BRICS: A Defensive Coalition Against the Empire

The decline of the United States is the main explanation for the rise of the BRICS and allows us to place the dynamics of this emergence in a long-term context. It is important to precede any judgments on the expanded quintet with this diagnosis in order to avoid simple praise or condemnation of an alliance that is representative of the new multipolar scenario (Wolff, 2024).

The BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) have formed a coalition to set their own agenda, in opposition to Washington’s dictates. They aspire to act independently of these demands, following the weakening of US imperial power. They operate as a defensive bloc, resisting submission to the geopolitical and economic mandates of the leading power (Halas, 2024).

The quintet forms a distinct alignment within the dominant imperial system and has all the characteristics of a non-hegemonic alliance. This status does not in itself imply the presence of a counter-hegemonic actor with alternative projects.

Some analysts consider that containing US military aggression is the main function and greatest current merit of the BRICS. They deduce from this role that the enlarged group plays a progressive role in the contemporary context (De Sousa, 2024). This assessment is based on basic principles of a leftist view of geopolitical dynamics. By containing imperial militarism and weakening its incursions, the BRICS contribute to improving conditions for popular struggle and the achievement of gains.

They do not themselves provide remedies or solutions to the ills of capitalism, but by clashing with the imperial foundations of that structure, they facilitate a more favorable environment for fighting against that system (Patnaik, 2023).

Bandung and the Non-Aligned

The BRICS do not form an anti-imperialist bloc, such as the one formed in 1955 at the Bandung Conference. The contrasts with that precedent are enormous, and the expanded quintet (new members include Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates) itself rejects any familiarity with its precursor. It is important to note that none of its members identify with that pioneer, in order to avoid forced comparisons (Prashad, 2023a).

One need only compare the composition of the current BRICS leadership with the leadership that headed Bandung to confirm the monumental distance that separates the two organizations. Putin, Lula, and Ramaphosa have no kinship with Nehru, Nasser, and Zhou EnLai, and Modi and Bolsonaro were diametrically opposed to those figures. The fact that far-right presidents are able to keep their countries within the BRICS during their terms in office illustrates the impressive political plasticity of that bloc.

The direct complicity with Israel of new members – such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt – is also indicative of the organization’s profile (Bond, 2025). None of this collusion with imperialism had any place in Bandung.

That conference was an emblem of the Third World, and all its participants shared the peripheral-dependent status of their economies. That homogeneity is currently absent from the BRICS.

There, a central power (China), which disputes world supremacy with the United States, coexists alongside several semi-peripheral partners, which maintain enormous productive distances between themselves (Russia and South Africa). The bloc also includes typical exponents of the periphery (such as Ethiopia). For this reason, there are classic relations of dependency between the BRICS members themselves (China sells manufactured goods and buys raw materials from Brazil), which were not present in Bandung (Delcourt, 2024).

The BRICS do not constitute an anti-imperialist alliance, and it makes no sense to force this characterization in order to praise or denigrate their initiatives. Any assessment of the progressive or regressive nature of their actions must be based on a different diagnosis.

A comparison between the BRICS and the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) reveals certain features that are worth noting. Although the NAM was formed in 1961 at the height of the Cold War – with programs of neutrality in the confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union – it adopted, in practice, a profile of resistance to US military aggression. Due to its good relations with the socialist bloc and the serious conflicts that separated it from the West, it offers elements of similarity with the BRICS.

The MPNA (Movimiento de Países No Alineados, Non-Aligned Movement) included a wide range of ideologies, contained governments of divergent political persuasions, and prioritized the economic agenda. It emerged at the same time as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) was being formed, with the aim of supporting the development of the periphery by questioning the demands imposed by the centers.

The similarity with the BRICS lies in the commercial origins of this bloc, which emerged in a dispute over patent payments in the WTO negotiations. This gesture of autonomy led to developmentalist policies that connect the new quintet with the old Non-Aligned Movement.

In the first decades of the 21st century, the same debates on industrialization in Asia, Africa, and Latin America that prevailed in the middle of the last century have reappeared. This discussion is different from the past, and the neo-developmentalist projects in vogue differ from their predecessors, but the theme is similar and inspires all the economic initiatives of the BRICS (Katz, 2015: chap. 7).

Anti-Imperialist Reappraisals

It is important to recognize the qualitative differences that separate the BRICS from Bandung in order to avoid naive or nostalgic reasoning (Prashad, 2025a). The parallels that can be drawn with the “spirit of Bandung” are merely political and educational messages, pointing to goals, aspirations, or projects. They do not imply diagnoses of the current reality of the quintet. The difference between the two references is very significant and invalidates analogies, but the comparison provides ideas for a program or future development (Prashad, 2025b).

The emergence of the BRICS allows, above all, to clarify, reclaim, and disseminate the Bandung legacy as an anti-imperialist tradition that is highly relevant for the left today (Bruckmann, 2018). It serves to highlight a forgotten event, after several decades of neoliberal pre-eminence and counterrevolutionary offensive, that have sought to bury the great milestones of the struggle on the periphery against the imperial oppressor.

The impact of Bandung was very present throughout the period of uprisings and wars that marked decolonization. It established a type of social demands and development requirements that contributed to promoting, for example, the call for a New International Economic Order (NIEO) in 1974.

That stage came to an end with the implosion of the Soviet Union and the extinction of the so-called socialist bloc, but the resurgence of progressive and radical projects – in direct opposition to the current wave of the far right – requires a recovery of the legacies of the left. Bandung is an important part of that memory.

No one can seriously imagine the conversion of the current members and governments of the BRICS into an extension of Bandung. To discuss such a mutation is a simplification by the bloc’s apologists or a disqualifying argument by the denigrators of that alliance. What is at stake is the existence of a favorable opening to fight for that perspective, with other actors, other subjects, and other programs than those currently prevailing in the BRICS.

In an approach to this course, some analysts highlight that the quintet has changed the balance of global forces without modifying the general content of that scenario. It disputes the current system without disrupting or transcending it (Prashad, 2023b). But its emergence introduces fractures at the top that did not exist during the zenith of globalization, and this erosion creates opportunities to recover the popular project.

Taking advantage of these new conditions to rebuild the left involves multiple and controversial paths, but it presupposes, above all, recognizing the differences that separate the BRICS from the enemy led by the United States and its partners (Desai, 2024).

Recognizing that these two blocs are not equivalent is the starting point for any reflection on the connections between the BRICS and Bandung. That conference was a milestone in the battle against US imperialism, which is highly relevant in the current century.

The Socialist Project

The Bandung references for assessing the current context are also important to remember what was missing from that conference. It was a milestone in the resistance against colonialism and imperialism, but the social objectives of eradicating inequality, oppression, and exploitation – formally set out by many leaders at that meeting – were frustrated by the continuity, reinforcement, or remodeling of capitalism.

This is the main negative lesson of that experience, which drives us to reformulate that project as anti-capitalist objectives. The “spirit of Bandung” can only be successfully realized if it is rethought as a socialist horizon.

It is important to remember this unfinished business in a year that marks not only the 70th anniversary of that conference, but also the 50th anniversary of the fall of Saigon and the triumph of the revolution in Vietnam (Bello; Guttal, 2025).

The socialist reformulation of the Bandung goals is also relevant to the counterpoints currently being established with the BRICS.

All of that association’s pronouncements in favor of development and equity are laudable objectives, the realization of which is irreconcilable with capitalism. It is worth remembering that incompatibility in the face of the barrage of analyses that presuppose the endurance of that system.

Those views tend to argue that the current scenario is just another episode in the perennial mutation of that regime. But they forget that capitalism was seriously questioned during the financial collapse of 2008. The very existence of the BRICS today is largely due to the survival of that system.

Radical Initiatives

On the left, there is debate about whether the BRICS can implement initiatives that favor the people, or whether, on the contrary, these achievements require battles outside that framework.

The controversy takes into account that the majority of right-wing, conservative, or center-left governments that predominate in the group are enemies of these improvements, reluctant to grant them, or powerless to implement them. But it also notes the difficulty of achieving these advances, ignoring the central role played by the states that are part of this association. This dilemma can be resolved by developing programs that support popular demands and by building organizations to achieve them.

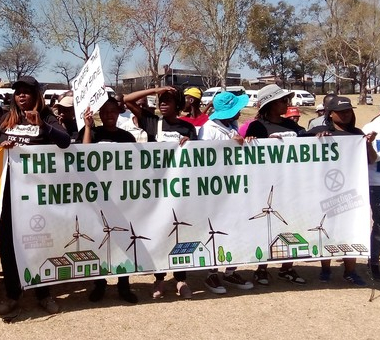

This old formula for political action applies to the BRICS. As they form a distinct bloc in conflict with the dominant imperial system, they must be the target of social, democratic, and political demands from popular movements. These demands overlap and reinforce the same claims that are heard at the national level within the association.

There are already many examples of such coordination, and the BRICS’ own history has been marked by social forums organized to coincide with the annual summits. The “BRICS from below” assemblies held at several of these meetings are examples of this approach (Bond, 2013). There, the same types of “People’s Summits” were organized, which have accompanied many official UNASUR or CELAC meetings in Latin America.

Palestine occupies a central place in the demands emerging for the next BRICS conclave. Two members of the quintet have denounced Netanyahu’s crimes. The South African government is pushing for effective sanctions, and its Brazilian counterpart is crying out against the massacres and murder of children by starvation. A petition is already circulating calling on Lula to break off relations with Israel (Infobae, 2025), which should be extended to all governments at the Rio Summit.

In this regard, there are echoes of Bandung, because the struggle against South African apartheid was a symbol of that conference. Zionism is the obvious continuation of that racist colonialism, and the battle against its crimes is the main democratic banner today.

Approving Views

Many laudatory views of the BRICS present this bloc – in its current configuration – as an alternative to the historical dominance of the West. They highlight the attraction it generates among countries affected by this dominance and emphasize the steps the group is taking to become the promoter of a new multipolar world.

However, this description merely extols the quintet’s differences from the current order, without clarifying its actual role. To claim that it constitutes something different from the prevailing system does not clarify what this novelty consists of. Along the same lines of mere portrayals is the exaltation of the group as a power structure opposed to its Western competitor.

These observations are more promising when they highlight the presence of a dispersion of power (multipolarity), which has allowed the emergence of a counterweight to the imperial system. This emergence weakens the ability of the main oppressors to subjugate the bulk of the population. In this regard, the mere emergence of the BRICS is a promising development, but it is totally insufficient to bring about significant changes in the prevailing order.

The bloc is also praised for the culture of coexistence it introduces within the alliance among countries with diverse traditions, religions, and cultures (Garzón, 2024). In other views, this cohabitation is interpreted as a sign of the “de-Westernization” that is emerging in the 21st century, in close harmony with the decline of the United States, the stagnation of Europe, and the rebirth of Asia. The BRICS are perceived as an expression of the “post-American world” in the making (Vignolo, 2023).

But this long-term view leaves unanswered the question of what benefits the expanded quintet would bring to the exploited and oppressed of the world. It correctly points out that it is emerging as a power in dispute with the main oppressors of the dispossessed, but it does not clarify to what extent or in what way it would contribute to reversing the suffering of these majorities.

To consider this possible connection, we must overcome the naive idealizations of the BRICS, remembering above all the influence that ultra-right-wing governments (India), despotic monarchies (Saudi Arabia), brutal dictatorships (Egypt), and authoritarian regimes (Russia) have in the expanded quintet.

It is also necessary to specify to what extent this alliance promotes peace, détente, and the peaceful resolution of international disputes. It certainly acts as a defensive bloc against the imperial aggressions of the United States, Europe, and Israel. The BRICS do not promote the blockades, sanctions, or sovereignty violations promoted by the Pentagon, the State Department, and NATO (Elbaum, 2024).

However, each member of the alliance tends to engage in demonstrations of power to assert its primacy in its regional environment. They reject the interference and provocations of US imperialism, but they do not spare their own neighbors from abuses. India’s military aggression is only the most recent example of this bellicosity.

The idealization of the BRICS is often linked to the identification of this bloc with the Global South. As the actual meaning of this concept is so varied, it is difficult to pinpoint the meaning of this term for the quintet.

The two powers that command the BRICS dispute geopolitical and economic supremacy in the current order, from positions that are obviously far removed from the mere helplessness of the South.

It is as problematic to place the Russian giant as the Chinese colossus in the ranks of the world’s dependent countries. But it is also controversial to include regional powers such as India and Brazil, which have assumed a growing role among the middle economies, in the group of the underprivileged.

The internal heterogeneity of the bloc itself contradicts its mere location within the Global South, because if the latter concept refers to center-periphery relations, this asymmetry is very present within the BRICS. One need only look at the type of trade between China and Brazil to see the typical transfers of value objected to by ECLAC or Dependency Theory.

The BRICS have forged an association in the midst of a reconfiguration of the global division of labour. This reshaping is introducing major changes in the economic and geopolitical position of each country on the world stage. There is as yet no comprehensive concept of the “Global South” that can be applied to the group, and simple class classification (capitalists-wage earners) does not clarify its effective status either.

The BRICS bloc of two dominant powers (China and Russia) associated with the main intermediate actors (Brazil, India, South Africa) has now expanded with its new members to include rentier economies of global weight and peripheries with strategic locations. The conceptualization of this group is a pending issue that requires elaboration free from embellishment and idealization. •

This article first published on the Katz.lahaine website.

References

- Bello, Walden, Guttal Shamali (2025). “Reivindicar el espíritu de la Conferencia de Bandung de 1955,” 11/05/2025.

- Bond, Patrick (2013). BRICS in Africa: anti-imperialist, sub-imperialist or in between?

- Bond, Patrick (2025). “Both the BRICS and Bandung revivalism need tough critiques – not quasi-cults.”

- Bruckmann, Mónica (2018). “América Latina y la nueva dinámica del sistema mundial,” 31/07/2018.

- Delcourt, Laurent (2024). BRICS y África: ¿nueva alianza win-win o colonialismo newlook?

- Desai, Radhika and Ben Norton (2024). “How can BRICS de-dollarize the financial system?” 24-11-03.

- De Sousa Santos, B, (2024). “Tercera guerra mundial, los BRICS y la salvación del planeta,” OtherNews, 3 janvier.

- Elbaum, Jorge (2024). “Los BRICS y el ocaso de Occidente,” 2024-10-13.

- Garzón, Aníbal (2024): “Today, the Global South sees the BRICS as the only alternative to a different world order.”

- Halas, Garrett (2024). “Multipolarity, BRICS+ & Socialism. Theorizing the Global Class Struggle,” Aug 22, 2024.

- Infobae (2025) Intelectuales y congresistas brasileños le piden a Lula romper relaciones con Israel.

- Katz, Claudio (2015). Neoliberalismo, Neodesarrollismo, Socialismo, Batalla de Ideas Ediciones, Buenos Aires.

- Patnaik, Prabhat (2023). Behind BRICS Expansion, September 4.

- Prashad, Vijay (2023a). On BRICS and Why Global South Cooperation Is Key to Dismantling Unjust World Order.

- Prashad, Vijay (2023b). “The BRICS Have Changed the Balance of Forces, but They Will Not by Themselves Change the World,” August 17, 2023.

- Prashad, Vijay (2025a). Resurrection, Moats with George Galloway, Ep 440, 19-4-April.

- Prashad, Vijay (2025b). El “espíritu de Bandung” y el desarrollo industrial de Indonesia, nuevo miembro de los BRICS+ 16 abril.

- Vignolo, Walter (2023). “Argentina. Los BRICS y el G-7.”

- Wolff, Richard (2024). “BRICS Breakthrough? Economists Richard Wolff & Patrick Bond on Growing Alliance, Challenge to US,” October 25, 2024.