Building Up Germany’s Die Linke After the Election!

Die Linke (The Left) has staged an impressive comeback. But even more is possible. It can become the strongest political force to the left of centre. The party was successful due to anti-fascist class politics, a strong grassroots campaign, pointed public work, and extremely strong teamwork – but also due to mistakes by other parties and fortunate circumstances. The new voters want social justice, but also climate policy and protection of democracy. If Die Linke wants to continue winning, it must further develop its anti-fascist and ecological class politics and be prepared to address its own contradictions and weaknesses.

1. The shift to the right and the comeback of the Left

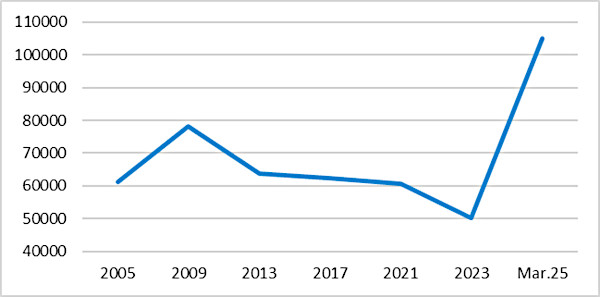

The federal election expressed a clear societal shift to the right.1 Against this background, Die Linke achieved a renaissance that surprised many. With almost 9 percent, it made an impressive re-entry into the Bundestag. Just weeks before, it was polling at 3 percent. It built a new voter coalition of younger people, those with higher qualifications, an above-average number of unionised employees, and the unemployed. After the election, it reached between 10 and 12 percent in initial polls. And: Within about five months, Die Linke gained almost 60,000 members; in late autumn it had about 49,000 members, and by early March over 110,000. According to a post-election survey by the polling institute INSA, about a third of voters today position themselves to the left of centre. Neck and neck with the SPD, Die Linke now finds support among about a quarter of these leftists, with the Greens still at 20 percent.2 But how exactly did the party manage this resurgence?

The rebirth of Die Linke is the result of hard work. Decisive steps toward renewal were prepared from January 2023; in summer 2023, the so-called Plan 25 was adopted, without which Die Linke would not be where it is today.3 In September,4 a large “Left Future Conference” took place in Berlin. It is tempting to think that there is a single reason for success in the federal election. It was neither simply the focus on social issues that had been discussed more intensively in the party since late summer 2024, nor the impressive door-to-door campaign alone. It’s more complicated. If Die Linke wants to repeat its success and become even stronger, it’s important to examine the various ingredients of the electoral victory carefully in order to strengthen what works and remove obstacles. In my view, it was due to a flexible interpretation of an almost left-populist strategy, an anti-fascist class politics that was supported by a strong grassroots campaign and made known through an excellent social media campaign. Added to this were favourable circumstances and mistakes by other parties that prepared the field for Die Linke – such as the abandonment of the social question by the other parties, the stark polarisation in asylum policy, the joint vote of the Union, BSW and FDP together with the AfD, but also the effectively hopeless race for the chancellorship for the SPD and Greens. However, Die Linke cannot rely on such favourable conditions in the future.

A thorough analysis leads us not only to the recipe for success but also reveals weaknesses that Die Linke must address if it wants to continue to be successful and permanently shift the balance of power to the left. It is advisable to take a closer look at the concerns and worries of those who identify with the new voter coalition. This way, clues can also be found as to how Die Linke can become even stronger. Today it is quite realistic that it could become the leading party to the left of centre – a Project 15% is feasible if it develops anti-fascist and ecological class politics. Die Linke should pursue this goal strategically, also to enable new political majorities and perhaps even alliance possibilities in the country.

I will try to make this thought plausible in what follows. I will first discuss the election results, the left-wing electorate, the explanation for the success, and the motives of left-wing voters. I will pay particular attention to the grassroots campaign (at its core: a door-to-door campaign that listened), which was a very special and important part of the election campaign. Finally, I will address some problems and challenges and draw strategic-practical conclusions (4) that would enable Die Linke to fight for leadership in the political space to the left of the Union.

Even though Die Linke has re-entered the Bundestag surprisingly securely, one must begin with the obvious: this was the great electoral success of the right, especially the post-fascist AfD. The centre-left suffered an immense political defeat. 20 years ago, when the then Red-Green government lost its majority in 2005, the SPD and Greens together had united about 20.03 million votes. In this federal election, there were only 13.91 million votes. Compared to 2021, the SPD lost around 3.75 million votes, a decline of almost 32%. 2.48 million voters went to the right, 1.76 million to the Union, the rest to the AfD. The Greens got off relatively lightly in comparison, losing around 1.1 million votes net, a decline of around 15%. The big winner of the hour is the AfD – in terms of content, because it has driven the other parties with its xenophobic policies, and consequently also at the ballot box. In 2021, about 4.81 million people gave their vote to the post-fascists; now it was 10.33 million.

This election took place not only because of the failed traffic light coalition politics; this collapse of the coalition also represents the failure of a moderate social and ecological reform of capitalism from above. There was no willingness to do this not only among the parts of the upper middle class and the bourgeoisie who are organised in the FDP. The orientation of the Union parties also indicates the reluctance that exists in other parts of the German upper class. If you add to this the great “rearmament consensus” that existed between the SPD, Union, Greens and FDP, and their lack of willingness to critically engage with the human rights violations of the Israeli army in Gaza, this explains why Die Linke was able to reposition itself as a political alternative.

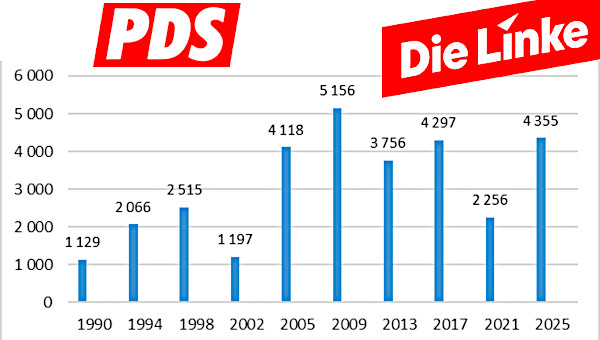

Against this background, Die Linke’s election campaign was a great success. Die Linke has, if you include the prehistory of the PDS [Party of Democratic Socialism], achieved the second-best result in its history. Based on the number of absolute votes cast for it, support was only greater in 2009, in the shadow of the greatest crisis of capitalism since 1929. Voter turnout differed in the various election years, but the absolute votes cast show the strength of the need for an explicitly socialist party.

2. Task: Becoming the leader to the left of the Union

According to relevant guides, the recipe for successful election campaigns goes like this: You need a party that appears united externally, thus radiating strength, stability and vision; internal solidarity is needed, which inspires members and shows voters sympathetic people; a clear objective of whom you want to mobilise for your party’s election; a catalogue of demands appropriate to this goal, a vision of a better society and a narrative of how and why you will actually achieve the concerns of your own supporters. Candidates don’t have to be super-charismatic (Kohl, Merkel, Jeremy Corbyn, Bernie Sanders – any more questions?), but credible. This also includes public relations work that penetrates because it has a recognisable common thread and can connect not only to convictions but also to basic feelings.5 For a left-wing party that doesn’t swim with the establishment, it is also necessary to be able to address people directly: as a guarantee of being able to get into conversation with them at all and as an opportunity to convince those who are doubtful.

Die Linke did all of this – crazy enough – correctly in 2025.6 But that is no coincidence, but the result of hard work. Since the beginning of 2023, under the conditions of a split from the party, the renewal of the party was prepared in the circles around the chairpersons Janine Wissler and Martin Schirdewan; in June 2023, “Our Plan 25: Comeback of a Strong Left” was adopted. This aimed to clarify the substantive profile, to unite the party, to clarify disputes in solidarity, to emphasise the political usefulness of Die Linke more strongly, and to open the party more to society and to actively recruit new members. Financial resources and also personnel resources were made available for this, and a so-called “renewal hub” was set up in the party headquarters. The party resolution from summer 2023 ends with the sentence: “We will confidently re-enter the Bundestag.” It’s wonderful when a plan works.7 That it could work was also due to the fact that volunteers brought it to life, helped develop it and made it reality. The so-called “Left Future Conference,” which was organised by members in Berlin in September 2023, was also important for this. Here,8 central ideas of party renewal were discussed – what belongs to the profile of a modern socialist party, what can we learn, for example, from the electoral successes of the KPÖ in Austria or the PTB in Belgium, how important are organising and door-to-door campaigning for the party, or also: how does ecological class politics work? Under the ashes of the old, something new was created.

The reason for the success in the federal elections is a flexible interpretation of the strategy9 to put social issues in the foreground, to address workers and employees directly, and to make class inequality10 an offensive topic. This was discussed in the party under “thematic focusing.” In the flexible interpretation of this strategy, however, something else emerged: a kind of anti-fascist class politics that we should develop further. Or to put it another way: The election campaign gives some indications of how we can make our party a stronger left party – with the goal of a modern socialist people’s party.11

Die Linke has succeeded in building a new voter coalition of rather young people, those with higher qualifications, especially employees and the unemployed, who live more in the west than in the east. Social concerns are very important to these voters, but concerns about climate/environment and the development of democracy also drive large parts of this coalition. This voter alliance is the result of a successful campaign and the strategic choice that the party has made. But it is also a consequence of an exceptional political situation, special political circumstances, which probably will not remain so. If Die Linke wants to repeat its electoral success, it must develop its strategy further – toward a socialist class politics that is anti-fascist and ecological.

Die Linke must advance the rebuilding in East and West Germany, anchor itself more strongly in the West and build on strengths and renew its foundation in the East. The guiding claim must be to break the dominance of the SPD and Greens in the centre-left political space and become the leader itself. The upcoming local and state elections are important stages for this – even in many western German cities, given the federal election results, it is not audacious to seriously enter the race for the mayorship. All this is possible due to the political situation and the political vacancies of both competing parties on the one hand, and due to the enormous increase in membership since October/November 2024 on the other. Die Linke now counts over 100,000 comrades – a doubling in a few months. “This is effectively a refounding of the party: around 60% (exactly: 59.9%) of Die Linke’s members have joined since the 2021 federal election, more than 50% since Wagenknecht’s departure.”12 Die Linke has the chance to break the dominance of the SPD and Greens among socially oriented and progressively thinking people – but this can only succeed if political stumbling blocks that stand in the way are also addressed.

3. The Social Composition of the Left voter base

Parties never have a homogeneous electorate; as a rule, they are voter coalitions from different classes, social strata or milieus. This always means: Voters from different strata do not have to have the same concerns and interests; they can even partly contradict each other. The task of a party is always to build such a coalition, i.e. to conduct politics in everyday life, in parliaments and in public in such a way that different concerns do not contradict each other but get a common perspective.13

The data available so far suggests that Die Linke has succeeded in building a middle-bottom coalition of younger highly qualified people, particularly many unionised “employees” and the unemployed. Socially (not numerically) speaking, Die Linke is thus almost a people’s party. But only almost. Middle-aged people vote for us only averagely, older people and workers (still) below average.

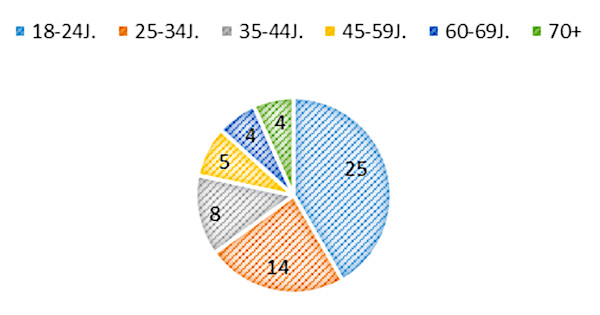

The left electorate tends to be young.14 25% of 18- to 24-year-olds and 16% of 25- to 34-year-olds voted for Die Linke, but only 8% of 35- to 44-year-olds and 5% of 45-59-year-olds.

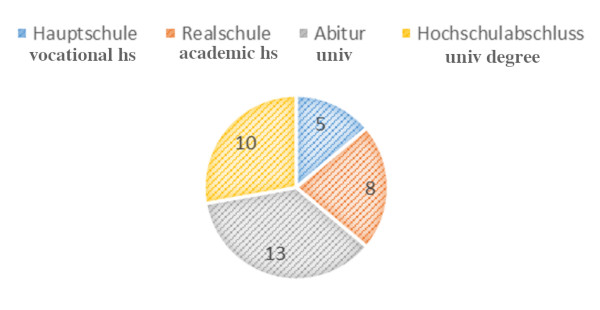

Furthermore, Die Linke voters are better qualified and relatively evenly distributed across the occupations that are surveyed in election polls. According to these, 5% of those with a Hauptschule [grades 5-9, vocational] diploma voted for Die Linke, 8 percent of Realschule [grades 5-10, academic] graduates, 13 percent of those with Abitur [university entrants], and 10 percent of Hochschulabschluss [university degree].

This fits with the societal development trend: Among the young cohorts of 15-28 year-olds today, around 43 percent have an Abitur and about 31 percent have a Realschule diploma. Conversely, however, this also means that Die Linke has performed too poorly among the group of young people who have a particularly difficult time socially (due to a Hauptschule education qualification, which is increasingly devalued). There is room for improvement here.

Among those who stated they were workers, 8% gave them their vote, 9% of employees, 7% of the self-employed, 5% of pensioners, and 13% of the unemployed. Among union members, Die Linke performed slightly above average, with 9.9% giving them their vote – below average among unionised workers (7.8%), strongly above average among unionised employees (which probably includes nurses, sales staff, etc. in their self-image), where it was 12.3%.

In the long term, the voter base has shifted from East to West Germany. In 2002, around 12% of all votes that the PDS was able to win were cast in West Germany (without West Berlin). Of the votes won in 2025, around 70% were won in the West (without West Berlin). In 2009 it was about 58%, in 2017 already around 66%. In 2025, there can be no talk of an East party, even though proportionally more votes were still won in the East than lived there proportionally (at the end of 2023, around 15% of all Germans lived in East Germany, without East Berlin). In Berlin, the PDS won 11% of all its votes in 2002; in 2025 it was about 9 percent. The renewal of the party must progress in the East as well as in the West. The successes in the West show: The chance of broadening and better social anchoring of the left party base in the West is there. Now it must be used.

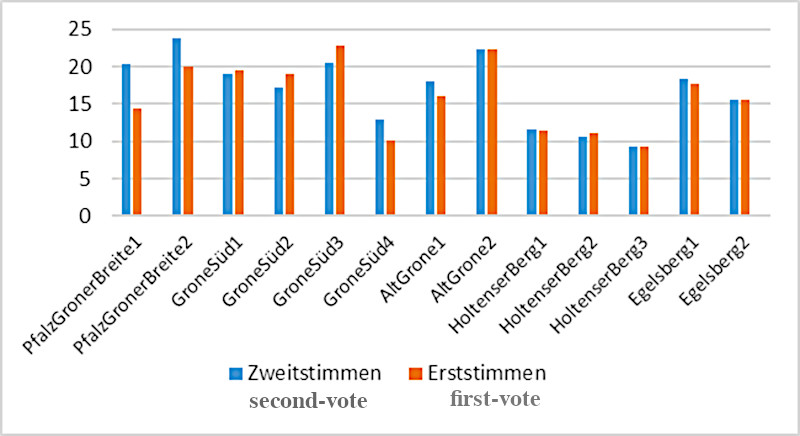

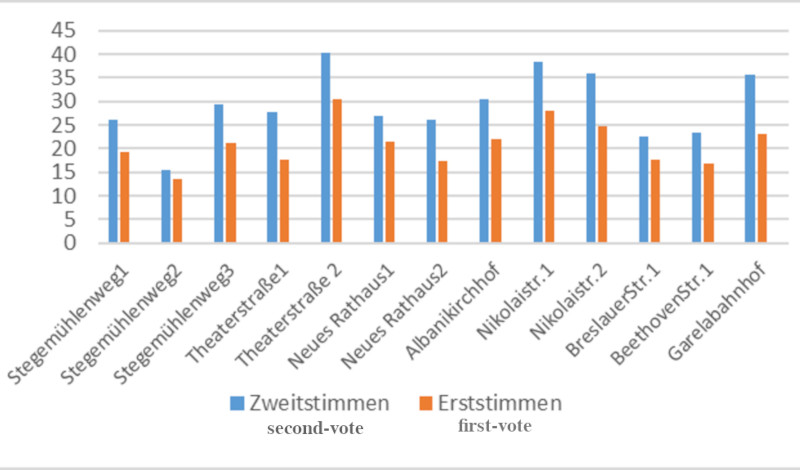

That Die Linke was able to build a middle-bottom voter coalition, I want to show finally based on some impressions from the city of Göttingen, which I know best. In Göttingen, we won a total of 17.6% of the second votes and 13.5% of the first votes. Very preliminarily: Through various campaign means, but not least through a long-planned and intensive door-to-door campaign (over 10,000 doors rung), we succeeded in gaining very good support from lower and lower-middle classes in addition to very high approval among the more academically qualified. This is shown here only by way of example based on individual electoral districts. To avoid misunderstandings: This is merely to illustrate a tendency, not a systematic evaluation.15

Grone Süd, for example, is a city district with a strong migrant character, where there has been a left-wing shop since last autumn. Holtenser Berg is considered a relatively poor district where the AfD is particularly strong (32-34%). In comparison to the city, we performed below average in these three electoral districts, but still significantly above average compared to the federal level. We conducted door-to-door conversations in all the districts shown, but only once in Holtenser Berg. In comparison, here are the even higher values from electoral districts with higher proportions of academically educated people. We also conducted door-to-door conversations in these electoral districts, addressing younger people in particular, but also through our participation in protests against the right.

4. Momentum for Die Linke: What explains the success?

Failures are always the responsibility of others, successes always one’s own. This is a rule of thumb in politics. Responsible functionaries of Die Linke would be well advised to forget it. In fact, a number of conditions come together to explain why Die Linke performed relatively strongly. Some have to do with day-to-day politics and the strategic (mis)decisions of other parties, but many also with the right decisions and course settings in the party itself. And perhaps one should note at this point: It was a race against lost time. The BSW pursued the destruction of Die Linke from within Die Linke until the last possible moment – only in January 2024 did Wagenknecht and Co. found their own party, the image damage for Die Linke was almost total. Politics is time. And until the European elections in June, valuable months were missing to be perceived differently in public than as a ship that had run aground, as divided and at odds on several central political issues. That could have gone wrong – just as the BSW strategists had calculated with a view to the European and state elections.

The less time remained, the harder it was for Die Linke to credibly stand for left positions. Nevertheless, the right course was set during this time. This included the orientation toward a long-term renewal and pre-election campaign, which was already initiated in late summer 2023, the targeted opening toward the societal left, and in many places the “renewal from below.” And it included the strategic debate about a new left narrative, more targeted campaigning, an almost left-populist framing, and the need to elect a new party leadership – not because the old one had done many things wrong (it did many things right), but because a fresh start sometimes needs new faces. The fact that Janine Wissler and Martin Schirdewan initiated this transition is also one of the conditions for the current success.16 As a result, Die Linke entered the race in December 2024 underestimated.

The federal election was characterised by the failed government (price increases/real wage losses, continued significance of high rents, failed climate transformation, rearmament in the context of the Ukraine war and the new hot-cold war), the expected chancellorship of Friedrich Merz (no momentum that would have brought voters to the SPD and Greens) and the growing approval for the AfD (connected with events that brought the danger from the right into consciousness: remigration plans at the beginning of 2024, joint voting of the Union, FDP and BSW with the AfD). Among the special conditions is certainly how unpopular the chancellor candidates were: “No one’s hearts flew to the voters. On the contrary, both the old and the new candidates had to contend with strong reservations against their person.”17

A favourable situation was thus created for Die Linke, which could be used through a flexible interpretation of the election campaign. The campaign itself envisaged essentially addressing the social question and the top-bottom divide, and in this way also addressing the catastrophe of global warming on the margins (“Is your village under water, the rich climb onto the yacht”) (similarly with the question of war and peace) – but taking a stand on other issues. In this way, the party was able to talk about the mother of all problems in the country, about the unequal distribution of wealth, and about all the resulting imbalances and concrete problems for the people. Important in this context: According to the ARD-Deutschlandtrend, 77% of respondents at the beginning of January saw the greatest problem for living together in Germany in the huge differences between rich and poor – neither the Greens and the SPD nor the BSW took up this deep sentiment by intensifying their campaign. These were strategic mistakes through which the political field was largely left to Die Linke in this respect. The treatment of the social top-bottom divide was well complemented by the narrative, which was practically underpinned by the door-to-door campaign and the heating cost campaign, that Die Linke wanted to do politics differently: listening, starting from the people and their everyday concerns: “With the programme that wants to seriously take on capital and the super-rich in order to master the crises of our time within the framework of a social-ecological transformation, there remains a unique selling point in the political business.”18

But this alone did not do justice to the political moment. Only through the anti-fascist and anti-racist momentum that was created by the Trump election in the USA, the break-up of the traffic light coalition, the dominance of anti-migration positions, and the voting intentions of the CDU together with the AfD, did Die Linke additionally become an attractive project. This should not be thought of as a simple and direct connection (one event → political consequence), but rather as the formation of a mood that influenced people’s thinking. Events nevertheless play a role because something can emerge at them and in them that had already arisen before. Passions are then ignited at such events.

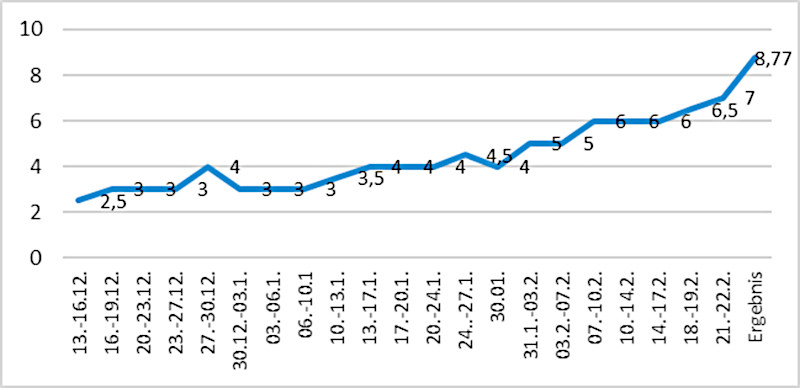

The announcement and vote on the CDU’s 5-point plan was such an event. The CDU’s approach stands for both the intensification in the migration debate and for an anti-fascist shock. In the surveys of the polling institute Insa, Die Linke slowly climbed from 3 to 4% between 03.01.2025 and 30.01. This good development was also a consequence of the social campaign management. But not alone. There was only a boost with the migration policy intensification and the anti-fascist polarisation – with Die Linke as the clearest pole of humanity, internationalism and anti-fascism. On 24.01. Merz had announced that he would put the CDU drafts to a vote, on 30.01. they were dealt with in parliament. In the survey conducted between 31.1 and 03.02, Die Linke climbed to 5% for the first time, then quickly to 6 and 6.5%.19

That Die Linke became attractive in this context was only possible because the party did not duck away but took a clear position – through framing and narratives that were not entirely successful (because improvised) but nevertheless effective. Jan van Aken showed a clear edge in the talk shows, Heidi Reichinnek gave a great speech. Both were picked up in social media and the press and shaped our external impact. Die Linke was – and this was already the case in the weeks before, as the intensifications in the migration debate increased – in the public eye not only THE social party, attacking billionaires and millionaires, but also THE asylum and pro-migration party. This also had a movement side because it was a credible voice in local protests in many places shortly after the Merz-AfD vote. That a clear anti-racist and human rights policy position was important for the electoral success is at least suggested by the high approval rates among German Muslims. 29 percent voted for Die Linke, presumably due to the position in the polarised migration debate and the clear criticism of the Israeli government’s violations of human and international law in Gaza.20

Both must be viewed in context, distribution and social policy and anti-fascism/anti-racism. One could also say: The connection of an anti-fascist class politics explains the success – of a left that stood by its internationalism without complexes. In this context, however, it is important to emphasise how this happened. The focus was on defending minimum standards. In this storm, the party had to manage without its own elaborated immigration concept and without a considered political narrative.

The climate issue, on the other hand, played a somewhat lesser role for the electoral success – but it did play a role. This is already shown by looking at who the new members of Die Linke actually are and what is important to them. At least for a good part of the new members, one can say in a pointed way: Parts of the left wing of the climate movement and its supporters have increasingly appropriated the party over the past two years – explosively since November 2024. This should also stand for political orientations in the corresponding strata and milieus from which the new members come, at least to a larger extent. Disappointment with the Greens in government made it possible to penetrate this spectrum. These people will only remain attached to Die Linke in the long term if it also pursues a left-ecological policy. In summary, it can be said: From the beginning of January, the party increasingly represented a progressive left populism in hand-to-hand combat, which was very red, but which also had an internationalist effect externally – and green on the politicised parts of the younger generation, who inform themselves well, were themselves active in the climate movement or supported it.

5. Concerns and Interests of Die Linke voters

This is also expressed in the concerns and interests of those who voted for Die Linke. Asked what had been decisive for them in voting, 51% of Die Linke voters cited social security, 18% climate + environment, 9% internal security, and 8% securing peace. Asked about their own greatest concerns, the picture was different:

84% were concerned that democracy and the rule of law were in danger; 82% that climate change is destroying our basis of life; 72% were concerned that Russia’s influence on Europe continues to grow; 72% were concerned that “we” are defencelessly exposed to Putin and Trump; 60% were concerned about money problems in everyday life; 60% about strong price increases, so that bills can no longer be paid.

In my opinion, these values express the importance of climate policy and the defence of democracy for the left electorate – and for the possible future supporters of Die Linke: For 91% of Green voters, climate policy is very important, but also for 76% of SPD voters. 64% of our voters thought too little was being done for climate protection; this was true for 55% of SPD voters, 80% of Green voters, and even 24% of BSW voters.

The concerns about Trump and Putin should also be interpreted primarily as an expression of a democratic basic attitude, as both are prominent faces of the new international right-wing authoritarians in the public eye. While the anti-fascist-democratic basic attitude that emerges in this is a point of connection for Die Linke, the worries and feelings of threat are a challenge. Because there is simply no elaborate left-wing security and defence concept that could be considered part of a convincing détente policy for our time to address these concerns. It is only clear that the policy of a freedom party, which Die Linke is, “(…) cannot consist in submitting to an apologetic alleged ’realism’ that allows the geopolitical great powers to divide spheres of influence among themselves in disregard of international law and popular sovereignty.”21 A convincing left-wing security policy does not yet emerge from this. This Achilles’ heel was also recognised by the Greens and SPD: A good part, especially of the younger people, voted for Die Linke (this already applies to many of its new members) despite the peace and foreign policy positions attributed to it, not because of them.

6. The Importance of the grassroots campaign

The left populism of the left election campaign was rebellious and it was – and this is important – engaging because the faces of the party appeared warm, energetic, credible, and smart. But this was only possible because important organisational policy decisions had been made. This includes the improvement of social media work – much has already been written and said about TikTok,22 but it applies to the public relations strategy as a whole, in which a basic narrative (We against the upper classes, for the working people, etc.) was maintained.

But at least as important is that, as part of a door-to-door campaign, a real grassroots mobilisation took place in many locations. In my opinion, three things were decisive here. Firstly, since September, first small, then growing swarms of campaigners have actually gone to the doors in many places. They were also able to reach those who wanted to turn away in frustration, who wavered or – this happened again and again at least in Göttingen – actually wanted to vote for the BSW or the AfD. The impact of this campaign on the overall election results (it is clearly present in the winning of direct mandates) still needs to be systematically reviewed. There were several large district associations where there was no door-to-door campaign and yet very strong election results were achieved. A Lower Saxony example is the city of Oldenburg. For Göttingen, however, it can be said: Where a door-to-door campaign was conducted, it was possible to achieve strong vote increases even in the districts where people with little money live. Secondly, due to the grassroots campaign, a dynamic emerged locally in which other forms of active campaigning could be done better (leafleting, information stands, campaign festivals…). The door-to-door conversations were, for example in Göttingen, the central axis of the campaign, in which – to a very different extent – around 120 people participated. This created an overall atmosphere of optimism. In this context, we were able to distribute our information materials throughout the entire city and also in parts of the large rural area of our constituency – according to feedback from several citizens in conversation (admittedly, a very subjective basis for evaluating this), an impetus to deal with our positions and the party. This applies explicitly to waverers who wondered whether to vote for the SPD, Greens, or Die Linke. And thirdly, due to the active grassroots campaign, new members could be directly offered an opportunity to participate. Not to be underestimated is the new image that Die Linke projected outwards through thousands of active grassroots members: an active party that is really interested in people and their concerns.

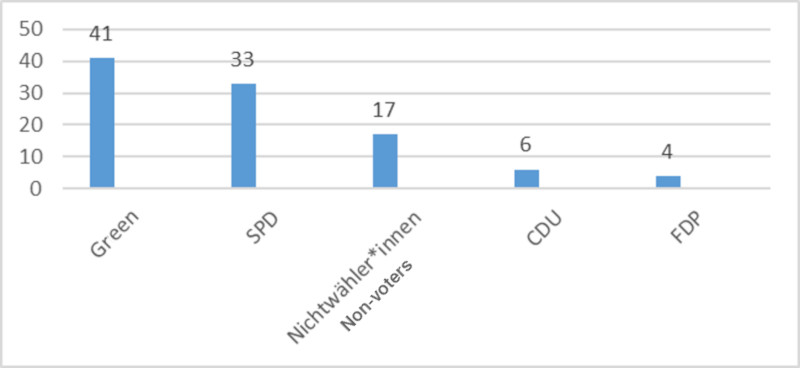

In this way, it was possible to win voters both from the two centre-left parties and from the non-voter spectrum. Die Linke gained most strongly from the Greens and the SPD. Of all the 1.45 million votes lost by the Greens, almost half went to Die Linke. This also shows: Die Linke was successful as a left-green party. At the same time, it lost to the right: 110,000 votes to the AfD and 350,000 to the authoritarian-social BSW. Certainly, some of those who left wanted a less Russia-critical foreign policy – another part was probably attracted by the right-wing course of the BSW in social and environmental policy. Overall, after this small “exchange,” Die Linke’s electorate in 2025 should think more progressively on these issues than in the past.

There was never a strategy in Die Linke in recent years to primarily win disappointed Green voters. However, this was repeatedly claimed by critics of the party executive last year – combined with the indication that this strategy had failed, that Green voters were not or hardly to be won. In the federal election, however, this is precisely what Die Linke has particularly succeeded in doing. The vote gains are considerable. But only in combination with the gains from the SPD and from the non-voter spectrum did they secure success.

In 2025, it was also true that: Voter turnout was lowest where people with low incomes and formally low educational qualifications live.23 Of the gains that Die Linke was able to achieve compared to 2021 (only the votes gained are considered), the gains from the Greens accounted for around 41%, those from the SPD 33%, from the non-voter spectrum 17%.24 This is crucial for the future strategy debate. It must be about breaking the remaining dominance of the SPD and Greens in the centre-left camp by addressing their “left-affine electorate” on the one hand, reaching non-voters at the same time, and taking up the social concerns of the non-firmly-right parts of the AfD voters. As a reminder: Among non-voters, there are above-average numbers of people with low incomes, older people, and workers who feel left behind by the prevailing politics.

7. Strategic Conclusions – Project 15%

The new situation – presumably a renewal of the Grand Coalition (albeit with a junior partner SPD) – offers much space for a clear left opposition. However, the Greens will also reorient themselves in opposition by opening up socially to the left – as they have done in the past. And given the exploratory results, further rearmament in an open amount is to be expected (the debt brake is to be opened only for the defence sector), despite around 50 billion per year investments in infrastructure (500 billion special assets over 10 years), at best social standstill, rather deteriorations and further dissatisfaction in what remains of social democratic voter milieus. At the same time, fundamental partial causes of the AfD’s successes will remain.

Against this background, it is important for Die Linke to address its own weaknesses and contradictions, and to draw strategic conclusions that actually enable it to become the leading force in the centre-left spectrum. One is not necessarily leading because one wins the most votes – one can also be leading because one has earned the strongest real political support from active civil society and makes the proposals in the social conflicts to which others must react. We are hegemonic when others carry our ideas on their lips, even if it is to deny them.

Toward the SPD and the Greens, a dual strategy is therefore necessary: Through hard confrontation and criticism, Die Linke must make clear its own political usefulness (why support Die Linke, not SPD and Greens?) and address those who have already been politically left behind by both parties today. In this respect, a strategic dividing line is necessary that is drawn clearly and distinctly. But that alone would be insufficient because it does not open up an implementation perspective for one’s own proposals. And because the commonalities that exist between Die Linke, SPD and Greens at least on paper are ignored – and where Social Democrats, Greens and Die Linke work together in alliances, trade unions and works/staff councils, movements or initiatives. The dividing line must therefore be complemented by offers of cooperation that are honestly meant in order to implement concrete improvements.

In the following, I will now draw some strategic conclusions to outline the project of a pointed left-populist, anti-fascist and ecological class politics that could help make Die Linke a strong pole in the party dispute. This is the prerequisite for also stopping the increasing influence of the AfD among workers and ordinary employees and regaining political ground. Because one thing is also clear: If Die Linke wants to change the majority conditions in the country, it must break the influence of the AfD in the lower income strata. This requires a sober examination of the AfD’s supporters, distinguishing between racists and xenophobes on the one hand and people on the other who adopt a scapegoat ideology to process social and political experiences of suffering, but who are not firmly right-wing. How large these two parts are is disputed. As a “class left without complexes,” Die Linke must try to reach the latter. This is precisely where the following applies: There is no point in concealing one’s own internationalism and ecological convictions. Rather, it’s about honestly addressing the social interests of AfD voters and convincing them – truthfully – that the enemy doesn’t come to us in dinghies, but flies in private jets. To be able to do this, it’s advisable to evaluate experiences with organising and supportive political work, e.g. in neighbourhoods (see below) and to continue with it, and at the same time to address a widespread political unease about corporate and lobby power.

Die Linke as the engine of democratisation: A fundamental political feature of our time is the double unease about democracy. By this I mean, on the one hand, the fear of fascistisation and a shift to the right, and on the other hand, the criticism of lobby and corporate power, which is widespread among the population, especially among non-voters. A more widespread feeling is that one has been forgotten by the political establishment. Die Linke addressed both in the election campaign, on the one hand with the claim to “want to do politics differently,” on the other hand through the clear anti-fascist stance. This double political unease about democracy can be addressed through a democracy-centred left populism: We are concerned with the equality and equal dignity of all citizens and the building of a real social democracy in which claims to equality are also realised. This left republicanism also includes – as economic republicanism – advocating for extending common democratic decision-making to economic matters. Such left populism is challenging because the fear of fascistisation can strengthen people’s inclination to “defend democracy itself” and call for the solidarity of all democrats. The left democracy narrative must, in my opinion, be anti-fascist and in this sense republican, and at the same time attack detached politics in the interest of the billionaire and millionaire class25 – in the name of the social equality and freedom of dependent employees. The party needs an elaborated narrative. This must be arranged around everyday examples and open up a democratic vision: What would a more democratic country look like? And above all, a serious debate about the anti-fascist strategy is necessary. Left economic and social policy is important, no question. But left anti-fascism cannot be reduced to that.

Politics for working families: It is very good that Die Linke has become the party of young voters. A socialist party that cannot win young people has a problem. These successes should be built upon to expand them. But it is also a challenge in that young people are already a minority compared to older people in Germany. The 18 to 24-year-olds counted only 6.15 million people at the end of 2023, including non-citizens. That was only about 7% of all people living in Germany. For comparison: Just those who were 82 years or older made up a whole 6 percent of the population at the end of 2023. The 60-65 year-olds a whole 9%. As a reminder: Among the 35-44 year-olds, Die Linke reached “only” 8%, among the 45-59 year-olds 5% and among the 60+ 4%. Among the 25-34 year-olds, 14% voted for Die Linke. This is a very good starting situation, especially to fight for political ground in the spectrum of 25-45 year-olds. To achieve this, Die Linke should more strongly address the “working families” and take up their worries and needs more specifically. It is absolutely right, Die Linke has always stood for a social family policy, the bulk of its proposals (e.g. in education and social policy) enable families to have a better life. This includes, for example, the widespread expansion of care, education and support services.26 But families hardly appear in its public relations work and in its political narratives. The left leaves this emotional landscape to conservatives, social democrats and the right. The reason is clear. On the one hand, families are also places of coercion and lack of freedom, on the other hand, leftists do not want to exclude other life plans. But families are also places of love, of (shared) care and reproductive work, in good families of community spirit. This world of care(s) is predominantly the world of 25-50 year-olds – and these are the people the left should address politically. “Politics for working families” would at the same time allow it to build a bridge more specifically again to problems such as old-age poverty, pension policy and care: social problems that are particularly important for those who have voted least left, for the over-60s.

Class mobilisation and non-voter strategy: The lower the income and formal educational qualifications, the lower the voter turnout. Non-voters are of course not a uniform group, there are very different reasons why people don’t vote. One reason is that people who actually have left-wing demands and claims have been disappointed again and again and no longer felt/feel represented. This demobilisation is a guarantee of success for the other parties – all the more so as the AfD succeeds in motivating right-wing non-voters to vote. Die Linke has now also gained considerable approval from non-voters. This non-voter strategy must be expanded to target frustrated or politically wavering parts, especially of the lower working and middle class. The broad grassroots and door-to-door campaign has shown how this works: Going to the people in conversation, because frustration and political indecision can be addressed best by direct conversation. But more is needed. The approach of an “organising left politics” that lies behind the door-to-door conversations must be further conveyed and disseminated. Because on the one hand, Die Linke wanted not only to inspire its conversation partners to vote for it, but also to invite them to join in. On the other hand, the conversation with the citizens was only the visible part of an iceberg. The invisible part was and always is the activating, organising and empowering organising work in the background, through which more people are invited and supported to get involved in active party work. In this sense, Die Linke must continue to convey the organising knowledge,27 it needs thousands of left organisers in the party to fight even more effectively for those who have turned away.

But it is important in this context that the party as a home must offer everyone a place and also opportunities for participation. This means that the grassroots campaigns and grassroots work must also invite people who may only have two hours a month to spare for the party. Die Linke needs organisers, it needs activists and it needs a multi-layered participation offer for those who have less time.

Internationalist class politics: The federal election campaign has shown that Die Linke cannot choose the questions to which it must answer in public. It also doesn’t help to hide or tone down one’s own answers. Political opponents will throw the left’s positions in its face again and again. On TV, in social media, and in street campaigning. This applies to all topics, but especially to the topic of asylum and immigration. For Die Linke, which wants to be the party of the working classes, this is an important topic because a large part of the working class today can look back on its own immigration history. There are areas of the German economy – the meat industry is the best-known example, but it also applies to parts of warehouse logistics, care or system catering – in which today nothing works at all without migrant workers and refugees. The demonisation of immigrants is a fixed and central part of conservative and (post-)fascist strategies to be capable of winning majorities. Anti-migration politics will remain. It cannot be hidden because socialist class politics must try to overcome the division of the working class. The only viable way is to deal with it confidently and prepared. This means: To gain more political ground, Die Linke must systematically combine its social class narrative with a “pro-migrant” narrative. It would be about a multicultural class narrative that addresses and makes visible people who come to Germany as part of the working classes, does not deny the challenges that also arise through immigration but addresses them and presents its own solution proposals – and that emphasises its own internationalism and does not shamefully conceal it. But this also means: How immigration and immigrant people are talked about is not irrelevant – it’s about a targeted multicultural and pro-migrant class framing, which Die Linke does not have. Politically, this would be underpinned by its own proposals for a left immigration concept. This is also crucial because immigration into the labour markets will be an important topic in the future – simply and simply because companies demand suitably qualified workers. The Federal Employment Agency assumes that by 2025 alone, 400,000 additional workers from abroad will be needed annually.

Ecological class politics: The climate crisis is a social crisis, the climate question has always been a class question. Its development will shape our lives, and we must do everything to prevent the worst. What is needed is a fundamental change of direction, even a deep break in the modes of production and ways of life, for which we must win majorities. But also in terms of electoral strategy, “the climate question” is decisive because it is very important for large parts of the centre-left voter spectrum. The Greens in opposition will again try to position themselves as a credible climate party – voters that Die Linke has won from them (after all, 41 percent of the pure gains) can also switch back. If the party wants to keep them and reach the parts of the SPD voters (over 50 percent) who believe that today’s climate policy is not enough, it must continue to profile itself as a social climate party. This includes, in addition to good concepts, also a more offensive climate-populist narrative, as it already appeared in the election campaign, but must be expanded: In this class-climate politics, it’s about the responsibility of the rich for financing the ecological transformation, about truly effective measures, about the democratic participation of workers in decisions, and about protection and security for all ordinary people.

Answers to the government dilemma: Die Linke has benefited from a special situation this time. It was clear that neither the SPD nor the Greens had a chance to appoint the Chancellor. The change to a CDU-led government was certain. In this situation, unlike in 2021, no social change in mood toward another government arose. This made it “simple” for Die Linke to position itself as opposition. Even those who wish for a progressive government found it relatively easy to vote for us as an opposition party. This comfortable situation could, however, be over by the next federal election. Therefore, an answer must be found to the future question of why people should vote left if the party is not available for a change of government. In short: Die Linke needs a thought-out radical reformist narrative that can appeal to those who want a better government, and those who wish for opposition. If Die Linke wants to grow, it must address all those who would otherwise vote for those who will govern (this was in itself a well-considered attack by the Greens in the last week of the campaign, which only didn’t work because the Greens had massively disappointed voters, signalled too much willingness to form a coalition with the Union, and Habeck was far from having a chance at the chancellorship). Die Linke did not and does not have such a narrative. In 2021, for example, the slogan that it would advocate for “majorities beyond the CDU” was not advertising for Die Linke. Many voters translated “CDU out of government” for themselves as simply voting directly for the Greens or SPD.

Left security and a new détente policy: A major Achilles’ heel of the left’s electoral success is foreign policy. Concerns about authoritarian and aggressive states are spreading in a larger part of society – even among those whose hearts beat for a socially just and more democratic republic. What is decisive, therefore, is not only what insights and correct understandings the left has into world politics, but how it convincingly responds to these concerns. The values from Infratest-Dimap shown above illustrate the problem for the new electorate. But the situation is no different among supporters of the Greens and SPD. The party will have to deal with this quickly, because SPD and Greens are targeting exactly this with their attacks. However, it is also true that fears of military escalation are spreading – and if you listen to politicians from the Union to the Greens, then not without reason.

From the last election campaigns (state election 2022 and European election 2024, as well as the federal election campaign), I have nevertheless gained the strong impression that a significant part of the electorate votes for Die Linke despite the previous answers, not because of these answers. This does not have to be the case in the new multipolar world, in which even NATO is effectively called into question by Trump’s USA, and several authoritarian states and state blocs come into conflict with each other.28 The security policy answers of the other parties are narrowly focused on military reactions and the future military development of spheres of influence and raw materials. This is an offensive insecurity policy. Left security policy must first of all demand a sense of reality and insist on reducing insecurities and avoiding violent conflicts, first and foremost focusing on civilian solutions – based on its own cooperative defence policy, which is designed for structurally defensive defence. The decisive factor is to seriously elaborate such a defence policy and to adopt an attitude that leaves no doubt that Die Linke stands for freedom and democracy in a world where imperial powers trample on international law.

For the daily debates, self-confidence is initially called for: The value of the Left is “that there is at least one voice in the Bundestag that doesn’t simply march along, but questions the renaissance of the military. Without being either naive or wilful – like the Kremlin parties AfD and BSW29 – ignoring the real threat to the European order from Putin’s Russia.” This is precisely why the party must work on a convincing concept of détente policy – only then can it also gain more support for the no to rearmament and militarisation. It would be advisable to start both from the questions and concerns of the people in the country and from the upheavals in the world. Die Linke could even be a pioneer here. Because the USA under Trump seems to want to leave little of the so-called “Western community of values,” old alliance systems can already seem outdated in the shortest time, the loyalty in the headquarters of the SPD, FDP and Union toward Washington can become an absurd pose. The task of the Left would be to formulate an anti-imperialist policy at the height of the times – which must also include how security and democratic self-determination can be preserved against great powers that – whether Ukraine or Greenland – claim to be able to shift borders. The social democratic concept of détente policy, to which many in the Left like to refer, always stood on two pillars. It would be further developed from a left-socialist perspective. One pillar was to rely on diplomacy and “change through rapprochement,” i.e. to reduce tensions and enable democratic progress in the partner countries of détente policy through more exchange with them. The second pillar was the idea of a structurally defensive defence. Both were a unity – and the question would be how exactly good defence would look today, without participating in the arms race that will increase tensions and insecurities even more.

8. In Conclusion: The Strategic Choice

Die Linke has made an impressive comeback that has surprised many commentators and observers. Many overlooked the correct course settings that had been made in the party since the beginning of 2023. In the summer of 2023, these culminated in the so-called “Plan 25.” With this, Die Linke began to work strategically on its renewal. That’s why in autumn 2024 it did not enter the race as a ship that had been shipwrecked. In many places, volunteers had driven forward the renewal. Party headquarters and the Bundestag group had initiated important steps – major tasks and challenges remained and remain. But Die Linke started as a racing boat that had just been refitted. This shows: If the party sticks together, if it appears united externally and strategically pursues a plan, it can win. Even now it has the strategic choice: It has the chance to become the strongest party to the left of centre if it does the right thing.

It has won 41 percent of its new voters from the Greens, 33 percent from the SPD and 17 percent from the non-voter spectrum. Although the available data from the election surveys must be interpreted with caution: These people seem to desire social justice and equality, social climate protection, anti-fascist-democratic politics and a foreign policy oriented toward the protection of democracy. This is also suggested by data on the attitudes of SPD and Green voters after the 2021 federal election,30 who together made up almost 75 percent of the newly won Die Linke voters in the 2025 election. If Die Linke wants to continue winning, it must further develop its anti-fascist and ecological class politics. This also includes continuing to struggle for non-voters and trying to address the socially angry fringe of the AfD electorate. It must be about strengthening the societal anchoring of the party and broadening the previous voter coalition by connecting different concerns and interests. To achieve this, Die Linke must be prepared to address its own contradictions and weaknesses, and to build on strengths.

I have finally presented some construction sites on which the party would have to work together in solidarity: developing a clever strategy toward the Greens and SPD, addressing more the unease about democracy and its crisis, expanding active grassroots work, addressing working families, strengthening anti-fascist, internationalist and ecological class politics, developing a convincing government and power narrative, and working on a left security and détente policy that addresses the fear and concerns about autocrats on the one hand, military escalation on the other.

A self-confident and willing-to-learn “Left without complexes” can succeed in this. Then it is possible to shift the balance of power in the country back to the left and defeat the current right-wing bloc of Union and AfD (around 49 percent of the votes) – the future is open. And perhaps it is red. •

This article first published on the emanzipation website and translated for Europe Solidaire by Adam Novak.

Endnotes

- I wrote this text from the perspective of a volunteer activist of Die Linke. I worked in the scientific advisory circle of the former party chairman Bernd Riexinger, accompanied strategic debates in the circle of the former chairwoman Janine Wissler, and have been district spokesperson of the left district association Göttingen Osterode since 2020. I am also a member of the state executive of the party in Lower Saxony. In 2021 I was a direct candidate for the Bundestag election, in 2022 for the state election, in 2024/25 again for the Bundestag election. In Göttingen we conducted election campaigns in 2021, 2022 and 2024/25 in which door-to-door conversations played an important role. As a direct candidate, I have been able to have many citizen conversations in recent years. When I describe my impressions of moods and attitudes among voters and sympathisers in the following and do not substantiate these with surveys, I am referring to these conversations. So it’s everyday political empiricism.

- INSA-News, Issue 497. Email newsletter of the polling institute INSA.

- See the resolution of the party executive from June 2023: Our Plan 25: Comeback of a Strong Left.

- See: Zukunftskonferenz.

- Frank Stauss (2013): Höllenritt Wahlkampf. Ein Insider-Bericht. München.

- Mario Candeias (2025): Die Linke – Ein Wintermärchen. Zeitschrift Luxemburg.

- Our Plan 25. Comeback for a strong Left.

- See: Zukunftskonferenz, and on the event itself.

- Ines Schwerdtner und Jan van Aken (2025): Das Comeback der Linken.

- Thomas Goes: Stolpern, hinfallen, aufstehen (2024): 21 Thesen zur Krise und Erneuerung der Linken.

- Thomas Goes (2024): Eine moderne linke Volkspartei.

- Moritz Warnke, Bundestagswahl 2025, S. 8. See above.

- Bruno Amable und Stefano Palombarini (2018): Von Mitterand zu Macron. Über den Kollaps des französischen Parteiensystems. Frankfurt/Main.

- See this and other data on the social composition of the electorate.

- See this data.

- Mario Candeias (2025): Die Linke – Ein Wintermärchen. (See above.)

- Catrina Schläger, Jan Niklas Engels, Nicole Loew (2025): Analyse der Bundestagswahl, 2025. p. 12.

- Moritz Warnke (2025): Die Bundestagswahl 2025, p. 5.

- See the long series on Insa.

- Özgür Özvatan: Von der AfD umworben, zur Linken neigend: So stimmten Wähler mit Migrationshintergrund.

- Alban Werner: Unverhoffte dritte Chance.

- Marco Saal: Die Linke und der spektakuläre Siegeszug auf Instagram und TikTok.

- Catrina Schläger, Jan Niklas Engels, Nicole Loew: Analyse der Bundestagswahl 2025, p. 15.

- Tagesschau 23. Feb. 2023.

- Thomas Goes: Welche Strategien gegen den Rechtsrutsch?

- See also the debate on so-called infrastructure socialism: Mario Candeias/Barbara Fried/Hannah Schurian/Moritz Warnke (2020): Reichtum des Öffentlichen.

- Robert Maruschke: Linkes Organizing.

- Kavita Krishnan (2022): Multipolarität – Das Mantra des Autoritarismus. emanzipation 6.1, p. 161–172

- Pascal Beucker: Der Pazifismus der Linkspartei.

- See e.g. Steffen Mau/Thomas Lux/Linus Westheuser (2024): Triggerpunkte. Konsens und Konflikt in der Gegenwartsgesellschaft. p. 351f.