Hard Questions for Portugal’s Left Bloc After a Terrible Parliamentary Election

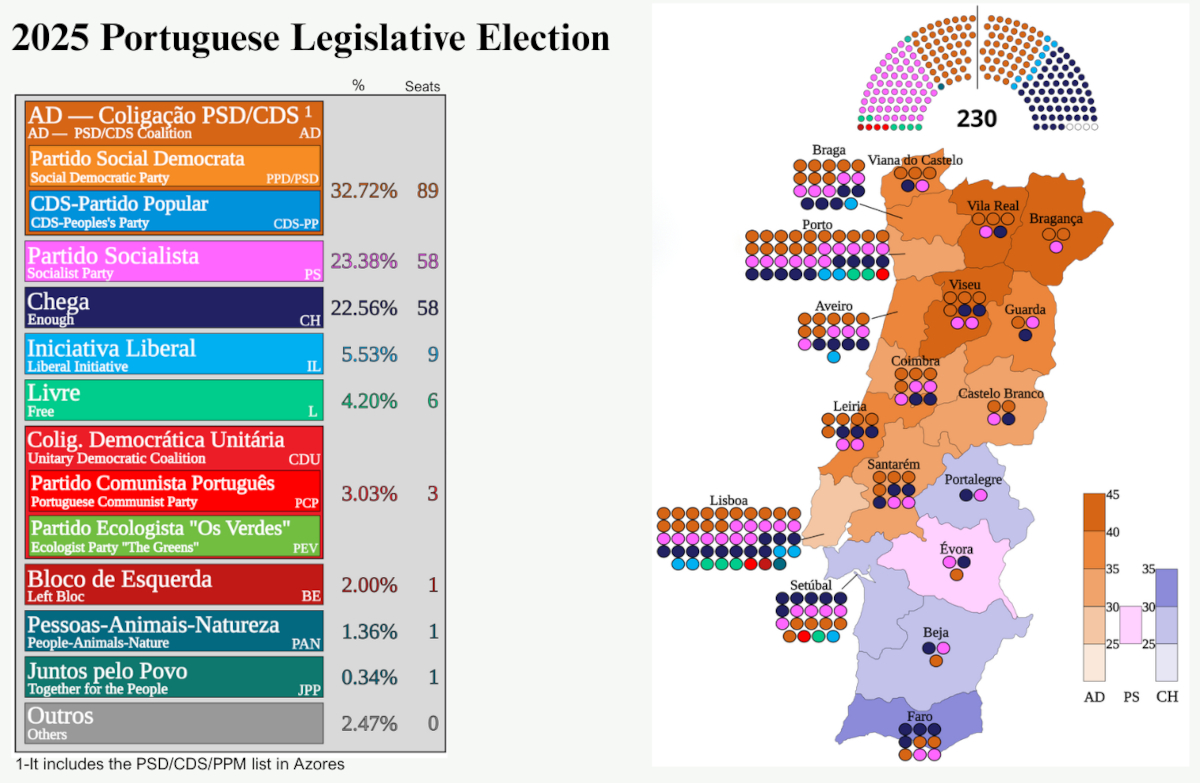

The 18 May parliamentary elections were a disaster for Portugal’s Bloco de Esquerda (Left Bloc). The far right replaced the Socialist Party as the main opposition to the conservative government, and may now push for constitutional changes. All left parties suffered but none as much as the Left Bloc. Its vote collapsed, and it lost 4 of its 5 seats in the Assembly of the Republic (parliament). In this National Board resolution, the Left Bloc leadership takes stock of the legislative election results, starting from the national context and the party’s campaign, to find answers for the future. — Adam Novak

The Left Bloc has achieved its worst result in its history in elections for the Assembly of the Republic. The Bloc faces these results with concern and intends to carry out an assessment that allows it to correct mistakes made, listen to all factions and also independent people, in order to develop an orientation that guarantees the effectiveness in the future of this political project, its social intervention, and its alternatives. This process is not done hastily nor by finding a single explanatory factor. It requires time, humility, openness, and availability to find paths that we will only discover collectively.

The total number of votes for parties to the left of the Socialist Party (PS) is the lowest ever, and the same applies when this amount includes PS. These defeats – of the left as a whole and of the Bloc – place the country at grave risk. To understand the consequences, it is necessary to study the factors that determined the electoral disaster, as well as what is specific to each political factor. This examination discusses some national and international political constraints and their impact, particularly the Prime Minister’s strategy, the effect of transforming immigration into the centre of political debate, and also the fear of war. It also begins a reflection on our campaign.

The Election Context

The political crisis created by the Prime Minister following the violation of his exclusivity duties was a manœuvre with precedents in recent governance that contributed to the degradation of the political environment. It proved successful for Montenegro, allowing him to recover his capacity for action. The first indication, in the sense of accepting a constitutional revision with Liberal Initiative (IL) and Chega (CH), even if cloaked in a declaration about open availability, is an undisguised and extremely serious threat against some of the pillars of April’s democratic achievements.

The move to the centre of political debate of the immigration theme was an important factor in the left’s failure. Portugal has suffered one of the most profound transformations in its social composition and working-class profile. In just a few years, the number of foreign workers multiplied tenfold and corresponds to about a third of the active population. A relevant segment of this new working class does not come from Portuguese-speaking countries. In this context, the failure of service in general including regularisation services and the disinvestment in comprehensive responses in the areas of housing, public services, and language access enhanced the far-right narrative. The resulting deterioration of the workers’ life circumstances was then adopted by the government in justifying new legislation that was also legitimised, secondarily, by PS’s retreats in these matters. This narrative was popularised by the sensationalism of some media outlets and especially by mass manipulation through social networks. In fact, the far-right managed to transform immigration into the explanation for the entire population’s life difficulties, from housing to hospitals.

The Bloc and other parties were penalised in the vote as a consequence of this reality. The lesson is that anti-racist and anti-fascist militant action continues to be essential as is the creation of common and unitary spaces and intervention in areas disputed by authoritarianism and hate speech. It is crucial to find ways to open trade unions to foreign workers, to create inclusion mechanisms, to prevent the exploitation of differences to promote social resentment. The fight against the division of the working class is essential today as well as tomorrow.

Trump’s re-election has several consequences for international politics, which boost the far-right: firstly, it promotes genocide in Gaza and makes Netanyahu unassailable to international pressure, antagonising governments that denounced Palestinian genocide, such as South Africa’s; secondly, it seeks an alliance with Putin; thirdly, it promotes a reactionary international element that directly involves the American administration in German and other European countries’ elections; fourthly, it uses tariffs as an economic policy to foster submission of its allies and partners, and confrontation with China.

In this international context, the Left Bloc identified the risk of accentuating the rightward turn of the past year, particularly under increased militarist pressure in this new framework. This pressure creates fear and displaces politics to the right, leading centre parties to accept the European arms race and submission to NATO.

These three factors – AD’s (centre-right alliance) gambit, which adopted the discourse on stability that gave PS an absolute majority in 2022; the centrality of the immigration question defining all national politics; and fear of militarist propaganda – were determining factors in the general election context.

The Immediate Response to the Constitutional Threat

The greatest transformation that occurred on 18 May was Chega’s growth. This result demonstrates its capacity to maintain the electorate it recovered from obscurity in 2024, increasing it throughout the territory, particularly in more socially depressed areas, interior regions, and former industrial belts. Predictably rising to second place in the number of deputies (should the counting of emigration constituency votes conclude thus), Chega effectively begins to dispute government. This new situation will translate into a general degradation of democratic conditions, both in parliament (where Chega has conducted a strategy of exhausting debate and expressing conditions for several years) and in society, with the trivialisation of racist, sexist, transphobic, and homophobic violence and, generally, fascist violence. By becoming the majority in the south of the country and in Setúbal, and by reinforcing its vote in all districts, the far-right gained popular votes, including many that were previously represented by left-wing forces. With this representation, Chega will aggravate its xenophobic and anti-democratic campaign, articulated with the action of criminal groups moving in its periphery (see the recent attack on the 25 April demonstration by a neo-Nazi gang, immediately applauded by Chega).

In the new parliamentary composition, none of the three largest parties can form a majority with smaller parties. However, for the first time, parties to the right of PS exceed the two-thirds threshold that allows them to promote constitutional changes. This fact becomes central in the present political situation, configuring a real risk of regressive alteration of the constitutional regime, considering PSD’s history in this matter, both in the attack on pensions under the troika, and in proposals for electoral law revision, or in recent declarations about the right to strike. IL and Chega have already announced their intentions. The Left Bloc considers essential the united expression of all voices and political forces that see themselves in the values and text of the 25 April Constitution, in defence of the freedoms and guarantees it enshrines.

For the Bloc, the objective is not only to resist the fascist and xenophobic wave or possible and dangerous conjugations of the right and far-right, or PS support for Montenegro’s governance. The Bloc’s objective is to rise again, recover, create and broaden alliances, and fight for our people with determination.

The Bloc’s Campaign

In the new political circumstances, we revised our campaign model. Thus, we decided to focus on a few essential themes to which we gave the greatest prominence, seeking to dispute public debate: rent caps, rights of shift workers, and tax on the rich. We did not abandon other programmatic battles that make the Bloc’s identity, such as public services, equality, rejection of xenophobia, or opposition to war, but we concentrated on those essential themes so they would be our brand to avoid empty discussion about governability, pointing to measures that would allow life changes for significant parts of the population and topics our parliamentary representation would dispute in any circumstance. This policy was effective: the rent caps question was important in political debate, forcing all our adversaries to announce themselves, was reinforced by increasingly alarming news about the housing crisis, and was identified by part of the population as a valid response. It will continue to be one of the most important fights for our people’s lives – even the majority of working families who buy their own home know that their children will not be able to do so, nor even rent a house. The second proposal, about shift work, was supported by thousands of workers. However, neither led to electoral recovery in the context described above.

Secondly, our campaign favoured decentralised initiatives of direct contact through door-to-door campaigning. We went to more than twenty thousand homes and initiated a form of political action that will be fundamental in the future. We did this in a differentiated way across the country, mobilising young militants, recent and older adherents, who verified how they could intervene directly and not as spectators of the electoral campaign. For the same reason, we replaced traditional rallies with “coffee conversations,” open to dialogue with everyone, and with creative and animated parties and public sessions.

Thirdly, we mobilised all our forces, including the candidacies of the party’s founders. These candidacies had no electoral effect but did have militant effect, energising campaigns in larger districts.

These choices did not reverse our electoral cycle, and the Bloc suffered its worst defeat. And, knowing that discussion about the election assessment will allow for identifying errors and will benefit beyond the specific questions, communication models, forms of organisation, campaign pedagogy, adequacy of responses to dirty campaigns, or other aspects of this battle, the Bloc affirms that it will not stop fighting for what we took to these elections: for a popular housing policy, for workers’ rights, against inequality and for quality and guarantee of public services, against fascist threats, and for unity in defence of democratic life and the constitutional rules that protect it.

Deliberations

On 13 and 14 June, in Porto, the Left Bloc will hold the founding congress of the European Left Alliance for People and Planet, a new European political party that brings together Left Bloc (Portugal), La France Insoumise (France), Left Alliance (Finland), Podemos (Spain), Red-Green Alliance (Denmark), Razem (Poland) and Left Party (Sweden). The advance of far-right forces and the increase in social, environmental, and international crises require more effective cooperation of green, feminist, and an anti-racist European left. The Left Bloc commits to this new alliance and invites adherents and sympathisers to active participation in this moment of debate and learning. In this congress, open to participation of other left forces, European and international, and to movements and social activism, we intend to create new forms of solidarity work and prepare concrete mobilisation actions against capitalism and against war, resistance to the far-right, and recovery of social majorities on the left.

The Left Bloc will continue preparing its candidacies for local elections, reaffirming its commitment to policies for left convergences, whether these are with PS in Lisbon to defeat Carlos Moedas, or support for local left alternatives. Even in councils where the Bloc has already presented candidacy, it maintains its availability for new affiliations, whenever possible, with PCP, Livre, PAN and citizen movements.

Given the numerous youth supporters verified throughout the electoral campaign and in days following the elections, the National Board reiterates its appeal for participation in Freedom Camp, which will take place in the centre of the country from 24 to 27 July. This and other major meetings for political cooperation and debate, such as Socialism 2025, which will take place from 29 to 31 August, are critical in this new phase of the country’s life.

In face of the new political situation and the Bloc’s heavy electoral defeat, the National Board has decided to launch a new National Convention call for 29 and 30 November. This is, therefore, not about resuming the process that was suspended due to elections. Given the change in national political circumstances, the need for profound reflection and definition of an orientation for coming years. This could not be treated as mere conclusion of a process initiated in January 2025, when legislative elections were not even imagined and Trump had not taken office. With this decision, a new period opens for presentation of orientation motions, and the roster of supporters with the right to elect and be elected is updated. •

This article first published in English on the Europe Solidaire website.