Building a Labour Movement to Take on the Billionaire Class

Joe Burns’ new book, Class Struggle Unionism, reads like pamphlet, with a clear call to transform the union movement in the US (although it is still applicable to Canada). The model for change is one that has deep roots in the radical socialist and anarchist traditions of working class movements from early in the 20th century that has continuously raised it head over the past 120 years or so, in the face of repression, defeats of the left and various forms of ideological and political confusion. Needless to say, it is sorely needed today.

As such, the book is inspirational, educational and, in spite of today’s weak, crisis-ridden and ideologically and organizationally wounded labour movement, provides an optimistic, longer-term vision of a fighting, adversarial and effective labour movement. Its strength, is his description of class struggle unionism, its history, logic, ideological basis, tactical and strategic approach, its general political orientation, and thoughts on how to build it.

In the process, he critiques different forms of unionism, such as business unionism and labour liberalism. His description and critique of the latter is sharp and cogent, given its popularity around the community of left liberal and social democratic union reformers. He includes insights from a number of socialist and radical labour activists and thinkers across various left tendencies and approaches, avoiding the kind of sectarianism that he justly criticizes.

The book calls for building a form of unionism that is rooted in the basic antagonism between the working class and the capitalist class (which he refers to as the ‘billionaires’), and it uses that orientation as a guide for rebuilding, transforming, and growing the union movement. In doing so, he doesn’t avoid dealing with some difficult challenges and contradictions.

The book has some important weaknesses. The political analysis – while rooted in a class struggle, anti-capitalist orientation – is contradictory and comes close to a kind of left populism at times. How worker participation in struggles can lead to the development of class consciousness and a deeper political understanding of the system is also unclear as is the role and nature of working class political organization and electoral participation and how they relate to class struggle unionism.

His view of political institutions and the state tends to be brittle and unidimensional. Finally, there is no reference to one of the critical components of class struggle today – the climate emergency and the role that class struggle unions need to play in transforming societies as eco-socialists.

Class Struggle Unionism

Burns roots his description of class struggle unionism, in the labour theory of value, and Marx’s description of the theft of surplus value that underpins the production of commodities. But impressively, he goes beyond the usual, rather simplistic description of the basis of exploitation by citing Bill Fletcher and Fernando Gapasin in Solidarity Divided, which describes how an entire social surplus is produced by workers yet appropriated by capital for its own power and accumulation and continued reproduction.

The basic antagonism between labour and capital is embedded in capitalist society and serves as the underpinning for class struggle unionism. But Burns is not a class reductionist and doesn’t underestimate the strategic importance of forms of discrimination, linked to systematic racism, sexism and oppression against immigrants.

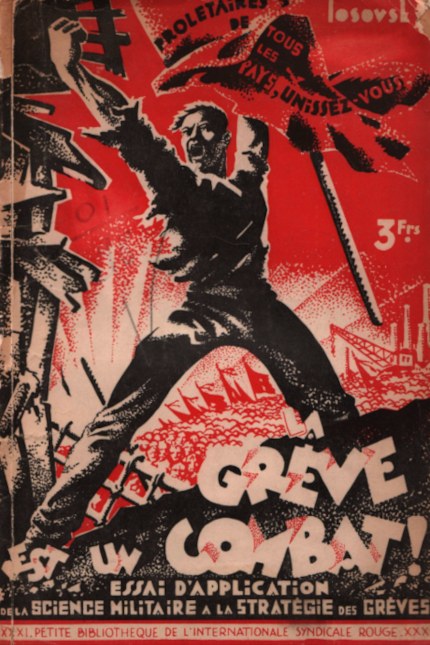

Class struggle unions see this antagonism, and the struggles driven by it as a continuing, ongoing characteristic of the system, and class struggle unionists see collective agreements, or periods of relative labour quiescence, as temporary truces in an ongoing war (this reminds one of some of the materials produced by the Third International in the 1920s and 1930s, such as A. Losovsky’s A Strike is a Battle (La Grève est un Combat).

Burns argues that this “cardinal principle” of class struggle unionism guides the way such unions operate in reality. “The concept of us versus them is at the core of class struggle unionism,” he writes. That is reflected in everything a class struggle union does, from its approach to the overall system, to everyday workplace and community issues. Class struggle unionists promote an understanding amongst the membership of this reality.

This approach to unionism involves: constantly challenging the interests, prerogatives, and practices of employers in the workplace and in society as a whole; fighting to transform working conditions and power in workplaces (which tends to be ignored today by most unions), and not just industrial workplaces; opposing team concept and worker-management “co-operation” programs; advocating militant and collective forms of union action, especially open-ended strikes; a belief that workers should lead their struggles and their unions; challenging the labour bureaucracy – people on the staff of unions and top leaders, especially those who call for accommodation with capital and unprincipled compromises; building rank and file caucuses; and a great deal of scepticism and opposition to reliance on governments and the state.

The constant reference to the importance of workplace struggle and power is a critical and refreshing piece of this picture of class struggle unionism that needs to be emphasized, particularly in modern workplaces of all kinds.

Strikes, Collective Direct Action and the State

Burns places emphasis on the role of mass direct action and especially open-ended strikes. This is so for a number of reasons. First, these collective actions challenge employers in ways that can lead to victories. They directly mobilize the power of workers to stop production, use mass picketing to prevent the use of scabs, develop solidaristic support from other workers, spread struggles across economic sectors and geographical areas, and challenge the use of injunctions and other forms of state repression of striking workers through direct resistance and economic power.

Secondly, workers involved in these battles can learn about key elements of class struggle and the social relations underpinning it: the interests of their direct employers and those who finance them; the importance of using workers’ collective power; the strength of worker solidarity; and the role of the state in backing employers and repressing workers struggles. By implication, workers can also learn that the system of private ownership by “billionaires” itself, needs to be replaced.

Third, they open up the potential to extend the plane of struggle to a wider and higher level and point in the direction of building a different kind of working class movement – one that spreads throughout the class and society.

Arguing for a strategy of open mass strikes has implications for the survival of unions and the bureaucracies and elected figures that lead them. Taking on injunctions, closing down critical economic centres, stopping scabs, and organizing solidaristic support can lead to massive fines and even the punitive prosecution of individuals and potential destruction of a given union. But, as Burns argues, these real risks sometimes are outweighed by the strategic importance of building a different kind of union movement (and a cohort of workers) that will become a weapon for building resistance to capitalism.

Of course, his analysis implies a particular view of the state and in particular, the institutions that regulate labour unions. That view makes sense in many places but can be simplistic and populist in others. I will return to that set of issues later in this review.

Business Unionism and Liberal Labour Unionism

Burns’ description and critique of business unionism and labour liberalism are cogent and thoughtful. Business unionism accepts the legitimacy of the system and the right of capital to own and control the means of production and service delivery. It seeks accommodation with employers’ need to make profits, avoids unnecessary struggle, works to dampen worker aspirations and is politically conservative. Its structures are bureaucratic and top leadership substitute themselves for the members and rank and file – many of the former hang onto their positions for decades at a time.

Business unions see strikes and contract battles as aberrations in what needs to be a peaceful, ongoing relationship. Instead of trying to expand and deepen contract battles, they seek to end them as soon as possible. Management’s control of the workplace is acceptable to business unions, even though they challenge the boss on certain issues.

Most tellingly, according to Burns, business unions see worker dependence on the market success of individual employers (and sectors) as absolutely inviolable and unchallengeable. As a consequence, they adjust worker demands and concerns to accommodate the competitiveness of the employer. Of course, this dependence is not just an “ideology,” but a material reality that every worker instinctively understands. Most often, their livelihoods do depend on their boss’s market success. But a class struggle union seeks to lessen that dependence, all the while arguing that in the long run, a different system would challenge the structural basis of this dependence.

One of the more creative parts of this book is Burns’ critique of labour liberalism. The latter, developed by professional middle class reformers and some former leftists, also seeks to avoid confrontation and direct mass struggles against employers (or the employer class). In fact, it tends to avoid struggles in workplaces and argues for legislative changes, larger social issues (not necessarily tied to class issues and almost used as diversions), organizing new workplaces instead of fighting for existing members (or, better, doing both); working as part of the Democratic Party (in the US context), and relying on NGOs, non-profits and other, non-working class organizational forms.

Their base is in some public sector unions and were very popular with a moderate left and young people unfamiliar with the lives and conditions of workers. Their ideology is liberal in the US sense of that term or moderately social democratic. They avoid mass struggle, such as strikes, and instead, opt for ‘demonstration’ strikes or actions, which seek public (and ruling class) sympathy and support, but avoid confronting the power of the employers and engaging the collective potential of workers. Their campaigns and strategies are developed by staffers, leaders, or are farmed out to progressive consultants.

Burns is critical of the reliance on and role of workers’ centres, since they are not necessarily tied to unions and are divorced from workplaces. When critiquing labour liberalism, he is stubbornly one-sided and harsh in his consideration of workers’ centres, although in other sections of the book, he is more nuanced in evaluating their different structures and roles (it is hard to be so critical of some of the most strategically important centres, such as Immokalee in Florida which led struggles to support farm workers and similar organizations in the Pacific coast and elsewhere).

Developing Class Struggle Unionism

Burns’ analysis of how class struggle unionism can be built – either through transforming existing unions or, more rarely, in forming new ones is fairly solid. Whether one uses the terminology of “militant minority,” or simply builds on a base of the most reliable, respected, and militant workers, one has to start with a relatively small group of workers who are, as we used to say in my days as an implantee in an auto factory, “advanced workers” or have the potential to develop into leaders. As well, there is no way around the daunting reality of today, that the level of militancy, political literacy and class understanding of such workers is generally not high to begin with.

It remains for class struggle activists, or socialists with an understanding of and dedication to building class struggle unions, to work with this stratum, help develop their understanding and competency, and, combining collective experiences in struggle, along with political education (in a non-sectarian manner), to develop a solid and larger cadre of class struggle adherents. Working in a non-sectarian manner with other workers, a movement for transformation of unions can be built.

(As an aside, I don’t see the necessity of his gratuitous attack on Jane McAleavy’s strategic approach of developing leaders and building union power. One would need a microscope to be able to distinguish these different ways of building a corps of activist leaders and growing outward.)

Burns does tackle a number of thorny contradictions here, such as the role of “salts,” left political activists working on the shop floor and serving on the staff of unions. His take on these issues is mature and quite thoughtful. He argues that unlike many in my generation of “implantees,” their role isn’t to provide an intellectually heavy radical political perspective, but a class struggle orientation. One wonders how he would view some of the newer and younger salts that are working in places like Amazon, looking to unionize through creating new unions or as part of existing union organizing and seeking to bring both a class struggle and socialist perspective there.

Contradictions and Weaknesses

Overall, Class Struggle Unionism is an inspiring and refreshingly realistic yet radical take on where unions need to go – and how they might go in that direction. But there are some troubling contradictions and weaknesses.

There is a sense that participation in militant, creative, and long strikes itself automatically leads to the development of class consciousness. Certainly, these experiences, and the necessary preparation for them, provide a key grounding for workers to become open to socialist understandings of class and the structures and relations that underpin capitalism. But it doesn’t happen without exposure to socialist political ideas and education. That requires socialists to work in developing these unions and in these struggles.

Burns clearly demonstrates that historically, communists and other socialists played a leading role in building the class struggle trend. But today, it also requires socialist to work in and around the union movement, helping to summarize experiences, learning with co-workers, and finding ways of providing education about the social and political relations of the system, and potential alternatives. As we all know, experience doesn’t necessarily lead to constructive and radical conclusions by itself: victories and defeats can lead participants in all kinds of directions. The lack of cohorts of class conscious workers, let alone socialist cadre that came out of the experiences of the Wisconsin movement, Occupy Wall Street, anti-globalization demonstrations, and the Ontario Days of Action speaks volumes about this. But Burns spends little space in the book about the necessity of socialists playing this role, and it begs the question of where it will come from.

Burns’ description of different kinds of working class politics avoids taking a position on the need for socialists to organize politically and engage with workers, and although he criticizes syndicalism, his analysis at times comes perilously close to embracing it. To be fair, though, in the end, he concedes that unions are limited in what they can accomplish: “Even if unions don’t bring about social revolution, they play an important part in furthering solidarity and class consciousness.”

But that leaves us without a sense of the importance of developing a socialist political presence, organizing, educating, and eventually engaging in the electoral sphere in some form of party, independently or with others. This is related to his view of the bourgeois state.

Burns’ view of the bourgeois state is contradictory. At times, it is portrayed as anti-union and an implacable enemy. At other times, he employs a more nuanced analysis. When dealing with strikes and mass actions, he argues that the existing state is anti-union and a tool of the billionaires. Certainly, when fighting against repressive mechanisms set up to regulate and limit the boundaries of working class institutions, he is right on the money.

But in a larger sense, this is an oversimplification and rather than explaining the role of the capitalist state in this regard, it is too populist to politically arm class struggle unionists and the rank-and-file workers they are seeking to mobilize and educate. The American bourgeois state is certainly there to guarantee that whatever forms of worker resistance and organizing exist remain subservient to and remain within the boundaries of private capitalist accumulation and competitiveness. The level of direct repression can and does vary with the power of the working class to pressure the state and capital, and the power of capital to wield that repression. Components of the state that regulate labour, such as the National Labor Relations Board, are not neutral, but neither are they necessarily “anti-union.” And their origins in the New Deal era were seen as real gains.

They reflect the need of the state to limit the power and independence of the labour movement and workers, all the while embodying the need to accept some level of the legitimacy of unions. Arguing that they are “anti-union” (as the Taft-Hartley Act passed in the late 1940s clearly was) narrows any possibility of pursuing reforms and efforts to wage class struggle to limit their repressive role and democratize them as much as possible in a capitalist system.

Using state institutions to legitimate unions simultaneously comes with control, regulation and limitation, which is a built-in contradiction that unions have faced even before their partial legitimation during the Roosevelt administration. Labour law can’t be ignored and unionists – whether of the class struggle or business variety – have to wage struggles to transform and limit and violate, where possible and necessary, existing labour laws. In fairness, though, in the end Burns doesn’t argue that unions should completely ignore labour law and the reform components of the state. They should maintain both a healthy skepticism and critical independence of them, and especially keep from becoming adjuncts of the reformist wing of the Democratic Party.

There is another problematic in this book: the lack of any reference to the climate crisis which is so clearly linked to the capitalist system and the lives of working class people – and therefore, is a critical terrain of class struggle. This is more than something simply left out. To be a socialist today is to be an eco-socialist, and the challenge to the ‘billionaires’ and their system must also include a transformation of our relationship to the planet’s ecosystems. The role of the working class and especially unions must be redefined in relation to both the economy and social life and therefore, it needs to be a key battle across the union movement.

How can a class struggle union movement handle the transitions necessary to facilitate a climate friendly overhaul of social life? How would a movement partially dependent on the work of employers who are driving the climate crisis itself build a class struggle to fundamentally transform or eliminate economic sectors in ways that facilitate a different and better life for the working class as a whole? For example, how would a class struggle approach to transportation deal with the move of the auto companies toward massive production of electric cars, as opposed to mass transit expansion?

This leaves out some of the other contradictions between business unionists, some of whose members are currently tied to existing forms of economic or extractive industries (clear-cutting old growth forests, forms of resource extraction, oil and gas) and those who argue for transitioning away from the latter. The horrible shenanigans of some of the business unionists in BC’s disenfranchisement of an environmentalist in the provincial NDP leadership contest – shamelessly modelled on the British Labour Party attack on Jeremy Corbyn and the left there – provides a negative example.

Wouldn’t a class struggle and eco-socialist approach provide a way of dealing with these contradictions? Does transitioning beyond these forms of economic activity require a socialist and anti-capitalist perspective that needs working class leadership? Given the urgency and complexity of building in these directions, shouldn’t class struggle unionists engage in the debates about what kinds of alternatives are necessary and possible and start integrating these approaches in their ideological and organizing practices?

Also missing in the book are references to the relationships necessary to build (and contradictions to handle) between class struggle unionists, eco-socialists and Indigenous peoples and nations, who live and claim some form of sovereignty and voice, or veto, over many of the areas affected by the above.

One would think that Burns’ take on these issues would certainly be constructive, useful, and contribute to the deepening of what class struggle unionism should look like. At the very least, his description of class struggle unionism can provide a guide for how to approach these issues.

In Lieu of Conclusion

Overall, I thoroughly recommend this book for both its critical and inspirational truths, as well as the questions and contradictions it raises. Sitting at my desk in Ontario, I am reflecting on the recent action of a 55,000 member CUPE local, which, in the face of large fines, resisted the Ford government’s invocation of the notwithstanding clause just over a week ago. This may soon spread across the sector – with its disparate unions and the Ontario labour movement at large. The Ontario Public Service Employee’s Union unit of education workers was a major supporter of CUPE.

Hopefully it may eventually be followed by health care workers – in the face of draconian legislation by the provincial government against all public sector workers.

I wonder what a class struggle union approach would accomplish. What kinds of political education would be necessary to prepare the membership, parents, students, the larger working class and other unions to successfully build for a major political as well as economic battle? What role would socialists play, in helping to prepare the terrain, engage with co-workers in the struggles, helping to push it forward, and ultimately, facilitating and shaping a summary of the lessons learned in the struggle, and contributing ideas for how to go on? Could it eventually allow for building a class struggle current that would point toward a different, more radical ant-capitalist politics, and dare I say, calls for a socialist political organization of some kind?

Interestingly enough, many of above characteristics of class struggle unionism have been applied in the CUPE education assistants local (and this helps to explain their strength, unity and preparedness), but this not the case in the other education and teacher unions.

Clearly, Class Struggle Unionism is an extremely valuable tool for approaching such a moment and others like it sure to come. •

This article first published on the Canadian Dimension website.