Germany: A Left-Wing, Grassroots Orientation for Die Linke

Antoine Larrache (AL) (International Viewpoint): How do you see the situation in Germany, especially the repercussions of the economic crisis?

Violetta Bock (VB): The defining feature of the situation in Germany is the decline of the ‘old West’. This applies both to its military and geopolitical role in the US-European alliance and to the economic basis of that alliance: the era when Germany occupied a leading position in European industry and played a dominant role in the global economy seems to be over for the time being, and there is currently no indication that this evolution could be halted or even reversed.

For years, production chains and growth have been increasingly shifting to Asia, particularly to China and India. In Germany, this development is not sufficiently understood, neither by the current government nor by large sections of the social left and the trade union movement, nor does it constitute the basis for considering future actions.

This is a dramatic situation because everything we are witnessing today is taking place under the banner of these economic changes, in the context of a rapidly progressing climate catastrophe, with all its social and political consequences. For the working classes, this translates into a strategic vacuum.

The climate catastrophe is now recognized as a reality, but serious reflection on its consequences is being supplanted by the social and economic crises that are developing alongside it. In truth, society should be investing in future projects that strengthen civil protection and social infrastructure, that enable people to cushion the consequences of the climate catastrophe and, at the same time, prevent the continued destruction of our living conditions. Instead, war, geopolitical competition, and the defence of national industrial sites are taking centre stage. Investments are being made for war, exploitation, and plunder – in other words, indebtedness and social dismantling are being made to serve the military-industrial complex and everything that guarantees control over natural resources at the international level. This is where the profits and expectations of the ruling classes lie.

This significantly increases the pressure on the working classes, both materially and ideologically: on the one hand, through nationalist propaganda and the desire to widely militarize industry and society – in Germany, this is always done on the theme of ‘the Russians are coming’ – and on the other hand, through the deindustrialization of the country, which destroys jobs and living conditions.

Germany, while remaining a central power in the EU, does not have the global banking power of Great Britain, the military supremacy of the United States, or even the dominant economic position of China. Even in the upper echelons of the trade unions, there are leaders who hope that, on balance, militarization will benefit them and that Germany will manage to regain ground in the race for competitiveness, with their help if necessary.

This also hinders daily struggles. As long as there is no strong hope for a better future, any movement will remain hampered. This is the task facing today’s left.

AL: What role does the far right play in this situation?

VB: The AfD is a heterogeneous collection of right-wing currents. It initially criticized the European Union and mobilized the so-called middle class, although its electoral base was from the outset largely made up of working people who felt let down by the political system.

Today, the spectrum ranges from conservative-nationalists and advocates of drastic economic liberalism to outright fascists who manage to present themselves as a radical opposition; they have, however, been trying for a long time to offer their services to the CDU as a government partner.

Through ongoing polarization, they have firmly entrenched their racist agenda within society, and their demands – such as the dismantling of the right to asylum – have been taken up by other parties and translated into government measures.

We are currently witnessing a shift to the right across the entire political spectrum (with the exception of the Left Party), which is making life more difficult every day for migrants, workers, LGBTQ+ people, and all socially vulnerable people.

The fear of the emergence of a mass fascist movement is prompting a search for a central response within the framework of the broadest possible alliances, extending up to the CDU/CSU, the SPD, and the Greens, in order to block the AfD at all levels. There is currently no mass fascist movement in Germany.

But we must expect that the CDU, the SPD, and even the Greens will be able to find political common ground with the AfD – in practice, this already exists. This is precisely what we must oppose…

In recent months, we have witnessed not only a shift to the right but also a polarization, visible particularly in the growth of the Die Linke (The Left) party. A growing segment of the younger generation is seeking more radical responses and is ready to take action. Responses to the shift to the right must therefore not focus on alliances against the AfD but must also put forward a socialist perspective as an alternative to militarization, nationalism, and social disintegration.

AL: How are the unions reacting?

VB: We regularly face vicious attacks on the right to strike and trade union rights. The current government, for example, openly attacks the eight-hour working day. In the 2000s, German trade unions missed the opportunity to shed their illusions in social democracy. Admittedly, there are now a considerable number of union officials who are firmly on the left, but at the same time, there are far fewer working-class leaders in the workplaces. This is a development that was emerging in the 1980s. At the same time, the social conflicts that focus general attention are on the decline, after a brief resurgence at the end of the last decade and the beginning of this one.

We are not currently seeing any major high-profile struggles like those that took place a few years ago at Amazon, the postal service, hospitals, and the civil service. Of course, there are always important initiatives and campaigns that give us hope and that we must support with all our might. To do this, so-called organizing methods1 are increasingly being implemented. But they remain closely linked to the frameworks, decisions, and perspectives set by the central trade union apparatuses.

We are also witnessing the emergence of right-wing works councils, particularly in small and medium-sized enterprises, and the creation of competing right-wing unions. Addressing this requires militant trade-union work because they attack where it hurts: works councils and commissions responsible for negotiating collective agreements are constantly making compromises that ultimately do not reflect the wishes of their colleagues.

A fundamental task remains to form core groups within workplaces that are dedicated to highlighting class contradictions and developing a social perspective. But without a socialist organization capable of presenting what the next step should be and also of bringing it to a successful conclusion, we will remain stuck in the stage of defensive struggles. This is exactly what we are currently experiencing: many small struggles but practically none that manage to impose themselves in the social debate. In the service sector, efforts have been made to form citizen coalitions for this purpose, for example by cooperating with the movement for energy transition in transport during wage negotiations on public transport.

Our comrades in the workplaces are striving to transform, democratize, and radicalize trade union work, but often also simply to reorganize it. The Left Party can be of great help in this regard but not if we lock ourselves into workplace cells that attempt to implement our party politics outside of this trade union work.

AL: What form does the policy of social democracy take?

VB: In times of crisis, the SPD has always been unable to develop an independent policy in the interests of the working classes because for the SPD, success is inseparable from that of capital. Nothing has changed in this regard.

And as it has largely lost its roots in the working class, it is making less and less of a pretence of pursuing class policies. It is gradually disintegrating.

In my opinion, the role of the Greens is more interesting. Abroad, people often underestimate the importance the Greens have or have had in German society – they recently fell behind Die Linke in the polls. They have long represented a hope for renewal: ecological, progressive, pacifist, even if, in reality, they have always bowed to the interests of capital and reaction and led Germany into its first wars since the Second World War.

Today, they are at the centre of society, but they have become the party of ‘human racism’, which keeps borders open for the benefit of capital, and that of ‘humanitarian war’. They have become an important party, especially among the middle class, but the betrayal of their own origins is, in my opinion, already ancient history.

Those who vote for the Greens now know quite clearly what they will receive in return: a policy in favour of capital, with electric cars and organic coffee pods.

AL: What policy do you think Merz will pursue?

VB: It’s not yet determined. The CDU – and with it the SPD, its coalition partner – faces a dilemma. They are resorting to the well-worn standard capitalist recipe: draconian social cuts, the militarization of society, closing the EU’s borders to refugees, and massive investments in European capital. They hope to create new room for redistribution through a new ‘economic miracle’.

But there are good reasons to believe that this time, in the context of the general economic crisis, they will not be able to get out of it with a cornucopia of euros – the economic crisis is, in fact, accompanied by profound international upheavals in modern modes of production, alongside an imperialist reorganization of the relationships of forces. The rearmament programme alone will not be able to change the situation – it will only increase and spread the risk of war.

At present, we see the CDU/CSU and the SPD increasingly aligning themselves with the racist and nationalist slogans of the AfD. Why then would it not be possible for Merz to one day dare to take the plunge and form a minority government supported by the AfD? This would be disastrous for the people of Germany, but it is a realistic scenario.

The bourgeois media and major industrial groups are pushing with all their might to bring about a conservative-style government. They are constantly talking about crises within the coalition, turning every disagreement into a catastrophe, and defending a concept of democracy according to which governments must be able to ‘force things through’ without challenge or discussion, arguing that this is simply a necessity imposed by this crisis.

This is precisely where we socialists can sharpen our profile: we are democrats. We take diversity of opinion and open conflict seriously, because we assume that collective solutions can only emerge from confrontation and broad participation. This is a completely different conception of democracy from that of the authoritarian ‘forcing through’ of the bourgeois centre.

AL: Can you talk to us about Die Linke? What is its general political orientation? What has been the impact of the massive influx of young people?

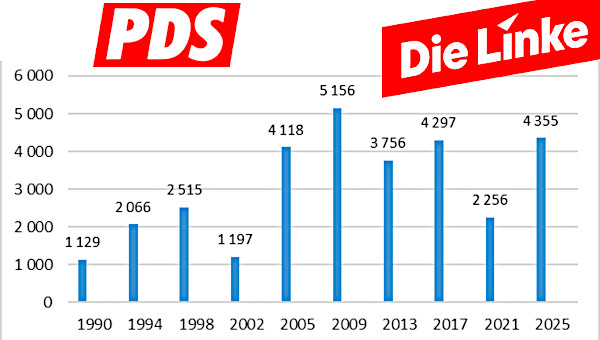

VB: To fully understand Die Linke, one must know its history. Initially, the party was the result of the merger of two factions: the successor organization to the former state party in the East – the PDS – and the Electoral Alternative for Work and Social Justice (WASG), which emerged in western Germany.

The WASG emerged in the mid-2000s as a reaction to the Schröder government’s radical offensive against social gains, the so-called ‘Hartz reforms’. It was fuelled by disillusioned members of the SPD but also by elements from the more radical left, many of whom had a Marxist orientation.

From the very beginning, it was clear that Die Linke was not just another political party but rather the product of the coming together of different experiences and traditions, both politically and between East and West. Its appearance has changed several times throughout its history, and it will continue to evolve in the future, because its success has always been and always will be linked to its ability to adapt to new social dynamics.

Today, Die Linke – and this is where a misunderstanding often arises – is less a party in the classical sense of the term than a mass organization, a mass rallying point.

What do I mean by that? It certainly defines political orientations but does not impose on its adherents that they be followed uniformly, preferring to put them up for discussion within the movements. It brings together both pragmatic left-wing social democrats and revolutionary socialists, without this generally leading to divisions, exclusions, or lack of solidarity. Everyone is aware that it is a common project that must be able to accommodate different currents. Its central objective is the defence of social gains, associated with the debate and the struggle for a socialist perspective, taking into account diverse experiences, from the point of view of the history of both East and West Germany and that of the different movements.

The political orientation of Die Linke is therefore difficult to summarize in a single sentence, and this is precisely where many observers stumble. They want definitive, unambiguous words, but that’s not how this party operates. Its orientation is determined by the people who are active in it.

This is one of its strengths: those who get involved can influence how the party’s work evolves. The line followed on central issues is constantly evolving and adapts to the movements.

The debate on how to address the rise of the far right is one example: some call for broad alliances against the AfD, including within parliament, while others want to show that there is more room for manoeuvre in capitalism. I, for example, oppose both positions. In reality, the objective room for manoeuvre for reformist strategies in Europe, and particularly in Germany, has shrunk in a context of deindustrialization and authoritarianism.

We currently find ourselves in a rather comfortable, but difficult, situation: the party has more than doubled its membership, many come directly from social movements, others belong to a generation that is only just beginning to become politicized. The mere fact that these young people have decided to make Die Linke their organization is already significant. They are thus deliberately turning away from the Greens, a party often considered liberal-left but which, in reality, partly advocates liberal-right policies. This generation has become aware that the entire party system in Germany has shifted to the right and that only Die Linke has remained in its place: as a force of hope, as a pole against exclusion and disenfranchisement.

AL: And what do these young people expect from the party?

VB: I think what they want is not the satisfaction of specific demands but rather to be part of this opposition that brings hope. In the best-case scenario, and this is what we see in many places, they see in Die Linke a space where they can act effectively in politics. What has also made it possible to get to this point is the fact that since Sahra Wagenknecht’s departure, the party has managed to get away from public quarrels, that it has managed to find a central theme with the question of rents, and that with the door-to-door campaigns it is possible to start acting at a basic level and, outside of small, closed circles, to establish contact with people on the basis of what they experience on a daily basis.

We have a historic opportunity here: the MPs and party officials are in the position they are today because they chose to embark on this project at a time when it seemed impossible to make a career in politics this way. As recently as last autumn, Die Linke was considered finished. Everyone who stood for election did so with the deep conviction that a left-wing alternative was needed. This is precisely what we can take advantage of today to build the future.

AL: Regarding the Palestine solidarity movement: is there a new dynamic, particularly in working-class and immigrant neighbourhoods?

VB: The Palestinian solidarity movement is currently one of the largest movements in Germany. It is primarily led by immigrants. As in many countries, repression is severe and serves to further fuel racism. It is therefore always important to distinguish between ‘published’ opinion and public opinion. Among the population as a whole, there is a majority against arms deliveries from Germany, but this is not yet evident on the streets.

You will no longer be able to reach young people, but also many workers and certain sections of the population as a whole, if you broadly characterize solidarity with Palestine as a ‘problem’ or ‘anti-Semitic’. This view has long permeated the social left, not least because of Germany’s terrible history.

Of course, it remains true that the more people are tied to state institutions in their daily lives – whether through their work or in their private lives – the more the old pressure of ‘reason of state’ is felt. This remains an obstacle.

But this does not pose a major problem for a socialist strategy because we are addressing ourselves above all to those who are not integrated into this system but who suffer from it. And this is precisely where solidarity with Palestine, despite all the attacks, takes on a new dynamic.

AL: How is the struggle against repression going? Can it be overcome? Can the movement become stronger than the repression?

VB: Of course, repression has an effect, particularly on those who work or act closest to the state or who are in some way dependent on state institutions. In some places, repression is becoming apparent, for example, when Jewish women are banned from speaking out publicly because they clearly oppose Israeli policies, or when courts condemn brutal police interventions after the event and later lift bans on certain slogans. Within the solidarity movement, we regularly see new advances as new sectors of the population join the movement and significant breakthroughs are made.

The fact that more and more organizations can no longer turn a blind eye has also contributed to this. Those who have once managed to overcome their fear are all the more determined. The state’s attitude is shaking many people’s fundamental trust in the system. Within the solidarity movement, there is still a wide range of positions, from an emphasis on humanitarian demands to anti-Zionist positions.

The major problem in Germany at the moment is quite different: the fight against depression and the feeling that there is no way out. The federal government has long stubbornly refused to decide on anything that might put pressure on Israel. So we are against the state, but the state is not budging. The German ‘reason of state’ hovers over everything and permeates the entire foreign policy.

Many activists therefore feel as if they are tilting at windmills. For those who have been campaigning in solidarity with Palestine for decades, this period is dominated by the horror of what is happening in Gaza, the West Bank, and throughout the region.

And at the same time, this phase marks a major step forward: a new generation of activists and party members has come to the forefront, no longer held captive by the idea that any criticism of Israel is inherently anti-Semitic. This progress may not have an immediate impact, but it creates a solid foundation from which we can build a more radical internationalist perspective in the years to come.

AL: How do you see your role as a Member of Parliament in this situation?

VB: I always approach my role as a Member of Parliament with the question of the relationship between Parliament, movement, and party in mind.

Fortunately, in recent years, there have been many debates and clear progress within Die Linke. We have learned lessons about how this relationship should be structured and have introduced precise rules, for example, for financial payments or the regular holding of social consultations. It is very clear that the MPs I work with today did not run for office out of professional ambition but out of conviction. Of course, there remains an old way of functioning within the party, in which MPs tended to organize themselves into small working groups. Such tendencies regularly resurface for structural reasons. But we have begun to break this logic. And I think we are on the right track, even if we are only at the beginning.

Concretely, I distinguish three aspects in my work.

First, we must ensure that movements can benefit from existing resources. I’m not talking primarily about money but rather about information, networks, and opportunities to be heard. This is often reduced to simple financial support. But what is crucial is providing movements with analyses, theses, evaluations, impressions, and a good understanding of the opponent. These are resources that we have at our disposal as MPs.

Second, it’s about being a role model. We shouldn’t attach to this role the goal of one day becoming part of the ruling bloc of the powerful and the government. As MPs, we must show that we don’t disappear as soon as we’re in the Bundestag. In Kassel, especially in the Rothenditmold district, I founded a community centre with many comrades. After my election, many wondered if I was now ‘gone’.

But for me, one thing was clear: work in parliament and local roots must not be contradictory.2 That is why I continue to do social counselling, that is why I support the tenants’ movement – which, in this crisis situation, has become, and this is no coincidence, a central area of activity for the entire party. In this way, we are proving that it is possible to work within the bourgeois parliament without becoming ‘parliamentarians’.

Third: We must use the parliamentary platform in a landmark way. In these times of war and climate catastrophe, it is important to give the struggle for climate justice and against imperialist interests the greatest possible visibility. This is the great task before us, but it must not be dissociated from the class struggle as it is actually unfolding. On the contrary, it is an extension of it. I would be happy if, in two or three years, precisely these issues – organizing work, grassroots work, and activity for and with the working class – formed the basis of our internal party debates. And I am confident in our ability to contribute to this. For we have already shown that an orientation anchored to the left and to the grassroots is not a caricature but actually allows us to score points in times of polarization. •

This interview first published on the International Viewpoint website.

Endnotes

- Violetta Bock is the German translator of the landmark book The Seven Components of Transformative Organizing Theory by Eric Mann, director of the Labor/Community Strategy Center in Los Angeles.

- Violetta Bocka has written, in collaboration with our comrade Thomas Goes, Ein unanständiges Angebot? With linkem Populismus against Eliten and Rechte (An Indecent Proposal? Left-Wing Populism Against the Elites and the Right, 2017.). In it, they advocate a “socialism for ordinary people” and “the organization of a counter-power in order to create laboratories of hope and a hinterland of solidarity.” They also describe Sahra Wagenknecht as a “failed populist.”