‘Poorly Behaved Nurses’ and Inequality in SA’s Healthcare Sector

Nurses in South Africa get a bad rap. Whether by journalists, politicians, academics, patients or bosses, nurses – particularly in the public sector – are criticized, vilified and scrutinized. Little consideration is given to the trying context in which they work.

Nurses hold 81 per cent of filled professional positions in the public healthcare sector and carry the bulk of responsibility of paid care in a country that in 2019 achieved “the most unhealthy nation in the world” status in the Indigo Wellness Index. The index ranks countries according to measures of blood pressure, blood glucose, obesity, depression, happiness, alcohol use, tobacco use, exercise, healthy life expectancy and government spending on healthcare.

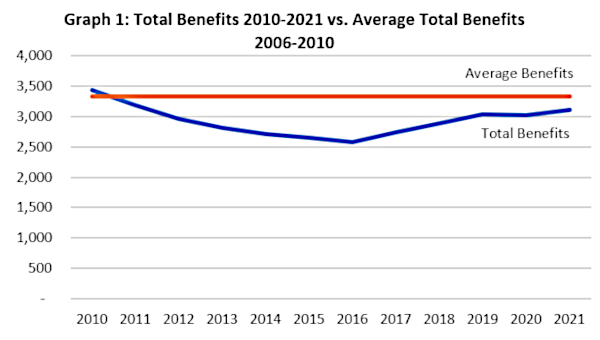

The last on this list – government spending on healthcare – is a key link I make to the bad rap given to nurses in a recently published article, “Public Healthcare Spending in South Africa and the Impact on Nurses: 25 years of democracy?”

The article is part of feminist journal Agenda’s attempt to evaluate 25 years of South African democracy from a feminist economics perspective.

Public Healthcare Under-Spending

As a researcher studying public healthcare financing globally, it was surprising to me how the recent history of South Africa’s public healthcare spending is disputed terrain. Though many health activists and workers know that government expenditure on public healthcare has been low in democratic South Africa, this is not the story told in current health systems literature.

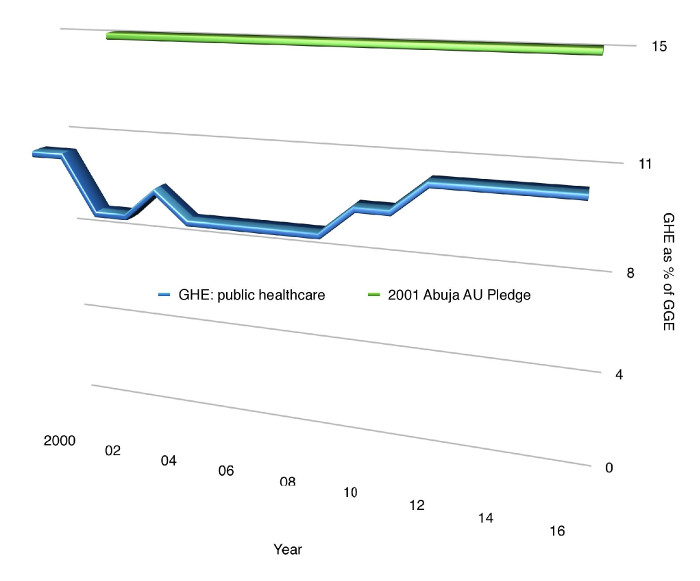

I graphed the latest World Health Organization (WHO) data (graph below), to show that South Africa has consistently fallen below the 15% level of government expenditure on health (as a percentage of general government expenditure), agreed to by states in the 2001 Abuja Declaration on HIV/Aids, Tuberculosis and other Related Infectious Diseases. This despite South Africa’s relatively high status in Africa as a middle-income country and its exceptionally high levels of disability, and premature death caused by disease and violence.

Looking at nursing labour supply, South Africa ranks much lower than several middle-income countries, at 49 nurses and midwives per 10,000 people. For instance, Libya’s ratio of nurses and midwives to population is 70 per 10,000 people, Brazil’s is 75 and Russia’s is 89, and all have higher life expectancy at birth than South Africa. Since 1998, South Africa’s ratio has risen only slightly, from 41 nurses and midwives per 10,000 people to 49.

Added to this overall low supply of nurses is the filtering of nurses from the public to private sector. From 1995, the private health sector was permitted to grow rapidly in South Africa, as pointed out by some researchers as early as 2002.

Being the backbone of a health system, nurses were increasingly needed in the private sector and the proportion of private-sector nurses doubled between 1994 and 2014, from 21 to 42%. Comparing workload, nurses in the public sector serve six times more patients than private-sector nurses, explaining one of the main reasons why nurses would be inclined to make the move from public to private.

This imbalance reflects a larger inequality: 17% of the population is covered by private medical schemes and associated private healthcare providers – representing about half of the country’s total health spending – while 83% rely on a dwindling number of nurses and the underfunded public healthcare sector that nurses sustain.

The impact of all this on public sector nurses is immense. It includes staff shortages, excessive workload and workplace abuse. Examples of nurses’ everyday experiences help make the connections between high disease burden, inadequate public healthcare spending, unequal apportioning of professional health workers and what is perceived, and experienced as poor nurse attitudes.

Studies across the country from the late 1990s point to staff shortages and workload as the major stressors of nurses. A 2006 study of 1,780 nurses in nine provinces, for example, highlighted insufficient staff to handle the workload, staff shortages and poorly motivated co-workers as the most severe stressors identified by nurses.

In 2011, the National Department of Health itself estimated a professional nurse shortage of 44,780, with high numbers of vacancies and unfilled posts in the public sector.

A 2015 study of mostly public sectors nurses in Gauteng and Free State showed how workplace constraints prevented nurses from upholding the International Code of Ethics for nurses and the South African Nurses Pledge of Service. Nurses named being blamed by managers for problems stemming from staff shortages and other systemic inefficiencies as the main barriers. This offers another take on popular views questioning the ethics of nurses.

Nurse managers, often cited as problematic by non-management nurses, also face trying working conditions stemming from staff shortages and other systemic deficiencies. A study of nurse managers in medical, surgical, paediatric and maternity units in nine Gauteng and Free State hospitals found that nurse managers were performing an average of 36 different tasks per hour, many unplanned, fragmented and of short duration.

In addition to having to compensate for systemic deficiencies like water shortages, nurse managers in primary healthcare hold little decision-making power in complex chains of command. These consist of district managers on top, area managers and clinic supervisors in the middle, and nurse managers at the bottom.

Given such stressful working conditions, as in other countries, workplace abuse and violence are commonplace for nurses of all types in South Africa. I have demonstrated similar connections for nurses in Ontario, the largest province of Canada, where public healthcare is underfunded and the supply of nurses is low.

In a 2017 study, undergraduate nurses of various levels in nine of 16 nursing schools in South Africa reported tolerating an average of 10.5 violent events over a 12-month period. Being treated differently due to undergraduate status, being subjected to nasty, rude or hostile behaviour, and being shouted at in rage are some of the forms of violent behaviour identified.

Returning to nursing labour supply, a 2009 study found that only 13% of undergraduate nursing students in South Africa complete their studies. Poor working conditions, intra-professional violence and underfunding help explain this as well as the slow growth of the nurse workforce.

Nurses in South Africa get a bad rap. Nevertheless, over the first 25 years of democracy, they have shouldered the bulk of the weight of massive inequality as it manifests in illness requiring professional care. If we can acknowledge massive inequality as readily as we do, it is time we acknowledge the necessarily grinding task and vital labour of nurses. •

This article first published on the dailymaverick.co.za website.