Fighting for a Better Deal and a Better University: Obstacles and Possibilities for Workers in Ontario’s Higher Education Sector

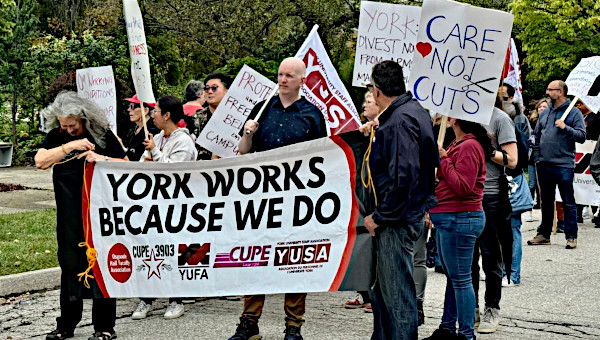

I write as a rank-and-file member of CUPE 3903 at York University, Toronto, who works as a teaching assistant. Our recent round of bargaining and strike action has underscored some of the challenges that face us both as workers in our specific institution as well as in the higher education sector in Ontario and beyond. In particular, there is the nature of the university as a workplace; the ongoing and intensifying assault on democracy and ‘collegiality’ in the university; labour action amidst a historic cost of living crisis; and the questions of strategy posed by these issues and more in combination.

The university poses particular challenges as a workplace to organise and build power within. For one, it is relatively dispersed in several respects. Perhaps obviously, and not especially unique to the university, in physical terms campuses are enormous and workers are spread across them based on department. Temporally, higher education workers are likely to only be present in the workplace for part of their jobs, primarily when they have a class or other scheduled commitments. And even though typically these tasks require in-person presence (with a caveat to follow below), the labour process in the university means they are most likely working on their own most of the time – either in teaching itself or in the tasks of meeting with students, grading assignments and preparing for future classes. These realities of the job have been intensified by the societal shifts caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, with the primacy of remote work and a culture of presence on campus only when absolutely necessary showing no sign of abating. All of these factors pose a challenge to simply knowing who your coworkers are, let alone organising and building power with them.

The Nature of the University

Organising within the university also takes place amidst the intensifying assault on democratic processes within these institutions, the undermining of any genuine presence of ‘collegial’ governance, and ultimately a battle over the nature of the university itself. Is a university a credentialling factory designed to respond purely to the economic imperatives of the day, or is it a place where primarily (but importantly not exclusively) younger adults come to develop their capacities for critical thinking and provide the lifeblood of the wider research work that is undertaken alongside degree education? The former answer, which seems to me unquestionably the position held by university administrations in deed if not in word, is the water in which we swim as university workers. It is essential to understand the relentless drive for more precarious (and thus it is seemingly hoped for more placid) university educators, and the way this shapes negotiations over our contracts.

It is in the shadow of this ideological war waged by administrations and dictated by governments that we must view the struggle over working conditions in its most expansive form. We must recognise that disciplining assaults over what the university is and what should take place within it – most egregiously represented in the present moment by the attack on speech and action in support of Palestinian liberation – as part and parcel of the same processes that drive bickering over decimals of percentages in our pay cheques.

Our recent contract fight took place within the context of the Ontario government’s Bill 124 (now declared unconstitutional, for what that’s worth), which capped public sector pay rises at 1% per year while it was in force. This meant that we were also fighting to recover ground lost in our last collective agreement, which was felt particularly brutally amidst double digit inflation and soaring rental prices over that contract’s life. Pay was the most urgent issue for a majority of our members, and yet mobilisation for a strike when it is so difficult to live a dignified daily existence comes with its own challenges alongside any clarity of purpose prompted by such living conditions. Already being close to the brink financially, combined with a pathetic $300 a week of strike pay from our national union (the same rate paid during our 2015 strike action), means the trepidation that accompanies taking labour action is intense.

One key task for us as militant trade unionists is to recognise the very real effect of such factors, planning and building power in order to mitigate and eventually overcome them in the next stages of our workplace struggle. Uniting a precarious, dispersed and atomised workforce can be done, as the strike action taken this round shows. But continuing to build our power and be stronger next time requires us to situate our struggle outside of the walls of our campus. What form this takes is open to question.

In one sense, the aforementioned atomisation within our workplace is mirrored in the fact that we are bargaining as a portion of a single university’s workforce, rather than one big union on campus, or even one big union across the sector bargaining together. While lessons from places such as the UK tell us that this alone isn’t a solution, it seems clear to me that the narrow focus on bargaining for a single three year contract as a single subset of workers plays into the employer’s hands, and that the path to building our power must lie in broadening the horizon of our fight as a union – both within and beyond our university and the university as a wider institution. •

This article first published by Class, Race and Corporate Power available at digitalcommons.fiu.edu.