Finnish Capitalism at a Tipping Point: Resisting Racism, Austerity, and Militarism

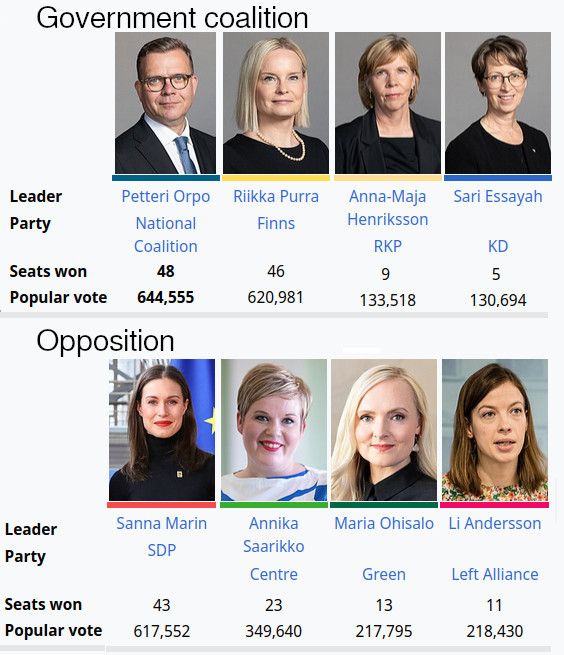

Finland’s 2023 parliamentary election saw the formation of a new government led by Peteri Orpo’s National Coalition Party (NCP), with the True Finns as the main coalition partner. The NCP gained 20.8% of votes cast, the Finns came a close second (20.1% – the strongest result since the party’s founding), and the ruling Social Democrats led by Sanna Marin were knocked back into third place (19.9%). Two smaller parties – the Swedish People’s Party (RKP) and the Christian Democrats (KD) – also joined the coalition, while the struggling agrarian Centre Party (having been part of the previous Marin government alongside the Greens, Left Alliance, and Swedish People’s Party) went into opposition.

Following the coalition negotiations, attention naturally centred on the issue of far-right racism. A far-right ‘populist’ party that achieved its electoral breakthrough in 2011 and spent two decades in opposition before joining Juha Sipilä’s Centre-led cabinet in 2015 (and then returning to opposition following a 2017 split), the True Finns made their mark by ensuring that anti-immigrant policies were incorporated into the Orpo government programme. Such policies included higher income limits for foreign workers, tightened citizenship rules, and slashed quotas for refugees. Several Finns ministers made no secret of their overt hostility toward black and brown-skinned immigrants in particular, their far-right affiliations, and their pro-fascist or pro-Nazi sympathies.

The Finns Party leader and current finance minister and deputy prime minister, Riikka Purra, has previously made a litany of racist and violent statements against immigrants (e.g., using the Finnish equivalent of the ‘n-word’) (Teivainen, 2023). Jussi Halla-aho, the former Finns leader, current speaker of the parliament, and 2024 presidential election candidate, is a militant racist with legal convictions for religious defamation who has called Islam a ‘religion of paedophiles’, claimed that thieving is a ‘genetic trait’ of Somalis, and stated his wish that pro-immigration female MPs be raped by foreigners (YLE, 2012). Soon after the election, Vilhelm Junnila, then minister of economic affairs, narrowly passed a vote of confidence but was forced to resign a few days later after it was revealed that he was a speaker at an event organized by violent fascists – a veritable ‘who’s who’ of neo-Nazis in Finland, including the now-banned Nordic Resistance Movement (Topping, 2023). Such racist scandals facing particular ministers have marred the government from virtually day one.

Building Opposition to Far-Right Racism

In terms of building opposition to the most overtly racist dimensions of the Orpo-Purra programme, there have been numerous public protests and demonstrations. The largest was the 11,000-strong ‘Me emme vaikene’ (We are not silent) anti-racism protest held in Helsinki on 3 September 2023. Such mobilizations have played an important role in challenging what is rightly touted as one of the most right-wing administrations in Finland’s history. But while early optimism was pervasive that the new government’s small majority and tensions among its coalition partners would portend its downfall, these hopes quickly proved illusory.

With the European Union economically and geopolitically squeezed between the United States and China plus the looming prospect of a second Trump presidency to the West and a victorious Putin to the East, Europe’s far-right turn appears to be reaching an institutional tipping point (Varoufakis, 2024). In this unfolding epoch of capitalist catastrophe – where the heightened political authoritarianism necessary to impose a renewed wave of economic austerity following the 2007-08 global financial crisis has tendentially eroded capitalism’s representative political shell from within and paved the way for governing alliances between far-right racists and their neoliberal-centrist enablers, the left needs to decisively break with the terms of ‘free markets’ and ‘liberal democracy’ which have defined its accommodation to neoliberalism since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In the Finnish context, this break requires a clear rupture with liberal and centre-left opposition foregrounding the damage inflicted by the new government upon the country’s ‘progressive’ international veneer. With their singular emphasis on combating the worst effects of anti-immigrant racism and the normalizing of far-right rhetoric, liberal anti-racism and anti-fascism factions entirely eschew the confrontation with underlying structural causes that is necessary for sustaining effective resistance. With this in mind, the current essay highlights two major drivers of the rise of the far-right that have the potential to underpin a revitalized counter-hegemonic politics of the left in Finland and elsewhere in Europe, namely those rooted in capitalist globalization’s relentless march toward austerity and war.

Socio-Economic Roots

Unemployment and inflation are not caused by immigration. Immigrants and refugees do not have the power to alter market prices, under-pay, under-employ, or lay off workers. Such decisions are the prerogative of capitalist employers and the political parties that represent their collective interests by espousing the rhetoric of ‘free markets’. Although multinational capital in particular claims to support the interests of foreign workers in the domestic labour market, this support is entirely secondary to its overarching commitment to advancing the forces of austerity, ‘deregulation’, and privatization. By undermining social solidarity and the welfare state, it is precisely these forces that have fuelled the underlying socio-economic discontent that enables anti-immigrant racism and xenophobic scapegoating to flourish.

In the wake of the 1980s Reagan-Thatcher counter-revolution’s crushing of organized labour and the neoliberal relaunch of European integration in the shadow of US-led financial globalization, successive Finnish governments responded to the deep financial crisis of the 1990s by gradually dismantling the old postwar Nordic welfare state despite its enduring popularity. In its place, a neoliberal competition state was constructed under the aegis of the Ministry of Finance’s central coordinating role in fashioning a national competitiveness strategy as the dominant mode of raison d’état (Kantola and Kananen, 2013; Ahlqvist and Moisio, 2014).

These interests of dominant capital have received powerful expression in the Orpo government’s economic strategy, where the NCP has led the way in championing a fiscal austerity programme that is radical by contemporary Finnish standards in the extent of its attacks on what remains of the labour movement and the welfare state. On the one hand, the Orpo government’s programme entails a full-frontal assault on public provisions that mostly benefit the working class. In this regard, the government pushed forward €6 billion in cuts to public health, education, and welfare expenditure over the next four years – including substantial reductions to and/or stricter means-testing for unemployment benefit, housing allowance, and social security.

On the other hand, the programme is geared toward an all-out confrontation with the trade unions, encompassing direct attacks on workers’ rights, attacks that threaten to undermine the effectiveness of the labour movement over the long term. These measures have ranged from a very unpopular policy to make the first day of sick leave unpaid to restrictions and fines for workers engaged in wildcat or sympathy strikes. They also encompass efforts to localize collective bargaining and afford employers greater leverage within the ‘consensus-based’ corporatist structures through which socio-economic policy in Finland is negotiated between big capital, labour, and the state (Ahponen, 2023).

These attacks on workers’ rights and the labour movement have not gone unnoticed by Finland’s trade unions, which have sought to galvanize opposition to the government programme. The clearest expression of this tendency has been intermittent waves of political strike action (notably those from February-April 2024), which have showcased growing discontent with the government’s neoliberal policies favouring austerity and labour market flexibilization while raising the prospect of a future general strike (YLE, 2024a). But while such actions underline the potential for building an alternative working-class politics rooted in collective struggle, solidarity, and organization amidst the severe ‘cost of living’ crisis confronting Finnish and European workers, the extent and results of this union mobilization have been far too constrained to threaten the survival of the government.

Moreover, the left-leaning debate on opposing neoliberal austerity continues to sidestep the crucial question of the latter’s structural causes rooted in capitalist globalization and particularly European integration as its concrete regional expression. This is especially the case in the wake of ‘Brexit’, where anti-globalization and anti-EU sentiment have become increasingly associated with the growing political salience of the ‘Eurosceptic’ far-right. But a strong argument can still be made that while the EU incorporates some commitments to minimal standards of employee protection, the free movement of workers, and international human rights law, its core institutions – the single market and currency union – amount to a thoroughly anti-democratic project of advancing ‘free market’ capitalism in the interests of big business. Since the mid-1980s, this project has overseen what is effectively a continent-wide structural adjustment programme, contributing to rising unemployment that has significantly weakened trade unions and facilitated the dismantling of national welfare states (Ryner and Cafruny, 2016; Carchedi, 2001; Patomäki, 2013).

Although austerity is primarily implemented at the national level, the Finnish state’s growing international obligations as an EU member state have played a major role in reinforcing the erosion of workers’ rights and social protections. For example, European monetary and financial-market integration has since the 1990s played a key role in restructuring Finland’s labour market by shaping the terms of the Finance Ministry’s neoliberal competitiveness strategy premised on supply-side, ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ policies. This is because the removal of national interest and exchange-rate policy mechanisms within the single market and eurozone result in an institutional loss of macroeconomic policy autonomy. This loss of policy autonomy, in turn, all but ensures that the burdens of macroeconomic adjustment fall squarely on wage restraint and flexibilization in the labour market. In short, all governments – quite regardless of their political and ideological leanings – are effectively bound to a policy of more-or-less competitive austerity, inducing tendencies toward a so-called ‘race to the bottom’.

Alongside this erosion of workers’ rights and social protections, the EU’s embrace of global and continent-wide free trade and capital mobility has resulted in a Europe that is grossly divided between a wealthy ‘core’ and a dependent ‘periphery’. This latter point is well captured by the actions of the ‘Troika’ (the European Commission, European Central Bank, and International Monetary Fund) during the Greek sovereign debt crisis of the 2010s, which the Finnish government actively supported alongside the so-called ‘Frugal Four’ (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden) and other countries favouring EU budgetary restraint and tight fiscal policies in the eurozone (especially Germany and the UK). It is also illustrated by the unequal terms of EU enlargement in central and eastern Europe. Furthermore, instead of combating racism and Eurocentrism, the EU has promoted a ‘Fortress Europe’ that imposes grossly unequal terms of trade on underdeveloped countries in the global South and actively conspires against migrants seeking safe sanctuary from hunger, poverty, and war by crossing the Mediterranean.

And by fuelling the rise of anti-immigrant racism, it is paradoxically EU support for free trade and capitalist globalization that has done the most damage to the progressive European ideal of international solidarity among peoples and nations. So long as this neoliberal policy programme implemented in various forms by successive Finnish governments is justified as necessary for advancing the European project, it will remain impossible to consistently oppose national and international pressures favouring competitive austerity.

A revitalized working-class politics must therefore propose radical and concrete alternatives to the strongly neoliberal format taken by European integration since the 1980s. If European integration is to be salvaged, then there is no alternative but to oppose the EU’s founding principle that labour mobility only matters as a complement to the mobility of capital. Ultimately, this means championing a politics of internationalism from below, one concerned with constitutionalizing workers’ rights, the free movement of people, and the survival of the planet precisely by restricting the freedom of capitalists to move money and resources wherever they please, engage in free trade, and undermine trade unions through globalization.

Geopolitical-Military Drivers

Alongside consistently opposing racism and austerity, defending the rights of migrants and refugees also means standing firm against the imperialist wars through which global capitalism and neo-colonialism kill and displace millions, particularly in the countries of the global South. This includes opposing the growing militarization of society, the use of weapons sales to buttress far-right, authoritarian and dictatorial regimes, and both direct and indirect armed interventions by hostile powers. Not only have militarization and war become major drivers of the global pool of displaced workers that has come to form the backbone of racist agitation in Finland and elsewhere, but they also exacerbate the conditions for far-right, neo-Nazi, and police violence against migrants, refugees, and their allies.

But while it is the case that neoliberal austerity programmes have attracted growing, albeit inconsistent, criticism across Europe, consistent opposition to militarism and war has come under sustained and intense attack in the heated political climate following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Europe’s political centre has converged around the American view that European leaders enabled the invasion by trading with Russia and appeasing Putin. Ukraine’s need for self-defence has been exploited to shore up unconditional allegiance to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), lock in a renewed arms race, and deflect vital opposition to Russian imperialism away from support for peace, diplomacy, and human rights. There is a ‘new McCarthyism’ targeting peace activists, critics of Western foreign policy, and anyone voicing even mild doubts about a strategy of confrontation with Russia and/or China.

In Finland, the issue of militarism has been further aggravated by the country’s specific history of state formation, where tensions between Finnish national aspirations and Russian security interests have loomed large. After being elevated from a Swedish province (1150-1809) to an autonomous nation (‘Grand Duchy’) within the Russian Empire (1809-1917), Finnish national identity developed in opposition to its ‘eastern’ Other. As one former Finnish ambassador to the United Nations and Sweden puts it, “Lutheran Finland with its western values and a legal system and administrative structure inherited from Sweden had no difficulty in marking its separateness from orthodox Russia, living under autocratic rule” (Jakobson, 1987, p. 22).

Amidst growing inter-imperial rivalry after 1870, a reciprocal process of enemy construction ensued as Finnish autonomy clashed with Russian imperial interests in maintaining autocracy at home and guarding against the threat of invasion posed by Germany’s late industrialization. Despite Lenin’s Bolsheviks being the first to recognize Finland’s declaration of full independence in 1917 (following Tsarism’s collapse in the throes of war and revolution), the Finnish Red Guards who took power in Helsinki in January 1918 were violently put down by General Carl Gustaf Mannerheim’s White Army with the aid of a German expeditionary force. Russian fears that Finnish separatism could pave the way for a German invasion were confirmed, while Finnish nationalists came to regard ”Russia, Communist or otherwise, as the permanent enemy of Finland’s freedom” (Jakobson, 1987, p. 27).

As each state’s efforts to increase its security were perceived by the other as a security threat, both sides played a part in creating the enemy they claimed to be reacting to. It would take two Finnish-Soviet Wars (the Winter and Continuation wars) and several other tests before Stalin ultimately accepted Finnish independence and Finns learned to live with oscillating Soviet power. During the Cold War, Finland’s militarily non-aligned foreign policy – the Paasikivi-Kekkonen Doctrine of ‘active neutrality’ – proved crucial to upholding this more harmonious geopolitical settlement. Even after the occupying Western powers revived post-fascist West Germany and integrated it into NATO in 1955 (leading the USSR to retaliate by announcing the Warsaw Pact the following week), Finland was able to successfully balance between East and West as the basis for retaining its independent statehood and building a universalist welfare state.

In this context, the notion of ‘Finlandisation’ that became the West’s conventional wisdom during the 1960s functioned primarily as an ideological stick for right-wing journalists and politicians. This was especially the case regarding German Christian Democratic (CDU/CSU) opposition to Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik, but Singleton (1981, p. 270) also cites a 1979 leading article in Britain’s Sunday Telegraph fearing

“a Left-wing Labour government coming to power that would be prepared actually to cooperate with the Kremlin’s plans for European ‘Finlandisation’. Tony Wedgwood Benn in Downing Street, and Teddy Kennedy – his equal in fatuity – in the White House; from the Russian point of view that would represent a triumph of all the elements of Western intellectual and moral weaknesses.”

Within the terms of this critique of active neutrality as naïve subservience to Soviet aggrandisement in foreign policy as well as economics, politics, art, literature, and culture, Finnish President Urho Kekkonen was thus the archetypal ‘Putin’s Puppet’ of his day – representing the creeping Sovietization/Russification of the West. Such attitudes then provoked ‘great resentment in Finland’, where they were widely maligned as being ‘based on ignorance of Finland’s position vis-à-vis the Soviet Union’ and as bearing ‘no relationship to Finnish reality’ (Singleton, 1981, p. 271).

But with the collapse of Soviet ‘state socialism’ prefiguring the emergence of a greatly weakened and truncated capitalist Russia during the ‘long 1990s’ (1992-2007), the Finnish state’s embrace of neoliberalism entailed an adaptation to American ‘unipolar’ hegemony via pivoting closer to the Western camp. Finland joined the EU in 1995 (along with Austria and Sweden) and cultivated a close partnership with NATO. As the foreign policy ideals associated with Nordic social democracy were gradually eclipsed by the geopolitics of ‘free trade’ and ‘humanitarian intervention’, this decades-long process culminated in the Marin government’s decision to take Finland into NATO and the Orpo coalition’s subsequent signing of a bilateral military pact with the US in 2023 (Hakanen, 2023).

This trajectory ‘from neutral to NATO’ raises serious questions about the small Finnish state’s capacity to safeguard its security in a world of intensifying great-power competition. While Finland’s drift toward NATO was permissible during the ‘unipolar moment’ of American hegemony in the 1990s and 2000s, the subsequent waning of this moment and Russia’s growing independence from Washington in foreign policy make closer military alignment with the US a potentially destabilizing step in the wrong direction. Amidst growing rivalry between Washington and Moscow, Helsinki’s security looks very unlikely to be increased by the permanent military tension and the souring of diplomatic relations that will inevitably flow from being NATO’s frontline country. Indeed, Finland’s previous foreign policy of military non-alignment is ironically more – rather than less – relevant today than when the country began its drift toward NATO.

Furthermore, there are already clear indications that ‘NATO Finland’ has shifted toward a decidedly more militaristic foreign policy, one according less weight to concerns over peacebuilding, human rights, and international law. This is particularly evident in relation to anti-colonial struggles, where the country has been complicit in the violent oppression of the Kurdish people by relaxing restrictions on arms exports to Turkey (a fellow NATO member state) (YLE, 2022). After finalizing a widely criticized €317 million arms deal with US-ally Israel (for the ‘David’s Sling’ air defence system), the Finnish government also abstained on a critical early UN vote over supporting a ceasefire to halt the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza, abstained in a subsequent vote supporting full Palestinian UN membership, and has since remained hostile to the growing Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement’s calls to stem the rising tide of settler colonialism, anti-Palestinian racism, and scholasticide (Duong-Pedica, 2023; YLE, 2023; YLE, 2024b; YLE, 2024c).

This foreign policy shift has proved especially unnerving given that Finland’s NATO accession was rammed through the Eduskunta at breakneck speed amidst a significant curtailment of public debate. Rather than deliberating over the pros and cons of NATO and membership thereof, the focus remained squarely on Finland’s old Russian enemy, which was represented in stark Manichean terms as an ‘evil’ adversary over which ‘good’ Ukraine and its Western allies could only triumph militarily (Lynch, 2023). In this context of visceral but decontextualized analogies between Finnish historical experience and the post-Euromaidan Ukrainian state’s own failure to chart a viable strategic path between the twin perils of submitting to or suicidally resisting superior Russian power, a wide variety of arguments favouring negotiations to end the war or continuing with Finland’s non-aligned foreign policy were summarily dismissed as ‘pro-Putin’, while protests opposing NATO accession tended to be marginal (numbering 500 people at best).

Such curtailment of public debate amidst declining parliamentary accountability has only continued, for example, with the creation of the Helsinki Security Forum (HSF). Describing itself as a ”high-level, invitation-based event, bringing together over 200 decision-makers and international security and defence experts, and influencers,” this secretive forum was first convened in 2022 by the Finnish Institute of International Affairs – Finland’s equivalent of the US Council on Foreign Relations or British-based Royal Institute of International Affairs (Chatham House).1

A world divided into rival military camps led by nuclear-armed great powers is no way forward for humanity. Such a world cannot provide the basis for lasting peace and security or address the existential emergency of climate change. Today, more than ever, a revitalized peace movement is needed to act as a political counterweight to pro-war hawks on both sides of Finland’s eastern border. Such a movement could play a vital role in publicly advocating for an alternative vision of Finland as a neutral third force in world politics, one that is consistently committed to anti-colonial struggles, a revised post-Cold War security architecture (one more conducive to balancing the rights of small states with peaceful coexistence among the great powers), and greater European strategic autonomy vis-à-vis Washington. But in its absence, the far-right looks set to be the main beneficiary once the true costs and implications of NATO membership are revealed – in a manner eerily reminiscent to how neoliberal free-market policies and institutions have spurred the growth of far-right Euroscepticism.

Conclusion

By fusing a neoliberal economic programme with anti-immigrant social policy, the Orpo government represents an emerging political alliance between far-right racists and their neoliberal-centrist enablers. On the one hand, it embodies the waning of the ‘post-political’ neoliberal consensus epitomized by Clintonism in the US, Blairism in the UK, and ‘Third Way’ social democracy in Europe. Alongside supporting NATO expansion and the disastrous US-led post-9/11 military interventions in the Global South carried out under the guise of the ‘War on Terror’, a large part of this neoliberal project during the 1990s and 2000s consisted of attempts to ‘lock in’ and ‘constitutionalize’ pro-market reforms by taking key issues about how the economy and society are governed out of politics.

But since 2008, this neoliberal consensus has steadily lost much of its legitimacy in the context of a multidimensional crisis of global capitalism. In the decade from the global financial crisis to the global covid pandemic and beyond, various ‘morbid symptoms’ of this crisis have included massively growing economic inequality and social exclusion, a new wave of fiscal austerity eroding health, education, and social security, the rise of political leaders openly disdainful of globalization, growing recognition of the climate emergency, the return of ‘stagflation’ (rising unemployment and inflation), and the threat of nuclear war raised by the waning of American ‘unipolar’ hegemony.

In this context of crisis, it has become harder and harder for political and corporate elites to mediate the tension between the requirements of global capital accumulation and the interests of the populations whose votes they need to stay in power. And although the 2010s saw the re-emergence of a fledgling socialist left, the main political beneficiary of this fracturing of neoliberal ‘global governance’ has been the far-right, with the dominant trend being a growing hyper-nationalist backlash that has increasingly upended the political system.

Given this balance of political forces, what we are currently observing in country after country is a dialectical ‘double act’ between the waning neoliberal centre and the rising far right in all its possible combinations. This general tendency is the one that is currently playing out in Finland, albeit with its own national peculiarities and idiosyncrasies.

If there is to be any hope of turning the tide, then it will be necessary to go beyond a one-sided focus on addressing the symptoms of far-right racism. This means beginning to unearth its deeper structural causes rooted in a global capitalist system whose endless prioritizing of profits from exploitation, war, and environmental destruction over human needs is driving working people – and what remains of the ‘middle class’ – into growing poverty, alienation, and destitution. •

Sources

- Ahlqvist, Toni and Moisio, Sami (2014), “Neoliberalisation in a Nordic State: From Cartel Polity towards a Corporate Polity in Finland,” New Political Economy, Vol. 19, No. 1, 21-55.

- Ahponen, Tatu (2023), “Finland’s Neoliberal and Far-Right Alliance is a Sign of Things to Come in Europe,” Jacobin, 17 July.

- Carchedi, Guglielmo (2001), For Another Europe: A Class Analysis of European Economic Integration, London: Verso.

- Duong-Pedica, Anais (2023), “Suffocating the academic and student solidarity movement for Palestinian liberation in Finnish Higher education,” Raster, 4 December.

- Hakanen, Yrjö (2023), “US bases will bring problems, not security,” 14 December 2023.

- Jakobson, Max (1987), Finland: Myth and Reality, Helsinki: Otava.

- Kantola, Anu and Kananen, Johannes (2013), “Seize the Moment: Financial Crisis and the Making of the Finnish Competition State,” New Political Economy, Vol. 18, No. 6, pp. 811-826.

- Lynch, Lily (2023), “Finland’s Turn,” Sidecar, 12 April.

- Patomäki, Heikki (2013), The Great Eurozone Disaster: From Crisis to Global New Deal, London: Zed Books.

- Ryner, Magnus and Cafruny, Alan (2016), The European Union and Global Capitalism: Origins, Development and Crisis, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Singleton, Fred (1981), “The Myth of ‘Finlandisation’,” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), Vol. 57, No. 2 (Spring), pp. 270-285.

- Teivainen, Aleksi (2023), “Purra says her earlier online comments were ‘angry text, nothing else’,” Helsinki Times, 11 July

- Topping, Alexandra (2023), “Finland coalition in chaos as far-right minister quits over ‘climate abortion’ remark,” The Guardian, 30 June.

- Varoufakis, Yanis (2024), “Draghi’s Report Confirms Europe’s Irreversible Decline,” 23 September.

- YLE (2012), “Supreme Court orders Halla-aho to pay for hate speech,” YLE English, 8 June.

- YLE (2022), “Finland relaxing arms export rules to Turkey,” YLE English, 18 December.

- YLE (2023), “Finnish leaders defend abstention in UN vote on Gaza ceasefire,” YLE English, 28 October.

- YLE (2024a), “SAK: Political strikes to end – for now,” YLE English, 4 April.

- YLE (2024b), “Police break up pro-Palestinian protest at University of Helsinki,” YLE English, 13 June.

- YLE (2024c), “Finland abstains in Palestinian UN membership vote,” YLE English, 11 May.

Endnotes

- Participants in the 2024 HSF (held at an undisclosed location on 27-29 September) included the President of Finland (Alexander Stubb) and the President of Lockheed Martin International, as well as the former Finnish ambassador to the US and former US ambassador to Finland, director of the Finnish intelligence service, secretary general of the Finnish defence and aerospace industries (PIA), a representative from the US defence secretary’s office, foreign and defence policy analysts from the RAND Corporation, Center for Strategic & International Studies, and American Enterprise Institute, NATO’s ‘senior mentor for logistics’, the commander of the Estonian military, and the Brussels bureau chief of the Financial Times. Among the Forum’s main sponsors were the Finnish foreign and defence ministries, Helsinki city, NATO, Lockheed Martin, the Fortum and Patria state-owned Finnish energy and defence corporations, IQM quantum computers, and the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats. For more information, see: Helsinki Security Forum (2024).