Haiti: From Neo-Colonialism to Neoliberal Brutality

The 1697 Treaty of Ryswick legalized French control over the western third of the island of Hispaniola – a Spanish asset – under the name of Saint-Domingue. The colony proved to be a valuable spigot of wealth. In 1789, Saint-Domingue supplied two-thirds of the overseas trade of France and was the greatest individual market for the European slave trade. It was a greater source of income for its owners than the whole of Britain’s thirteen North American colonies combined. The labour of half-a-million slaves propped up the dazzling opulence of the French commercial bourgeoisie, and formed the hidden foundations of cities like Bordeaux, Nantes, and Marseille. In August 1791, after two years of the French Revolution and its ripple effects in Saint-Domingue, the slaves revolted.

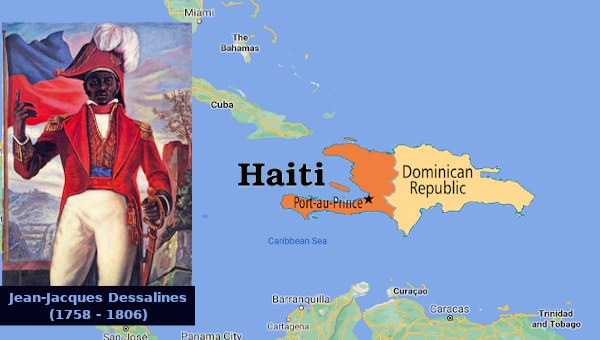

Collective British, Spanish, and French efforts to crush the rebellion set off a war that lasted thirteen years and concluded with the humiliating defeat of imperial powers. William Pitt the Younger and Napoleon Bonaparte together lost some 50,000 troops in the campaign to restore slavery and the arrangements of exploitation. The defeat of the latter’s expedition in 1803 resulted in the establishment of the state of Haiti. On January 1, 1804, General Jean-Jacques Dessalines declared Haiti an independent country:

“Citizens, it is not enough to have expelled the barbarians who have bloodied our land for two centuries; it is not enough to have restrained those ever-evolving factions that one after another mocked the specter of liberty that France dangled before you. We must, with one last act of national authority, forever assure the empire of liberty in the country of our birth; we must take any hope of re-enslaving us away from the inhuman government that for so long kept us in the most humiliating torpor. In the end we must live independent or die.”

Revolution and External Pressures

Dessalines was a former slave who had risen through the ranks of the army during the Haitian Revolution and become one of the leaders of the struggle against the French after the deportation of General Toussaint Louverture, his predecessor. Written as a message from him to the nation, the Declaration laid out the Haitians’ grievances against France and proclaimed the determination of the Haitian people to resist the return of slavery and colonialism. It is believed that the document was drafted by Louis Boisrond-Tonnerre, one of Dessalines’s secretaries, who had said that the declaration “should be written with the skin of a white man for a parchment, his skull for a desk, his blood for ink, and a bayonet for a pen.”

Haiti’s independence was not a smooth process. Imperialist countries intervened incessantly to block any path for the continued advancement of national liberation. After the defeat of France’s Napoleonic forces, a French general named Jean-Louis Ferrand established a government in Santo Domingo (present-day Dominican Republic), which lasted until Spanish and British militaries ejected the French from the colony in 1809. General Ferrand was an unabashed advocate of slavery, and his regime sought to place back into servitude thousands of men, women, and children who had won their freedom in the French general emancipations of 1793-94. He also authorized slaving raids into Haiti.

The harms inflicted by military raids were amplified by the repercussions of a total embargo. In 1825, Charles X issued a Royal Ordinance recognizing the independence of “the French side of Saint Domingue” under the condition that the Haitian government pay a substantial indemnity to compensate the former plantation owners for property – including human beings – lost during the revolution. The ordinance was accompanied by a French squadron prepared to start a blockade should Haiti not accept the agreement. France, which had already wrung Haiti economically dry, now appeared as the creditor for the slave regime against the Haitian people. Haiti paid the debt at oppressive interest rates for 122 years – until 1947. The indemnity is valued today at $22-billion. The drain of this wealth left Haiti in an enfeebled state.

Internal Divisions

After Dessalines was assassinated in October 1806, there were two strong contenders for power in Haiti: Henri Christophe and Alexandre Petion. The mulatto elites – people of mixed white and black ancestry – created a constituent assembly to form a government. They selected Christophe, a black general, to be president and Petion to head the legislature. The selection of Christophe was an attempt to rule through titular black leaders – a framework known as politique de doublure (policy of lining). However, Christophe had no intention of being a puppet president. He raised an army and marched to Port-au-Prince but could not take the city, which was commanded by Petion, who had powerful artillery.

Christophe went north and captured Cap Haitien. He brought in warriors from Dahoumey in central Africa to serve as his elite guard. In the south, Petion was made president-for-life of the Republic of Haiti with the capital at Port-au-Prince. Haiti remained separated until Christophe’s death in 1820. In 1818, President Jean-Pierre Boyer took power in the north of Haiti and reunited the country two years later. Even as north and south were being fused, another territorial problem emerged. In 1822, as some Dominicans in Santo Domingo began organizing to gain independence from Spain, Boyer joined the eastern part of the island, a former Spanish possession, to the Haitian Republic. The Unification followed a constitutional ideal: merger of the whole island in the face of foreign aggressions.

But by the early 1840s, Dominicans developed animosity for Boyer’s regime. Soon after he was overthrown in 1843 and General Charles Rivière-Hérard took power, a small group of activists in Santo Domingo overturned unified rule in the Dominican capital. Rivière-Hérard tried to oppose the separation and sent troops eastward, but he was more focused on the consolidation of power at home and could not succeed due to domestic instabilities. On February 27, 1844, the Dominican rebels drove the last Haitian troops from the capital, securing independence.

American Occupation, Resistance Movements, and Coups

In 1898, the US extended its imperial tentacles into the Caribbean, expelling the Spanish in the Spanish-American War and occupying Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Puerto Rico. During the period of the US occupation of Haiti, a constitution was written, in 1917, that enabled foreign ownership of Haitian land, which had been prohibited earlier. Widespread resistance against this law was put down by the Haitian Gendarmerie and the National Guard – instruments of repression created by the US Marines to maintain colonial rule. Fifteen to thirty thousand Haitians died in continuous cycles of state violence, though this could not avert a peasant rebellion in 1919-1920 and a string of strikes in 1929. The erosion of America’s direct occupation began in 1930, with the reinstitution of legislative and presidential elections in Haiti, and ended in 1934, with the departure of the US forces on 14 August.

In 1941 – under the presidency of Élie Lescot – the Haitian-American Agricultural Development Company (SHADA) was created with a $5-million grant from the US Export-Import Bank. This megaproject, spanning 100,000 hectares in Haiti, was set up to produce rubber for the Allied countries engaged in World War II. By 1944, the project had failed: productive capacities collapsed, no durable infrastructure was left, and peasants were forcibly displaced from their lands. The economic failures were accompanied by repression and surveillance. A government law was formulated requiring the presence of a police officer at all meetings of workers associations.

In 1946, a popular movement consisting of workers and students mobilized to oust Lescot’s regime. The revolt was led by young Marxists based in Port-au-Prince, the capital of Haiti. These radical energies were soon suppressed by the ruling class. Lescot ordered Colonel Lavaud – the head of the National Guard – to use all necessary force to break up the mobs. The latter refused and was immediately arrested. The second-ranking officer of the National Guard, Colonel Antoine Levelt, talked with Lavaud and US ambassador Wilson to decide the future game plan. Along with the embassy, they formed a Military Executive Council, which obtained Lescot’s resignation once they convinced him his life was in danger if he remained in Haiti a day longer.

Frightened out of their wits, the rest of the cabinet submitted their resignations and took to their heels and escaped from the country. At three o’clock in the morning of January 11, 1946, Lescot and his family – seated in the back of a police car – drove to Bowen Field, then boarded a waiting plane to Miami, becoming Haiti’s first exiled president since the American occupation. Dumarsais Estimé – the succeeding President – initiated a modest programme of reform which incurred the wrath of the American empire. US corporations, namely SHADA and Haitian American Sugar Company (HASCO), labeled Estimé’s administration communist”; US banks denied the government any form of debt relief and new loans. Estimé was finally removed in a coup by the National Guard.

Imperialist Strangulation

Starting in 1950, the US supported the successive dictatorships of François Duvalier (Papa Doc) and his son Jean-Claude (Baby Doc) for more than thirty years. The Duvaliers cemented Haiti’s peripheral location in the global capitalist system. Restiveness among the population – a result of widespread economic distress – was quelled through the use of excessive violence. The Duvalier’s paramilitary – Tonton Macoutes, trained by the US military – killed over 50,000 people. Mass struggle eventually overthrew the dictatorial regime. In 1986, an uprising in Gonaives sparked rural rebellions all over Haiti, which eventually reached the capital. By February of that year, Baby Doc fled to France on a US Air Force jet.

Haiti’s citizenry reentered the international stage with an economic landscape devastated by the Duvaliers. The IMF solution for Haiti’s wretched poverty involved further reductions in wages – which had reached starvation levels – privatization of the state sector, reorientation of domestic production in favour of cash crops popular in North American supermarkets, and the elimination of import tariffs. There was no forgiveness for the large debts accumulated by a dictatorship characterized by a lack of accountability. Attempts to fight these injustices through a sustained movement – known as the flood (lavalas), led by the former priest Jean-Bertrand Aristide – were undermined through external interventions. In September 1991, just seven months after Aristide’s inauguration, the army seized power, installing a new junta under General Cédras.

Over the next three years, the military instituted a reign of terror in an attempt to dismantle the Lavalas networks in the slums; around 5,000 Lavalas supporters were killed. Churches and community organizations were invaded; preachers and leaders were murdered. In April 1994, paramilitaries under the leadership of Jean Tatoune, a CIA thug, slaughtered scores of civilians in the town of Gonaives in what became known as the Raboteau Massacre. Soon, the military regime was facing difficulties in holding together without open and constant massacre, which led to increasingly large numbers of refugees – a political problem for the US. On September 18, 1994, the Americans sent former President Carter, Senator Sam Nunn, and former Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman Colin Powell to Haiti to negotiate Cedras’s removal.

Cédras agreed to leave on October 15, 1994. Aristide had to make a number of compromises for this agreement. He forwent the right to prosecute many human rights violations; he signed away three years of his presidential term, agreeing that his term would end in February 1995, counting the coup years as if he had been president; and he dropped his preference for Prime Minister, leftist Claudette Werleigh, in favour of neoliberal Smarck Michel. These decisions were forced upon Haiti by an international conjuncture containing little room for maneuver. In November 2000, Aristide again won the presidential election with 92% of the votes cast, on a turnout estimated at around 50%.

He tried his best to utilize Haiti’s drastically limited resources for the betterment of the people. During his two terms, the country oversaw the creation of more schools than in all the previous 190 years. It printed millions of literacy booklets and established hundreds of literacy centres, offering classes to more than 300,000 people; between 1990 and 2002 illiteracy fell from 61% to 48%. With Cuban assistance, a new medical school was built in the Port-an-Prince suburb of Tabarre, offering free medical training to students from poor communities who agreed, upon graduation, to contribute their services in Haiti’s poor and rural neighborhoods.

The rate of HIV transmission reduced, with clinics and training programmes opened as part of a public campaign against AIDS. The infant mortality rate decreased through the strengthening of healthcare. Aristide’s government increased tax contributions from the rich and, in 2003, announced the doubling of a highly inadequate minimum wage.

The Lavalas government’s pro-poor policies perturbed the propertied class and its imperialist benefactors. At the request of the US, France, and Canada, the United Nations Stabilization Force in Haiti (MINUSTAH) was dispatched in June 2004. The purported objective was to subdue militant oppositional groups and to work to rebuild local communities and political alliances.

However, a 2017 investigation by the Associated Press showed the UN force as a murderous occupying army. The evidence showed thousands of cases of rape and torture as well as the dissemination of cholera – a disaster for Haiti. The peacekeeping force was incriminated in everything that was against its mandate.

The masses deeply resented the well-funded occupying force, whose $500-million budget could have immensely benefited Haitians during the food riots of 2008. The plight of the Haitian people was exacerbated by the massive earthquake which struck the country in January 2010. More than 300,000 people died in this tragedy.

The IMF used this crisis to increase Haiti’s dependency by granting the country a loan of $114-million. The terms of this loan have continued to asphyxiate Haiti’s sovereignty in the years since. An international recovery effort produced close to $9-billion in aid. However, 59% of the funds went to UN agencies, international NGOs, and private contractors; 40% went to the countries’ military-dominated entities; and only 1% went to the Haitian government. Thus, large chunks of the money that could have gone a long way to helping Haiti recover were frittered away through corruption at all levels, leaving the Haitian people in an ongoing desperate state.

Neo-Colonialism

In 2011, the US-controlled Organization of American States (OAS) collaborated with the Haitian elite to install Michael Martelly as the president. Martelly was a neo-colonial stooge, responsible for eviscerating an already weak Haiti through his “Open for Business” policy. The opening of a South Korean manufacturing plant in Caracol, an area in northeast Haiti unaffected by the earthquake, displaced hundreds of Haitian farmers, confiscating arable land.

The plant was praised for providing 15,000 jobs by the Interim-Haiti Recovery Commission, headed by former US president Bill Clinton. However, the East Asian corporation Sae-A received wide-ranging and unjustified benefits: tax exemptions, duty-free ports, and cheap labor. National impoverishment continued. Martelly stepped down in February 2016, handing power to a provisional president in the aftermath of the 2015 elections, which were marred by fraud. The final round of elections was held weeks after Hurricane Matthew wrecked large parts of the country. Jovenel Moïse, a businessman who was Martelly’s chosen successor, became president in February 2017. Only 20% of Haiti’s voters showed up on the day of election.

In other words, less than 10% of registered voters – only about 600,000 votes – supported Moïse. He started confronting mass opposition in the streets from 2018, when his government raised fuel prices by 38% (gasoline) and 51% (diesel and kerosene) as part of an IMF “readjustment” program. Grassroots resistance intensified as it emerged that some $4-billion in oil import subsidies supplied by Venezuela under its Petrocaribe program, meant for developmental purposes, had been pocketed by Moïse and his cronies. In the bargain, the corrupt Haitian government received Washington’s support in exchange for abetting its regime-change operation against the socialist government of Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro.

As neoliberal brutality led the Haitian masses to take to the streets, Moïse’s rule became authoritarian. Beginning from October 2019, he ruled by decree after dissolving Parliament when elections could not be organized. Haiti’s armed forces were reinstated after having been disbanded in 1995, the powers of the police were bolstered, and a National Intelligence Agency – accountable only to the president – was established. Moïse also proposed a referendum to establish a new constitution, which would have increased the dominance of the president. Proposed changes included abolishing the post of prime minister accountable to the legislature; replacing the bicameral parliament with a unicameral one; and eliminating the prohibition in Haiti’s Constitution on a president serving two consecutive terms. This last measure was introduced as a democratic buffer following the downfall of the Duvalier dictatorship.

Moïse’s presidential term ended on February 7, 2021. Despite repeated calls to step down and mass protests demanding his resignation, he refused to leave office. His administration became an open dictatorship, relying on the deployment of pure force to sustain itself. At 1 a.m. in the morning of July 7, 2021, armed gunmen – two Haitian-Americans and 26 Colombians – stormed Moïse’s private residence in Pétionville, a wealthy suburb of Port-au-Prince, and assassinated him. This killing was the result of Moïse’s aggressive pursuit of personal ambitions and endless efforts to cling to power. His mode of governance ultimately alienated and antagonized many actors in Haiti. •