Remembering Larry Nozaki: ‘Enemy Alien’, Unionist, Socialist

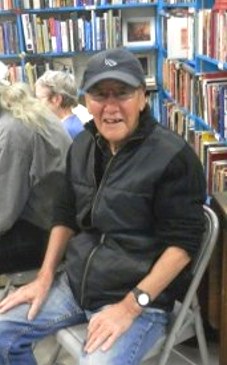

Sadly, Larry Nozaki (1940-2020) died in Surrey BC on December 5, 2020. Larry was a casualty of the anti-Japanese internment camps during the war, long-time union activist in the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW), and a member of the League for Socialist Action (LSA) Vancouver Branch. Below is a photo of Larry, and remembrances by his cousin and others who remember Larry, his life, and his contributions to revolutionary socialism.

- “Governmental Cruelty and the Kindness of a Friend,” by JoAnne Maikawa (Larry’s cousin) and Richard Roman

- “A CUPW Pioneer Leaves Us,” by Evert Hoogers, past president, Vancouver CUPW

- “Mentor, Friend, Working-Class Leader,” by Joan Campana

- “A Life of Militant Spirit and Socialist Conviction,” by John Riddell

— Georgina Cordoba.

Governmental Cruelty and the Kindness of a Friend

JoAnne Maikawa with Richard Roman

My cousin Larry Nozaki died on December 5, 2020, two days shy of the 79th anniversary of Pearl Harbor Day. Born on October 5, 1940, he was 14 months old when declared an “enemy alien” by the government of Canada, along with myself (age 6 ½) and the rest of our family. Our families were soon forced to move into self-internment in the interior of British Columbia, our properties and freedom stolen. The Japanese attack on a US naval base had provided the excuse to act on the long-existing anti-Asian racism rampant on the west coast of North America.

Those families that could arrange and pay for their own internment in the interior were able to avoid the prison camps but were under RCMP supervision. The families of Larry’s father, Mitz, and those of his sister, Kiyo (my mother), and younger brother, Kenji, were able to move to Blind Bay, BC, because of the generosity of an Italian immigrant bowling alley owner for whom Mitz had worked for as a pin boy.

Maryka Omatsu has described this in the Nikkei Voice of February 12, 2018:

“Since the 1920s, when JoAnne’s mom was a teenager, she and her brother Mitz had worked for Frank Panvini, owner of the popular Chapman chain of bowling alleys in Vancouver. There is still an alley on Granville. (It is said that Mitz and Frank invented 5-pin bowling).

“Frank Panvini turned out to be a true friend. On learning of the evacuation order, Frank bought a farm in Blind Bay for the Nozaki and Maikawa families to live in. In 1943, when the Trustee of Enemy Property auctioned off Mitz’s family home in East Vancouver, Frank purchased it for his friend. In 1949, when the War Measures Act lapsed, Mitz had a house to return to. When Frank died he left a bowling alley to Mitz…

“Mitz (bowling alley) Nozaki remained in Blind Bay until 1949, when Japanese Canadians were finally given the rights of Canadian citizenship and could live on the west coast.

“He returned, one of the lucky few, to his pre-war home in Vancouver.”

We lived in primitive conditions in Blind Bay without running water, indoor plumbing or electricity. Larry was a sweet and adorable two-year-old. We would play together, two little “enemy aliens.”

I was there from age 6½ to 8, Larry from 14 months to 9. My family was allowed to move to Toronto in 1945, Larry’s branch of the family, wishing to return to Vancouver, stayed until 1949 as Japanese Canadians, while being allowed to move East under certain conditions after 1945, were not allowed to return to the West Coast until then.

Larry visited Toronto occasionally where he would attend meetings at the back of a bookstore on Queen Street near Spadina, which unbeknownst to me, was the meeting place of the Trotskyists.

I have shared some of my memories of removal from Vancouver and living in Blind Bay at a conference at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre in Toronto. •

A CUPW Pioneer Leaves Us

Evert Hoogers

I have just received the news that Brother Larry Nozaki, who was an active participant in the “illegal” postal strike of 1965 from which emerged both postal unions, as well as a long-time Local Executive member and shop-floor leader in CUPW, has died. His passing brings back many memories of our work together in the Vancouver Local of CUPW. Here is some of what I would explain to younger postal workers about how I remember him.

Larry became an inside postal worker just in time to become immersed in the 1960s explosion of working-class struggle in this country – the most important for several decades – and the first major expression of the determination of public sector workers that militant trade unionism would represent their future. Larry immediately began participating in the Vancouver postal workers organizing work. This meant, since Montreal and Vancouver (both inside workers and outside letter carriers) were effectively leading this fight for union recognition, that Larry would play a crucial role.

Larry’s role in organizing the 1965 strike, and his continuing leadership in the CUPW Vancouver Local was recognized in Michael Ostroff’s labour documentary Memory and Muscle, featuring Larry commenting on what an amazing difference of attitude on the work floor became obvious after the strike – because it revealed that workers banding together in solidarity could really win important things.

I started work at Canada Post in 1972, and, as luck would have it, I was assigned to the same general work section as Larry, who was already a senior Local union executive officer and Shop Steward. To some degree, I knew Larry prior to this from his political work in the League for Socialist Action, as a result of my own developing commitment to a socialist understanding of the world. But It will come as no surprise to trade union activists that you really get to know your union Brothers and Sisters when you deal with them day-to-day, resisting employer attacks and representing your fellow members. And so it was with Larry. It was as a result of this solidarity relationship that I learned of Larry’s childhood in the WWII Japanese internment camp at Blind Bay in 1940, with all the racism and collective hardship it implied. Larry’s family was unable to return to Vancouver until 1949. Since my family lived in the 1960s in Greenwood, BC where a similar interment camp had been established in the war years, I was able to gain a little insight into what Larry had gone through.

Larry became a significant mentor to me as I learned what it meant to be a shop-floor organizer and representative. He taught me the basics of work-floor “mapping” and what to expect – and who to expect it from – in the daily to and fro with supervisors, superintendents and other managers whose purpose in life appeared to focus on doing an end-run around our collective agreements. Importantly, he also provided leadership in analyzing the internal union political struggles that characterized CUPW National and Local life. He remained on the Local executive and was a delegate to many Conferences and Conventions for a number of years. I especially remember the way he was able to bring his experience to bear so effectively in the Vancouver Local Strike Committee during the many tense moments of the 1978 CUPW strike where postal workers defied back-to-work legislation by Trudeau the Elder, and in the 1981 strike where CUPW won the break-through victory of paid maternity leave.

I was reminded of this reading Joan Campana’s memory of Larry’s “frequent admonitions and succinct homilies,” including his oft-quoted reminder that we need to always be prepared for a long struggle. On a lighter note, we could without fail be assured at least once during any union discussion of a collective agreement offer by the boss that “it’s nothing more than a dog’s breakfast!” and that if the union foolishly accepted it “then we’re really up Shit Creek!”

Larry Nozaki was a friend, a mentor, a union Brother and a comrade. His work as a trade unionist and socialist to build a better world has provided an important contribution to the continuing struggle. •

Larry Nozaki, Mentor, Friend, Working-Class Leader

Joan Campana

I met Larry in 1968 in a large meeting hall behind the Vanguard Bookstore at 1208 Granville Street in downtown Vancouver. The heart of the building, just alongside the meeting hall, was another sizable room, a kitchen always bursting with noise and people coming and going. Sometimes to the office of the Young Socialists tucked away in the back there. Mostly to the kitchen itself, with its tradition of not-to-be-missed communal dinners that preceded the Friday-night forums. We learned as much from the animated discussions at the long tables as we did from the meetings themselves.

Larry never missed a dinner or a forum. He was short, with vigorous jet-black hair and the most alert, lively black eyes. I remember him sauntering into the kitchen. He had a unique walk, slow, with a relaxed gait, hands in his pockets. A small smile would often become a deep chuckle, then a huge laugh. His body radiated the happiness he felt at the growing numbers of young people who were coming around and joining the Young Socialists in the late 1960s.

Larry became a mentor of mine. I didn’t have a car, and he often drove me and other young YS’ers home from late meetings at the hall. It was in the days of large cars, and he always drove a very large one. We once had four of us in the front seat.

I learned about the exploitation of working people from Larry’s riveting tales of work and struggle in the Vancouver post office. He was an inside worker who not only participated but played a leading role in the wildcat strikes of 1965 that formed the Canadian Union of Postal Workers, CUPW. He was a picket captain and leader in subsequent strikes, the one I personally remember in 1968, just after I and my companion joined the Vancouver Young Socialists. CUPW played an important role in rejuvenating the labour movement in the 1960s, and it was militant workers like Larry who made that possible.

From Larry I also received some early, indelible lessons about the racial discrimination that pervades Canadian society, and specifically about the internment of Japanese Canadians during World War 2. Larry, along with his family, was one of those rounded up and interned.

I also well remember Larry’s frequent admonitions or succinct homilies. My favorite was: “You’ve got to pace yourself, comrade. It’s a long struggle.” And then he’d chuckle.

I left Vancouver and didn’t return until decades later. A few years after that, Larry and I resumed our friendship. He lived not far from us, we visited and went on the occasional walk. He told me how proud he was that the Canadian Union of Postal Workers had made him a member for life. And told me that if I walked every day I would live a long life. He started almost every morning by walking about 20 blocks from his condo to a local restaurant to read their free daily newspaper and have his breakfast. •

A Life of Militant Spirit and Socialist Conviction

John Riddell

A lifelong labour activist and socialist, Larry Nozaki died in Vancouver on December 5, 2020.

Born to a West Coast family of Japanese ancestry, Larry endured as a young child the Canadian government’s cruel internment in 1942 of most of its ethnic Japanese citizens. Larry retained memories of the harsh conditions endured by his family. His father, a prosperous Vancouver proprietor of movie theatres, suffered the confiscation without cause of his properties.

On leaving school, Larry took a job in the postal service, where he worked until retirement. He quickly became active in the Vancouver postal union, which later merged into the militant Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW).

In 1959, Larry made contact with the Socialist Information Centre, a small Marxist group that held occasional public meetings on Hastings Street, near his home. The Centre’s leading members were Ruth and Reg Bullock, who became Larry’s lifelong friends.

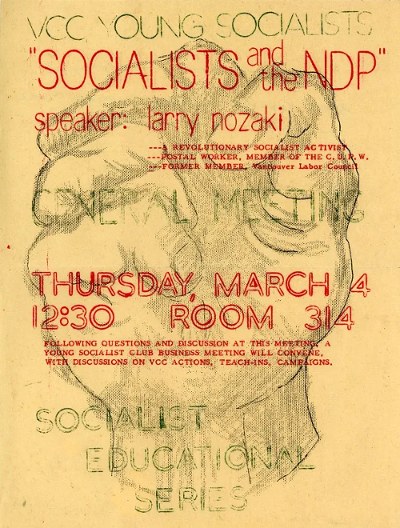

The Socialist Information Centre was loosely linked with a similar group in Toronto led by Ross Dowson and with the Trotskyist Fourth International. In 1961, the two groups in Canada established the League for Socialist Action (LSA). Larry was among the first of a significant wave of young activists that joined the LSA in Vancouver.

The Vancouver LSA launched a bookstore, headed by Ruth Bullock, and carried out intensive education on political themes. Larry joined its members in defending revolutionary Cuba and in building the West Coast wing of the Fair Play for Cuba committee in Canada.

Through his union, Larry was linked to the most radical wing of the labour movement in English Canada. His union local supported the Fair Play for Cuba committee, participated in the movement against the Vietnam war, and defended Quebec during the 1970 War Measures Act.

Larry took part in the 1977 socialist fusion that created the Revolutionary Workers League (RWL), which briefly rallied several hundred members. The RWL then fell into decline and suffered several splits. In about 1983, Larry joined the Bullocks and some other RWL members in breaking away in order to maintain their alignment with the politics of the Fourth International.

The RWL’s breakup was a setback for Larry. He was no longer part of an organized socialist group in Vancouver. Nonetheless, he maintained ties with a group of Fourth International supporters in the United States and, for many years, assisted them with donations.

I met Larry again during his visit with Toronto relatives in 2018. Age had left its mark, but Larry had preserved unchanged his militant spirit and socialist convictions.

Larry Nozaki, presente! •