Global Trade in Renewable Energy Assets Soars

Secondary market transactions are a common feature of Public Private Partnerships (Whitfield, 2010, 2016, 2017, 2019) and are now a core element of the renewable energy sector as detailed in Challenging the Rise of Corporate Power in Renewable Energy. A secondary market transaction includes the sale/acquisition of renewable energy assets at different stages ranging from the sale of rights, with or without a Power Purchase Agreement, to those in construction or operational projects.

A Global Renewable Energy Secondary Market Database was developed with a total of 1,622 renewable energy transactions in a three-year period from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2021. The annual number of transactions increased from 398 in 2019, 537 in 2020, to 687 in 2021, an increase of 72.6% in the period. Transactions continued at a similar rate in 2022 and 2023.

The database includes transactions with share purchase agreements to acquire equity in renewable energy companies. The formation of partnerships or joint venture companies may ultimately affect the ownership of assets, particularly if one company later wants to sell their stake.

Each transaction in the database identifies the vendor, purchaser, a brief description of the transaction, the type of renewable energy asset (onshore or offshore wind, solar, hydro, energy from waste, biomass, battery/storage, district heating, or grid); the total Megawatt (MW) or Megawatt peak (MWp) of the project; the percentage of equity ownership, country location, sale price (where disclosed), and the prime data source.

| Table 1: Annual rate of secondary market transactions 2019-2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of transactions | ||||

| Renewable energy asset | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Total |

| Wind | 170 | 177 | 199 | 546 |

| Solar | 144 | 238 | 310 | 692 |

| Combined wind & solar | 30 | 42 | 53 | 125 |

| Hydro | 11 | 18 | 18 | 47 |

| Battery/storage | 9 | 14 | 37 | 60 |

| Energy from waste | 3 | 6 | 5 | 14 |

| Other | 31 | 42 | 65 | 138 |

| *** Annual Total *** | 398 | 537 | 687 | 1,622 |

| MW/MWp | ||||

| MW/MWp (based on 1,455 transactions) | 109,816 | 245,766 | 424,946 | 780.528 |

| Total MW/MWp assuming 100% data | 870,154 | |||

| Expenditure US$ millions | ||||

| Expenditure based on 504 transactions | 44,485 | 68,598 | 93,640 | 206,723 |

| Expenditure assuming 100% data | 671,783 | |||

| Source: ESSU Global Renewable Energy Secondary Market Transactions Database, 2019-2021. Excludes new transmission contracts but includes 4 secondary market transactions of the sale of equity stakes in grid companies. |

||||

Impact of the Secondary Market

The secondary market increases the role of markets and market forces in renewable energy and consolidates market interests. The market creates new opportunities for profiteering from the generation of renewable energy. Revenue from the sale of assets accrues to the parent company that owns the equity and does not directly benefit the project, community, or local economy.

Changes in the ownership of assets may alter the priority of certain projects, but it does not increase investment in existing assets except when older assets are acquired for upgrading or repowering.

Changing corporate ownership via private negotiation may lead to the weakening of the original environmental and community commitments by the new owners.

Increased use of tax havens results when companies and investment funds seek to minimise or avoid tax liabilities in order to maximise profits.

There is a fundamental lack of democratic accountability because the secondary market operates independently of governments and international agencies (except when regulatory approval is required for a transaction).

The financial resources of Private Equity Funds give them a significant advantage. For example, Brookfield Renewable Partners is active in the renewable energy secondary market, having acquired 19 assets and sold 6 in the three-year research period.

“In 2019, we also continued to execute our capital recycling strategy of selling mature, de-risked or non-core assets to lower cost of capital buyers and redeploying the proceeds into higher yielding opportunities. During the year, we raised almost $600-million ($365-million net to BEP) through this funding strategy, allowing us to crystallize an approximate 18% return on our Portuguese and Northern Ireland wind assets and to return more than two times our capital invested in South Africa” (Brookfield Renewable Partners, 2020).

In 2022 Brookfield announced that it was considering spinning of its asset management business reportedly valued at over US$75-billion.

“The manoeuvre would simplify the structure of the sprawling Toronto-based company, separating the division that manages $364-billion in fee-bearing assets across real estate, infrastructure, renewable energy, credit, and private equity on behalf of institutional investors from Brookfield’s $50-billion of directly-owned net assets.

“‘The financial markets have evolved. What people like are asset-light models,’ Bruce Flatt, chief executive of Brookfield, told the Financial Times. ‘It appears that there is an enormous amount of shareholder value to be unlocked’” (Financial Times, 2022c).

Shareholders Scoop Multi-Million Dividend Payments

The payment of annual dividends to company shareholders is an indicator of the company’s annual profits. Dividends are paid in cash (or the option of additional shares) and are designed to incentivise continued holding of the shares. Privately owned renewable energy companies and the subsidiaries of larger companies (which only pay dividends for the company as a whole) were excluded from the sample.

Annual dividend payments to shareholders in a sample of 20 private renewable energy companies totalled a staggering US$10.7-billion between 2019-2021. The companies were selected from the ESSU Global Renewable Energy Database 2019-2021 as public companies that issue shares to raise capital in order to fund renewable energy projects and are listed on a stock exchange. They include the privatised National Group Plc. (1996) which operates the UK Grid as well as the New York and Massachusetts grid, developing and operating renewable energy projects in several US states.

Dominant Role of Private Equity Funds

Private equity funds acquired 369 renewable energy assets in the 2019-2021 period and sold 178 assets, a total of 547 transactions or 33.5% of the total transactions in three years. It is significant that private equity funds had a net gain of 191 acquisitions. The large global firms – BlackRock, Blackstone, Brookfield, Carlyle, Goldman Sachs, and KKR – reflected this pattern by acquiring 47 assets and selling 20. Similarly, infrastructure funds such as Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, DIF Capital Partners, Foresight Group, Partners Group, and SUSI acquired 51 assets and sold 21.

“The amount of money invested, or waiting to be invested, by private equity funds has swelled from $1.3-trillion in 2009 to $4.6-trillion today. This was driven by a scramble for yield among pension funds, insurance companies, and endowments during a decade of historically low interest rates in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2007-09. Many have more than doubled their allocations to private equity. Since 2015, the ten largest American public-sector pension funds have collectively committed in excess of $100-billion to buy-out funds” (The Economist, 2022b).

Brookfield Renewable Partners LP (registered in Bermuda) has 45,900MW operational assets and development pipeline in the USA; 20,800MW in Europe, 12,800MW in South America and 10,400MW in Asia Pacific. It operates hydroelectric, wind, solar and storage facilities in North America, South America, Europe and Asia. It acquired Scout Clean Energy with 2,500MW renewable energy assets for US$1.35-billion and Standard Solar for US$700-million with 500MW operational assets and a 2,000MW development pipeline in 2022.

Tax Avoidance is Widespread in Renewable Energy Companies

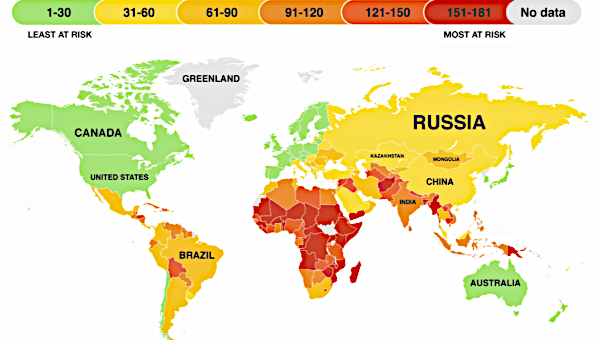

The use of tax havens to shift profits to low tax countries as a means of avoiding or reducing taxation is common in renewable energy companies. It not only means a loss of tax revenue for countries with renewable energy projects but also increases corporate secrecy and reduces democratic accountability.

The ESSU Global Renewable Energy Secondary Market Database identifies 43 companies registered in tax havens engaged in 264 transactions that acquired renewable energy assets and 47 that sold assets. The 310 transactions account for 19.1% of the database transactions. This is likely to be an under-estimate because it has not been possible to undertake a detailed analysis of every transaction and company corporate structure.

The tax havens most frequently used by renewable energy companies disclosed in the ESSU database are Luxembourg, Jersey, Guernsey, Bermuda, and the Cayman Islands, which rank 6th, 8th, 17th, 2nd and 3rd respectively in the Tax Justice Network’s Corporate Tax Haven Index 2021.

Multiple Use of Tax Havens

Some companies operate by being registered in more than one tax haven. For example, National Grid plc operates in England and Wales and Eastern states in the USA and has subsidiaries registered in Netherlands, Luxembourg, Hong Kong, Jersey, Republic of Ireland, and Isle of Man, which are ranked 4th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 11th, and 20th in the Tax Justice Network Corporate Tax Haven Index 2021.

Scale of Public Ownership

Governments and public authorities are involved in renewable-energy policy making, auctions of project sites, approving planning permission, subsidies, and guarantees intended to attract private investment in renewable energy. The World Bank, the International Finance Corporation, regional development banks, and overseas aid agencies provide direct finance or loans to similarly attract private investment in the global south. This investment model is a repeat of the corporate welfare role that became common in other sectors over the last 40 years. The roots of the renewable energy market lie in the privatisation of utility and fossil-fuel companies in many countries over the last forty years, culminating, for example, in the UK, with the sale of the UK’s Green Investment Bank to Macquarie Group in 2017.

The degree of state ownership varies enormously. Statkraft (Norway), Vattenfall (Sweden), China Three Gorges Corporation, and Masdar (UAE) are 100% state-owned companies. In addition, there are six companies in which the state has between 96.10% and 50.10% ownership, followed by those with a minority stake. Currently the French and Italian governments have minority stakes of 23.64% and 23.58% in Engie and ENEL respectively. Institutional shareholders own 86% of RWE (26% based in Germany). China Three Gorges owns 21.55% of EDP (Portugal) with BlackRock private equity holding 5% as well as holding similar stakes of 7.13%, 7%, 5.16%, and 3.51% of SSE, RWE, EDP, and Engie respectively (2019/2020 data). The Qatar Investment Authority owns 8.69% and 2.27% of Iberdrola and EDP respectively.

The total global installed renewable-energy capacity in 2021 was 2,838.8GW. Wind accounted for (743GW), solar (760GW), hydropower (1,170GW), bio-power (145GW), geothermal (14.1GW), concentrating solar thermal power (6.2GW), and ocean power (0.5GW) (REN21, Global Status Report, 2021).

| Table 10: Global public sector renewable energy assets | ||

|---|---|---|

| Company | Projects | MW |

| Statkraft (Norway) | 412 | 17,815 |

| Vattenfall (Sweden) | 121 | 16,878 |

| China Three Gorges Corp. | 32 | 1,431 |

| CGN Energy (China) | 47 | 2,039 |

| CGN Europe | 23 | 2,653 |

| CGN Brazil | 8 | 1,182 |

| Masdar, Mubadala Investment Co. (UAE) | 33 | 2,681 |

| EnBW Energie Baden Wurttemberg AG | 134 | 4,400 |

| Electricity Suppl Board (Republic of Ireland) | 4 | 639 |

| EDF (France) | 386 | 16,889 |

| Hidroelectrica (Romanian) | 187 | 6,422 |

| CEZ group (Czech Republic) | 73 | 3,124 |

| Equinor ASA (Norway) | 7 | 553 |

| Orsted (Denmark) | 21 | 13,000 |

| Partial public ownership | ||

| ENI (Italy – 30.33 public) | 23 | 345 |

| Engie (France – 23.64% public) | 160 | 8,463 |

| ENEL (Italy – 23.6% public) | n/a | 11,814 |

| *** Total *** | 1,671 | 98,514 |

| Sources: Company Annual Reports and websites 2021. Excludes projects at development stage. | ||

Publicly-Owned Companies Buy and Sell Renewable Energy Assets

The twelve major publicly owned renewable energy organisations/companies, plus three major companies that have a minority public shareholding, own 1,671 projects with 98,514MW operational capacity or 3.47% of the global total. Public sector acquisitions increased their share by 37,927MW, but the sale of assets to the private sector led to a reduction of 24,660MW.

The net public sector impact was a gain of 13,267MW or +0.46%; thus, the public sector owned 4% of global renewable energy MW in December 2021.

| Table 11: Public sector acquisition and sale of renewable energy assets 2019 – 2021 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of public sector transactions |

Total MW in transactions | % Impact GW | |

| Acquisitions by public authorities | 79 | +37,927 | 1.33 |

| Sale of assets by public authorities | 41 | -24,660 | -0.87 |

| Sale of assets between public authorities | 20 | 9,273 | 0.0 |

| Net impact | +38 | +13,267 | +0.46 |

| Source: ESSU Global Renewable Energy Secondary Market Database, 2022. MW not provided in 18 transactions. |

|||

Transactions Continue in 2023

Private Equity Funds and Asset Management Companies continued deals with Spanish utility Naturgy Energy Group, acquiring a 422MW portfolio of wind farms and a pipeline of 435MW of solar parks in a US$709-million deal with Ardian Infrastructure Fund. Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners launched a new onshore renewable developer, Baldur Power in Hamburg, to focus on solar, wind, and battery storage projects.

Actis Private Equity launched Nozomi Energy a new renewable energy company in Japan with US$500-million resources and immediately acquired 100% ownership of Hergo Japan Energy Corporation from Infrastructure S.p.A. A joint venture between Actis and Mainstream Renewable Power sold Lekela Power, Africa’s largest renewable company, with over 1GW of wind assets, to Infinity Power, a joint venture between Egypt’s Infinity and UAE’s Masdar.

Brookfield Renewables and EIG Consortium acquired Origin Energy in Australia in a $18.7-billion deal that includes creating an integrated global LNG portfolio with Brookfield building 14 GW of new renewable generation and storage facilities.

Challenging Corporate Domination of Renewable Energy and Rationale for Wider Public Ownership

It is vital that corporate domination of renewable energy is challenged, combined with establishing the case for increased public investment and ownership of renewable energy.

Challenge and replace the obsession with ESG:

Use the weaknesses in Environment, Social, and Governance to challenge the performance of private renewable energy companies. ESG should be replaced with a commitment to undertaking rigorous and comprehensive equality impact assessments. This should be modelled on the best practice Section 75 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 (Equality Commission for Northern Island, 2010). All renewable energy projects should be subjected to comprehensive and rigorous economic, equality, social and environmental impact assessments and cost/benefit analyses and include how human and labour rights will be advanced and evidenced.

Challenge the use of tax havens and demand this practice be terminated:

Tax avoidance increases corporate profits and shareholder dividends but has little or no benefit for service users or employees. The use of tax havens reduces tax revenue in the host country, which is likely to have a small impact in the case of a small renewable energy asset but represents a larger revenue loss when all the projects in a country using this avoidance strategy are taken into account. Tax avoidance means corporate financial secrecy and less local democratic accountability concerning profitability and the ability to challenge claims by companies with regard to employment conditions, activity in the local economy, and supply chains.

Challenge the policy, justification, and process if a company seeks to sell a renewable energy asset:

Identify a set of demands that should be included in a sale agreement, drawing on the degree to which the original commitments have been met, along with new demands arising from the operation and management of the project. If it is financially driven asset recycling, then who are the potential buyers and are they likely re-sell again soon? In addition, new regulations should be considered such as, any sale should require the repayment of subsidies and the protection of terms and condition for staff upon transfer to a new owner.

Challenge the lack of democratic accountability and participation:

Democratic accountability is critical at national, regional, and city levels for energy policies, long-term planning, repowering, and upgrading. Firstly, it must include genuine and continuous participation of community and trade union representatives in the planning and service-delivery process. Secondly, it must evidence full monitoring and reporting of the implementation and performance of public-sector values. Thirdly, a regular scrutiny/oversight review and evaluation by public authorities should include evidence and evaluation from contractors/suppliers and from community organisations, trade unions, and other interested organisations. Finally, the scope of the above should include the effectiveness of regulations, progress in the transition from fossil fuels, and stranding of assets and economic development initiatives linked to renewable energy projects.

Challenge failure of local economic development in construction and operation of assets:

Identify whether local companies were employed in the construction process and the tasks they were responsible for. Similarly, determine if any operational activities have been outsourced in the planning, construction, and operation of wind, solar, hydro, or battery storage projects and gather information about any disputes over terms and conditions and trade union recognition.

Challenge level and quality of local employment generated by the project:

Gather information about the terms and conditions of workers employed by the company and in work that has been outsourced. Compare with the terms and conditions of comparable workers/skills in other sectors.

Challenge Private Equity Funds:

The Americans for Financial Reform and Private Equity Stakeholder Project has developed the Private Equity Climate Risks Scorecard, which has graded eight private equity funds with a combined US$3.6-trillion in assets under management.

Demand that fossil fuel companies do not make ISDS or Energy Charter Treaty claims against nation states:

Nor should they take other forms of legal action over changes in climate policies that are in the public interest.

Rationale for New Public Sector Organisations

Local authorities should establish or expand existing organisations to undertake retrofitting of housing and public buildings as well as developing environmental protection projects, such as flood prevention work, sea wall, and river basin works. These authorities should also provide a continuing maintenance, repair, and improvement/upgrade service. Arms-length companies or privatised direct-works departments should be returned to direct public provision.

Retrofitting will require area-wide initiatives with housing and social services to support tenants and owners who have a long-term-illness or are elderly and may depend on social care, as well as others who may have health problems and would be affected by the high level of disruption and dust if a full refit is required. Municipal direct works departments should be revitalised with a skilled workforce to undertake retrofitting, longer term whole life maintenance, and repowering and upgrading of heat pumps and other equipment.

The role of government must extend beyond ownership and operation of renewable energy to retrofitting the built environment, ensuring an integrated approach to conserving nature and biodiversity, environmental adaptation, and decarbonation of manufacturing, construction, and public transport. It also has a vital role in establishing new public organisations to undertake these functions and ensure they have a trained and skilled workforce with the capacity to maintain, repair, and upgrade renewable energy assets, heat pumps, insulation, and broadband systems as well as extend national grid networks.

Since only 4% of renewable energy projects globally are publicly owned, the importance of increasing public ownership of renewable energy generation and retuning national grids and local distribution networks to public ownership is clear:

- Make the case that renewable energy assets should be publicly owned and operated and also highlight the benefits for workers, service users, local employment and training, and the local/regional economy.

- Governments should establish a National Renewable Energy Agency to increase direct public investment in new renewable energy projects and to nationalise key renewable energy companies and their assets.

- Municipal authorities should seek to fully acquire renewable projects when they are offered for sale on the secondary market, initially targeting small and medium-sized projects to build experience and capacity. They should avoid the acquisition of very small stakes in renewable energy projects. This approach was adopted in the latter stages of the UK’s failed Private Finance Initiative (PPP) programme when some local authorities became minority shareholders with minimum benefit.

- Government and municipal authorities should consider financing the repowering of renewable energy projects on the condition that they obtain a majority stake in the project company.

- Eliminate outsourcing and exploitation through low wage and poor working conditions for employees. Take the initiative for radical improvement in employment terms and conditions at all stages of renewable energy projects. Introduce improved regulations on quality of jobs, employment standards, training, and sourcing of supply chains. Trade unions and pension-fund trustees should re-examine the scale and type of pension-fund investments made in renewable energy projects and the associated risks and alternative investment strategies.

- Integrate power generation and renewable energy technologies, and increase capacity of grid transmission and distribution. Immediately stop the commercialisation of nature and biodiversity, abolish competitive bidding and outsourcing, and maximise public management of these assets. Prevent the forestation of sites near areas of natural beauty, coastal areas, and inland lakes, and avert reduction of food production capacity or productivity. •

References

- Brookfield Renewable Partners LP (2020) Annual Report 2019.

- Equality Commission for Northern Ireland (2010) Section 75 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998: A Guide for Public Authorities.

- Financial Times (2022c) “Brookfield considers spinning off its asset management business,” 11 February.

- REN21 (2021) Renewables 2021: Global Status Report, Paris.

- The Guardian (2022b) Great British Energy: what is it, what would it do and how would it be funded? 27 September.

- Whitfield, D. (2010) Global Auction of Public Assets: Public sector alternatives to the infrastructure market and Public Private Partnerships, Spokesman Books, Nottingham.

- Whitfield, D. (2016) The financial commodification of public infrastructure: The growth of offshore PFI/PPP secondary market infrastructure funds, ESSU Research Report No. 8.

- Whitfield, D. and Smyth, S (2019) Infrastructure Investment – The Emergent PPP Equity Market, Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 90(2) 291-309.

- Whitfield, D. (2023) ESSU Global Renewable Energy Secondary Market Database 2019-2021.