Law At Work: Class, Property, Capitalism

This essay is an excerpt from Harry Glasbeek’s new book Law At Work: The Coercion and Co-option of the Working Class, Between the Lines, 2024.

For thousands of years, workers have produced goods and services for themselves and others, sometimes being paid, sometimes not. But, for the most part, workers had few legally recognized political or social rights. Workers were not free, at least not in the way in which we describe freedom in our time. It was not until the late 1800s that the goods and services provided for others by workers in the AngloAmerican jurisdictions (which are the focus of this book) could be labelled to be “free labour.” Today, this slowly developed “free labour” is deemed to be an essential, an indispensable component of the variety of capitalism that has established itself in these jurisdictions. This book focuses on the ways in which law in these jurisdictions has moulded and shaped the nature of this “free labour,” asking what it purports to be, might have been, and actually is.

Before we arrived at capitalism, there was feudalism. The movement to break away from feudalism took close to three hundred years before it became evident that feudalism had had its day, that a profound regime change had emerged. During this long period, workers’ lives were controlled by their masters, by their lords. It made sense to have laws which could command them to work, for whom they must work, that permitted masters to punish them as criminals for being negligent or for refusing to abide by orders issued by masters. Even as feudalism was tottering toward its end, slavery was still permitted in Britain (whose laws and practices imbued those of the jurisdictions under examination here) and in its many colonies. Freedoms of the kind which we think of as normal today had no place in a system which explicitly gave legal rights to some and not to others, to owners of land (and to some very few specified others) and none or virtually none to all others. Workers’ lives were truly miserable lives.

Emergence of Capitalist Relations

Eventually, a new set of relations of production did emerge. Historical developments are not linear and, necessarily, some of the characteristics and features of the prior order persisted. The passing of feudalism and clear emergence of capitalist relations of production signalled, however, that in the main, the long, long period of unfree labour had been replaced by a system which was radically different. Now the conditions of producing workers were to be regulated by private contract-making, a scheme hailed as a great advance for the working class.

Elites and intellectuals jumped on the bandwagon as the new status quo was perceived to have been nailed down. Indeed, they seemed nonplussed by the fact that the merits and benefits of the new political economy had taken so long to be appreciated. By the middle of the 19th century, these gatekeepers were hailing the now established regime change as an inevitable and progressive change. In 1861, the English legal historian Henry Maine observed that what had occurred was a transformation of a system of social relations based on status to one founded on contract, that is, on personal choice and endeavour. This was an unalloyed good. Under feudalism, individuals’ rights, duties, obligations, and privileges had stemmed from their relationship to landowners or to their attachment or lack of attachment to a merchant or craft guild. Their personal talents, their inherent drive and capacities, could not change their standing, their place in society. The fundamental change that the advent of capitalism had brought to individuals was that their talents and endeavours mattered. It was incontrovertible to the 19th-century observers: the turn to capitalism heralded the dawn of a new freedom.

This opinion became deeply embedded and, despite some increasingly discordant murmurs to the contrary, the prevailing view still is that capitalist relations of production are the terminus of political economic development, a final plateau. There is no need for theorists and malcontents to look for a new regime, no need to think about working toward a fundamental change in social relations. The system is widely believed to be capable of sustaining individual political and economic freedoms and producing material welfare better than any that went before it and better than any other that might be conceived. There Is No Alternative (TINA), proclaimed Margaret Thatcher. Intellectuals were eager to affirm this view. Thus it was that Francis Fukuyama’s claim that the end of history has been reached was hailed as an obvious truth. Of course, the well-informed cheerleaders for capitalism are always mindful that, on the ground, things are not always what they should be. They, Fukuyama included, acknowledge that, at any one time, the practice of capitalist relations of production may not deliver as much freedom or as much welfare as its logic promises. The early part of the 21st century appears to constitute such a moment.

There are an increasing number of anti-capitalist protests, many in very mature capitalist societies. These uprisings are spurred, in part, by the gigantic gains in income and wealth by the few and the corresponding stagnation of income and wealth for the many. A sense of being left behind by those who, only recently, had been reasonably well off, is common. In 2015, Oxfam reported that 62 individuals owned as much wealth as the poorest 3.5 billion people in the world; in 2018, Oxfam reported that a mere 27 billionaires had as much wealth as the 3.8 billion people on the bottom rungs of the world’s wealth ladder. David Macdonald, the senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, reported that, in 2014, 86 people, 0.002 percent of Canada’s population, had more wealth than 11.4 million Canadians. In Australia, Oxfam showed that the top 1 percent owned as much wealth as the bottom 60 percent of the population. A Global Wealth Report documented that three-quarters of the world’s population owned less than 4 percent of the world’s assets. And the well-known environmentalist and political philosopher Jeremy Lent claimed that 2,754 billionaires owned $9.12-trillion worth of assets, making them, as a group, the third-wealthiest economy in the world, behind only the US and China and ranking ahead of the combined gross domestic product of Germany and Japan. There are a host of like reports, leaving it undoubted that inequality has risen exponentially in the last two decades.

The wealthy are becoming more easily visible and are becoming a target for the dispossessed. As they protest, the afflicted hold the already rich culpable for the onslaughts (often dubbed “austerity measures”) on workers’ organizations and on the social wage and, therefore, responsible for the widening chasm between the few and the many. In its 2018 report, Oxfam noted that the wealth of more than 2,000 billionaires had risen at the rate of $2.5-billion per day. Oxfam calculated that, should governments impose a 1 percent wealth tax on these wealthy people, there would be enough money raised to educate every child in the world currently not in school and to provide health care services that would prevent 3 million deaths per annum. This is not happening. To the contrary: governments, persuaded that there is no alternative, continue to cut the social wage of the non-wealth owners.

It is hard not to be aware of the palpably increased anger of large swaths of the population. This leads to earnest pronouncements about the need to make some adjustments. It is appreciated that social cohesion may be under threat. News reporters, academics, and political analysts publicly express the worry that austerity policies may give rise to potentially uncontrollable political backlashes, to revolts against the status quo which these worriers still believe to be superior to any other regime. This pushes some pro-capitalism advocates to plead for a return to more gentle capitalist days. They are thinking of the form of capitalism that emerged in economically privileged nation-states during the post–World War II period, a period which the economist Jean Fourastié revealingly labelled Les Trente Glorieuses. During that time, the working class’s share of the gross domestic product grew to be greater than it is now. Both wages and the social wage kept pace with, or bettered, economic growth. It is logical, then, that the machinery used to mediate capital-labour relations in those days is looked to by some who want to avert the backlash to the current malaise. Other would-be saviours of capitalism do not think a mere return to the arrangements of those times will be sufficient to restore order. They see a need to turn to novel wealth-creation methods that would avoid the visible downsides of contemporary capitalism. They argue that non-wealth owners should be given a greater role in decision-making, that there should be a more inclusive political economy. But, of course, they do not envisage a regime that would fundamentally change things; they want to maintain and perpetuate the structure and ideology of capitalist relations of production, even as they avert some of the more horrendous outcomes of its natural workings.

These debates and discussions among some of the most respected guardians of the status quo are sophisticated and revealing. They demonstrate that it is understood, not only by affected workers but also by many perceptive capitalists, that the current dominant paradigm is not delivering as much material satisfaction, political freedom, or personal sovereignty as its many stout protagonists believe it should. Their integrity requires them to hang on to their convictions; they need to believe that this is an aberrational moment which a few reforms could and should rectify. They are wrong.

The claim made in this book is that the promise that a capitalism based on private property rights and freedom to contract would set people free was always false and that those poor outcomes which we are currently seeing are not aberrational results but, rather, are built into a regime that inevitably reproduces and deepens economic, social, and political inequalities. The argument is that, inasmuch as the change from status to contract bestowed new freedoms, they were peculiar kinds of freedom for those who did not own any wealth other than their personal capacities. They had become free to sell their personal capacities, that is, their intellectual and physical attributes. They were free to sell part of themselves. Workers were thus empowered (a strange word to use in this context) to provide for their own needs. All they had to do was to hawk themselves in return for a wage. This freedom made it necessary for others to have the legal right to purchase their personal capacities. Those others were the owners of the means of production. Their purchase of what was on sale entitled them to use what they had bought as they saw fit, just as if it was any other commodity they owned. The purchasers were empowered (now the word seems more apposite) to deploy other human beings’ talents and attributes to suit their ends, not to achieve the goals of those who possessed the talents and attributes. More, as Douglas Hay and Paul Craven document, from early on, the freedom to contract to sell one’s talents was circumscribed by employer-favouring Master and Servant laws that gave the owners of the means of production even more bargaining power than their wealth already gave them. The free contract realm was rigged to favour the already rich. Put in these stark terms, it is clear that, from its beginning, the evolving freedom-to-contract regime was problematic. The liberty bestowed was, well, not so liberating.

To put it more bluntly: the implication of allowing would-be workers to sell their emotional and physical capacities to another, that is, to sell some of the very things that make each of them a sovereign, a special individual, entails the creation of a legalized right of the purchaser, of the would-be employer, to “lord it over” the seller, over the would-be worker. The somewhat jarring expression “lord it over” is used here to draw attention to a continuum between feudal relations of production and the capitalist regime that slowly, but surely, came to replace it. From our contemporary perspective, one of the more brutal facets of feudalism was the legitimacy of the feudal lord to exercise authority over the bodies and minds of his subjects. The Master and Servant Acts provided a bridge between the old regime and the emerging one in that the right to subjugate freed workers to their non-feudal masters’ demands permeated these statutes. If the claim was to be credible that contract-making should be welcomed because it freed people from the limitations imposed on them by the rigidities of a status society where their talents and capacities did not matter, the new regime should have jettisoned any notion that one party to the liberating contract should be deemed legally superior to the other when it came to the deployment of that other’s talents and capacities. This did not happen and has never happened. To thinking pro-capitalists, this is a telling criticism of capitalism. They need a riposte and the more ingenious among them provide it.

An elaborate argument is proffered by capitalism’s protagonists to the effect that what seems to be a modern (greatly softened, to be sure) replication of the feudal lord-serf relationship is not a legally imposed superior-inferior relationship of the kind that feudal law mandated. Rather, the arrangement between employers and their workers is the result of voluntary agreement-making between de jure equal parties to the agreement and, therefore, not offensive to the principles of freedom of contract and liberal philosophy. The influential conservative scholar Ronald Coase describes the employment contract not as one that hands unaccountable powers to the employer but as one that circumscribes those powers as the employee “agrees to obey the directions of an entrepreneur within certain limits.” As will be seen in several of the chapters that follow, this is an implausible characterization of employment relations.

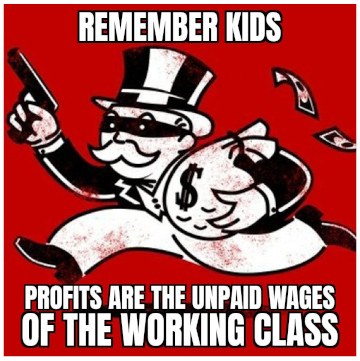

There is another difficulty to overcome for the defenders of capitalism as they claim that freedom to contract should be seen as a liberating concept. From the beginning, the understanding was that the product arising from the use made of the workers’ talents and efforts belonged to the purchaser of those talents and efforts, that is, it became part of the assets, part of the capital, owned by the capitalist. Workers were to be alienated not only by reducing their capacity to determine how their personal abilities were to be deployed, but also by the denial of rights to the product of those uses of their talents and abilities. It is natural that this alienation will produce resentment in the actual producers of goods and services. That kind of resentment, we shall see, was central to many historical struggles waged to resist the advent of capitalist relations of production.

In essence the argument that runs through this book is that we cannot look to the contract-based capitalist system to be a road to freedom, to self-fulfillment and contentment. Robust vestiges of feudalism remain embedded in the new regime. Social relations have not been completely transformed. Capitalists, driven by the profit motive, devoted to the private accumulation of socially produced wealth, depend on keeping the working class vulnerable and oppressed. This is an ideological danger to capitalism’s relations of production as it seeks to retain its dominance, its hegemony. It may not appear to be as benign as its claims to enhanced liberty advertise it to be. Capitalism searches for, and finds, means to keep the overlap between the feudal status-based oppressions and contract-based freedom regimes out of sight. This work argues that law plays a significant role in these procapitalism politics.

This books sets out to show that the ruling concepts of property and contract are foundational ideas and that law embeds them in its version of the Rule of Law and the rules of law that implement it. In this way, law not only provides the basic needs of a capitalist system, but also makes those ideas and ideals commonplace, turns them into notions that are not to be challenged directly. Thus, not only does the law furnish capitalist relations of production with their structural needs, but it also supports them by making them ideologically acceptable. This is quite a feat. The built-in inequality on which capitalism is based leads to inevitable resistance to the outcomes of bargains struck between owners of wealth and the propertyless. As already noted, periodically, in limited locales, the outcomes for those without wealth are not so harsh, and, for that moment in time, relative peace and quiet may reign. But sooner or later, the rapaciousness of those who own the means of production, aided by the privileges and advantages bestowed on them by law, leads to hardships that spawn angry reactions. This is why there is a never-quite-stilled threat to the legitimacy of the regime. For capitalism to be successful, shows of inevitable resistance have to be contained, relabelled, and marginalized. In addition to its structural and ideological roles, law comes to the rescue. Instrumental laws are enacted (a) to facilitate and promote capitalism’s workings and (b) to constrain its excesses.

Law has to fetter capitalists to some extent lest (to use a phrase used by Nick Hanauer, a self-proclaimed out-and-out capitalist) the dominated classes pick up their pitchforks and thrust them, pointy ends forward, at the privileged owners of wealth. There were (and are, as will be seen) many situations that raise this kind of anxiety. One old “for instance” is provided by Danuta Mendelson in The New Law of Torts (2007). She records that, in the mid-19th century (by which time capitalism was firmly in the saddle in the United Kingdom), 50 percent of children in some industries had lost fingers and/or had their hands crushed; by 1854, in some of the larger factories, up to one-fourth of employed children were seriously crippled or deformed. There are many modern equivalents, such as the horrendous toll exacted by asbestos poisonings or explosions such as the one at Bhopal in 1984, the collapse of an eight-storey building in Bangladesh’s Rana Plaza in 2013, or lead or vinyl chloride toxicities, mercury spills, and the numerous deaths in mines and on oil platforms everywhere. These kinds of outcomes repeatedly call the regime’s legitimacy into question.

Efforts to avoid these revelatory failures must be seen to be made. Any such exercise has to marry several competing objectives. Law has to encourage private wealth owners to invest their property to generate more wealth; it has to pacify non-wealth owners by restraining capitalists but not so much that it discourages them from investing and, more importantly, not so much that it brings into question the fundamental right of private property owners to do as they choose with their assets, or not so much that it might erode the sanctity of voluntary contract-making. In sum, to help capitalism, law needs both to promote and restrain the animal spirits that animate its capitalists, a delicate task.

Governmental interventions that fetter the right of the owners of the means of production to do with their property as they choose are portrayed and are largely seen as unnatural or, better, as shackling natural freedoms. They need to be justified. Thus it is that most restrictions are imposed when the harms inflicted by profit-chasing capitalists are grave and have become embarrassingly visible. At such moments, capitalist activities become politically damaging. The government’s intervention is often focused, almost laser-like, on the most recently revealed troublesome sore spot. Frequently, then, the scope of regulatory protection is limited to specific people or groups. For example, the plight of children reported by Mendelson led to early legislative protection for children, not applicable to adult males (although equivalent ones were designed somewhat later to safeguard adult women). This leaves many similarly placed people who do not fall within the definition of protected zones or activities as “unregulated” producers of wealth, that is, they remain unprotected by positive, interventionist laws. The contention in this work will be that this non-protection, too, is a form of regulation: these workers are thrown onto the mercy of unfettered or less fettered capitalist relations of production as constituted by law. The existence of such “unregulated” spheres helps owners of wealth to exercise more power over all workers. Law’s burdensome task is to make all this look normal, natural. The argument here is that this forces law to distort itself, always leaving it open to victims of capitalism to argue that it is an unjustifiable regime.

Law at Work contends that we cannot look to the contract-based capitalist system to be a road to freedom, to contentment. It has not been that because, at its core, it entails oppression and alienation. It cannot be meaningfully reformed, as the many efforts to ameliorate its adverse impacts and subsequent manifestations of their failure illustrated in this work will show. The conclusion is that, as law is designed to keep the scheme in place, the mitigating and legitimating reforms it periodically offers are always limited ones. They embed the very assumptions and beliefs that capitalism needs to thrive. The chapters that follow – and the accompanying online notes – are written, then, to argue that legal reforms are not enough: the regime needs to be rejected if human beings are to attain their full potential as sentient beings.

Essential Workers

If a man had money, he was free in law and in fact, and if he had no money he was free in law and not in fact. — John Galsworthy, The Forsyte Saga

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose

As this is being written, the coronavirus pandemic is still going strong and worrying societies. Of course, it is by no means the first time the world has suffered a pestilence, and it is intriguing that, while technologies have made a difference, there are great similarities between the coping mechanisms developed several centuries ago and those favoured today.

In 14th-century Venice, the locals were ignorant about germs, bacteria, and viruses. There was none of the science, on which we claim to rely, to follow. But when the plague hit Venetians, they quickly realized that the infections spread very quickly and, frighteningly, did so in some invisible way. It made sense to them not to breathe the air that might carry whatever was affecting some people in their community. Touching them was to be avoided. They moved those already afflicted to a separate island to be treated, and any new visitors to Venice were also to be detained there for a given period, forty days; “quarantina,” they called it. The people on the island were to be treated and the carers were equipped with those fancy masks whose replicas are now sold in Venetian souvenir shops. The idea was to ensure that as few people as possible would come into contact with infected or potentially infectious people, and that those who had to deal with them would have to share as little of the ambient air around them as possible.

Today, we have developed tests which detect the presence of virus in people not yet obviously afflicted, enabling us to isolate them and to locate people with whom they may have been in contact. And we have vaccines which help us develop antibodies which will ward off the worst impacts of infections. We still mask and try to practise social distancing and force people out of circulation when they are endangered or might endanger others. We also lock down our borders to keep out visitors who might bring the disease with them. There have been some advances, but the core approach is remarkably similar. And our coping mechanisms are like those of the 14th century in other ways as well.

As noted in chapter one, when the Black Plague hit England in the mid-14th century, the rich and powerful enacted a law which required all the non-rich and powerless to work, whether they wanted to or not. The Statute of Labourers of 1351 made it compulsory for all men, women, and children who did not own land or have a recognized status as a craft, trade, or merchant guild member to work for any owner of land at wages that prevailed before the plague had decimated the population.

Our parts of the world have responded in a less draconian but not dissimilar manner to COVID-19. The strategy has been for governments to decide which businesses are essential to public welfare and then classify those who work in those businesses as essential workers. While, unlike 770 years ago, it is not a criminal offence to refuse to work if deemed essential, governments can and will withhold welfare benefits from such rebellious workers, leaving them to their own devices. Most have little savings, if any, and, without any source of income, would quickly find themselves unable to meet their needs if they refused to do work which has been deemed essential. The bottom line is that they have been given a false choice, a quintessential Hobson’s choice, a choice between accepting something they do not truly want or getting nothing. Workers deemed to be essential workers are being coerced. While this kind of coercion is not, conceptually, the same as the authoritarian decree found in the 1351 law, it does approximate it, rather unnervingly so. This should worry those who claim adherence to a liberal polity and legal system.

Capitalism: Neither Feudal Nor Liberal

The feudal lords who used law instrumentally to compel workers to serve them justified this exercise of power in the long preamble to the statute by pointing out that, as close to half the population had been felled by the pestilence, there was no one to herd the cows and sheep, to seed and till the soil, to pick the fruit, or to harvest the crops. It was not a consumer society, and these listed agricultural productive tasks were pretty well all people did by way of work. If these tasks were not done, the essential needs of society would not be met. This reasoning was used as a justification by the powerful to coerce the less powerful. Of course, it was more than a little self-serving. The lords had no intention of doing that necessary work themselves. It was imagined neither by them, nor by anyone else, that they could be expected to do so. After all, this was a society built on status. The duties and obligations of people depended on their relations to the ownership of land and to landowners, or on their being members of a craft, trade, or merchant guild. Everyone had a status which they could not change, their personal talents and efforts notwithstanding. Under feudalism, some people were legally classified as being politically inferior to others, and it made legal and political sense to require them to serve their superiors. This is a major difference between a liberal polity and a feudal one.

At the heart of liberalism is the belief that all individuals are free to think and act as they choose. No one is to coerce them into thinking or doing anything they would not choose themselves. The autonomy of politically sovereign individuals is what liberalism promotes. This political and legal standing is to be constrained only inasmuch as it is necessary to do so to allow a society to function; no more. A minimum of political interference with individuals’ decision-making is the starting point.

Capitalism, claiming it is based on the functioning of unfettered markets, allies itself with these principles. For markets to operate, each of us is to be able to choose what we want to make and exchange with others who are doing the same thing. We are to use our assets as we decide, on the basis of what we believe is in our own interest. If we are all left free to do this, we should, in the long run, be able to satisfy our needs and desires as we, as individuals, formulate them. Again, a minimum of political interference is the starting point.

It follows that the declaration that, during the current pandemic, some workers should be deemed essential and, therefore, must work for their employers is precisely the kind of political intervention that requires justification. It turns out that it is much harder to accept the justification on offer than the one proffered by feudal barons. They, it will be remembered, asserted that the lack of willing workers had created an existential crisis, that the very survival of society was in play. Some of that is also true today: some food, clothing, water, electricity, and the like need to be provided. But we have not stopped there. To make the point, I offer a sampling of the Ontario regulation that specified what could remain open, what could remain open subject to some constraints, and what had to be closed.

Open and subject to some rules were: supermarkets, convenience stores, indoor farmers’ markets and other stores that primarily sell food, agriculture and food producers, resource and energy suppliers, community services (which meant utilities such as sewage and water provision, health care, and social services), pharmacies, discount and big box retailers that sell groceries, stores that sell liquor, including wine and spirits, gas stations, construction, snow clearing and landscaping services, security services for residences, businesses, and other properties, domestic services, courier, postal, shipping, moving, and delivery services, funeral services, staffing services providing temporary help, laundromats and dry cleaners, veterinary services, boarding kennels, trainers of service animals, cheque-cashing services, financial services, real estate services (but no open houses), telecommunication and IT infrastructure / service providers, newspapers, radio and television broadcasting, film and television postproduction, visual effects and animation studios, book and periodical production, publishing and distribution businesses, commercial and industrial (but not retail) businesses, some entertainment venues, businesses that supply any of the businesses permitted to remain open, maintenance and repair and property management businesses, transportation services … indeed, it seemed as if hardly anything was completely closed. Thus it came about that in the Greater Toronto Area, 67.5 percent of workers were categorized as essential workers, as workers expected to do their jobs as if there were no pandemic.

A much shorter list was the one which provided what was to be closed with only tiny exemptions. It included museums and cultural amenities, horse-racing venues, nightclubs and strip clubs that do not serve food and liquor, zoos and aquariums – although the animals could be cared for by some essential workers – amusement parks, water parks, bathhouses and sex clubs, tour and guide services, motorsports, casinos, bingo halls, and gaming establishments.

What could possibly justify the political coercion of so many people to work during the current pandemic, given that so many worked in spheres which did not have much to do with survival, with ensuring the biological survival of people? While the Black Plague statute did serve the interests of the lords and barons, it manifestly supported life itself, not just convenience. This is hardly true of, say, animation studios, or television post-production or the completion of yet another tall tower or the maintenance of kennels. The question should become more troubling once it is understood what deeming workers essential actually meant to the workers.

First, it is worth identifying who they are: personal caretakers, custodial staff, nurses, paramedics, doctors, agricultural workers (many migrant workers on special visas), teachers and cleaners, caterers, and other workers in education, meat-packing workers, construction workers, retail store shelf-stockers, cashiers, warehouse and storage house workers, couriers and deliverers of all kinds, truck drivers, train, streetcar, and bus drivers, transport maintenance workers, garbage collectors and sorters, mail sorters and carriers, guards and their prisoners who work. All were asked/coerced to take tremendous risks. All of them come into contact with fellow workers, with people who move on public transport systems, with their own families, some of whom may well work in essential services themselves or have to go to schools. Very few of them have paid sick leave entitlements, which makes it hard for them to stay home when they feel ill, intensifying the risk of spreading the disease.

Second, and totally unsurprisingly, the workers affected are disproportionately women, racialized, recent immigrants, and residents of the poorest parts of any city. It took a while for people to come to grips with the fact that it was the most marginalized among them who were being asked/coerced to bear the brunt of the coronavirus pandemic. The truly rich and powerful – leaders of great corporations, military leaders, judges, eminent political figures, financial investors, hedge fund managers – if they worked at all, did not have to mingle much, if at all, with the at-risk population. This was also true of many workers who, while designated as essential workers, could work from home. To them all this was a nuisance and inconvenience, but not an existential threat. Being asked/coerced to work had nothing like the impact on them that such asking/coercing did on the bulk of essential workers. Marxist geographer and theorist David Harvey put this colourfully:

“The virus, it is said, does not discriminate. Well no! Like the New York Times Editorial Board, I live comfortably isolated at home drawing my salary, dependent upon a segregated workforce that has to grapple with the existential choice between eviction and starvation through unemployment on the one hand, or keeping the city and its networks of care and comfort running for a measly wage on the other. And they also have to confront a potentially deadly virus on a daily basis. In what zip code do those workers reside? And what proportion of them are people of color, recent immigrants, Latinos and Latinas? How many laptops do the kids possess?”

The data already gathered answer the questions Harvey poses. Those sectors whose operations suffer disproportionately – such as accommodation and food industries, information, culture and recreation sectors, and wholesale and retail trade – employ more racialized female workers than other sectors. If deemed essential, their health risks are increased and so is the likelihood of losing their not-verywell-paying job. Indigenous people also find themselves in this double whammy position, as the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives reported. An exposé of the plight of migrant farm workers in Ontario (to be discussed in chapter twelve) found that the crowded accommodation conditions, accompanied by uncaring employers, had led to spectacular rates of infection; 196 of the 220 workers at one farm tested positive for COVID. Arianne McNeill reports on studies that showed that, during the first year of the pandemic in the US, working class people had suffered five times as many deaths as had college-educated people; worse, 89 percent fewer people of colour would have died if they had had the same death rates as white college graduates. And the US Poor People Campaign produced a study of 3,200 counties which demonstrated that death rates were twice as high in the poorer counties. During various phases of the pandemic, poorer counties’ fatalities jumped to five times those experienced in the better-off locales.

In a class-divided society, whether it be a feudal or a liberal capitalist one, it is the subjugated class which has to bear the burden of economic and health and safety risks. The pandemic made this clearer to more people than it usually is. Indeed, the pandemic illuminated other aspects of the uneasy relationship between liberalism and capitalism.

Capitalists’ Needs Are Not People’s Needs

In a liberal democratic polity, elected governments are charged with ensuring the general welfare of the population. Thus it has been governments which have decreed what goods and services must be delivered during the pandemic. The bases for their decision-making about what and who they think important reveal much about the kind of polity they actually help to maintain and perpetuate and how they see employer-worker relations.

There are goods and services which governments provide directly or in whose provision they play a large, most often a determining, role. Health, education, and policing come to mind; governments classify them as essential services. But their interventions do not stop there. In societies such as the Anglo-American ones, governments are wedded to the idea that the private sector, driven to pursue profits by competitive forces in a market setting, will deliver what people need more efficiently than any government could. Governments have internalized the mantra that, as government decision-makers are not informed by demands made in a free market economy, they are not well positioned to know what people want and need. Thus it is sensible, they believe, for governments to decree some privately delivered goods and services to be essential. This starting point leads to some awkward issues for elected politicians as they make decisions. How do they determine which privately generated goods and services are essential in the same way as government-produced ones?

Capitalists, unlike governments, do not produce goods and services just because they are needed. To the contrary: their chief concern is whether the production of a particular good or service will yield the best return on any one investment. The potential for profit is what guides capitalists; other considerations are of little account. Capitalists are under unrelenting pressure to generate profits. This forces them to expand markets, in both size and kind.

The intensification of the privatization of what used to be governmental production of goods and services, by means of outright sales, outsourcing, and public-private partnerships, is part and parcel of these ceaseless searches for new areas in which profits are to be found. For-profit actors are increasingly doing things which governments traditionally deemed essential to the welfare of the populations they govern. As governments reduce their direct delivery of services or goods, their reliance on the private sector deepens. The acceptance of the idea that this devolution, this reduction in government functions, is inevitable and, indeed, the way it should be enables politicians to indulge what may well be their instinctive preference, namely to support and applaud the owners of the means of production, as they make their bid to be seen as central to the provision of societal welfare. This puts us all on a slippery slope, one which leads to the establishment of a more fragile, a less secure, society, and one in which notions about what people need become ever more fuzzy.

Capitalism’s logic drives capitalists to manipulate people into demanding more goods and services. Capitalists encourage consumerism, they work hard at making people desire ever more goods and services, to make people feel that they really need them. The late Canadian political scientist Michael Lebowitz captures it well:

“Advertising to create new needs [is] … everywhere. The enormous expenditures in modern capitalism upon advertising, the astronomical salaries offered to professional athletes whose presence can increase the advertising revenues which can be captured by mass media – what else is this (and so much like it) but testimony to capital’s successes in the sphere of production? Those commodities must be sold – the market must be expanded by creating new needs.”

Business affairs journalist David Olive has described the emptiness of it all by defining advertising as “words and pictures, often set to music, designed to correct the mistaken impression among consumers that their lives possess meaning in the absence of a receipt for a particular product in their sock drawer.” And it works.

This boosting of markets by creating demand for things which affect lifestyle but do not add – indeed, may subtract – from the capacity to survive, characterizes our modern capitalist political economies. Who needs tobacco to live? Alcohol? Soft drinks with addictive chemicals in them? Appliances which will obey voice commands so that we do not have to switch on a light or touch a control on our equally unnecessary television sets? Or a gadget that enables us to determine how many steps we have taken today? Or the running of car races by profit-seekers selling polluting oil and promoting private transport in dozens of cities? Or perfumes or deodorants or hair curlers? Or the stock markets where people buy and sell betting instruments, sardonically called financial “products”? Or recreational guns? etc., etc.

Confusion is created. What people need to survive, quite literally, and what they think they need because of the importance they attach to what capitalists have taught them to believe is essential to their lives is blurred. The word “needs” has been given distorted, but widely internalized, meanings. In this context, the long and ever-changing list of what various governments declare to be essential services and undertakings makes some sense; it is inevitable that there will be controversy over the compilation of the list. It helps explain why inconsistencies are built into any set of declarations that some activities are essential, leading to envious cries of discrimination by those not labelled essential or subject to more restrictions than very similar businesses. Much depends on whose ox is being gored. This brings out a point about the differential way in which we treat workers and their potential employers.

During a pandemic, businesses want to stay open. They want to continue to make money. They want to be declared essential. If their plea succeeds, employers win. Workers lose. Owners (and often the legal owner is non-human) run little to no risk of being struck down by the virus. Workers run a great deal of risk if employers retain the right to operate as close to normal as possible. Governments have not been shy about imposing those risks on them.

Governments do so, in part, because, as seen, they find it hard to distinguish between the absolute needs that people have and their desires for convenience and consumption satisfaction. This confusion makes it seem as if anything that the owners of the means of production do serves some public need, and so workers may be asked/coerced to do their bit. In addition, governments are minded to think in this manner because it fits in with their vision of what a liberal capitalist democratic polity holds dear. They are ideologically committed to furnish capitalists with what capitalists need to be effective capitalists. And what capitalists need (and want) is to have as much freedom as possible to determine how they will satisfy their drive for private accumulation of socially produced wealth. Governments are there to protect their right to invest their property in whatever way individual owners decide is best for them. The belief is that this serves the overall good. But that accumulation model favours growth in wealth as it is measured quantitatively, not qualitatively. It is an economic model which privileges growth in monetary terms; it eschews the idea that there might be an alternative, a model which might reduce monetary wealth but keep more people alive and healthy. The way in which Anglo-American polities have been dealing with the pandemic illustrates how their starting point allows the owners of wealth to be helped to be profitable while workers are sacrificed.

Governments have allowed capitalists to externalize their costs while normal business is interrupted. Employers have laid off masses of employees, leaving their survival to the ministrations of governments. That is, governments, all to different extents, have stepped in to provide people with income that the private system, despite the claims made on its behalf, cannot guarantee. More, some employers have been given direct subsidies to continue to employ some workers, even though their operations are down. Even more telling is that our kind of governments are so keen on keeping the normal private competitive economy going that they are willing to allow businesses to remain open until the number of illnesses and fatalities overwhelm the hospital and eldercare systems. And not to put too fine a point on it, most of those succumbing to disease and death are workers who have been asked/coerced into working. “Essential” workers are disproportionately sacrificed. In sharp contrast, little is demanded of the owners of the means of production.

While there are a myriad of governmental interventions to ensure that the owners of the means of production can operate as close to normally as possible, governments have not felt themselves compelled to ask capitalists to do anything they do not choose to do. Governments respect the fact that capitalists do not want to be told how to use their assets. While workers are sought to be placated by slogans such as “We are all in this together,” and they are told by editors, politicians, and pot-banging householders that they are admired for their (asked-for/coerced) contributions to the general good, nothing is asked of employers except that they continue doing what they would prefer to do. They are not asked to put their assets and know-how to direct public use. There is no requirement to produce all the personal protective equipment that would keep more people safe, especially those working in the health sphere. It is not demanded of them that they make facilities available for treatment, or put their technology to use to assist public health authorities to test, contact, and communicate. And, of course, drug manufacturers are not asked to share their precious vaccines with the billions of people who urgently need help. They are allowed to make superprofits. That is their birthright.

Any government that made “unwanted” demands of this kind on the owners of the means of production would be characterized as authoritarian, of using methods abhorrent to a liberal democratic society. The sovereignty of individuals and their private property is sacrosanct. The sovereignty of individuals without any property other than their capacity to labour, however, is not so respected. What the pandemic has shown is that the logic of capitalism dictates that the freedom of capitalists necessarily entails the subjugation of the working class. This consequence should be unsurprising. All the pandemic is doing is to make it more obvious to more people than usual. There is freedom from authoritarianism for some, but not for all.

Essential Workers in Non-Pandemic Times

The major feature which differentiates capitalist relations of production from other systems is its drive for accumulation of private wealth in a competitive setting, such wealth to be attained by extracting more value from the collectivized wealth produced by suppliers of labour who are paid less than the value of their output. As the Robert Fischl student exercise cited in the previous chapter demonstrates, there is no capitalism without the appropriation of value created by workers. In this sense all workers are essential to capital.

Mick Lynch, general secretary of the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers, puts it this way: “A wheel does not turn, a light does not go on without us. We create all of the wealth in this society, all of it. It is our labour which delivers the services, makes the goods, and distributes them to the people.”1

If this is true, why, then, do workers not do better, why are so many of them working on terms and conditions which do not allow them to do much more than scrape by? One reason for their obvious failure to do as well as they should is the role which law plays as it sets out to maintain and perpetuate capitalist relations of production, that is, the system which requires labour to be as costless as possible. This pushes law to enfeeble any potential bargaining powers that workers might have by dint of their centrality to the system.

Having placed the structural blocks for capitalism firmly into place, namely the right to own private property, which enables the owners to determine what they shall do with it, and having embedded the right of workers to sell their labour capacities, complemented by an ideological framework that makes it very hard to call these structural bases into question, law is in a position to instrumentally aid capitalists as they struggle with the working class. It does so. Often this is blatantly obvious. Contrast two real-life scenarios:

(a) A pharmaceutical firm has a monopoly over a needed drug. It decides that it will not supply it to those who need but cannot afford to pay for it. Those people’s health will be adversely affected. Occasionally a government might pay for the drug, in which case the pharmaceutical firm will deliver the drug. Often a government will confine itself to vexedly expressing its dismay and may try to cajole the pharmaceutical firm into relenting, to be kinder and gentler. The government will not use its legal power to coerce the pharmaceutical firm to do anything. The pharmaceutical firm is an owner of means of production. Law is not to be used to coerce it or any other members of its class.

(b) A union has a monopoly over garbage collection. It demands better wages and enforces its demand by striking the employer who refuses to pay any more. This affects public health adversely. If the strike continues for any length of time, a government is very likely to order the garbage collection workers to go back to work, more often than not on the same terms which they have lawfully rejected. An arbitrator will be appointed to determine the terms and conditions of a new contract with their employer. If they refuse to abide by the order to return to work, the union and individual workers may incur severe penalties. They are not owners of means of production. They are workers. Law feels free and justified to use its power to coerce them.

The difference in legal treatment is stark and revelatory. Property owners are not to be forced to do anything they do not want to do, even when their product or service is deemed to be essential. Workers whose supply of labour is essential in exactly the same way will be forced to labour, just as they were during the 14th-century Black Plague. And for this to happen, there is no need that there be an epidemic “forcing” the government’s hand. The lesson is clear: law will step in to prevent workers getting too much of an advantage over would-be employers. There are many instances of this instrumental legal privileging of capital over labour. In what follows, I comment on one: the way in which law approaches collective bargaining via trade unions.

As capitalism emerged, it was obvious to workers that the competition for jobs among them could only lead to hardship. One of their responses was to limit that competition, and they formed unions. Chapters two, three, and four describe the many battles that had to be fought by workers, physically, in the courts, and in legislatures. Those fights were necessitated because the owners of the means of production resisted these potential curbs on their search for profits. Both workers and capitalists have always been aware of the verity of the workers’ slogan: “United we bargain; divided we beg.” It took a long time, but, eventually, the legal right to form unions and to allow them to bargain on behalf of collectivized workers has gained some legitimacy.

The rights needed to make such collective bargaining truly effective vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. In none of them are they either full-blown or permanently guaranteed. For example, for the longest time, all Australian workers who belonged to the same occupational category were to be represented by one union which bargained on behalf of all such workers employed in an identified industry. Very soon after unions in North America got the legal standing they have today, they were limited to the representation of the employed by one employer. Such very different boundaries are themselves reflective of very different political struggles and, therefore, are always subject to change. Today, in Australia, unions’ bargaining rights have edged much closer to the North American model, while the North American model itself represents a winding back, first, of the early-20th-century movements to create one big union where bargaining was intended to be economic warfare between all workers and all employers and, then, of efforts by unions to be allowed to bargain on behalf of all workers employed in one industry (see chapter four for a longer discussion).

In all jurisdictions, there are likely to be workers in the private sectors who may not be represented by unions at all. Such a constraint is often imposed by law. When the constraint is imposed, it is because some workers are seen as vital to the employers’ ability to exercise their control over their property. Thus, anyone who might have some discretion over the deployment of the property (sometimes as lowly a person as a foreman), or who has access to confidential information about the employers’ books and plans, may be excluded from union coverage.

To form a union of approved workers, workers must clear a series of procedural hurdles before that union will be given legal standing to bargain on their behalf. For instance, they might have to prove that their chosen association is one that does not compete with an existing one or that its proposed bylaws fit with the scheme devised by law. Again, there are many variants which are left aside here; the point is that not all associations will be allowed to function as unions with full bargaining rights. Once a union has established itself as such, its negotiations may be given more bite because they will be able to threaten to withhold the supply of labour from employers. They will be allowed to call a strike. Again, while the processes vary across jurisdictions, strikes will not be legally supported until unions have satisfied a number of quite onerous requirements. For instance, they may have to conduct ballots to show support for a strike, something which leads to many challenges and costs; they will have to give notice ere they may strike, leading to a weakening of the threat; they may have to submit themselves to more negotiations, or conciliation or mediation procedures. Life isn’t meant to be easy for potentially militant workers.

The workers’ right to strike is not an embedded one. Rather it is a set of immunities (which some prefer to call a set of privileges) they have won, which protect them from repression by older laws which assumed that it was an abomination for workers to act collectively in a liberal capitalist democracy. The right of employers to strike – that is, to not invest their property or to de-invest it, the right to withhold private property – is actually a right, something that cannot be taken away by a legal instrument without justification. The field of battle created by supposedly neutral law is a tilted one. Even more so than described thus far.

If a government is persuaded that a strike conducted by a union which has met all the substantive and procedural requirements imposed by law is harmful to what it deems to be the public welfare, it will simply say “too bad” to the workers exercising their lawful rights. Sometimes governments give themselves the right to suspend the rights of workers explicitly; this was done by the Fair Work Act in 21st-century Australia. But this is not necessary. Governments have the residual power to suspend the operation of laws which they themselves have created and, when it comes to collective bargaining laws, they do so quite frequently.

The two scenarios posited above make it clear that when governments choose to ward off what they see as threats to public welfare, they are acting on the basis of having internalized the logic of capitalism. After all, they presumably could offset the adverse impacts of garbage collection (or transport or postal or rail or airline or school) strikes by ordering the employers to meet the demands of the workers in full. There is little doubt that this would restore the imperilled services. This is never done. The structural and ideological pillars of capitalist relations provided by law are so deeply embedded that, when governments force people to work on the basis of terms and conditions they had rejected – as the workers and their union believed they had a legally enforceable right to do – they are perceived to exercise their power to coerce legitimately. This general acquiescence of the propriety of legal intervention with legal rights should be puzzling, as it is manifest that it favours the employers’ position over that of their workers and their unions. Yet, if governments have to face any question at all, it is about whether it was really necessary to take away the workers’ right to strike as soon as it was done in this particular instance. The logic of this kind of challenge is not that governments should not exercise this kind of power, but that they should do so judiciously. After all, the purpose of a strike is to cause economic pain and discomfort, so why not let some pain be inflicted? It turns out that, in North America, there is a low threshold for this kind of pain.

In North America, the right to strike is a narrow one; it is limited to one workplace at a time. This diminishes the potential harm suffered by the public at large, although there are exceptions. Even the narrowly based right to strike may cause pain beyond the workplace setting. This is so when the employer is a municipality, or a producer of electricity, or a bus company. Such disputes present governments with a headache. They may be hurt politically if enough people think they got it wrong in any one case; they may be hurt politically if they do not intervene. Still, they do it often and it is fair to say that, in North America, the legitimacy of a government exercising this residual power against workers is rarely questioned, even if a particular use of it meets with disapproval. In the end, there is a tacit acknowledgement that workers are essential to the creation of welfare and may, therefore, be forced to work under conditions they do not voluntarily choose, whether or not there is the kind of pandemic which motivated the barons in 1351.

Sometimes, governments sweeten the pill when they deny individuals their right to assert themselves. In Canada, for instance, medical professionals, police officers, and firefighters are all considered essential and, therefore, are simply not given a right to strike, even if they are allowed to form associations that can negotiate on their behalf. Their power is too awesome to let them exercise it. Their services are just too essential. However, this also means that they are highly valued. Doctors, police officers, and firefighters are remunerated rather well. This is not the case for other workers who are integral to the services delivered by these respected professions: paramedics, personal-care workers, orderlies, cleaners, and, increasingly, nurses endure poor terms and conditions of employment. Like their well-remunerated counterparts in their chosen fields, they cannot help themselves by boosting their demands with a threat to withhold their necessary labour. They are viciously exploited. Many of them belong to racialized groups and/or are women.

The notion that, in a capitalist society, law permits people to control their own destiny, to deploy their talents and resources as they see fit, without any interventions by the State, always was, and remains, false. The privilege to be in control of one’s destiny belongs Essential workers 231 to the dominant class, and only to the dominant class. The idea is that the members of that class are essential and, therefore, must be given autonomy; workers are essential, both to the dominant class and to the public at large and, therefore, must have their liberty curbed. This is not the logic of liberalism; it is the logic of capitalism.

Here it is useful to note that, just as was the case in 1351, agricultural workers are seen as so essential that, in Canada, they had to fight for decades before it was acknowledged that they could associate with each other to advance their bargaining goals, but, as yet, their associations have not been accorded a right to strike. Unlike doctors, police, or firefighters, they are poorly paid. They are even worse off if they fall under the category of migrant workers.

And there are other like circumstances in which the potential leverage that a right to strike bestows is inhibited by legal fiat. This happens most obviously when the workers are government employees.

Another Legal Manoeuvre: Splitting the Economic From the Political

Conceptually, an argument is plausible that government employees should be treated differently. Political struggles have led to legal reconstruction of the market for labour by overcoming, to different extents in different circumstances and jurisdictions, the weakness of individual workers when they have to offer their labour power to employers. The notion is that when workers are permitted to withhold their labour collectively, they will be able to convince employers that they will lose more by not satisfying workers’ demands than by giving in to them. Collective bargaining is, first and foremost, an economic instrument: it alters the economic calculations of the adversaries. This limits the demands that can be made by workers on employers to being demands for economic gains or for better conditions to be applied in the workplace setting. Collective striking power, being a market-restructuring institution, cannot be used, legally speaking, for any other purpose. This restriction raises a question: Does this narrow economic role make sense in the government sectors?

Governments are not trying to maximize profits. They have no structural reason to extract surplus value from their labour force. They are in the “business” of providing services that they have politically determined should be delivered to the public or special segments of it. When workers make demands that a government does not want to satisfy, the nature of the struggle is different to what it is in the private sectors. Governments find it easy to contend that a group of self-interested workers are making claims which, if agreed to by the governments, will force them to make changes in the quantity and quality of services they are providing. Governments will be forced to make changes to their politically made decisions on how much service or welfare to provide to the public or to specific sectors. In short, they are able to say that a mechanism devised to redress economic power imbalances in the for-profit spheres is being used to change legitimated democratic political decision-making.

This line of argument makes it easy for governments to limit bargaining and strike rights in the public sectors if they are minded to do so. In a letter by President Roosevelt (the man praised for pushing through bargaining and strike rights of workers as part of the New Deal) to the president of a federation of public employees, Roosevelt said that the process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, “cannot be transplanted into the public service … administrative officials and employees alike are governed and guided, and in many cases restricted, by laws which establish policies, procedures or rules on personnel matters.” He went on: “Particularly, I want to emphasize my conviction that militant tactics have no place in the functions of any organization of Government employees.”2

In North America, governments are very inclined to curb any powers public sector employees might gain by having relatively legally unfettered bargaining and strike rights. In the US only eleven states have eliminated bans which existed on public employees’ stoppages. In the wake of large-scale teachers’ strikes in 2018/19, all of them unlawful, there have been legislative attempts to give public employees more bargaining powers that might allow legal strikes to take place. The fact that governments which adamantly claim they defend the right of all their citizens to assemble, to associate, and to speak freely have, thus far, felt it rather easy to justify their constraints on these fundamental rights when it comes to public sector workers speaks volumes to the power of the argument which allows a liberal capitalist economy to draw a sharp line between the economic and political spheres. Here I remind readers that President Reagan relied on this divide to dismiss all the air traffic controllers when they sought to use their collectivized power to get better conditions. In the end, his argument rested on the claim that, as the embodiment of a political institution, he was acting on behalf of the public good, while the air traffic controllers were just trying to satisfy their narrow self-interest and using their economic heft to do so.

In Canada, provincial and federal laws sometimes forbid government employees from bargaining about some issues, those issues said to be too important to be left to anyone but an elected government; sometimes, public sector workers are given very similar bargaining and strike rights to those which obtain in the private sector, but some workers may be designated as essential workers. They will not be allowed to participate in any strike, effectively being required to act as scab labour should their comrades take action against their common employer. More importantly, there has been a much-noted increase in the frequency with which governments use their political power to order workers back to work should they engage in lawful strikes, forcing them to submit to an arbitrated set of conditions and terms.

The pandemic drew the public’s attention to how essential workers’ contributions are to the creation of wealth. It turns out that law creates conditions which make it as hard as possible for workers to use the bargaining strength this should give them.

Summation

1. This brief overview should suffice to make the point that there is a wide acknowledgement that without the work-for-wages relationship, a capitalist economy cannot exist. In a capitalist economy, it is assumed that owners of capital are crucial, always essential, no matter what they do with their capital. It is assumed that owners of the means of production must not be told how to use them.

2. The drive to search for profits means that capitalists’ use of their assets must be interrupted as little as possible. During the pandemic, this requirement forced governments to balance what they called “the economy” against public health measures. Many workers were declared essential and forced to work, whether the output of their work was actually needed or merely desired. Their freedom to sell their labour power was turned into a legally enforced duty to do so. This drew attention to the fact that many lowly regarded and vulnerable working class people contribute to profitable undertakings but are not rewarded accordingly.

3. In turn, these measures brought out the fact that, in non-pandemic times, the self-same workers do work that is essential to capitalists. Governments have internalized the unchallengeable nature of private property rights and the emphasis on individualism and go out of their way to ensure that capitalists will not be robbed of essential workers as defined by capitalist needs.

4. Workers are exploitable because of their numbers, and they seek to reduce competition among themselves. Capitalists do everything within their power to blunt collective working class responses. Capitalists faced with collectivized workers can count on governments to limit the powers of workers who have won some collective bargaining and strike rights.

5. Governments treat their own employees as essential employees on the basis that the governments are delivering essential services. For such democratically mandated services to be interrupted by striking workers is an unwarranted use of economic power to defeat the legitimate exercise of political power.

6. To maintain capitalist relations of production, it is necessary to treat members of the working class as inferior members of the polity. This logic will not change until the structural and ideological foundations provided by law are confronted. Merely to change the instrumental laws which momentarily regulate the settlement of capital-labour disputes will not allow workers to become equals, even if they win some relief from some of the harsher outcomes which they currently endure. •

Watch video of book launch. For full expository notes to each chapter, or to purchase the book, please visit btlbooks.com/book/law-at-work.

Endnotes

- The quoted passage by Mick Lynch comes from a speech he gave at a rally at King’s Cross Station in London on June 25, 2022. It can be found at @RMTunion. The rally was part of a campaign preparing workers for a possible strike. It attracted attention because it was publicized under the heading “We Refuse to Be Poor.”

- The quotation from Roosevelt is from “Letter to Mr. Luther Seward, President of the National Federation of Federal Employees, Aug. 16, 1937.” Roosevelt’s ideas were embedded in the Taft-Hartley Act, Labour-Management Relations Act, 29 U.S.C.A. P.L.101—80th Cong. Sect. 305. For a comment on recent attempts to ban similar legislation banning public employees to bargain and/or strike, see Matt Murphy, “Public Employees Press Right-To-Strike Legislation,” State House News Service, July 14, 2021.