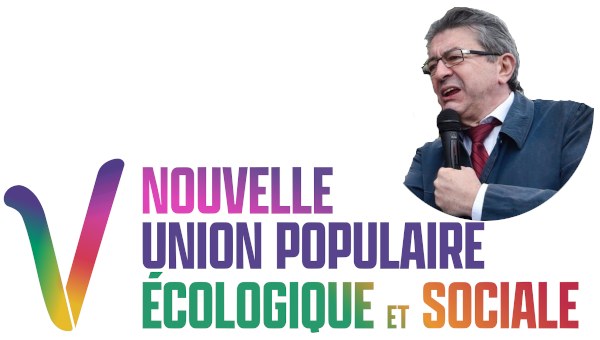

Can Mélenchon’s Left Coalition Defeat Macron in June?

Jean-Luc Mélenchon was beaming at the launch of NUPES (early May), his new electoral coalition, the New Popular, Ecological and Social Union. The former Socialist Party (PS) minister, who split 14 years ago to set up his own movement, was now the undisputed leader of the left and progressive forces in France. His third attempt to reach the runoff for president had just failed by a few hundred thousand votes. Those competitors on the Left and the ecologists had underestimated him. They had criticised his international politics, his anti-Europeanism and the lack of internal democracy in his movement. Now they were standing in the second row.

None of them had even reached the 5% threshold needed to get back their presidential electoral expenses from the state. The Communist Party (PCF), the Socialist Party (PS) and the Greens risked not getting enough MPs for a parliamentary group. Their very survival as significant national political currents was in question. They mistakenly thought the 70-year-old and his movement would at best repeat his previous failure. Early polls seemed to back their view but the ‘tortoise’ steadily progressed and picked up tactical voters from their parties and new voters to do better than ever before (21.95% in the first round).

Mélenchon and his LFI (La France Insoumise/France Unbowed) had dropped some of the worse national populist rhetoric of his 2017 campaign and reached out to win the youth and multi-ethnic vote from the suburbs and poorer housing estates. He had come out clearly against Islamophobia and criticised the police, unlike the moderate left. His post-defeat strategy was also quite different this time.

Mélenchon for Prime Minister

As soon as he failed to get to run off against Macron he switched the focus to the ‘third round’ – the parliamentary elections that follow on from the Presidential contest. He correctly saw the new campaign as a way of blocking Macron’s anti-working class programme by winning a left/progressive majority in parliament. Characteristically he reduced this to the formula – Mélenchon for Prime Minister. The posters were already being printed. With one bound he ditched all his dismissal of the ‘alphabet soup’ of people on the left calling for unity. He had not engaged with the grassroots, people’s referendum movement for a left unity candidate. Now he was François Mitterand reborn. More and more he spoke favourably of the two-term PS president who ended the long years of conservative domination in 1981. Some reforms were made but his presidency soon adapted seamlessly to the needs of French capital.

So the second leg of this ‘third round’ strategy was to rebuild a Mitterand style ‘union of the left’. This was not done in 2017 despite dominating the left vote. He thought he could establish his movement as a big force in parliament but all the left forces ended up with smallish groups and little influence in parliament. This time Mélenchon’s negotiating team of thirty year olds moved quickly to bring the other left forces on board.

At the start, some of the LFI leaders were bullish enough to exclude the ‘social liberal’ PS. They were relishing the moment and rejecting the politics of Francois Hollande and the last PS presidency. Mathilde Panot, chair of the LFI parliamentary group baldly stated “No discussion, it is a definite refusal” – Journal de Dimanche, 16 April. The inclusion of the revolutionary Marxists of the Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste (New Anti-Capitalist Party) was also aired widely – Poutou in Parliament was the cry. The NPA responded positively and negotiations started.

The PS Comes On Board

The exclusion of the PS did not last long. Despite the derisory score in the Presidential race – barely more than the revolutionary candidates – the PS still has a historic base and institutional representation in many places. In the beginning, the LFI position was that the agreement would allocate winnable seats on a basis roughly equivalent to the presidential results. The PS, PCF and the Greens all argued – with a degree of logic – that tactical voting toward Mélenchon distorted this proportionality. Both the Greens and the PS had done much better than their presidential score in the regional and local elections. For example, the Greens captured a number of key cities. All three currents also have sitting MPs with varying degrees of local support. In the end, the LFI were remarkably generous in its allocation of seats. Sitting MPs were largely protected and the PS was given 80 slots. Evidently, the LFI have the clear majority of winnable seats. Mélenchon’s presidential vote meant that he is leading in 104 constituencies, second in more than 200, and could get to the second round in more than 400. You need 289 seats for a parliamentary majority.

Of course, there was a political aspect to the negotiation – and agreement on the manifesto although predictably this generated a lot less heat than the horse-trading on the allocation of seats. Here there were some modifications around the LFI position of ‘disobeying’ EU directives and the new formulation adopted is ambiguous enough to satisfy the Greens and the PS. There has also been some slippage on retirement at full rate at 60 and on immediately increasing the minimum wage to 1,400 euros. However, the PS and EELV were prepared to accept a platform that is significantly to their left – their main concern was to save their MPs and keep their parties afloat. Down the road, they can always break with those positions if necessary.

Historically in France, there have only been a few examples of such united left coalitions. We had the Front populaire (Popular Front) in 1936, the Union de la Gauche with Mitterand in 1981 and the Gauche Plurielle with the Jospin premiership in 1997. The NUPES one today is not dominated by the PS and is anchored much more firmly to a left social-democratic programme which – like the Corbyn project in Britain – is not really acceptable to capitalist interests. Any attempt to fully implement such a programme would produce a big political crisis.

Within the PS there have been resignations and much rumbling from the so-called ‘elephants’ (big beasts) like Hollande, Cazeneuve or Delga. The latter will maintain her candidature in the South West while Cazeneuve has torn up his membership card. There will be a number of places where you will have such people competing with the NUPES coalition. Clearly, there is an ongoing split of the more right-wing social democrats that goes alongside the drain of these people to Macron over the last 5 years. Daniel Cohn-Bendt and other Green MEPs have roundly denounced the agreement because of the LFI’s line on Putin and international questions.

Can Mélenchon Become Prime Minister?

If he does, it will be the first time (in recent years) it has been done. The president-elect always receives an endorsement in subsequent parliamentary elections. Only about 50% of the electorate normally votes in these elections. Unfortunately, those least likely to vote are precisely the new voters that the LFI was able to mobilise. Consequently, a key part of the NUPES strategy is to build up this election, to mobilise and excite left voters and new people. One way of doing this is to make a direct link between Macron’s attacks on social rights like the state pension and the vote this time. Give us a blocking majority and we can stop the increase in the retirement age or we can pass legislation increasing the minimum range. Defending democratic rights against Macron’s repressive laws is another potentially popular issue.

Another problem for the left will the nature of the two-round system. You must win 12.5% of the electoral roll – not of those voting – so it is not easy to make it to the second round. There tend to be a lot of run-offs between two candidates. Macron’s vote will be spread quite well nationally which means his candidates will be in most of the runoffs. Then you could well have the same dynamic as we saw in the presidential elections with the progressive voters backing the Macron candidate if the opponent is far-right or right and conversely if the runoff is against a NUPES representative the moderate right and right could well block with the neoliberal centre to stop the left.

Clearly, Macron will be shifting his tactic somewhat to making the ‘red’ threat of Mélenchon and NUPES, a bigger danger just as he rallied moderate and progressive voters to stop the far-right threat of Le Pen in the presidential elections.

There is some hope for a better result for the left this time. Macron has a five-year record he has to defend. He won the Presidency with less than 50% of the electorate if you take into account abstention, spoilt ballots and people voting for him in the second round to stop Le Pen. He is a lot less popular than last time – his overall vote was nearly ten points less. He may have reached a limit attracting PS voters and has been seen to be tacking more votes to his right than to his left. It is harder this time to make credible openings to these voters.

Another advantage this time is that there is a bigger gap between the presidential vote and the parliamentary elections. This gives the NUPES coalition more time to build a campaign. There is also a good chance that many of the activists mobilised in recent weeks will stick with the movement and help to mobilise the vote. Voting in the poorer, ethnic minority suburbs and estates was greater than before.

If the left were to win a majority it would be different from previous ‘cohabitations’ with different parties in the presidency (Élysée) and leading parliament (Matignon). The difference is much sharper. Just take the left’s proposals for constitutional change – the idea of a Sixth Republic. There are lots of ways a president can counter-attack, using his/her considerable constitutional powers such as dissolving parliament, calling a referendum or even resigning and sparking new elections.

Mélenchon has tried to tone done some of his rhetoric in order to forestall talk of crisis and catastrophe. For example, he has already said that France should speak with a single voice on international questions. He seems to be dipping away from confrontation on Europe too. Does he have more chance of becoming Prime Minister by moving toward the centre or by maintaining the radical dynamic of his presidential campaign? The latest polls (3 May) give NUPES 34% against 24% for Macron, 20% for Le Pen, 8% for the traditional right (the Republicans) and 5% for Zemmour (fascist). Such an encouraging poll does not mean however that a majority is just within the left’s grasp. It will still be a major upset and most commentators discount it happening.

Anti-Capitalists of the NPA Froze Out of Coalition

Despite taking a very positive approach to the negotiations and having a number of meetings with the LFI the Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste (NPA or New Anti-Capitalist Party) will not be part of NUPES.

The initial talk of some sort of proportionality between the various currents did not operate in practice. The NPA was quite happy to campaign under a common banner, to support the manifesto and build the movement everywhere it could. It did not share the rather sectarian and abstentionist position of the Lutte Ouvrière (Workers Fight) revolutionary current which was never interested in a united left platform. However, when it came down to the nitty-gritty of seat allocation the NPA were offered five seats, none of which were winnable. Since the NPA have Poutou, who stood as a presidential candidate this time and Olivier Besancenot who has stood previously, both of whom are workers and are well known national figures, it seems unreasonable not to be assigned one winnable seat. The NPA has suggested that once the turn to the PS was made more strongly the LFI was less interested in integrating forces to its left.

Another point that the NPA was very keen on was the role of local committees in taking a lead in supporting the candidates and organising the campaign. These structures could involve all the currents within NUPES in mobilising new forces to get involved in the campaign. This whole aspect has been toned down in favour of more top-down arrangements between the different currents.

Nevertheless, the NPA does understand that despite this brush off the dynamic of the campaign in terms of encouraging present and future struggles should be welcomed. The NPA will not be standing candidates against NUPES representatives it considers favour a struggle dynamic. Locally it will support such candidates. Where the NUPES candidate represents continuity with the social liberal politics of the PS then the NPA will stand candidates alone or in coalition with other radical forces.

Whatever the outcome of these elections the ‘fourth’ round of struggles in the streets, communities and workplaces will be decisive in stopping Macron’s anti-working class neoliberal policies. •

This article first published on the Anti*Capitalist Resistance website.