current regime. When Ayatollah Khomeini declared on March 7, 1979, less than a month after the overthrow of the Shah’s regime and the day before International Women’s day on March 8, that women should wear hijab to enter government offices, it provoked thousands of women and many men to protest for three days. After a planned rally in front of Tehran University, a majority decided to march to Freedom Square. Some, mostly men, quickly created a defensive chain around the marchers as the newly organized Hezbollah goons attacked the marchers with sticks, chains, and knives. Despite a heroic effort by the marchers to proceed to the end, the crowd was dispersed well before reaching Azadi Square.

There were also protest rallies of a similar size, one at the prime minister’s office. But the millions who overthrew the Shah’s regime did not join us in the street to protest the beginning of what came to be compulsory hijab in Iran. What is worse, just three weeks later, on 30 and 31 March, 98.2% of eligible citizens, according to official results, voted for the Islamic Republic. There was no mass protest against the undemocratic referendum, which posed an artificially polar choice: the Islamic Republic or monarchy. Nobody knew what the Islamic Republic was supposed to look like, as its constitution was drafted by an Assembly of Experts in Islamic jurisprudence between August 3 and October 4 when it was approved.

The central slogan of the current protest has its origin in the Kurdish women’s movement in the Middle East in the 2000s as ژن، ژیان، ئازادی (pronounced Jin, Jiyan, Azadî; Women, Life, Liberty). It was adopted in the Iranian Kurdistan in response to Mahsa Amini’s death and was quickly adopted in its Farsi translation (زن زندگی ٱزادی, pronounced “Zan, Zendegi, Azadi”) nationwide. It has been also translated into other languages and chanted worldwide. The theoretical framework is Abdullah Öcalan’s concept of Jineology, a form of radical feminism, to achieve gender equality in a future independent democratic Kurdistan.

Born in 1949, Öcalan is a founding member of Turkey’s Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). He has been a political prisoner there since 1999. In prison, Öcalan shed his Stalinist ideology in prison after studying social theorists, including Murray Bookchin, Immanuel Wallerstein, and Hannah Arendt. By 2004, he advocated a “democratic con-federalism” for an independent Kurdistan based on a system of municipal assemblies fashioned after Bookchin’s The Ecology of Freedom: The emergence and dissolution of hierarchy (1982).

Critical of the Marxist mode of the production-centered theory of history, Bookchin proposed a more nuanced social analysis:

“My use of the word hierarchy in the subtitle of this work is meant to be provocative. There is a strong theoretical need to contrast hierarchy with the more widespread use of the words class and State; careless use of these terms can produce a dangerous simplification of social reality. To use the words hierarchy, class, and State interchangeably, as many social theorists do, is insidious and obscurantist. This practice, in the name of a ‘classless’ or ‘libertarian’ society, could easily conceal the existence of hierarchical relationships and a hierarchical sensibility, both of which – even in the absence of economic exploitation or political coercion – would serve to perpetuate unfreedom” (Bookchin 1982, p. 3).

Jineology

Öcalan describes jineology as follows:

“The extent to which society can be thoroughly transformed is determined by the extent of the transformation attained by women. Similarly, the level of woman’s freedom and equality determines the freedom and equality of all sections of society… For a democratic nation, woman’s freedom is of great importance too, as a liberated woman constitutes a liberated society. A liberated society, in turn, constitutes a democratic nation. Moreover, the need to reverse the role of man is of revolutionary importance” (cited in Düzgün, 2016).

During the Syrian civil war, The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), also known as Rojava, was established in 2012. Its supporters state that it is a secular polity organized with direct democracy relying on jineology, anarchism, and libertarian socialist ideology. Thus, the idea of the centrality of women’s liberation in human emancipation has been welcome in the century-old Kurdish struggle for self-determination in the Middle East.

The Russian Socialist Revolution

Historically, the Marxist class struggle view of politics has been compromised by class-collaborationist Social Democracy and Stalinism. There are two exceptions, the Russian socialist revolution of 1917 and the Cuban revolution of 1959. I will briefly discuss their contributions to the historical task of women’s liberation.

The February 1917 revolution that toppled the Tsarist autocracy and culminated in the October 1917 socialist revolution was initiated by women workers striking against the privations of World War I on International Working Women’s Day. The provisional government that took power after February 1917 made Russia the first major country to give women the right to vote. The Bolshevik Party that helped lead the socialist revolution included prominent women leaders like Inessa Armand (1874-1920), Alexandra Kollontai (1872-1952), Nadezhda Krupskaya (1869-1939), and Aleksandra Artyukhina (1889 – 1969). Among the first decrees of the Bolshevik government were measures aimed at guaranteeing equality of the sexes and abolishing the centuries-old enslavement of women to their husbands and fathers.

In October 1918, Soviet Russia liberalized divorce and abortion laws, decriminalized homosexuality, permitted cohabitation, and ushered in many reforms that made women more equal to men before the law (Goldman, 1993). In 1919, the Communist Party program included the following to advance women’s rights,

“The task of the party at the present moment is mainly to carry on ideological and educational work for the purpose of finally stamping out all traces of the former inequality and prejudices, especially among the backward strata of the proletariat and the peasantry. Not satisfied with the formal equality of women, the party strives to free women from the material burden of the obsolete domestic economy by replacing this with the house-communes, public dining halls, central laundries, nurseries, etc” (The Communist Party, 1919).

These and many other gains of the working people were lost as the revolution degenerated and the counter-revolutionary Stalinist bureaucratic caste came to power in the 1920s.

The Russian revolution led by the Bolshevik Party was unique. Except for Cuba, all other revolutions whose leaders claimed to pursue socialism were led by Stalinist parties that did not support women’s rights and even suppressed political, democratic, and personal freedoms.

The Cuban Revolution

The Cuban revolution of 1959 was led by the July 26 Movement, a revolutionary current seeking political independence for Cuba and supporting the Cuban working people based on Latin American revolutionary nationalist heritage (Castro Ruz, 1953). Women played a significant role in it, at least 10% of the Rebel Army fighters were women, and some held leadership positions (Klouzal, 2008, p. 97). Several women were involved in the assault on the Moncada Barracks on July 26, 1953, which initiated the uprising against the U.S.-backed Batista dictatorship. It also helped found the July 26 Movement. These women included Haydée Santamaría (1923 – 1980), Vilma Espín (1930 – 2007), Melba Hernández (1921 – 2014), and Celia Sánchez (1920 – 1980), who were leaders of the revolution. In a speech in Havana after the revolution’s victory, Fidel Castro proclaimed: “When a people have men who fight and women who can fight, that people are invincible” (Murray, 1979).

Before the 1959 revolution, women’s social role in Cuba was defied by the patriarchal notions of domesticity, and they had minimal access to educational or professional opportunities. The 1959 revolution provided women with free access to education and professional career opportunities. Universal education, health care, access to child care centers, and the right to safe abortion on demand have worked in combination for Cuban women to live fuller lives.

Unlike the Bolsheviks, however, the July 26 Movement was not trained in socialist theory and history. The Cuban leadership has not encouraged self-organization and self-mobilization of the working people, including women. The Federation of Cuban Women (FMC) was established in 1960 with Vilma Espín as its president and has been closely tied to the Communist Party established in 1965 and the government. Thus, the Cuban leadership has proved insensitive to some non-class forms of hierarchy and oppression.

In the 1960s and 1970s, many homosexuals in Cuba were fired, imprisoned, or sent to “re-education camps” (Arguelles & Rich, 1984; Cuba-Solidarity.org.uk, no date). It took a fight by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) Cubans and their supporters to correct this homophobic policy of the Cuban government rooted. In 2010, the eighty-four-year-old Fidel Castro took some responsibility for these policies (BBC News, 2010). Mariela Castro Espín (born 1962), the director of the Cuban National Center for Sex Education in Havana, the National Commission for Comprehensive Attention to Transsexual People, and an activist for LGBT rights in Cuba, played an important role in helping their mobilization and in public education.

On September 25, 2022, in a referendum, Cubans overwhelmingly voted in favor of a family law legalizing same-sex marriage and same-sex adoption. The new law also promotes equal sharing of domestic rights and responsibilities between men and women (Aljazeera, September 26, 2022).

The Revolution to End All Forms of Oppression and Exploitation

It is a common mistake among socialists that Marx’s concept of socialism is to end the exploitation of the working class. Marx’s lifetime commitment to the working class was because he viewed it as the universal class, the social agency to emancipate humanity as it liberates itself from the system of wage slavery. Marx’s preoccupation has always been human emancipation, emancipation from alienation from nature, and social alienation.

Historically and theoretically, alienation precedes exploitation because to exploit something or someone, it must be first alienated. In his The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884), Engels explains how these three particular forms of alienation emerged in civilization. However, given the state of knowledge at the time, Engels did not and could not discuss the transition from hunter-gatherers to early farmers that replaced ecocentrism of the former with anthropocentrism of the latter as a manifestation of alienation from nature which laid the groundwork for the development of social differentiation and forms of social alienation, including private property, patriarchy, and the State.

Bookchin’s broadening of the analytical attention from the Marxian focus on classes and modes of production to various forms of hierarchy brings into focus non-class forms of alienation, oppression, and exploitation.

Nonetheless, both Marxian and anarchist theories remained anthropocentric in their design as they focused on pathological social relations. Invariably, they abstract from the natural world of which humanity is a part and, without it, cannot exist. Human emancipation, including women’s liberation, cannot be attained unless alienation from nature is also overcome. Human emancipation, including women’s liberation, will require de-alienation from nature by a return to ecocentrism while shedding all traces of anthropocentrism (Nayeri, 2021; 2013). Instead of the Marxian and anarchist theories focusing on social relations, it is necessary to consider the matrix of ecological social relations historically and trans-historically. For 2.5 million years, our ancestors lived as hunter-gatherers with an ecocentric worldview. They saw themselves as inseparable from the rest of nature and considered other species as kin and persons. With the rise of farming about 10,000 years ago, which required systematic domestication of plants and animals and domination and control over nature, a new worldview, anthropocentrism, emerged and systematically replaced ecocentrism. Social alienation, as reflected in social stratification, followed when early farmers turned a sustained economic surplus. The “Women, Life, Liberty” protests require ridding society of anthropocentrism. Thus, women’s liberation, which is correctly seen as vital for a good society in Öcalan’s account itself, will require transcending the anthropocentric industrial capitalist civilization in the direction of Ecocentric Socialism.

Ecocentric Socialism is based on animistic ecological materialism (for comparison with Marx’s and Engels’s historical materialism, see Nayeri, 2021, Table 1). It views the question of agency as the interrelationship of animate and inanimate beings in an ecosystem. Everything in nature, including human society, has agency only in its interconnection and interaction with all others. Everything has an intrinsic value. This view rejects all hierarchies in nature and in society. If liberty and the pursuit of happiness are humanity’s rights, they must also be extended to all others in nature. Thus, human emancipation, women’s liberation, and animal liberation are co-equal and are necessary for each other. No human society will ever be free unless all forms of systematic domination, control, and management of nature are eradicated.

Ecocentric Socialism proposes, among others (Nayeri, 2021, Section 4), four planks: unconditional love for nature and Mother Earth, dismantling all power relations in society and in its relationship with the rest of nature, voluntary simplicity, and a culture of being and loving. “Women, Life, Liberty,” if understood as in Shervin Hajipour’s lyrics based on a random set of protesters’ tweets, suggests an ongoing consideration among the youthful protesters of the same themes. They oppose a society with an authoritarian government saddled with corruption, national chauvinism, poverty, ongoing social repression and stress, homophobia, feral and outcast dogs and cats, and species extinction. They celebrate sisterhood, love, individual and sexual freedom, human rights, and solidarity with Afghan immigrants. In this spirit, the movement should also repudiate all forms of brutality, including against those who have brutalized the people of Iran for 43 years. We must live and act with the values we want to see in the society we want to build as we try to overcome the theocratic anthropocentric capitalist Islamic Republic.

In their power of imagination, courage, self-sacrifice, and defiance, I rest my trust and hope for a revolution to end all oppression and exploitation. •

References

- Alaaldin, Ranj. “Climate change may devastate the Middle East. Here’s how governments should tackle it.” March 14,2022.

- Aljazeera. “Cuba Overwhelmingly Approves Same-Sex Marriage in Referendum.” September 26, 2022.

- Arguelles, Lourdes, and B. Ruby Rich. “Homosexuality, Homophobia, and Revolution: Notes toward an understanding of the Cuban Lesbian and Gay Male Experience, Part I.” 1984.

- BBC. “Fidel Castro Takes Blame for Persecution of Cuban Gays.” August 31, 2010.

- Bookchin, Murray. The Ecology of Freedom: the emergence and dissolution of hierarchy. 1982.

- Castro Ruz, Fidel. “History Will Absolve Me.” 1953.

- Cuba-Solidarity.org.uk. “Gay and Lesbian Rights in Cuba.” No date.

- Düzgün, Mera L. “Jineology: The Kurdish Women’s Movement.” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies. July 2016.

- Engels, Frederick. The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State. 1884.

- Goldman, Wendy Z. Women, the State, and Revolution: Soviet Family Policy and Social Life, 1917-1936. Cambridge University Press. 1993.

- Klouzal, Linda. Women and Rebel Communities in the Cuban Insurgent Movement, 1952–1959. 2008. p. 97.

- Murray, Nicola. “Socialism and Feminism: Women and the Cuban Revolution, Part I.” Feminist Review (2): 57-73. 1979.

- Ocalan, Abdullah. “Democratic Modernity: Era of Woman’s Revolution.” In Liberating Life: Woman’s Revolution. Neuss: International Initiative Edition with Mesopotamian Publishers. 2013.

- The Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Political Program, 1919.

- Murray, Nicola. “Socialism and Feminism: Women and the Cuban Revolution, Part I.” Feminist Review (2): 57–73. 1979.

- Klouzal, Linda. Women and Rebel Communities in the Cuban Insurgent Movement, 1952–1959. 2008. p. 97.

- Nayeri, Kamran, and Alireza Nassab. The Rise and Fall of the 1979 Iranian Revolution: Its Lessons for Today. 2006.

- —————. “Economics, Socialism, and Ecology: A Critical Outline, Part 2,” 2013

- —————. “The Case for Ecocentric Socialism.” 2021.

- —————. “Socialism in the 21st Century: Why It Is Needed and Some of Its Salient Features.” 2022.

- Peña, Susana. “‘Obvious Gays’ and the State Gaze: Cuban Gay Visibility and U.S. Immigration Policy during the 1980 Mariel Boatlift.” Journal of the History of Sexuality, Volume 16, Number 3, July 2007, pp. 482–514.

This article first published on the For Human Liberation website.