The GM Lands: Renaissance or Ongoing Catastrophe?

Since 2010, the site of the former GM components plant on Ontario Street in St. Catharines has sat idle. The facility that once employed thousands was sold in 2014 to Bayshore Groups, a private land remediation company that later announced a $250-million redevelopment plan. But after having scrapped the plant and sold its parts, Bayshore ditched the redevelopment. Now, nothing but an empty shell and a pile of rubble remains on the site.

Concerned about the site’s environmental and safety hazards, a Coalition for a Better St. Catharines formed to pressure the city of St. Catharines to clean up the former GM lands. In light of recent reports of high-levels of PCBs in the Twelve Mile Creek adjacent to the property, the Coalition is seeking to hire an environmental consultant to further review the potential that contaminants are leaking off the site. Donations can be made on the Coalition’s action network page.

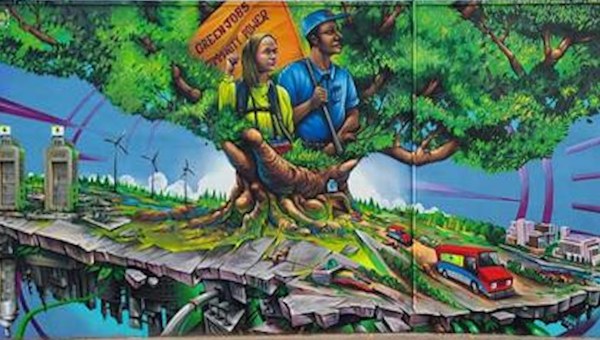

The story of the Ontario Street site underscores Green Jobs Oshawa’s urgent calls for public investment in green, socially beneficial manufacturing.

For a hundred years, the factory on Ontario Street was the economic heart of St. Catharines. Three shifts a day, thousands of men and women walked or took the trolley to the brick gates of the plant. Inside, the plant hummed and clanged as transmissions were assembled and shafts machined. Trains streamed toward loading docks on rail arteries that slinked through town, kids sometimes swinging on the slow-moving cars for a short-cut to school. In the winters, great clouds of steam poured from the soaring smokestack as it carried exhaust from the great boilers that heated the complex and fired furnaces that treated axles.

Neighbourhoods were built around the plant to house the workers, and generations of families lived their lives within sight of the complex that spread over fifty-five acres. They worked hard, proudly producing quality car components that were shipped to assembly plants across North America. They formed unions, struck when they had to, and worked hard to produce untold billions of profits, first for MacKinnon Industries, and later, General Motors. They shared stories and beers on their front porches on hot summer nights, and watched their kids play hockey on the frozen pond near the plant during the winter. They were more than GM workers: they were skilled carpenters, musicians, artists, mechanics, inventors. They bought lumber for their garages from Sawyers. They met their dates at The Duck and at Diana Sweets. They purchased work boots and Sunday dresses at Eaton’s. Yes, they built car parts, but they did far more than that: they built community.

The workers didn’t get rich, but they had a good life, full of family, solidarity, pride, community, and self-sufficiency. You breathed a sigh of relief if your son or daughter landed a job at the plant, knowing it was a union job that promised security, decent wages and benefits, and safe working conditions.

And then it stopped.

After years of designing cars, people didn’t want to buy, no matter how well made, GM sales plummeted and production declined. Costs – and workers – had to be slashed. What to do? Listening to the consumer and responding to the Japanese challenge with better engineered-cars was too difficult. And reducing million-dollar executive salaries was out of the question, so how could they cut costs? By closing factories!

Beginning in the 1990s, across North America, GM shuttered over 20 factories, throwing more than 70,000 employees out of work, shattering neighborhoods, and destroying communities. The Ontario Street plant was part of that wave of devastating closures, finally shutting down once and for all in 2010.

But reducing payrolls and production capacity was only part of the plan. Huge windfalls could be reaped by selling the factories for other industrial use or redevelopment. And GM was not too fussy about the buyer, in 2014 opportunistically unloading the Ontario Street property for $12-million to Bayshore, a company whose president had served prison time for extorting money from clients.

At the time of the sale, a full assessment of site contamination was completed by Pynchon Environmental Consultants that documented dozens of pockets of heavy metals, PCBs, chemicals, and other toxins. The report was never made public, and GM simply walked away.

Bayshore wasted no time in stripping the property. Former workers watched as lathes and foundry equipment they had worked on only months before were carted out of the abandoned plant on flatbed trucks. Copper was stripped from ceiling wires, leaving heaps of asbestos and acoustic tiles strewn on concrete floors. Whether sold as scrap or working machinery, anything of value was ripped from the building and shipped out of town, eventually realizing a reported $15-million in salvage fees. Following this, a half-hearted surface demolition began, but it had become clear to everyone, especially those living near the catastrophe, that the promise of a $250-million mixed-use development announced with great fanfare in 2014, in part by Mayor Sendzik, was an illusion, and after many buildings were bulldozed, bricks taken for scrap, and rotting boards pushed into heaps, all activity ceased.

And so it sat.

Until local residents like Susan Rosebrugh said enough is enough and began taking their health and safety concerns to Council. Until adjacent neighbourhood associations began demanding action. Until Peter Russell and others said, “We have to tell our City we’ve had enough. We have to tell them this is a mess they need to take responsibility for cleaning it up” and started a petition.

In a few weeks’ time, volunteers had collected over 2,000 signatures, many from men and women who had once worked at the plant, angry at the disregard GM had showed for the safety and well-being of its former employees and indifferent to the dangers their irresponsibility created for the community. “It’s about time!” was heard over and over as people who had grumbled about the shocking state of the site for years grabbed the pen and asked, “Where do I sign?”

The community that had lost not only their jobs but also their voices with the shuttering of the GM plant began to stir again. Demands were made for action, not talk or excuses for why nothing could be done. It did not have to be this way, the people said, and it was time to hold those responsible to account.

Their voices, clear and unexpected, jarred the City out of its stupor. Money was allocated, promises made – but again little really changed.

However, despite the Ministry of the Environment (MoE) lying about its “regular monitoring” of the site – in fact it had not been on the property since it sold – the City did convince them to carry out minimal environmental testing, and first results confirmed what had long been suspected – the site is not secure. Groundwater with PCBs and heavy metals are migrating off the property and, at the very least, into 12-Mile Creek.

The people of St. Catharines have been betrayed, first by GM who cynically closed the plant heedless of the personal pain it caused or of any obligation on their part to ensure the land they left behind was not a toxic nightmare for the City to figure out. Then, by developers whose only interest was short-term profit with no commitment to the wellbeing of the larger community. And by mayors and council, present and past, who watched the catastrophe unfold with, apparently, insufficient legal checks or recourse to respond adequately when the scheme stalled.

But St. Catharines is a resilient city whose community members have always stood up for what was right. Whether voting out the corrupt cabal that ran the Conservation Authority or walking picket lines for weeks to win concessions that would benefit future generations of workers, St. Catharines folks are a patient lot but ready to act when pushed too far.

That spirit is being rekindled, and community members are saying to our mayor and council, “We’ve had enough. The time for talk is over. It’s time for action.”

It is time for…

- the City to fully commit to cleaning up this mess. We neither expect nor want the City to absorb cleanup costs. What we do expect is leadership and aggressive action to hold polluters to account and to mobilize federal and provincial funding.

- the City to act with transparency and genuine collaboration. If you want our support, input and assistance, make us full partners, not objects who aren’t capable of comprehending issues and weighing options. Otherwise, we’ll see you at the next election.

- GM to acknowledge its role in the toxic site it has left behind and contribute to its remediation. In its current state, rehabilitation to allow for the mixed-use development that could be the renaissance of St. Catharines is almost cost-prohibitive.

- to persuade federal, provincial, and regional governments to help out. No single level of government could or should clean up this site. All levels benefited from taxes; all levels now bear responsibility.

- to adopt a community-led initiative to clean up and renew the site. Public hearings are not enough. City leadership must ensure a meaningful role in development planning and implementation for community members at every step of the cleanup and renewal process.

- the City to stop waiting for a developer to sweep into town and take the problem off its hands. Even if there was an interested purchaser, that would be no guarantee of timely environmental remediation or a final development that served the community rather than profits.

- the City to champion site cleanup and renewal rather than obstruct it. People look to you for leadership. Do it.

- the MOE to do its job. No on-site sampling has taken place since the property changed hands. Initial statements that the MoE regularly monitored the site proved to be inaccurate. Recent tests and examination have shown environmental hazards on the site and migrating off of it. The MoE is there to protect the health and environmental interests of the community. Do your job.

Whether the site remains a toxic ruin or is redeveloped into the renaissance mixed-use development it could be, will determine the future of our city. Citizens of St. Catharines, your community needs you. It’s time to begin rebuilding. •

This article was originally published on the Coalition For A Better St. Catharines Facebook page.