Neoliberalism is Canada’s Real Productivity Problem

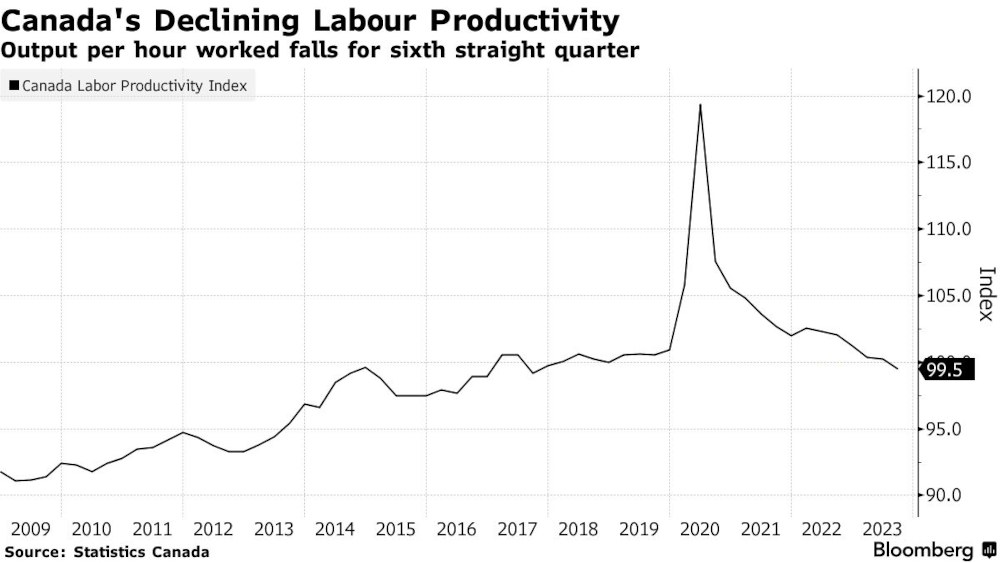

It is rare for the Bank of Canada to say that we face a national economic emergency. But that is exactly what Deputy Governor Carolyn Rogers did on March 26. She was referring to Canada’s dismal record on labour productivity, which is indeed a major, albeit long-standing issue. Her widely publicized speech put a sharper focus on very weak Canadian economic performance, especially relative to the United States.

As Rogers said, “labour productivity measures how much an economy produces per hour of work. Increasing productivity means finding ways for people to create more value during the time they’re at work. This is a goal to aim for, not something to fear.”

The labour movement has long understood that raising output per hour of work through more investment in machinery and equipment (as opposed to work intensification) lays the basis for negotiating rising wages and living standards and investing in social programs and public services. Higher productivity can also support the reduction of working time.

Productivity on the Decline

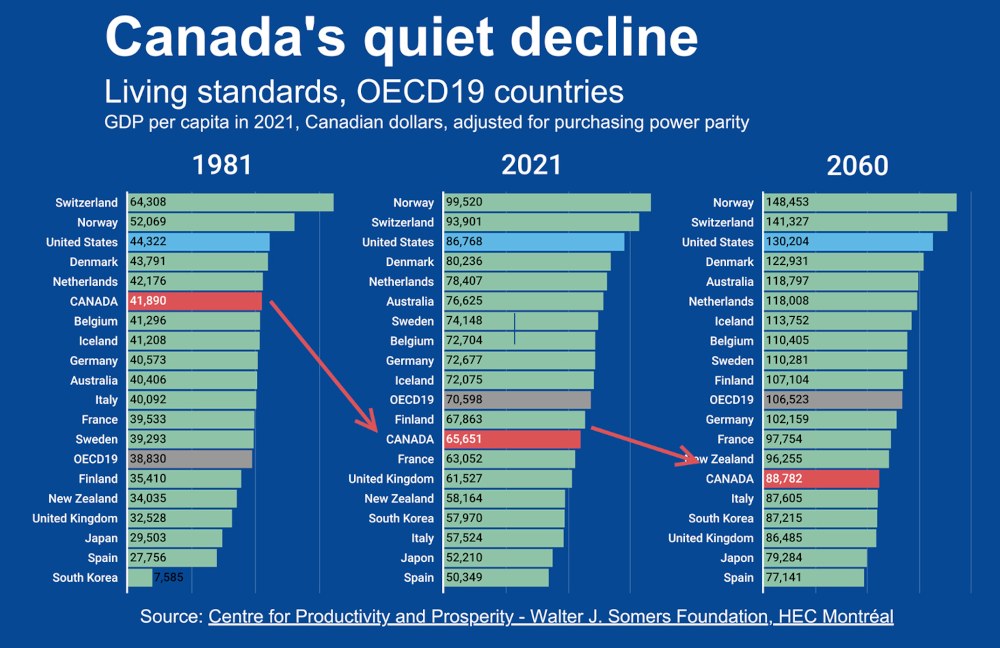

We can all agree that Canada’s productivity record is appalling. According to Rogers, output per hour is now just 70 percent of the US level, down from almost 90 percent in the early 1980s. Over the long run, our performance has been the worst of any major industrial country save Italy.

Economists across the political spectrum agree that the main sources of long term productivity growth are investments in machinery and equipment, new technologies embodied in new products and services, intellectual property and education, and skills. High productivity, high wage economies are on the cutting edge of innovation.

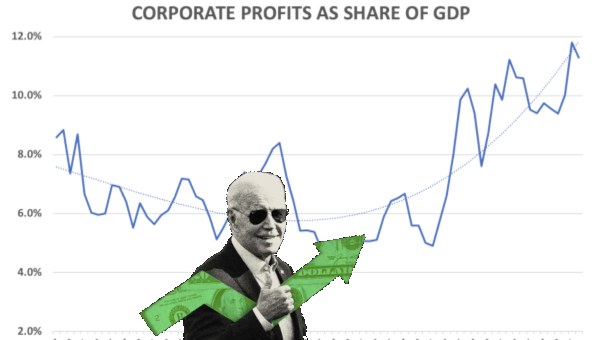

Mainstream neoliberal economists and policymakers generally argue that governments should mainly set the stage, or create favourable conditions, for the business sector to invest. This is done through so-called market friendly framework policies such as low inflation, liberalized trade, deregulation and privatization, and low taxes on capital.

Rogers calls for fostering more competition and encouraging businesses to invest more. Mainstream economists and policymakers generally give the priority to private investment and lower taxes, rather than public investment, even though the latter can make a powerful contribution to productivity growth.

Public investment in areas like infrastructure and education are clearly basic building blocks of a successful economy, complementing business investment. Going one step further, public investment in skills and research and development as well as all kinds of subsidies and even public enterprises like Crown corporations have partially made up for the chronic deficiencies of the Canadian private sector.

A central problem with the mainstream approach is that it has been tried and has manifestly failed. A recent Globe and Mail column by Andrew Coyne was headlined “How could we do so poorly? We did everything right!” Legions of economists have lamented the failure of neoclassical economic policies to deliver.

Coyne further notes that this failure also largely applies to modestly interventionist and costly government policies such as subsidies to business investment. These fall well short of public sector leadership and genuine investment planning, which has fallen into disfavor in the neoliberal era (though “Bidenomics” may mark a modestly successful shift in direction).

Key Structural Problem

Rogers is silent on the key structural problem, specifically the nature of Canada as an export and foreign investment driven resource-based economy with only a relatively small, sophisticated industrial sector.

Canadian political economists from Harold Innis to Mel Watkins have long identified the staples underdevelopment trap and the need to deepen the domestic economy through managed trade and hands on industrial policies. These were pursued in the 1970s but were largely undercut by the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement from 1988.

It is deeply ironic that “free trade” was sold as the cure to Canada’s productivity problem, and is widely held to be a great success by the same policymakers who lament our poor productivity record. Instead, neoliberal policies resulted in deindustrialization outside the booming energy sector.

Rogers also fails to acknowledge that the neoliberal economic framework may actually exacerbate the productivity problem. Targeting low inflation even more stringently than the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of Canada has often, as today, undermined business investment through excessively tight monetary policy.

In the US, governments have more often let the economy “run hot.” Low unemployment results in higher wages which pressure companies to invest in new capital equipment and skills, raising productivity.

In Canada, the unemployment rate has been generally higher than in the US, and temporary workers have been used to contain wage growth. Yet no one at the Bank of Canada is calling for higher wage growth to boost productivity.

The left should not discount the importance of raising productivity. But more of the same economic policies is not the answer. •