Wealth and the Invisibility of Human Life

Quinn Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Quinn Slobodian’s masterful exegesis, an old term befitting his subject, tells of the Ur group of thinkers who formulated the assumptions and prescriptions of global neoliberalism. He names this group the Geneva School as distinct from the Chicago School. He suggests that their early attentiveness to the global level came from Central Europe’s dependence on foreign trade and external markets unlike the United States at that time. The original source material suggests that they were motivated by considerable anxiety following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. For them the empire was a supranational order of efficient and stable security. They saw chaos coming from demands for redistribution, preferential treatment, and self-determination by the ‘masses’.

In his introduction, Slobodian corrects erroneous assumptions about neoliberal theory: they didn’t believe in self-regulating markets as autonomous entities; they did not see democracy and capitalism as synonymous and they did not see people as motivated only by economic rationality. The Geneva School sought to safeguard capitalism at the scale of the entire globe, to protect competition and capital against the threat of irrational human behavior. Neoliberalism arose after World War I at a time of crumbling empires when a number of intellectuals grappled with how to balance state power and economic interdependence.

In his introduction, Slobodian corrects erroneous assumptions about neoliberal theory: they didn’t believe in self-regulating markets as autonomous entities; they did not see democracy and capitalism as synonymous and they did not see people as motivated only by economic rationality. The Geneva School sought to safeguard capitalism at the scale of the entire globe, to protect competition and capital against the threat of irrational human behavior. Neoliberalism arose after World War I at a time of crumbling empires when a number of intellectuals grappled with how to balance state power and economic interdependence.

The Geneva School solution was “double government”: global jurisdiction for capital, with the nation state “encasing” capital from encroachment by particular interests. The League of Nations, founded after World War I and located in Geneva, had set about to reorder European states and their former imperial possessions.

They believed that the one determinant of global stability was the unimpeded flow of capital and that politics and economics needed to be distinct. For example, most Geneva School neoliberals opposed South African apartheid, and Friedrich Hayek was unambiguous in his public denunciation of apartheid, yet he had “even stronger words for attempts by international organizations to use sanctions and embargoes against South Africa.” Fascism looked promising to some until it raised tariff walls. Hayek was opposed to criticizing Chile under Augusto Pinochet.

20th Century: Three Ruptures

They saw three ruptures to the world economy in the 20th century, each accompanied by “the democratization of the world”: World War I when nations ceased to uphold the gold standard and blurred the distinction between the economy and politics; the 1929 Great Depression; and the revolt of the Global South starting in the 1970s with the declaration of a New International Economic Order (NIEO). In principle, the Geneva School opposed state autonomy. They saw the European Economic Community as a potential model for a “world of constitutions” while they opposed its protective measures and its “most favored” trade arrangements with former African colonies. Their core value is not freedom of the individual but the interdependence of the whole.

The Depression and suspension of the gold standard generated efforts by economists to research the global economy and stave off future crises. They focused on statistical data and measurement, aiming to control the business cycle and to permanently prevent economic collapse. The Geneva neoliberals, especially Hayek, concluded that the economy was unknowable and they redirected their attention to cultural and social bonds, tradition and the rule of law which in itself was disintegrating in the 1930s. Hayek saw the world economy as “sublime” – beyond human comprehension. Stability was to come through order, “ordo”, at the national and global levels, through laws and institutions.

The 1938 Walter Lippmann Colloquium in Paris sought to create a new liberalism that would protect trade and capital movement between nations. They differed with Keynes who lauded national self-sufficiency. Anticipating the conceptual separation of civil/political from social/economic rights in the UN Charter, the Geneva School posed the rights of capital and investors against the rights of people: the right to move capital freely over borders, and protection from expropriation and capital control. Philip Cortney, an extremist neoliberal at that time, went so far as to liken human rights to appeasing Hitler and exchange control as an act of aggression; his lasting contribution was to frame economic rights in the language of human rights.

Universalists vs Constitutionalists

Slobodian reviews in detail the involvement of the Geneva School with three institutions: the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the European Economic Community (EEC) established by the 1957 Treaty of Rome, and the 1995 World Trade Organization. From the 1944 Bretton Woods meeting came the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank but not an institution for overseeing world trade.

The globalists were split between universalists and constitutionalists. The universalists opposed all protectionist, preferential interests while others more pragmatically saw the EEC as a model of a future global constitution-based arrangement. They called for formal equality among states and saw danger in pluralistic demands that could easily threaten the system as a whole. The constitutionalists saw that at times the state needed to absorb challenges and reach settlements, such as by providing welfare or labour benefits. Gottfried Haberler, a universalist, wanted to strengthen GATT as a ‘watchdog’ against Europe; “Europe may profit [through the EEC] ‘but the world economy as a whole loses’” (p 203). The Geneva School defined orders as a “perpetually shifting relationship” for guiding price signals. The concept of supranational mechanisms to protect capital emerges in tax havens and banking secrecy, Investor State Dispute Settlement arbitration, fiduciary obligations to grow capital in corporations and pension funds, buying up sovereign debt.

Corporations as Persons and Invisible Individuals

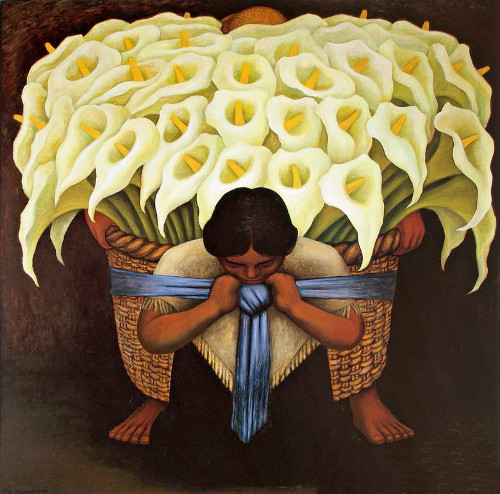

Slobodian’s concluding chapter is titled “A World of People without a People.” To this reader, the neoliberal theorists resemble Arendt’s Eichmann in their dehumanizing of humans and seeming obliviousness to the human condition. Slobodian describes two book covers. Ernst-Ulrich Petersmann, following Cortney, was a vocal proponent of using the language of human rights to build a world economic order. Petersmann’s book cover is ironically from communist artist Diego Rivera’s Calla Lilly Vendor (1941): a woman bowed under the weight of a mountain of beautiful white flowers. Petersmann, blind to human suffering, called it an icon of the “freedom to sell in the market place.” Slobodian pointed out that across the street from the Centre William Rappard in Geneva, which first housed the International Labour Organization and then the GATT, Petersmann would have to have seen the monument to work: “miners picking at a coalface, fishers at sea, farmers tilling and hauling crops, … a hooded indigenous man carrying pelts, a man in a worker’s apron holding pincers, and a black African man with a hoe.” Engraved in the plinth: “Labor exists above all struggle for competition. It is not a commodity.” The second book cover is from former WTO director Pascal Lamy’s book: barely perceptible beneath a grid of crosses and flecks of color is a Mercator projection of the world – absent are people.

There is much to think about here in our world of intellectual confusion in which words obscure the relationship of people with each other. Slobodian’s original source material helps to disentangle one significant reversal: the hand of the market is not an invisible sublime process; often the hand belongs to Eichmann-like people for whom people in general are invisible. This double invisibility links neoliberalism with liberalism in its pre-Marxist and pre-Freudian assumptions about individuals and society, resulting in gross reductionism. There is Marx’ concept of reification and Freud’s concept of condensing ideas with things: capital is treated as an irreducible thing in itself. This obviously leads to the disastrous commodification (monetization) of human life and of the basic necessities of life – the so-called ecosystem services. How can military spending for killing use the same unit of measurement as spending for goods and services that are to protect priceless life? Arendt’s insight into Eichmann and his society is that this kind of immorality is banal and is not seen for what it is. Neoliberalism mystifies and idealizes: ‘there is no alternative’, ‘too big to fail’. Behaviorism and neuro-reductionism are the complementary psychologies.

Marxist historian Ellen Meiksins Wood writes of England’s “pristine” capitalism, not palpable and material, and describes how even the richness of the English language became sterile during the 18th century English enlightenment. In Shakespeare’s great play on justice, the Merchant of Venice cannot see ordinary human materiality as represented in the figure of Shylock; the merchant’s character and his legalistic compatriots live in a constricted world of capital and are shorn of feelings, desires, and inner conflict. Shylock demands a pound of flesh from the merchant as payment of debt: bodily pain in exchange for the emotional pain of being disrespected and robbed of his personhood.

At the same time that the Geneva School first worked together, Robert Musil was writing the novel The Man Without Qualities. We learn in the first few pages that the man is a scholar who thinks only in quantities, who walks past an accident victim and only thinks of accident statistics, who calculates human energy output, but who has unpredicted bursts of physical aggressiveness. Quite a contrast to James Joyce’s Ulysses whose ‘everyman’, Irish-Jewish Leopold Bloom, knows his own inner feelings and bodily sensations and who is able to love people.

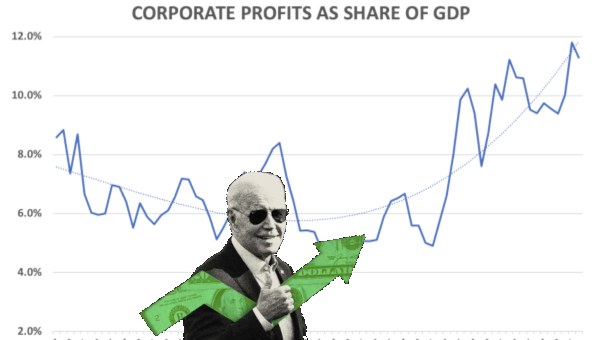

Human invisibility is intrinsic to the current frightening and pathogenic belief system. As a case in point, in a recent lawsuit against gender discrimination, Walmart female employees were not legally recognized as a class and could not file a class action lawsuit, while the Walmart corporation was legally recognized as a person. Autonomous institutions that are unanswerable to the people demand urgent attention. The omnipresent supranational political/economic order, backed by the military and law, threatens human extinction from climate change and nuclear war, and the people in charge are impervious. It is virtually hidden in plain sight. •