Culture as a Pedagogical Battlefield in the Fight Against Authoritarianism

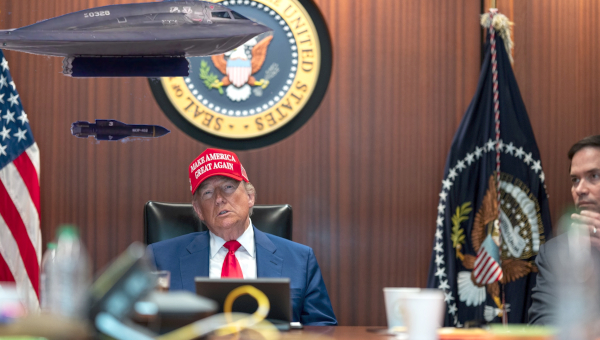

On June 6, resistance ignited in the streets of Los Angeles to confront the Trump regime’s brutal campaign against immigrants, enforced by the brutality of United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents and the machinery of mass deportation. In a chilling escalation, Trump branded the protesters “insurrectionists” and threatened the use of military force – turning dissent into a crime and protest into a pretext for repression. Stephen Miller, White House deputy chief of staff, called Los Angeles “occupied territory,” adding, “We’ve been saying for years this is a fight to save civilization.”

This is not merely the rhetoric of strongman fantasies; it is the language of fascist ambition, a calculated pretext to invoke the Insurrection Act and erect a police state. Beneath this chilling facade lies something far darker: the weaponization of the war on immigrants as a means to orchestrate ethnic cleansing, veiled under the apparatus of law and the grotesque spectacle of state power. Moreover, as Christie Noem and Trump have blatantly outlined, their assault on immigrants extends beyond individual lives, it’s a direct attack on America’s largest cities, like Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York, which stand as Democratic Party strongholds. When they claim to be liberating these urban centers from “socialists,” they are not just declaring war on ideological foes, they are setting the stage for a fascist takeover, one rooted in division and destruction.

Rise of the Police State

This is not about upholding law and order; it is the calculated weaponization of authoritarian culture to escalate state violence, instill terror, criminalize dissent, and legitimize white nationalist ideology. By framing defiance as treason, Trump attempts to cloak his own authoritarian crimes while constructing a political climate where any challenge to power is met with brutal retaliation. As Michelle Goldberg noted in The New York Times, “This is what autocracy looks like.”

The authoritarian dream is rooted in the belief that state violence should serve as the primary tool of governance. When the guardrails of democracy are dismantled, violence shifts from being a last resort to a governing principle. This is precisely what unfolded in Los Angeles, where Trump deployed the National Guard and Marines to crush protests against his mass deportation policies, while mobilizing ICE as a modern-day Gestapo. What cannot be ignored is that the militarization of civil society is not merely an overreaction or illegal response to a fabricated insurrection; it is the very foundation upon which martial law is established, paving the way for a fully realized fascist state. What unfolded in LA was not an insurrection; it was the people rising in defense of democracy. The true insurrection happened on January 6, with Trump as its chief architect. Yet once again, violence was being used not to protect democracy but rather to crush it.

What we are witnessing is a spectacle of domination. The deployment of troops, the vigilante targeting of Democratic lawmakers, the planned grotesquerie of Trump’s military parade, and Trump’s order for ICE to target cities led by Democrats are not isolated events – they are scenes in the same authoritarian drama. Together, they represent a fusion of militarism and national identity, designed to normalize cruelty, fetishize strength, and recast obedience as patriotism. As Susan Sontag once warned, fascism cloaks violence in the aesthetics of spectacle, making submission not only palatable, but seductive. This is the pornography of power – where culture and repression merge in a theater of fear, scripted to extinguish political imagination and render dissent illegible.

In this moment of escalating violence, Trump’s use of force is more than a show of control – it is a pedagogical performance meant to normalize repression and etch it into public consciousness. This is fascist aesthetics reimagined for a media-saturated age, where power must not only be wielded but displayed as performance. Here, domination is choreographed, televised, and turned into a civic lesson. The spectacle becomes a tutorial in submission, transforming images of state violence into instruments of mass indoctrination. Culture is not summoned to illuminate reality but to obliterate it, replacing historical memory with myth, dissent with loyalty, and resistance with silence. The convergence of Trump’s militarized crackdown in Los Angeles and his self-aggrandizing parade of force reveals a machinery of destruction no longer hidden but flaunted, a grotesque exhibition engineered to numb the senses and turn state terror into a national ritual.

The Terrain of Culture Is Central in the Struggle Against Authoritarianism

In the current political moment, we would do well to remember Milan Kundera’s words from The Book of Laughter and Forgetting:

“The first step in liquidating a people is to erase its memory. Destroy its books, its culture, its history. Then have someone write new books, manufacture a new culture, invent a new history. Before long the nation will begin to forget what it is and what it was.”

Indeed, dominant culture is not peripheral to politics; it is its staging ground, its arsenal, and, increasingly, its most contested terrain. Authoritarianism does not rely solely on law or policy; it reshapes consciousness, manufactures consent, and weaves the logic of domination into the fabric of everyday life. Under Trump, culture is not merely an accessory to power – it is the weapon and the war zone.

Democracy is not shattered only by the blunt force of military coups; instead, it can be hollowed out from within, undermined by the ghosts of past tyrannies reanimated through symbols, digital technologies, and the ever-churning machinery of social media. Today, power speaks in the seductive language of images laced with bigotry, seeded with cruelty, and driven by the logic of exclusion and ethnic cleansing. Culture is no longer merely a reflection of the past; it has become its erasure. It functions as pedagogy – through what Ariella Aïsha Azoulay names as “imperial technologies,” and what I have called “disimagination machines.” It is designed to strip the colonized not only of their futures but also of their histories, their very presence in the world. In this age of resurgent fascisms, we see its devastating effects in the genocidal assault waged by Israel against the Palestinian people, and in the scorched-earth war on historical memory and civic belonging carried out by the Trump regime in the United States. Culture is no longer a backdrop to political struggle – it is its very stage, its arsenal, and its battleground. Culture as an educational force is no longer subordinate to relations of power – it is the very essence of politics.

As Catherine Caruso points out in Harvard News, “AI-powered autonomous weapons represent a new era in warfare and pose a concrete threat to scientific progress and basic research.” Yet the danger extends far beyond the battlefield. Artificial intelligence now plays an insidious role in shaping policy, normalizing militarism, censoring ethical debate, and legitimizing what can only be described as a culture of war. It reconfigures not only how we fight but how we think – molding public consciousness in ways that privilege surveillance over solidarity, control over compassion.

For instance, the rise of artificial intelligence is accelerating a cultural transformation that is as dangerous as it is seductive. When OpenAI recently shut down its ChatGPT responses on the Gaza war for ‘safety’ reasons, it wasn’t a glitch – it was a warning. AI is not just organizing knowledge; it is curating memory, defining what can be said, and erasing what must be forgotten. In the wrong hands – and increasingly in the hands of authoritarian regimes and corporate overlords, – AI becomes a weapon not of innovation but of ideological control. Brett Wilkins reports in Common Dreams that “commercial AI models are directly being used” by Israel in Gaza for mass surveillance and the targeting of “critics, dissidents, and opponents.” Culture, in this context, is no longer merely shaped by human struggle and historical memory; it is engineered, automated, and sanitized.

Too many on the left have long overlooked a fundamental truth: The real battle against gangster capitalism and its updated fascist versions is not solely over policies or economies but over culture itself – over the values, desires, and everyday practices that shape how people see the world and their place within it.

Capitalism Is Not Merely an Economic System

Historically, some strands of Marxist and progressive thought have dismissed culture as secondary or irrelevant – a critique that scholar Judith Butler powerfully challenged in their 1997 essay. They argued that the left’s cultural focus was wrongly seen as abandoning the materialist core of Marxist politics, often accused of being “factionalizing, identitarian, and [narrowly] particularistic.”

Downplaying the role of culture is not just a tactical misstep – it’s a fundamental error. As Antonio Gramsci warned, all politics is pedagogical, and every exercise of “hegemony” is inherently an educational act. In a capitalist society, the power of education does more than repress critical thought and informed consciousness, it actively shapes and empowers. It creates subjects, molds emotions, and defines what we accept as sensible.

As Theodor Adorno argued, capitalism is not merely an economic system but a totalizing cultural force, shaping desire through the “culture industry” – reducing human experience to commodified clichés and reinforcing conformity through repetition and distraction. Raymond Williams insisted that culture is both ordinary and political, embedded in the everyday practices through which people live and make meaning. Like Vaclav Havel, he believed that, “the political is not independent of the cultural, but it follows it.”

In this view, politics follows culture because the culture is the terrain in which politics establishes itself, the framework through which individuals are shaped, and the force that reproduces societies in ways that sustain distinct political systems. Stuart Hall’s work is crucial here in illuminating how culture is the site where ideology takes root, where identities are formed, contested, and secured. As Bruce Robbins notes in a commentary on Hall, everyday life could not be separated from politics as a matter of lived experience, and culture could not be removed from “the political and economic structures that constrained it.”

This insight is particularly evident in Hall’s critique of neoliberalism, which he framed not merely as an economic system but as a comprehensive pedagogical project. For Hall, capitalism is not imposed solely from above; it is lived, felt, and reproduced from below, intricately woven into the intimate structures of daily life. This is especially clear in its insistence that the market be the template for all social relations, as epitomized in Margaret Thatcher’s toxic assertion, “There is no such thing as society.” Here, Hall lays bare how neoliberalism is not just an economic system but a lived ideology that governs personal identities and social interactions, framing the very essence of human connection as a transactional exchange.

One of the most astute commentators on the role of culture in the rise of the far-right and fascism is Richard Seymour, whose perspective profoundly intersects with Hall’s. Both thinkers recognize neoliberalism as more than a mere economic structure – it is a cultural and pedagogical force. While Hall emphasizes how capitalism permeates the most intimate spheres of life, reshaping identities and relationships, Seymour delves deeper into the psychological and cultural consequences of neoliberalism’s dominance. Seymour highlights how neoliberalism’s success in dismantling solidarity and fostering individualism has given birth to a society marked by profound alienation and social disintegration.

Seymour, like Hall, underscores the pivotal role of culture in fueling the far-right’s rise and deepening political violence. Drawing from Gramsci, Seymour explores how culture and circumstance, rather than just economic interests, shape societal attitudes. He argues that neoliberalism has not only made economic competition the governing logic of society but has also fostered a ‘paranoid system’ where the absence of collective solidarity breeds resentment, envy, and rage. In such an environment, the far-right finds fertile ground, exploiting the isolation and anxiety that neoliberalism cultivates. Individuals, stripped of their sense of belonging, are pushed into a vicious cycle of competition and distrust. As Daniel Trilling notes, in this discourse, everyone is a competitor, public goods are derided, public services are by nature corrupt “and inefficient, and welfare recipients will be regarded as freeloaders.” This is not only a recipe for loneliness, mass anxiety, a distrust of any viable notion of the social and political violence but also an utter hatred of any form of collective action, which is perceived as a threat rather than a source of strength.

Seymour’s conception of neoliberalism as a cultural project aligns with Hall’s view of capitalism as a force reproduced from below. Both theorists draw attention to the ways in which neoliberalism’s ideological apparatus infiltrates daily life, subtly shaping not just our behaviors and beliefs but also our very emotional responses to the world. In the ruins of neoliberalism, as Seymour suggests, the far-right’s ascension is not merely an economic outcome but a psychological and cultural one – rooted in the transformation of society into a fragmented, competitive terrain where individuals struggle to survive in the absence of any meaningful social sphere or collective support. Here, neoliberalism’s deep cultural influence becomes the soil in which the far-right’s dangerous ideologies take root.

Confronting the Current Dominant Culture of Cruelty

We are, in this Trumpian historical moment, suffocating under a dominant culture that functions as a powerful disimagination machine, shaping desires, identities, and common sense through a vast network of pedagogical sites, from social media and news platforms to advertising, entertainment, and relentless political spectacles. Education is no longer merely an institutional force; it has become the most decisive cultural arena where individual and collective consciousness is produced and contested. Hall understood this with prophetic clarity. For him, culture is never outside politics; it is the terrain on which political struggle is fought, particularly through the politics of identification.

Later in his life, Hall warned that the left had failed to grasp the educative dimension of politics, the need to transform not just policies but the very framework through which people interpret the world and their place in it. In a 2012 interview with The Guardian’s Zoe Williams, Hall put it bluntly: “The left is in trouble. It’s not got any ideas, it’s not got any independent analysis of its own, and therefore, it’s got no vision. It just takes the temperature: ‘Whoa, that’s no good, let’s move to the right.’ It has no sense of politics being educative, of politics changing the way people see things.”

For Hall, without this pedagogical imperative, the left forfeits its ability to generate hope, build alliances, and forge new political subjectivities. The promise of democracy is torn asunder. In the shadow of rising state terrorism, bodies are broken, abducted, and freedoms extinguished. Silence spreads like a fog. It blankets the cries of the young, the starving children of Gaza; lives obliterated by bombs and buried by indifference as entire families are killed by Israel in Gaza. The horror knows no borders, reproduced at home as immigrant youth in the United States are torn from their families, thrust into a trauma so vast it swallows the future.

Meanwhile, as Peter Baker notes in The New York Times, the demagogue-in-chief revels in gifts from dictators, ranging from a luxury flying palace from Qatar to collecting “$320-million in fees from a new cryptocurrency” and shamelessly brokering “overseas real estate deals worth billions of dollars.” Trump displays his vast corruption while openly normalizing the widespread abuse of presidential power. How else to explain his “opening an exclusive club in Washington called the Executive Branch [while] charging $500,000 apiece to join,” all the while presiding over a regime that slashes “funding for health care, food, and education through some of the largest cuts in US history, while even raising taxes on many low-income families”?

This is a Trump-Musk-engineered culture of cruelty, ramped up to grotesque extremes, a form of state terrorism that Bill Gates aptly describes as “killing the world’s poorest children,” both here and abroad. Beneath the surface, the agenda is clear: Trump’s budget, which he calls “one big, beautiful bill” is a deliberate weapon of mass inequality, ruthlessly crafted to fatten the coffers of the financial elite while punishing the most vulnerable. In addition, it has the “potential to increase the federal deficit by up to $3.8-trillion over the next decade.” This monstrous budget, born from the twisted minds of Trump and his MAGA sycophants, is so brutal that Paul Krugman condemns it as a product of “sadistic zombies,” a horrifying manifestation of cruelty that reflects the regime’s moral decay. His anger is rightly focused on a budget that slashes taxes for the ultra-wealthy while funneling endless resources into instruments of state violence, all in the name of control, domination, and the obliteration of any semblance of social justice, both within our borders and beyond.

“This is more than a policy crisis. It is a cultural catastrophe.”

This is more than a policy crisis. It is a cultural catastrophe. Fascism today is not only wrapped in lawless decrees and armed repression; it is also cloaked in spectacles of cruelty and a language steeped in hate and terminal exclusion. Trump’s fervent advocates, Elon Musk and Steve Bannon, raise Nazi salutes, as though rehearsing for the dark future they are determined to summon. Stephen Miller channels Hitler’s rhetoric under the guise of patriotism, declaring that “America is for Americans and Americans only.” Trump resurrects the Confederacy, embracing its monuments, symbols, and genocidal logic. In their hands, the culture of fascism is not hidden. It is performed, televised, and normalized. The horror of fascist violence is back, though it is now draped in AI-guided bombs, ethnic cleansing, and white supremacists basking in their project of racial cleansing while destroying every vestige of decency, human rights, and democracy.

What we are witnessing is the death not just of democracy but of moral and civic conscience itself. A collective numbness has settled in, a culture of forgetting, cruelty and complicity, where silence speaks louder than resistance, enabling the violence to grow unchecked. In part, this is fueled by an anti-intellectualism and culture that embraces civic illiteracy, a culture of immediacy that banishes informed judgment and contemplation, and institutions that embrace critical thought as a foundation for creating critical citizens. We are not merely talking about the death of the imagination but also an attack on any institutions that provide what Hannah Arendt once called “thinking without a banister.”

At the heart of this decay lies a cultural ethos cultivated by capitalism for decades: to live is to consume, selfishness is freedom, personal responsibility eclipses systemic problems, and solidarity is weakness. Culture has become a site of struggle, now more intense than ever, amplified by new digital technologies, social media, podcasts, and a host of other pedagogical platforms. These platforms not only disempower resistance but also amplify the forces of domination, shaping the contours of public discourse and ideological control. Society fragments further, social atomization rises, and the numbing routines of a consumer-driven spectacle are matched by what Jonathan Crary calls “vacant forms of attentiveness.”

Corporate-controlled cultural apparatuses now hold immense pedagogical and political power, reshaping the relationship between power, culture, and daily life. Everyday existence is captive to new modes of socialization, a tsunami of fragmentation, and the dissolution of society, driven by the morally numbing routines of a punishing state and its ever-expanding criminalization of free speech and social problems. In such a climate, the ideological mobilization of memory, agency, and desire becomes inseparable from the pedagogical construction of neoliberal public spaces and civic life, laying the foundation for an emerging authoritarianism.

Also central to this emerging fascism is a culture in which memory is rendered inaccessible, critical thinking is scorned, and dissent is branded as treason, subject to harsh penalties imposed by a regime of terror – one that includes abductions, attacks on due process, an unprecedented assault on higher education, and a growing political culture of corruption and lawlessness.

This isn’t to suggest that culture is simply absorbed into an all-encompassing system of domination, subjugated by the unchecked power of brutal billionaires and Vichy-like politicians. On the contrary, culture has moved to the front lines of struggle, central to the effort to normalize gangster capitalism, erase institutions that promote democratic values, and create an army of loyal fascist subjects. The vicious attacks by the Trump administration on higher education, public schools, journalists, oppositional media, and dissident politicians demonstrate the fear of Trump and his enablers who recognize the power of these institutions in potentially educating students and the wider public to hold power accountable, to engage in refusal rather than in conformity, adaptation, and political resignation.

At the same time, the right’s attacks have eroded the responsibility of institutions like Columbia University to stand against Trump’s assault on academic freedom and free speech. In failing to resist, they become complicit in what Chris Hedges describes as “capitulations and crackdowns on pro-Palestine activism,” resulting in the suspension, expulsion, and firing of students and professors protesting the genocide in Gaza.

In this context, as I recently stated in an interview on Courage My Friends podcast that critical education is the glue that connects hope, justice, and the fight for a real, radical democracy. If we fail to recognize the centrality of education, the left will be in serious trouble. But equally crucial is the need to rethink the power of culture as a site of both domination and empowerment, a site that holds profound pedagogical, economic, and political significance in the digital age.

Building a Culture of Solidarity

Cultural politics has a long legacy in Marxist thought, from Gramsci and Hall, to Robin D.G. Kelley, the Frankfurt School and the Situationists, to the radical movements of the 1960s and the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement. It’s time to reignite and propel this work forward, to shape it anew in the crucible of our present crisis and the urgency of this historical moment.

Late former Uruguayan President José Mujica, in one of his speeches, reprinted in Jacobin, argued poignantly “that capitalism is not just property relations but a set of cultural values that the Left must confront with a culture of solidarity.” He argued strongly that social change could not be reduced to changing capitalist economies and that “capitalism is a culture” with enormous power that must be understood, analyzed, and resisted. The late cultural critic Ellen Willis adds to this insight by noting that at the core of cultural politics is the recognition “that the project of organizing a democratic political movement necessarily entails the hope that one’s ideas and beliefs are not merely idiosyncratic but speak to vital human needs, interests, and desires, and therefore will be persuasive to many and ultimately most people.”

Mujica’s reflection on the limits of revolutionary strategy underscores the crucial role of culture in any transformative movement, emphasizing that without a profound shift in cultural consciousness, systemic change remains unattainable. This insight directly ties into the larger thesis that fascism cannot be countered merely through political and economic reforms but requires a radical transformation of culture itself, a cultural shift that challenges the very values and ideologies that sustain authoritarianism. He makes clear that struggles over culture are not just about struggles over meaning and identity but also struggles over power, human freedom, and equality.

Mujica’s lament is our warning. My generation, he said, made the mistake of believing that revolution meant taking over the means of production. Some of us thought we could change the system without changing the culture. But capitalism, he insisted, survives not through force alone but also through the everyday values it instills, values stronger than any army. You cannot build a new world with people shaped by the old one: “You cannot build a socialist building with bricklayers who are capitalists,” he warned, because their consciousness will reproduce the very system they seek to overthrow.

“If we are to reclaim democracy not as a slogan but as a living, breathing ethos, we must begin with culture.”

This insight could not be more relevant and urgent. If we are to resist the death cult of fascism, if we are to reclaim democracy not as a slogan but as a living, breathing ethos, we must begin with culture. Not the commodified culture of products and performances but rather culture in its deepest sense: the web of values, relationships, and meanings that shape how we live and what we imagine possible. We need, in short, a cultural revolution rooted in a politics of solidarity, care, limits, and humility. To be revolutionary today means more than redistributing wealth and changing economic structures, however fundamental. It also means redefining what it means to live well. It means teaching each other to resist the seductions of greed and the numbness of cruelty. It means building new ways of being together, of listening, of imagining. As Mujica said, “Poor is the one who needs a lot.” The left must reclaim a culture of enough, of sufficiency rather than excess, of cooperation rather than conquest.

Culture, as an educational force, does more than mirror society – it challenges dominant ideologies, unsettles normalized values, and disrupts the social relations that sustain oppression. It cultivates a critical awareness of how power operates, but awareness alone is not enough. Knowledge must ignite action. Critical consciousness must be bound to collective struggles – to movements that confront the machinery of poverty, the cruelty of inequality, the devastation of climate collapse, and the enduring violence of systemic racism. Without this fusion of insight and resistance, culture risks becoming reflection without consequence, critique without transformation.

The challenge for left progressives and others is to produce an anti-capitalist culture that provides the modes of literacy, comprehensive analysis, historical consciousness, and vision to make clear and resist a long legacy of colonialism with its fantasies of displacement, dispossession, and extermination. One cannot be silent or ignore a cultural politics in which Trump calls for a policy that amounts to the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from northern Gaza.

Trump’s neocolonial vision of an ethnically cleansed Gaza is not policy; it’s cultural imperialism draped in empire, a death wish spoken aloud, a nightmare clawing its way into daylight. The rigor mortis of ethical and political decay, born from colonial and imperial fantasies, is made even more visible by Trump’s call to annex Canada, Panama, and Greenland. Intoxicated with power, this resurgent view of globalization is fashioned on a toxic mix of greed, fear, delusions of grandeur, and cruelty. This is cultural politics in the service of death, a form of politics that not only perpetuates violence but also reshapes society in its own image, normalizing annihilation and dispossession as acceptable byproducts of imperial ambition.

There is no future without a cultural shift away from gangster capitalism. Without it, the left risks fading into a mere ghost, clinging to slogans while the world burns, as the politics of extermination, displacement, and ethnic cleansing rage on. The horrors of the past are back, but so too must be our memory, our imagination, and our courage to begin again – not as mourners of a failed nostalgia but rather as creators of a new, insurgent radical democratic culture. A culture that remembers the children, hears the silences, and refuses to let the future be stolen without a fight. The fight against fascism demands a new language, one that integrates materialist and cultural concerns, where the critique of structural domination is inseparable from cultural and educational struggles. This language must reshape how we think about power, justice, and agency, emphasizing the need for a critical pedagogy and cultural transformation that challenges the ideologies sustaining authoritarianism while empowering collective resistance.

In this struggle, pedagogy is not peripheral; it is the front line. Education, culture, and daily life are the terrains where fascism is either normalized or resisted. This is where mass consciousness takes root and where the seeds of a transformative political movement are sown. Despair is not an option; it is surrender. In an era when silence is complicity and culture is weaponized to erase memory and stifle dissent, what’s needed is a revolutionary pedagogy, a cultural politics that teaches us to remember, to resist, and to reimagine the world. As the late political philosopher Sheldon Wolin warned, “the central challenge of our time… is about nurturing a discordant democracy,” a task that depends on awakening “the civic consciousness of the nation.” This means placing culture at the very heart of politics – where critique, agency, and the radical imagination converge. •

This is an extended version of a shorter piece published in Truthout.org.