The Sri Lankan Left’s Long Road to Power

The victory of the National People’s Power (NPP) candidate, Anura Kumara Dissanayake, in the Sri Lankan presidential election represented a major shift in the South Asian state’s political trajectory. Dissanayake’s upset was soon followed by parliamentary elections in which his coalition won two thirds of the seats, an unprecedented feat since the system of proportional representation was established in the late 1980s. For the first time since the 1970s, a left-wing party is not only participating in a government coalition, but leading it. This uncharted political territory represents a great opportunity to put Sri Lanka on a more sustainable, egalitarian developmental path, but also poses great risks. The NPP could buckle under institutional inertia and international pressure, and fail to deliver the kind of change for which it was elected. Consequently, the stakes are high for the broader Left movement in this historic moment.

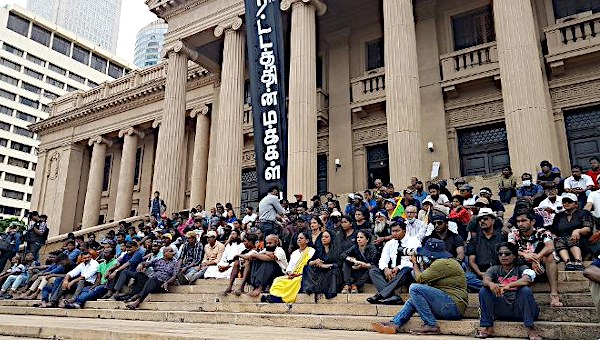

The recent political earthquake comes after two years under President Ranil Wickremesinghe, whom the establishment, ranging from mainstream media and think tanks to foreign lenders, credited with bringing “stability” to the island nation. Following years of gross mismanagement and incompetence on the part of previous President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Sri Lanka defaulted on its foreign loans for the first time in April 2022. The ensuing economic crisis led to long queues for fuel and basic items, and soon provoked tremendous popular protests culminating in the aragalaya revolt that ousted Rajapaksa in July 2022. Yet, after the uprising died down, a subsequent government led by Wickremesinghe suppressed dissent and carried on with an International Monetary Fund-led programme of brutal austerity measures. Meanwhile, the people bided their time until the next election.

Decisive Victory

It was in this tense atmosphere that the left-leaning NPP was able to win such a decisive majority, assuming office amidst great hopes and expectations. The NPP is primarily the vehicle of its chief constituent party, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP). As the leader of both the JVP and the NPP, Dissanayake has portrayed the latter as a third force. He counterposes it to the corruption of the political class and its favoured home in Sri Lanka’s two historic parties, the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) and the United National Party (UNP), along with their contemporary offshoots, the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) and the Samagi Jana Balavegaya (SJB).

That said, we should not forget that the JVP’s move to form the NPP in 2019 was in part intended to deflect attention from its own bloody history, including its first armed insurrection in 1971 and an even more brutal attempt in the late 1980s. At the same time, the NPP’s victory aligns with global trends, as ever-larger groups of voters swing between left- and right- populist alternatives to the political establishment from one election to the next.

The NPP shares many of the ambivalent characteristics of left-wing formations in other countries in which neoliberalism has become politically dominant. Yet unlike the main left-wing parties in India, for example, which have governed in states such as Kerala and West Bengal for decades, the NPP is assuming power at a time when the political and economic order is already fraying. Nevertheless, despite the severity of the economic hardship and the ferocity of the 2022 revolt, it remains uncertain whether Sri Lanka’s new government will be willing to take steps toward an independent development path. That would require a break with neoliberalism.

Since coming to power, the NPP has pledged to follow the terms of the previous government’s IMF Agreement. It even accepted an Agreement in Principle with external bondholders, which contains unprecedented legal revisions to allow a restructuring of Sri Lanka’s bonds largely to the benefit of commercial creditors. In this regard, it does not appear that the NPP is yet willing or able to resist the blackmail of global capital.

Nevertheless, the NPP cannot be dismissed outright, particularly given the widespread anger with austerity that facilitated the coalition’s victory. The JVP in particular has played a key, albeit contradictory role in the multifaceted history of the Sri Lankan Left. The party, and by extension its electoral coalition, has tended to reflect broader contradictions in the polity. It straddles various class fractions and social groups. The NPP now stands at a critical juncture. Will it address the grievances of an increasingly immiserated middle class and the working people, who have borne the brunt of the current crisis, by pursuing self-sufficiency with a strong redistributive dimension? Or will it fall back on aspirational rhetoric that appeals to its newer backers in the professional and business communities, while sticking to the current economic trajectory?

Critical engagement with the party’s history is necessary to explore if and how the NPP can be pushed to the left – a question that left-wing forces around the world must also ask themselves as they strive to build viable progressive coalitions amidst the unravelling of the world order.

Maoism, Militancy, and Cross-Class Coalitions

To analyse how the JVP came to be what it is today, we must situate it within the historical context of Sri Lanka’s Left. The country’s first official political party was the socialist Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), formed in 1935 before independence from Britain in 1948. The LSSP’s founding leaders were influenced by figures such as British economist and later Labour Party leader Harold Laski during their studies abroad. Yet the LSSP was not only Sri Lanka’s first party, but also the first Marxist party with an explicitly Trotskyist orientation. As political scientist Calvin Woodward put it, in Sri Lanka, Trotskyists (ironically) represented the orthodoxy, while the Stalinists were the renegades. The Communist Party (CP), which emerged as an offshoot of the LSSP, eventually gravitated toward an alliance with its former party, despite their ideological differences. Meanwhile, the Sri Lankan bourgeoisie found its political home in two mainstream parties, the UNP and its breakaway, the SLFP.

The “Old Left”, represented by the LSSP and the CP, grappled with the strategic dilemma of retaining political independence versus participating in coalitions with the left-leaning but nevertheless bourgeois SLFP. The latter won the elections of 1956, ushering Sri Lanka onto a path of state-led development and import substitution policies in conjunction with a nationalist mobilization focused on the Sinhala Buddhist majority. By the 1960s, however, a split formed in the CP. It led to the formation of the Communist Party – Peking Wing led by Nagalingam Shanmugathasan. Soon thereafter, Rohana Wijeweera emerged as the leader of a youth faction that went on to found the JVP.

Unlike the Old Left, the JVP and the broader “New Left” took a very different approach to the question of armed struggle. The JVP drew from a contradictory mix of ideologies, but was chiefly influenced by Maoism. While the Old Left “preached war and practiced peace”, to paraphrase its eminent theorist Hector Abhayavardhana, the JVP took the question of revolution seriously, even attempting an insurrection against the state in 1971.

“Perhaps because of its appeal to a cross-class bloc, the NPP coalition remains a mirror on which a diverse electorate can project its hopes and aspirations.”

The JVP’s break with the Old Left was not only based on a strategic disagreement, however. Rather, it crystallized around tensions specific to Sri Lankan society, especially in the rural South. The JVP embodied different social, linguistic, and generational cleavages within the Sri Lankan polity. Namely, it drew support from youth who primarily spoke Sinhala and tended to come from rural areas, as opposed to the leadership of the Old Left, which had an Anglophone character and cosmopolitan outlook. Meanwhile, the Old Left joined the United Front government (1970–1977) led by the SLFP, in which the LSSP remained a junior partner until 1975. The Old Left rationalized the government’s brutal response to the JVP insurrection, during which roughly 10,000 people were killed.

Dissidents within the Old Left such as Edmund Samarakkody, however, understood the JVP’s popular appeal. Although its ideology was contradictory, it had emerged as a response to the unresolved problems of underemployed youth in both rural and urban areas. Many in the younger generation had been unable to realize their aspirations even under the social-democratic regime of the post-1956 period. In this sense, the party’s base was among underemployed youth who sought employment in the state, but it also appealed to constituencies such as smallholder farmers, who felt that their needs were not being met by left-leaning governments focused more on their urban trade unionist supporters. This cross-class nature would prove to be both a strength and source of the JVP’s fundamental contradictions.

The Left in Decline

Meanwhile, the social-democratic coalition that governed Sri Lanka in the immediate post-colonial decades failed to pursue vigorous land redistribution. That oversight resulted in further impediments to rural mobilization and the broader transformation and development of Sri Lanka’s economy in a direction more capable of sustaining incipient efforts in self-sufficiency. The final nail in the coffin was the global economic crisis of the 1970s, which exposed the weaknesses of Sri Lanka’s model. The West precipitated this crisis through a capital strike, withdrawing its investments in the country and throttling its already-dependent economy.

Indeed, as Sri Lanka’s terms of trade began to deteriorate, the West began squeezing the country by denying foreign investment. It was a punishing response to the change of regime in 1956 and the country’s turn toward the Bandung project and the Non-Aligned Movement. After the election of the United Front government, the West curtailed even multilateral forms of engagement through institutions such as the IMF and World Bank.

On the domestic front, the government’s bloody crackdown fomented divisions within the Left and encouraged key figures and organizations to focus on the question of civil and democratic rights. Meanwhile, within the JVP, members disgruntled with the party’s lack of attention to the national question began to criticize its position on ethnic minorities. This was especially necessary given the JVP’s xenophobic attitude toward the Tamil minority in the Hill Country. In contrast to the Tamil community in the North and East, the Hill Country Tamils were brought over from India starting in the mid-nineteenth century to work as indentured labour on the plantations. The JVP accused them of being a “Fifth Column” for alleged Indian imperialism in the postcolonial era.

Yet such debates and revisions of the JVP’s judgments would only last through a brief period of rehabilitation during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Afterwards, the party went back underground and silenced the critical voices.

Between Neoliberals and Nationalists

The catalyst for this underground turn was the consolidation of an authoritarian right-wing government led by JR Jayewardene. Following the resounding victory of the United National Party in 1977, Jayewardene announced “open economy” reforms. The shift represented a break with the social-democratic regime and committed Sri Lanka to a path of economic liberalization. Shortly afterwards, the North and East plunged into civil war after devastating anti-Tamil riots in 1983 facilitated by Jayewardene’s government.

Proscribed by the government after the riots, the JVP engaged in a second and more brutal insurrection in the South in the late 1980s. Its ostensible reason was opposition to Indian intervention and the imposition of a quasi-federal solution to Sri Lanka’s national question. After its leadership was decapitated during a brutal counterinsurgency campaign by the state in 1989, it resurfaced and entered the political mainstream as a parliamentary party in 1994. Yet it continued to support the Sinhala Buddhist nationalist project. Believing that “the nation” constituted the last bastion of defence against imperialism, the party adopted harsh nationalist rhetoric and built alliances with far-right forces. Essentially, the JVP’s logic was that it had to prioritize protecting Sri Lanka from Western intervention on issues such as wartime human rights abuses before class issues could be engaged.

Eventually, the party became a supporter of Mahinda Rajapaksa, patriarch of the contemporary Rajapaksa dynasty, who won the Presidency in 2005. Rajapaksa engaged in unrestrained warfare to defeat the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), which by then had ruthlessly eliminated their fraternal rivals. His ultimate victory in 2009 came at the cost of tens of thousands of Tamil lives.

Immediately after the war, however, the JVP rediscovered its role as a critic of the government, and became a relatively consistent proponent of democratic rights in parliament throughout the years leading up 2022. Yet it also faced a series of splits. A left-wing split, the Frontline Socialist Party (FSP), promoted struggles in the streets, while the JVP continued to prioritize parliamentary politics. At the same time, the JVP’s own bases of support shifted. The party attracted growing sections of the middle class, including urban professionals, who appreciated a “clean” alternative to the supposedly endemic corruption of Sri Lanka’s political class.

These shifts laid the foundations for the NPP’s historic victory in the 2024 presidential and parliamentary elections. It benefited from growing frustration among the middle class that had become immiserated because of the economic crisis, no less than wide swathes of working people who had borne the brunt of austerity.

Tensions in the Cross-Class Bloc

Perhaps because of its appeal to a cross-class bloc, the NPP coalition remains a mirror on which a diverse electorate can project its hopes and aspirations. Contradictions between different segments of its supporters will surely grow as the NPP takes over government, much as was the case for the Old Left during its encounter with state power. In this context, we must examine the ways in which the NPP has not, in fact, transcended the JVP’s origins, nor the many problems that have long bedevilled the Sri Lankan Left. Indeed, the NPP represents their continuation, albeit in new form.

This is especially true given that, despite its Maoist lineage, the JVP has repeatedly struggled to articulate a clear, wide-ranging programme of redistribution to transform relations between classes and ethnic communities. From its early distrust of the Hill Country Tamils, the party has not addressed the ethno-majoritarian character of the Sri Lankan state. In addition, along with the wider Left, the JVP has not put forward a programme to address the contradictions in the agrarian sector. The agrarian question is crucial given that some two-thirds of the population still claim residence in rural areas. A more robust response would have required an alternative vision grounded in building up semi-autonomous organizations such as cooperatives. Through such rural mobilization, Sri Lanka could have developed alternative methods of accumulation by strengthening linkages between agriculture, fisheries, and industry.

In contrast, economic liberalization since the late 1970s, although supposedly opening up new horizons for middle-class aspirations, has made Sri Lanka increasingly vulnerable to external shocks. This became especially apparent when, at the height of the foreign exchange crisis in 2022, the country was unable to import even essential items such as powdered milk. Consequently, while agrarian issues such as land redistribution remain pressing, they are no longer the only questions on the agenda.

The NPP’s growing base in urban and professional constituencies compels the party to take on political challenges emanating from the sphere of consumption as much as production. This is especially true given that Sri Lanka’s actually existing neoliberal economy, based on tourism and remittances from migrant workers, has revealed so many vulnerabilities since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, how the middle class would respond to such a much-needed shift would depend on the government’s ability to articulate a new vision of the economy that speaks to underlying demands for meaningful work and upward mobility.

Against Elite-Led Compromise

In other words, the NPP has not found an answer to the age-old question of how to consolidate alliances between radicalized layers of the “petty bourgeoisie” and the working class. In this context, an analysis of the political economy of tourism and mega-infrastructure is essential to understand Sri Lanka’s recent development trajectory. They have become conduits for powerful global forces to exercise even greater leverage over Sri Lanka’s economy.

Building a new bloc of social and class forces committed to an alternative form of development requires a clear understanding of the economic challenges should Sri Lanka try and carve out a new path. Structural parameters include not only the fickleness of foreign revenue sources such as tourism and remittances, but also the need to save foreign exchange on imports while producing more exports. Any attempt to re-balance the economy toward a new strategy of accumulation with the goal of building up domestic wealth would have to strengthen linkages between sectors of the economy, such as food production and its corresponding inputs like boats for the fishing community and fertilizer for cultivators. That, in turn, would require active state investment and planning in areas where market actors are unlikely to obtain immediate profits. But it would also demand a political economic approach to balancing the often-contradictory interests of working people in all their diversity on one hand, and middle-class constituencies on the other.

“If the NPP enjoys an initial advantage, it is the extent to which, because of its origins in the Left, it is not predisposed to the vulgar luxury consumption that motivated the ruling-class elites who helped entrench Sri Lanka in relations of dependency.”

What can we draw from the NPP’s history to evaluate its potential to respond to these challenges? Much of the debate on the Sri Lankan Left has been pitched at the level of tactics and strategy. The debate about whether struggle is required in the streets or in parliament has become part of an ongoing attempt to distinguish the NPP from its marginal, radical left rivals. But we need a much sharper understanding of the contrast in the world of ideas to clarify the two paths currently available to the Dissanayake government.

One involves compromise with the comprador elite, accepting the current balance of forces and being resigned to the crumbling, Western-led global order. In the medium term at the very least, this would mean a return to the same trajectory as previous governments, rendering the NPP’s victory hollow. In contrast, the 2024 elections could also go down in history as the precursor to a much bigger push to transform Sri Lanka’s economy. But that would require shifting it onto a new trajectory that reflects a clear alternative to neoliberalism.

If the NPP enjoys an initial advantage, it is the extent to which, because of its origins in the Left, it is not predisposed to the vulgar luxury consumption that motivated the ruling-class elites who helped entrench Sri Lanka in relations of dependency. That said, the NPP’s humble origins and reputation for honest governance are no guarantee that it will avoid disastrous economic compromises due to a combination of short-sightedness, weakness, and apathy.

Should it continue on a path of timid compromise, the JVP and NPP will simply become the latest Sri Lankan face of the obsolete centre-left establishment that has enforced austerity in country after country. To avoid this outcome, the Left must develop a vision that prioritizes social mobilization and transforming the relations of production, as much as it does legal reforms and changes to the structures of governance. •

This article first published on the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung website.