Allan Gardens, Toronto: Protest and Public Space

For centuries, various Annishinaabe First Nations – among them the Mississauga, Ojibwe, and others – inhabited territories on the northern shores of Lake Ontario, one of the Great Lakes that constitute part of the border of Canada and the United States. Canada’s leading industrial province, Ontario, and its largest city, Toronto, were created through processes of colonization consolidating British dominance in the northern reaches of the Americas in the aftermath of the United States War of Independence, which commenced in 1775. This colonization, rooted in longstanding and ongoing dispossession of Indigenous Peoples, was marked by the creation of Upper Canada (Old Ontario) in the Constitutional Act of 1791. The nation state’s territorial consolidation continued into the 1860s with 1867’s British North America Act, which established the Dominion of Canada.

Colonization, and the capitalist development that accompanied it, was premised on Indigenous lands belonging to the British king. In recognition of First Nations military and trade alliances with their “father,” the monarch, there was limited acknowledgement of “Indian territory” and First Nations entitlements to its use. A number of vague treaties and transactions known as “surrenders” and “purchases” transferred vast tracts of land to the British Crown over the course of the 1780s, with Indigenous groups displaced to small, isolated reserves. Hundreds of thousands of acres constituting an Indigenous commons were privatized, transformed into a land market of commodified property. More choice locations, like present-day Toronto, as well as untold forested territory, future sites of mining riches, and potentially rich agricultural acreage quickly became designated “Crown land.” A Mississauga chief complained to an English official in the 1820s: “You came as wind blown across the Great Lake. The wind wafted you to our shores. We received you – we planted you – we nursed you. We protected you til you became a mighty tree that spread thro our Hunting Land. With its branches you now lash us.”

1860: Opening of Allan Gardens

In 1830, William Allan, a mercantile banker and pillar of Upper Canada’s aristocratic ruling oligarchy, the Family Compact, purchased a large swath of Crown land running from Lake Ontario into what is now mid-town Toronto. Decades later, after his death, Allan’s son George, the mayor of Toronto and president of the city’s Horticultural Society, ceded a small portion of this lucrative plot to the municipality for its use, which included the creation of gardens. During a visit to Toronto in 1860, the Prince of Wales formally opened Allan Gardens.

For more than a century and a half, Allan Gardens has nurtured not only lush flora, now housed in six greenhouses but also an endless array of political protests. The urban park that sits on green space occupying two large city blocks has become notable for its association with a variety of social justice movements. These include, but are not restricted to:

- nineteenth-century suffragists;

- unemployed workers’ mobilizations of the 1930s;

- free speech campaigns in the 1960s;

- gay pride marches of the 1970s, and

- anti-poverty protests during neoliberalism’s reign from the 1990s to the present.

Few public spaces in Canada have been the sight of so many, and so varied, displays of resistance and grievance.

Indigenous Peoples, not surprisingly, have long utilized Allan Gardens as a gathering spot, and weekly drumming and healing ceremonies take place in the park to this day. In 1995, the Toronto Historical Board erected a plaque commemorating Dr. Oronhyatekha (Burning Cloud/Peter Martin), the second Indigenous person in Canada to earn a medical degree, graduating from Toronto’s School of Medicine in 1866. Oronhyatekha/Burning Cloud lived and practiced conventional western medicine as well as offering “Indian cures and herbal medicine” out of his home, located across the street from Allan Gardens. A distinguished public figure, Oronhyatekha chaired the Grand General Indian Council of Ontario and Quebec in the 1870s, where he opposed the restrictive aspects of Canada’s Indian Act. More than 100 years later, a Native Women’s Resource Centre of Toronto is now located across from Allan Gardens. It offers basic services to Indigenous women and their children, including housing, employment and education advice, relief from trauma, and access to ceremonies and traditional healers. Since October 2013, the Centre has hosted Sisters in Spirit Vigils in the park, and in 2019, it commissioned an art installation addressing the epidemic of Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls.

Feminism’s association with Allan Gardens reaches back to 1892. The National Council of Women of Canada, dedicated to achieving female suffrage, was created when 1500 women met in Allan Gardens. In 1896, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union conducted a Mock Parliament in the park’s pagoda pavilion. A theatrical presentation presided over by Dr. Emily Stowe, the first female physician to practice in Canada, and featuring Lady Ishbel Aberdeen, wife of the Canadian Governor General at the time, the send up of male dominance – not only political but cultural and socio-economic as well – was an event that showcased women’s oppression, but from a decidedly elitist perspective. Satirical commentary on political corruption, chauvinistic fashion sensibilities, and gender reversals was punctuated with the dignified background of classical music. “Well-heeled attendees,” notes historian of Canadian suffrage, Joan Sangster, were treated to the sardonic political theatre only by securing “tickets ahead of time.”

More raucous, and decidedly more risqué, were the dyke marches associated with Toronto’s Pride Week, the first of which took place a century after the Mock Parliament, in 1996. Since 2014, the march has concluded at Allan Gardens, with queer artists and activists, celebrities. and celebrants offering speeches and theatrical performances that would have caused nineteenth-century feminists to blush. Lady Aberdeen would surely have been flummoxed, if not fuming, at the 2017 Slutwalks that rallied in Allan Gardens between 2013-17, campaigning to decriminalize sex work and create a stigma-free environment for those engaged in erotic employments.

Early Twentieth Century

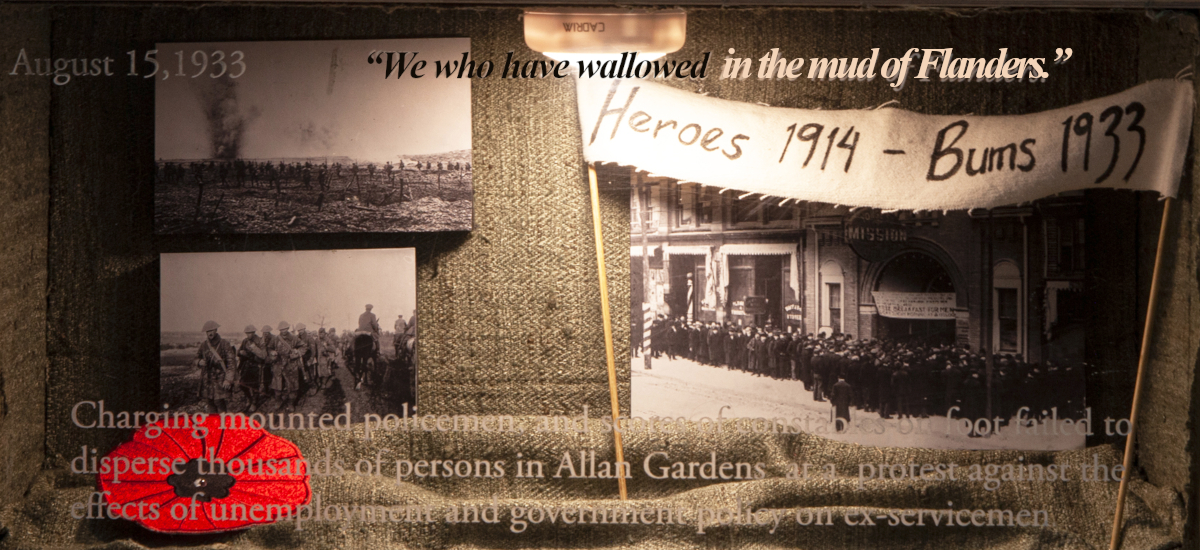

The class character of protest at Allan Gardens took a notable plebeian turn as capitalism consolidated in the early twentieth century. Unions grew in size and influence. Left-wing organizations such as the Communist Party of Canada (CP) and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) emerged to demand an alternative to the “dog-eat-dog” ethos of the profit system. Periodic crises left masses of workers unemployed, and with the collapse of the economy in the Great Depression of the 1930s, Allan Gardens became a rallying point for the discontented. Protesters and police clashed repeatedly. At one such confrontation, 200 jobless dissidents led by the Canadian Labour Defence League (CLDL) were forcibly dispersed by police. A Communist-led Workers’ Ex-Servicemen’s League (WESL) unfurled its banner – “Heroes 1914 – Bums 1933” – at Allan Gardens in the summer of 1933, protesting unemployment, police brutality, and the suppression of free speech. No orchestra serenaded their demonstration. Police descended on Allan Gardens in droves, and corps of cops on horseback and motorcycles battled the unemployed throng. Among the most indignant were militant women, who parked their baby carriages beneath trees and assailed the rampaging police. After a number of such clashes, police backed down. Under pressure from organizations such as the WESL, the CLDL, and the Toronto Unemployed Council, the Civic Parks Committee designated eight local parks open to all public speaking and demonstrations, including the provincial legislature, Queen’s Park. Allan Gardens, in the vanguard of those public spaces that witnessed pitched battles for the rights of the unemployed and others to congregate and publicly challenge authorities, was not named among the venues where protest meetings were permitted.

The 1930s Allan Gardens unemployed protests nonetheless secured the park an undisputed reputation as Toronto’s locale par excellence for rowdy demonstrations on the part of the discontented. In 1962, poets rebelled against a Toronto City By-law that prohibited anyone – with the exception of religious figures – proclaiming, lecturing, or haranguing “in or on any city park,” save for some exemptions won, in good part, in the 1930s. Oscar Wilde, however, had lectured in Allan Gardens in 1882; eighty years later poet laureate of the Canadian left, Milton Acorn, was not about to be silenced. He led a poets’ assault on the Allan Gardens free speech embargo, and won, both in the court of public opinion and in the justice system. The Toronto By-law was changed, and Allan Gardens was open to poets, soap-boxers, and free speech advocates of all kinds.

Free speech of course carries the possibility that it can be repugnant. An announced neo-Nazi rally at Allan Gardens in May 1965 brought this message to the fore. Only eight fascists showed up for the event, led by a 23-year-old attention seeking future founder of the Canadian National Socialist Party. The Nazis were routed by a 4,000-strong anti-fascist contingent, some of them survivors of the Holocaust.

The 1965 anti-Nazi riot was, however, an outlier. In the 1970s, the horticultural enclaves were a popular homosexual cruising area. This led to police, secreting themselves behind bushes, targeting gay men and charging them with “gross indecency.” One of North America’s leading gay publications, Toronto’s The Body Politic, successfully challenged one such arrest in 1979, turning the tables on the cops and their prurient crusade to cleanse Allan Gardens, making the issue of surveillance and court convictions a cause célèbre in times that were moving toward more tolerant views of homosexuality and its decriminalization. Allan Gardens became the launching pad of Toronto’s first Gay Pride march.

With Allan Gardens the kind of public space that society’s poor and disparaged gravitated to, police utilized the opportunity to victimize the scapegoated and suspicious. Race loomed large as residential areas around the downtown Allan Gardens gentrified, and older boarding houses catering to poor, often racialized Torontonians of Caribbean ancestry, gave way to posh, one-family residences. Such urban transformation takes time, however. For Blacks still resident in the Allan Gardens vicinity in the 1990s, some of them homeless and relying on shelters that continued to exist within the neighbourhood, the park was a refuge, a place to gather and play soccer. A police sweep of Allan Gardens in the summer of 1994 resulted in discriminatory and demeaning treatment of 65 black men, $3000 worth of loitering tickets, and warnings that a return to the park would result in arrests. Affluent white home owners – champions of the rising ‘Not In My Backyard’ ideology and architects of vocal local residents’ associations, cheered on the cops. But Allan Gardens could not easily be turned into a site of racist repression. Reinforced by allies in the gay movement, Black Lives Matter activists drummed and rode bicycles to Allan Gardens in 2016, their message – “I Am Not A Threat” – harkening back to the shameful profiling of soccer playing immigrants in 1994.

Twenty-First Century

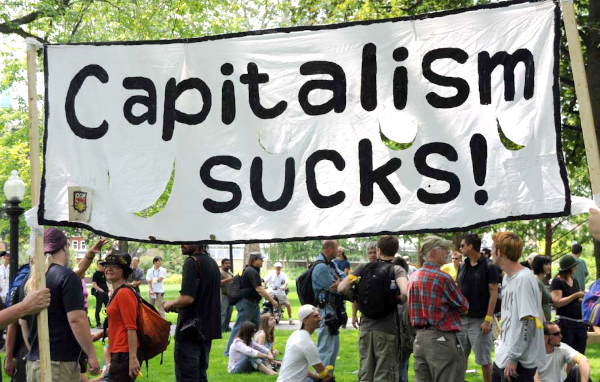

By the 1990s and well into the twenty-first century, with economies in the advanced capitalist, globalized world facing a series of crises, Allan Gardens became associated with an array of militant protests. These gatherings of dissent were almost always animated by class grievance. Neoliberalism’s successful assault on the basic defensive organizations of the working class – the trade unions – nonetheless managed to quiet labour resistance. Strikes became more and more rare. As the political spectrum shifted to the right, left-wing organizations long associated with anti-capitalism and encouraging militant uprisings of the working class faded into the background. The result was that protest became less associated with the organized working-class and traditional organizations of the radical left.

In this climate of retrenchment, in which neoliberal politics held sway, the dismantling of the welfare state, policies of economic austerity, and a grave housing crisis gave rise to increasingly aggressive anti-poverty mobilizations. A 1995 “Rap ‘n Rage Against the Cuts”, sponsored by a community radio station, drew 400 to a protest against the provincial government of Conservative Mike Harris and his dismantling of social services.

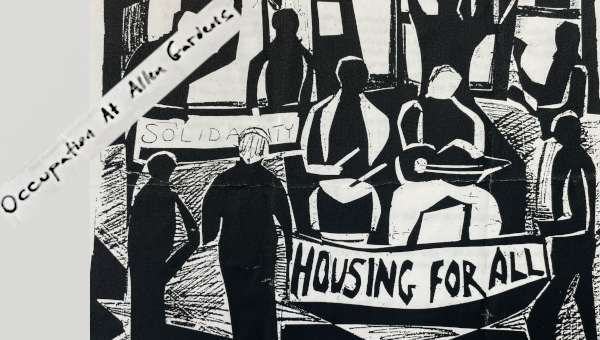

A leading organization in these years was the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP). OCAP utilized Allan Gardens to mount a wave of protests. It supported beleaguered encampments at the park, declaring Allan Gardens a safe site for Toronto’s increasing numbers of destitute and homeless people. In a three-day occupation, Allan Gardens became a refuge for over a thousand victims of the economic downturn, who received food and shelter. Routine protests culminated in Friday night “sleepouts” at the park, which last 120 days. Protest marches against Ontario’s provincial governments often commenced at Allan Gardens and wound their way through Toronto’s downtown core to lay siege to the legislature at Queen’s Park. One such militant demonstration culminated in a police riot on 15 June 2000. The post-mortem recorded 42 cops injured, and a like number of protesters arrested, including three of OCAP’s leading organizers. Court appearances involving over 250 criminal charges dragged into 2002-03, severely curtailing OCAP’s capacity to defend the poor, promote the need for affordable housing, and service and advise the disadvantaged who had come to depend on its expertise and aid. Allan Gardens continued to be OCAP’s rallying place of choice, and a 2011 protest of cut-backs to welfare rates by the government of Liberal premier, Dalton McGuinty, attracted 700. A barbecue sponsored by OCAP and the Canadian Union of Public Employees fed 1,000 as they gathered under a banner scripted out of 1930s protests: “United We Eat. Divided We Starve.”

Today OCAP is largely gone, but its spirit, and that of its militant predecessors remains. Allan Gardens continues to be a space where protest is nurtured and the poor and dispossessed gather. Tent encampments of homeless people remained long after the anti-poverty organization’s demise. Many of the unhoused were Indigenous. The city of Toronto eventually found accommodation for many of those living in Allan Gardens, and encampments, for the moment, are no longer set up in the park, although an Indigenous woman does continue to live there in what has become an iconic teepee, maintaining a sacred fire. Private security forces patrol Allan Gardens, making sure no new tents go up in a park that has recently seen extensive renovations to a pavilion that authorities obviously want to attract tourists and respectable visitors. Throughout Toronto, however, homelessness remains a central and troubling issue, with many people forced to live in ravines and other public spaces.

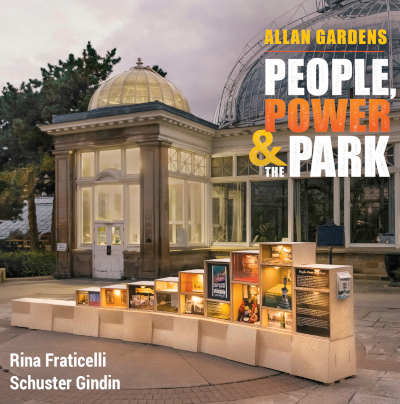

In September 2022, a four-day festival of music, poetry, dance, and ceremony marked the artistic installation of a 27-tableaux 23-foot-long sculpture. The revelry and creative paneling were part of a long-term project led by cultural programmer and filmmaker Rina Fraticelli and photographer and curator Schuster Gindin. The installation utilized storytelling, artistic representations, documents, and other cultural/political materials to commemorate the 130-year history of Allan Gardens. Fraticelli and Gindin aimed to build a sense of community development over time. Two years later, they put out a wonderfully illustrated volume, Allan Gardens: People, Power & the Park. It documents how Allan Gardens has long been a public venue where freedoms of association and expression are fought for and preserved, establishing the continuity of working-class and Indigenous protest under capitalism and colonialism.

In Allan Gardens, a horticultural park originating in an act of colonial dispossession transitioned to privatized property. This public space was then fought over by generations of dissidents. They demanded the right to be heard. In doing so, they voiced criticisms of a society that justified inequality and rationalized oppression, exploitation, and repression. Within the public space of a park, the intersection of race, gender, and class was lived out in the struggles of Indigenous and racialized peoples, of women and sexual minorities, and of workers, waged and unwaged. A place created as an expression of elite sensibilities was remade into a visible reminder that the struggles of the dispossessed can never be entirely suppressed. •

To Learn More:

- Rina Fraticelli and Schuster Gindin, Allan Gardens: People, Power & the Park (Toronto: King’s Road Press, 2024).

- Bryan D. Palmer and Gaétan Héroux, with a foreword by Francis Fox Piven, Toronto’s Poor: A Rebellious History (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2016).

- Gaétan Héroux, “Poor People’s History of East Downtown Toronto” (Toronto: LeftStreamed, 2014).

- Joan Sangster, One Hundred Years of Struggle: The History of Women and the Vote in Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2018).

- Donald B. Smith, “The Dispossession of the Mississauga Indians: A Missing Chapter in the Early History of Upper Canada,” Ontario History, 73 (June 1981), 67-87.

An abbreviated version of this essay was commissioned for the “Workers’ Memorial Sites” section of the Brazilian website, Laboratório de Estudos de História dos Mundos do Trabalho, where it appeared October 2025.