France: Voices from Below

In the political sequence opened by the social movement against the French government’s pension reform (setting the legal retirement age at 64 years instead of 62), official discourse has been constantly commented on, analyzed, and relayed. Attention given to discourses from below has been much weaker in comparison, even if the social movement made it possible to free the voices of workers, a rare and important political fact.

The following lines are intended to be a modest contribution to the analysis and safeguarding of these voices from below, which form a “discursive event” (M. Foucault), and risk going unnoticed due to insufficient exposure. These utterances from below are constantly confronted with the “tremendous condescension of posterity” (E. P. Thompson) and of the dominant classes; anonymous, fragile, and ephemeral words, they present potentialities that are linked with the struggles for emancipation. These potentialities will be analyzed here around three key points, using a sample of thirty slogans collected in the movement’s demonstrations.

Autonomous Subjects

The slogans that resounded in the demonstrations of the last six months show the assertion of a collective political subject in response to the project of authoritarian neoliberalism.

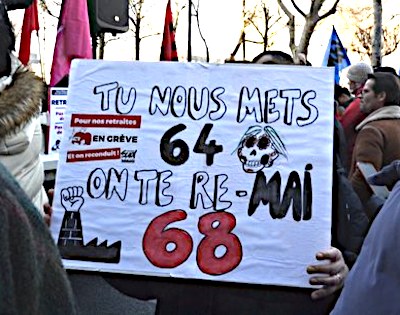

This is what is indicated by the pronouns “on” (we, indefinite form) and “nous” (we), which constantly show up in the slogans shouted and on the placards of the demonstrators, including the following: “If you put us at sixty-four/We’ll re-May sixty-eight/If you put us at sixty-four/We’ll re-May sixty-eight” (See sample below, #4); “The pensions – they are ours/We fought to win them/We will fight to keep them” (#5); “We want to live/Not die at work” (#11).

The indefinite pronoun coming from the Latin homo (man) “on” is used here as a subject, representing an indeterminate collective. At the same time, however, it shares all the attributes of a collective “nous” (we). The French dictionary Le Nouveau Petit Robert indicates among the different uses of the pronoun “on” that its “familiar” meaning refers to “nous.” Unlike the latter, however, “on” marks an indeterminacy capable of leaving open the semantic and social borders of the social movement to the greatest number, in line with its goal of rallying an increasingly mass movement. It is the generic “on,” which refers to “people in general, person” according to this dictionary.

Who are the protagonists to whom these pronouns refer?

The meaning of words depends on their context of enunciation. The semantics of these pronouns, therefore, imply situating them in the middle of processions of trade unions, their flags, their colors, their posters, their lexicon, etc. Seen from this angle, the “on” and the “nous” of the slogans listed below designate the movement of workers in all their diversity but forming a common world, conscious of itself: hospital workers, SNCF railway workers, Enedis electricians, teachers, territorial agents, Social Security employees, students, retirees, postal workers, researchers, mobilized citizens. A clear class character stems from this movement against the government of the upper classes embodied by the “president of the rich” (Emmanuel Macron).

Like the other social movements that preceded this one, the current social movement is in the process of reloading with hope and affect words and symbols whose meaning had become blurred at the end of the short 20th century. To the insensitivity and cynicism of the dominant classes, the social movement opposes a “sensitive reason” (Sophie Wahnich) that is based on the life experiences of ordinary and anonymous people. Daniel Bensaïd explained in 1991 that the lexicon of emancipation struggles had been corrupted by the tragedies and failures of the 20th century revolutions, and that it was necessary once again to tackle the task of patiently constructing a new political lexicon of emancipation: “It is not a problem of a dictionary. A vocabulary is the product of great collective experiences, of founding events.” (Daniel Bensaïd, Penser agir, Paris, Lignes, 2008, p. 39). It is impossible to anticipate the future effects of the current event, but like the 1995 movement, it is now certain that it will be one of the landmark events in social history.

Languages

The slogans of the current movement raise a second issue, that of the “language” mobilized by its protagonists, their historical references, their symbols, and their “dress.”

Marx writes about this in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852): “Thus Luther put on the mask of the Apostle Paul, the Revolution of 1789-1814 draped itself alternately in the guise of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, and the Revolution of 1848 knew nothing better to do than to parody, now 1789, now the revolutionary tradition of 1793-95. (…) Thus the awakening of the dead in those revolutions served the purpose of glorifying the new struggles, not of parodying the old; of magnifying the given task in the imagination, not recoiling from its solution in reality; of finding once more the spirit of revolution, not making its ghost walk again.”

To magnify the struggle, give itself courage, and nourish the imagination with critical resources, the current social movement draws on three different political repertoires that are more or less intertwined: the French Revolution, the workers’ movement, and May 68. If the referents from May 68 and the labor movement appear in the usual repertoire of social movements, those resulting from the French Revolution are generally less present. Looking at the sample of statements above, it appears that Emmanuel Macron’s vertical and solitary exercise of power leads to the adoption of symbolic referents from the royal tradition to denounce him and reveal the “democratic” vacuity of the government. Against all expectations, the demonstrators are therefore unconsciously mobilizing the republican-revolutionary tradition (that of Saint-Just and Robespierre) against a government that uses and abuses the republican-reactionary discourse (of the “party of order” of Adolphe Thiers).

However, recourse to the lexicon and symbols of the French Revolution can only be understood in the figurative sense, without being charged with an immediately comprehensible concrete meaning. For example, what does “All at the Bastille!” mean (#21) shouted by a protester in 2023? What do all these symbols of revolutionary violence mean, such as the reference to regicide or the guillotine? Everything seems to show that these are different forms of symbolic violence, contained and controlled, that the social movement displays to the ruling class as an ultimate warning, suggesting that if the popular will continues to be despised and ignored, then this restrained violence will no longer be contained.

Since no one among the demonstrators is seriously thinking of using any guillotine, for instance, these referents taken from the French Revolution are experienced as out of date and inactual, that is to say uncontemporary. However, the flood of dumbfounded comments aroused in the mainstream media by the slogan “Louis XVI, Louis XVI, we beheaded him, Macron, Macron, we can start again” (Le Monde, April 23) is enough to objectivize the fact that the warning addressed to the ruling class was clearly received by its addressee, even if it was not understood.

Contrary to this restrained violence of social movement, the dominant media discourse stages “the rise of violence” by showing viewers trash cans burning, improvised barricades, and clashes with the police. These images that loop over the news channels saturate the public space and replace the images of the social movement that prove the latter’s legitimacy. Similarly, contrary to the symbolic violence of the social movement, the government has made use of increasingly brutal and arbitrary police repression, using weapons against demonstrators, arousing complaints and criticism from the Defender of Rights and international bodies concerned about human rights in France.

Historicity

Finally, the social movement against the pension reform builds a regime of historicity that breaks with the dominant presentism.

According to the conceptual framework built by François Hartog, a regime of historicity designates the way of articulating the three dimensions of historical time: past, present, future. One of Hartog’s theses maintains that towards the end of the 20th century, we entered a regime of “presentist” historicity in which the present dominates and annexes the other two dimensions of historical time (past and future). The future is then conceived only as the reproduction of an eternal present; the past becomes a memory that follows a zapping of commemorations without a future. We therefore understand to what extent such presentism is synonymous with the neoliberal end of history proclaimed following the fall of the Berlin Wall, that is to say to what extent it is linked with the existing order of things.

Breaking with this dominant point of view, the social movement over the past months has produced new regimes of historicity where new horizons of expectation are put forth. For example, this statement (#24), dating from April 15, near Notre-Dame-de-Paris during a visit by Emmanuel Macron, was made by a law student mobilized against the pension reform: “It’s a symbolic day, nothing will happen. But we won’t let go. Because what is at stake is greater than retirement at 62 or 64: dignity and respect for all.” Another example: “We want to live/Not die at work” (#11). Free life as a horizon, rather than compulsory labor. Dignity and respect for all, rather than contempt and social injustice. Like any horizon of expectation, these horizons are vague, but they make it possible to magnetize, to charge, and to orient the present time of mobilization towards an end which gives it meaning, depth. Each one of these utterances in its own way underlines all the possibilities with which the present moment is charged.

Conversely, a number of statements clearly say to what extent we refuse the future promised by liberalism: “NO FUTURE” (#20); “Working until the age of 64, in health, is quite simply impossible” (#23); Dying at work is not an option/(Neither for my parents, nor for me)” [Verso]; “The dictatorship on the move” (#19).

These regimes of historicity from below are also expressed through historical references to pasts that are linked to this horizon of expectation of life, dignity, and justice. For example, this protest song that played constantly in the sound systems of the processions of all unions: “Pension – they are ours / We fought to win them / We will fight to keep them” or “Retirements – at sixty / We fought to win them / We will fight to get them back” (#5).

A large number of the slogans of the demonstrators highlights the strategic importance of the present moment which must not be missed and must be seized, and the importance of maintaining the struggle: “It’s not in the Assembly, it’s not at Matignon / It is not at the Elysée that we will obtain satisfaction / It is through the strike and its renewal” (#3), “And we will go until withdrawal” (#26).

Under the effect of the discursive event of these utterances from below, time is transformed and becomes political. The present and the future are loaded with new possibilities over the days of mobilization exactly where initially fatality of yet another neoliberal counter-reform prevailed. We think politically because we think historically. In the characteristic uncertainty of critical situations, hope and fear nourish each other, call on each other, instead of neutralizing each other, following the analysis of revolutionary uncertainty offered by Sophie Wahnich. The established order, the capitalist world, and its political personnel appear from this angle as a dying entity, a desperately senile modernity, devoid of legitimacy and at bay, faced with a radiant, dignified, and resolute social revolt which is reappropriating revolutionary horizons: “Happiness is a new idea” (Saint-Just).

It is important that the social movement itself, that is to say, its participants, be able to reflect on its own statements because this is an effort of self-representation capable of opening up new political possibilities in the wake of the sequence begun on January 19.

Slogans

The following slogans come, with some exceptions, from demonstrations that took place in Montpellier, south of France. The translation in English is preceded by the original text in French to enable readers to hear the slogans.

- Slogan, demonstration of March 7: “Macron – Borne – Dussopt et Darmanin/Et hop là! À la poubelle!/Macron – Borne – Dussopt et Darmanin/ A la retraite!/Macron – Borne – Dussopt et Darmanin/Au minimum-vieillesse!.” Translation: “Macron – Borne – Dussopt and Darmanin / And hop there! In the trash! / Macron – Borne – Dussopt and Darmanin / Retired! / Macron – Borne – Dussopt and Darmanin / At least-old age!”

- Song, demonstration of March 7: “Tout est à nous, rien est à eux/Tout ce qu’ils ont, ils nous l’ont volé/Egalité de salaires, retraite à 60 ans/Ou alors ça va péter.” Translation: “Everything is ours, nothing is theirs / Everything they have, they stole it from us / Equal pay, retirement at 60 / Or it will blow up.”

- Slogan, demonstration of March 7: “C’est pas à l’Assemblée, c’est pas à Matignon/C’est pas à l’Elysée qu’on obtiendra satisfaction/C’est par la grève et sa reconduction.” Translation: “It’s not at the Assembly, it’s not at Matignon / It’s not at the Elysée that we will obtain satisfaction / It’s through the strike and its renewal.”

- Song, March 7 demonstration: “Si tu nous mets à soixante-quatre/On te re-Mai soixante-huit/Si tu nous mets à soixante-quatre/On te re-Mai soixante-huit.” Translation: “If you put us at sixty-four/We’ll re-May sixty-eight/If you put us at sixty-four/We’ll re-May sixty-eight.”

- Song, demonstration of March 7: “Les retraites – elles sont à nous/On s’est battu·es pour les gagner/On se battra pour les garder.” Ou bien: “Les retraites – à soixante ans/On s’est battu·es pour les gagner/On se battra pour les retrouver.” Translation: “The pensions – they are ours / We fought to win them / We will fight to keep them.” Or: “Retirement – at sixty / We fought to win them / We will fight to find them.”

- Placard in the CGT head procession, demonstration of April 13: “Les prolétaires n’ont rien à perdre que leurs chaînes. Ils ont un monde à gagner. Prolétaires de tous les pays, unissez-vous!” Translation: “The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to gain. Proletarians of all countries, unite!”

- Placard, demonstration on April 13: “L’eau bout à 100°C. Le peuple à 49.3.” Translation: “Water boils at 100°C. The people at 49.3.”

- Placard, April 13 demonstration: “On ne vieillit pas tous comme Brigitte.” Translation: [Caricature] “We don’t all age like Brigitte.”

- Poster, boulevard de Strasbourg, demonstration of April 13: “Achète-toi une dignité/Ramasse un pavé/En marche pour l’Elysée.” Translation: “Buy yourself a dignity/Pick up a cobblestone/On the march for the Elysée.”

- Poster, boulevard de Strasbourg, demonstration of April 13: [Couperet de guillotine. A gauche dans la photo ci-dessous] “La foule se tue à la tâche, l’élite à la coupe.” Translation: [Cutter of the guillotine. On the left in the photo below] “The crowd works itself to death, the elite with the cut.”

- Poster, boulevard de Strasbourg, demonstration of April 13: “Nous voulons vivre/Pas mourir au travail.” Translation: “We want to live/Not die at work.”

- Poster, boulevard de Strasbourg, demonstration of April 13: “Sauve ta retraite/Mange ton actionnaire.” Translation: “Save your pension/Eat your shareholder.”

- Banner of the anti-fascist organization “La Jeune Garde“, demonstration of April 13: “Défends ta retraite/Défends ta classe.” Translation: “Defend your retirement/Defend your class.”

- Placard of a woman demonstrating, April 13: “On a le droit de dire Non.” Translation: “We have the right to say No.”

- Placard with a caricature of Macron as a crowned king: “Sire, On en a gros.” Translation: “Sire, we’re really angry.”

- Slogan of the head CGT procession, demonstration of April 13: “Un pas en avant/Un siècle en arrière/C’est la politique/Du gouvernement.” Translation: “A step forward/A century back/It’s the policy/Of the government.”

- Graffiti made during the demonstration of April 13, near the Saint-Roch station: “Silence la police assassine.” [En rouge]. Translation: “Silence the police kill.” [In red].

- Inscription on a yellow vest worn in a CGT procession, demonstration of April 13: “Ni Dieu/Ni maître/Ni flics/Anticapitaliste.” Translation: “Neither God/Nor master/Nor Cops/Anticapitalist.”

- Protester’s placard, April 13: [recto] “Crever au travail ce n’est pas envisageable/(Ni pour mes parents, ni pour moi).” [Verso] “La dictature en marche.” Translation: [front] “Dying at work is not an option / (Neither for my parents, nor for me).” [rear] “The dictatorship on the move.”

- Placard of a young demonstrator, April 13: “NO FUTURE.”

- Outside the courthouse on April 13, as he takes a photo of the processions behind him, a CGT activist wearing the chasuble of the Lodève-Clermont trade union section shouts: “Tous à la Bastille!” Translation: “All to the Bastille!”

- Demonstration of January 19, Lyon. Giovanni Pieredda, 50, social worker, answers to questions of Le Monde journalist (April 14 edition): “Quand je vois mes collègues âgés, c’est vraiment pas bien de leur faire ça.” Translation: “When I see my elderly colleagues, it’s really not good to do that to them.”

- Demonstration of January 19, Amiens. Marie, 52, hospital worker, answers to questions of Le Monde journalist (April 14 edition): “Bosser jusqu’à 64 ans, dans la santé, c’est tout simplement impossible.” Translation: “Working until the age of 64, in health care, is simply impossible.”

- Saturday April 15, near Notre-Dame-de-Paris during Emmanuel Macron’s trip. Johann, a law student and mobilized against the pension reform, pushed back to the other side of the Seine by the police, answers to questions of Le Monde (April 16-17): “C’est une journée symbolique, il ne se passera rien. Mais on ne lâchera pas. Car l’enjeu est plus grand qu’une retraite à 62 ou 64 ans: de la dignité et du respect pour tous.” Translation: “It’s a symbolic day, nothing will happen. But we won’t let go. Because what is at stake is greater than a retirement at 62 or 64: dignity and respect for all.”

- Friday April 14, forecourt of the Hôtel de Ville in Paris, after the official opinion delivered by the Constitutional Council. Younis, masseur, 30 years old: “Quelle peut être la solution d’un peuple qui se sent abandonné par l’ensemble de ses institutions? Ce soir, tout ça me fait peur.” Translation: “What can be the solution for a people who feel abandoned by all of their institutions? Tonight, all that scares me.” (Le Monde, April 16-17).

- Friday April 14, forecourt of the Hôtel de Ville in Paris, after the official opinion delivered by the Constitutional Council. Slogans sung at the microphone by union activists: “Et on ira jusqu’au retrait” – “Constitutionnelle ou pas, cette loi on n’en veut pas.” Translation: “And we will go until the withdrawal” – “Constitutional or not, this law we do not want it.” (Le Monde, April 16-17).

- Friday April 14, forecourt of the Hôtel de Ville in Paris, after the official opinion delivered by the Constitutional Council. Pierre François, storekeeper, in his fifties. “C’est tout? Il ne se passe plus rien? Personne ne se révolte après ça? Mais je pensais que les gens réagiraient plus, que ça partirait vite en manifestation sauvage. Les autres n’y croyaient donc pas plus que moi. Mais je voulais qu’on vive ça ensemble. Ce n’est pas rien quand même ce qu’on a traversé toutes ces semaines.” Translation: “Is that all? Nothing is happening anymore? Nobody is revolting after that? But I thought that people would react more, that it would quickly go into a wild demonstration. So the others didn’t believe it any more than I did. But I wanted us to live this together. It’s not nothing after all what we’ve been through all these weeks.” (Le Monde, April 16-17).

- Demonstration of April 23, Paris: “Louis XVI, Louis XVI, on l’a décapité, Macron, Macron, on peut recommencer.” Translation: “Louis XVI, Louis XVI, we beheaded him, Macron, Macron, we can start again.” (Le Monde, April 23).

- Demonstration of April 23, Paris: “Macron, si tu te prends pour un roi, la guillotine t’attendra.” Translation: “Macron, if you think you are a king, the guillotine will be waiting for you.” (Le Monde, March 23).

- Placard in the shape of an arrow, Paris, April 23: “Baden-Baden/49.3 bornes/(Itinéraire conseillé).” Translation: “Baden-Baden/49.3 terminals/(Advised itinerary).” (Le Monde, April 23). •

This article first published in French on the Mediapart blog.