Health Workers: From Praise to Protection

Crises sometimes bring out the best in society, and sometimes – or even at the same time – they clarify what is so darkly wrong within. In the particular case of the commitments and risks taken by the front-line workers that we apparently value so deeply now, the contrast lies in how little they were valued before. And even now as so many praise these workers, the response falls so wretchedly short of protecting them as best we collectively can.

Of the many dilemmas that emerged from the sudden, if not completely surprising, surfacing of the pandemic, one was a shortage of personal protective equipment. This was particularly so in regard to N95 masks. The Canadian government had ordered over 100 million such masks when the crisis broke out but – stunningly – less than two million were delivered in useable form. With international supply chains disrupted, international competition for such masks so intense, and US President Donald Trump threatening to limit the export of such masks to Canada, the Ontario government scrambled to find domestic companies in Canada to produce personal protective equipment (PPE).

The Right to Protective Equipment

Meanwhile, many employers in care facilities argued that the N95 masks are, in fact, only needed in special circumstances. There is good reason to believe that this is less a scientific argument than a rationale in the face of the shortage. In any case, however, the basic principle in protecting the health of those affected is that if there is any doubt, to err on the side of precautionary actions.

This was confirmed in a ruling by Ontario’s Superior Court of Justice. On April 22, in a case that pitted the Ontario Nurses Association against the management of four long-term care facilities (the respondents), the court “ordered the respondents… to provide nurses working in their respective facilities with access to fitted N95 facial respirators and other appropriate PPE when assessed by a nurse at point of care to be appropriate and required.”

Producing the Needed Protective Equipment

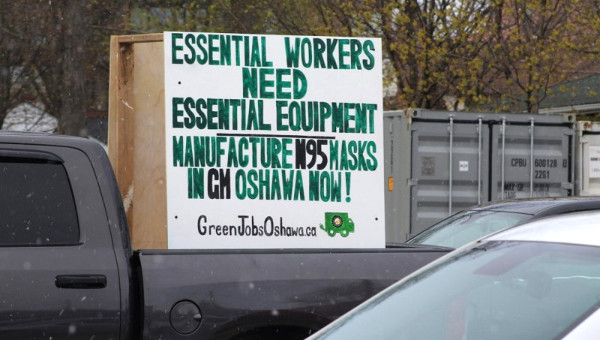

The unsuccessful quest for sufficient protective equipment was a reminder, even to many ‘globalizers’, of the importance of maintaining a measure of domestic manufacturing capacity. The weakness of Canada in this regard adds significance to the massive General Motors facility sitting idle in Oshawa. On April 9, Green Jobs Oshawa, with the support of other allies, called for the production of N95 masks in Oshawa.

On April 24, GM issued a press release stating it was in the process of negotiating an agreement with the federal government. And on May 26 GM announced that it formalized that agreement to use a part of this recently-abandoned facility to make a million masks a month, 10 million in total. This came almost two painful months after GM, facing presidential criticism in the US, had declared it would make masks at its plant in Warren, Michigan.

The Michigan plant, smaller than the Canadian facility, nevertheless, makes triple the numbers produced in Oshawa. More importantly, while the Michigan plant intended from the start to move on to making the N95 masks that are so crucial to front-line health workers still so hard to come by, the Canadian plant has no such intentions. At best, GM doesn’t “rule out making other products if the government asks.”

That GM is doing anything to address social needs is, of course, welcome. But the corporation’s feigned disbelief when criticized for not doing enough is something else. GM Canada’s vice-president of Corporate and Environmental Affairs, David Paterson declared “he was ‘befuddled’ by the demand to make N95s” and lamented, rather bizarrely, that “No good deed goes unpunished” – the ‘good deeds’ referencing not the workers doing the risky work, but GM. The GM VP concluded with a dismissive “There are others who can make N95s.”

Is it really so baffling that workers are clamoring for N95 masks when over one in six of all those infected in Ontario – one of the highest such ratios in the world – are front-line health workers? (Looking at only the infected population under 60 years old, some 40 per cent are front-line health workers.) And though there may indeed be ‘others’ who can potentially make the desperately-needed masks, even now, precious few companies in Canada are significantly closing the gap. In that context, and with GM’s Oshawa plant standing there so empty and so inviting as a potentially major contributor, what many find ‘befuddling’ is GM’s disconcerting, if not arrogant, disdainful dismissal of the notion that they too might contribute to the making of the N95 masks.

The Political Silence

However, expecting GM to voluntarily do more would be naïve. GM doesn’t lack for economic weight and impressive technical and logistical skills, but its orientation is to making profits, not to meeting social priorities. GM may have an interest in having an internally-produced ready stock of Level 1 masks for their own workers (and those of suppliers) as production ramps up. GM may also have reasons to make a modest nod to making protective equipment as a positive public-relations exercise. And it may even be the case that top executives were genuinely moved to contribute in some way to fighting the pandemic. But a decisive mobilization of GM’s resources to focus on the social crisis would demand a political response. It would require direct intervention by those elected to allegedly represent us.

Much has been said about how unprepared provincial and federal governments have left our health system to deal with such emergencies, as – against the advice of health workers and their unions – they steadily undermined the quality of our health system (with, it needs adding, the general support of business). To this must be added the debilitating policies of leaving our manufacturing capacity to the winds of globalization and private corporate interests, which, in turn, left us without the manufacturing capacity to produce the equipment we now need.

Yet even if we had the necessary manufacturing capacity within Canada, as long as it resides in private companies competing for profits, this too would be deficient. From what we know, our governments were too timid to even forcefully ‘ask’ GM to make the crucial N95 masks. They were certainly not ready to mobilize public pressure as part of cajoling GM to show greater commitment to social needs.

Above all, what has been missing has been a readiness on the part of the Ontario and federal governments to use their emergency powers to mandate companies to respond to the scale of the health crisis. Back in mid-March, Prime Minister Trudeau ‘left the door open’ to the possibility that Canada would invoke its emergency powers to increase the production of medical equipment, but no moves in this direction have as yet occurred. This would involve coordinating such production across the country, including the requisitioning of patents, supplies, and materials as needed – something akin to, if perhaps not on so large a scale, the compulsory conversion of civil production to military production during the Second World War.

Back to Normal?

Social distancing and lockdowns leave people understandably longing for a return to ‘normal’ even if, when pressed, they know well many of the limits of the past. But it is not at all clear that a return to the old normal is an option. The shadow of death may have prioritized a degree of mutual care in our minds, but the winter of having to pay off the fiscal debts accumulated in the interim may instead add material pressures for austerity.

As the memory of this crisis fades, we may fall victim again to suffering not only more inequality and insecurity but a further erosion of our already thin democracy. And we may once again find ourselves unprepared and surprised by another pandemic or other crisis. One such defining crisis – the looming environmental catastrophe – is already in waiting, already begging for decisive, too-long delayed, conscious and dramatic action.

The future isn’t encoded, it’s not a prediction, it’s not a hope; it is a project, something to be made. Passively waiting for it to ‘unfold’ is the greatest danger. •

This article first published on the Canadian Dimension website.