Unfinished Business: The Hassan Diab Affair Continues

Many in Ottawa may remember the day he returned to Canada from France. A crowd of longstanding supporters, his wife, and little children received him with open arms and crimson flowers. It was a euphoric moment. Dr. Hassan Diab, the man who was falsely accused of carrying out the 1980 bombing of the Paris synagogue on rue Copernic, who was wrongly extradited in 2014 on the basis of an egregiously flawed handwriting analysis, and who spent more than three years in solitary confinement without charge or formal trial, was finally released on January 12, 2018, from France’s Fleury-Mérogis Prison.

Two French investigative judges, Jean-Marc Herbaut and Richard Foltzer, had studied Diab’s case meticulously over several years (the former even made a trip to Lebanon to interview eye witnesses), and finally declared, “There is no evidence to indicate, or even imply, that … investigations will enable [the gathering of] further incriminating evidence against him.”

When news of Diab’s dismissal was first shared, the halls of the prison rang with the cries of his fellow inmates: “Liberté, liberté!” they shouted in rhythmic unison. Over 38 months, and in close proximity, these men came to know the person in their midst: an anomaly in a maximum-security prison, a man of generous humanity, stoic strength, and moral rectitude. The label “terrorist” slapped on him by Canadian and French judiciaries and their adherents was at once absurd and baseless. Like the French investigative judges Herbaut and Foltzer, the inmates of Fleury-Mérogis prison knew that Diab was the victim of a false and damning allegation. He was decidedly not the bomber being sought by French authorities. Diab was 26 in October 1980. The bomber was between 40 and 45. Diab’s fingerprints did not match those of the suspect. He was in Beirut when the attack on the synagogue took place.

Mistakes and False Accusations

Ostensibly, this was a case of mistaken identity. Yet, with the hindsight of fourteen harrowing years, that description is too charitable. In 2022, it is difficult to treat the false accusation levelled at Diab as an innocent mistake. The prosecutors were surely aware of certain glaring discrepancies between a hotel clerk’s eye-witness description of the bomber and that of Diab. Arguably, they felt confident they could elide those disparities, courtesy of a Canadian extradition law that favoured their objective: i.e., to punish a scapegoat in order to assuage the grief of the rue Copernic survivors. Under intensifying pressure from the victims’ lobby (which today includes five French associations), the prosecutors’ mission had to be carried out expeditiously. In 2008, a culprit had to be found and sentenced without further delay. It had been many years, and the case had still not been solved.

Happily, for the French authorities, reforms in Canada’s extradition law during the 1990s helped to fast track and, in the words of Paul Slansky (member of the Criminal Lawyers’ Association of Ontario), rubber stamp extradition requests. The Canadian extradition law allowed the French to make their request, virtually unimpeded; it enabled them to invoke allegations based on unsworn and unsourced intelligence (10:06 -11:16). But just as they were graced with full liberty to use murkily extorted hearsay, so Diab’s liberty was utterly expunged. He was forbidden to challenge the requesting state’s allegations with an alibi. The truth that he was not in France at the time of the bombing would be a major casualty in the prosecutors’ case against him. It would be stifled in the darkness of secrecy.

Canadians who have followed Diab’s story know that his jubilant return to Canada in 2018 did not mark the end of his ordeal. Between 2018 and 2021, he enjoyed three years of grace. But during that lull, French prosecutors quickly launched an appeal process. To the horror of many, the appeal was upheld. In May of 2021, France’s highest court ruled that Hassan Diab stand trial. Today, in 2022, Canadians may ask how Diab’s case got reversed from glorious vindication in 2018 to a nightmarish condemnation in 2021? After all, allegations against him had been entirely discredited by French investigative judges and by his eminently capable lawyer, Don Bayne. Even Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said on June 20, 2018, that “we have to recognize first of all that what happened to him [Dr. Diab] never should have happened … and make sure that it never happens again” (4:58-5:19).

But what happened did happen and with fourteen years of hindsight, it seems scarcely accidental. For the entire Diab case was the result of an implacable will – governed by a victims’ lobby and a Zeitgeist of anti-terror laws – to find a culprit for the 1980 bombing even if this meant conceiving a fictional terrorist, whose name and sinister reputation would be plastered on the innocent Diab. This was not a case of mistaken identity. It was a brain-spun identity, created as a stand-in for the elusive culprit. Yet, such deception could only survive if it rested on a network of other falsehoods: e.g., misrepresentations, denials, and suppressions of exculpatory evidence. Close scrutiny of the case reveals precisely that – a host of irregularities, all now exposed, but which initially helped to maintain the illusion that Diab was the bomber.

The Facts of the Case

1) In 2008, when it made an extradition request to Canada, France lied: it stated that no “usable fingerprint traces could be found on the hotel card personally handled by the bomber.” In 2007, prior to submitting their extradition request, the French authorities had, in fact, located usable fingerprints. The lie was only disclosed in 2018 by the two French investigative judges, Herbaut and Foltzer. But France never corrected its false statement and thus misled the Canadian Superior Court of Justice, the Court of Appeal for Ontario, and the Supreme Court of Canada.

2) The first sample of handwriting used for analysis purported to be Hassan Diab’s. It was not. It was his former wife’s. France had thus to withdraw two reports which had been discredited by this faulty comparison. French prosecutors then issued a third report, known as the “Bisotti report.” It, too, was shown by several international experts to be worthless.

3) In 2021, hoping to invalidate the arguments of the international experts and thus reinstate flimsy handwriting evidence, France’s Court of Appeal called on French experts to study the flawed Bisotti report. Contrary to the court’s expectations, the French experts concurred with all the verdicts provided by the defence’s analysts: the Bisotti report, they agreed, was thoroughly unsound.

4) In 2021, when the French Court of Appeal overruled the dismissal order that released Diab in 2018, its decision was awash in discrepancies and errors. Diab’s lawyer, Don Bayne, responded with a meticulous account of the report’s carelessness, twisted facts, fanciful speculations, and contradictory claims, including the reinstatement of the infamous Bisotti report.

If one cannot argue that such inaccuracies and acts of mendacity were part of a master plan, one can nonetheless say that they reflect a tacit consensus: i.e., that the solution to the mystery bombing had to be found at any price, and French authorities had invested too much in their fictional terrorist – in their one suspect – to relinquish the job and admit gross failure. With this intransigence, they would run roughshod over facts and callously abuse the rights of an innocent Canadian.

Instances of negligence, erroneous reports, and deceit by French authorities also speak to France’s contempt towards Canada. The French prosecutors put forward a request with insufficient evidence, unfit for trial, assuming they could pull the wool over Canadian eyes. Meanwhile, it mattered not to Canadian authorities that Diab, a Canadian citizen, would be sacrificed on false grounds for the benefit of France. Remarks by former Minister of Justice Rob Nicholson made this clear when he described the defence’s serious concerns about Diab’s fate in France as overly technical and “finicky” (1:12:09 – 1:12:17). In correspondence, Nicholson also told Diab’s lawyer, Don Bayne, that “the guilt or innocence of the person sought is not a relevant consideration” in the context of Canada’s extradition law (April 4, 2012). Exculpatory evidence could thus be suppressed with impunity. Such is the cold and cruel inhumanity of this law, and when applied to a Canadian of Lebanese extraction, we might call such cruelty racist.

Role of Racist System

Over the past fourteen years, the role that racism has played in the Diab Affair has been given short shrift. While there have been occasional references to the anti-terror, anti-Arab climate in France and Stephen Harper’s Canada, the main focus has been on the convoluted Diab saga, and on the flaws of an extradition law that desperately needs reforming. But racism has, in fact, permeated the court system, seeped into the action of police authorities, and stained certain remarks uttered in court. The Ontario Court of Appeal, for example, claimed that Diab was not a Canadian citizen in 1980 (1:37:37 -1:37:50), implying that he was not worthy of Canada’s full protection.

Racism may be palpable to the victim, but it is not easily proven by singular empirical facts or occasional utterances. That said, the disparaging treatment of Hassan Diab and his wife, Rania Tfaily, (18:00 – 19:49) by the RCMP, CSIS, prosecutors, and prison guards between 2008 and 2014 (29:00 – 46:04) can be readily chalked up to anti-Arab bigotry. The contemptuous conduct displayed towards the couple has been consistent and persistent, shaping the direction of the saga henceforward. Even when facts spoke in Diab’s favour, every level of court failed him. French authorities had planned on his extradition and incarceration, and they would brook no contradiction in judicial proceedings. It was as if Diab’s fate had been pre-ordained and his liberty excluded from a master design.

But Diab’s release by French investigative judges Herbaut and Foltzer was not part of a scheme. That dismissal, being a precedent-setting decision in the history of French terrorist cases, constituted an unforeseen setback in the prosecutors’ efforts to condemn Diab. French authorities had perhaps not expected that their investigative judges would affirm Diab’s innocence given the country’s anti-terror crackdown. They had perhaps not anticipated that Diab would receive the defence of a stellar lawyer such as Don Bayne, who exposed the French Court of Appeal’s embarrassingly shoddy report. Could they have ever imagined that Diab, so reviled initially by the mainstream press, would see his supporters grow in numbers over the years from a trickle to a torrent of advocates?

In her book, Justice for Some, Noura Erakat describes the law as the sail of a boat.

“Like the sail of a boat, the law guarantees motion but not direction. Legal work together with political mobilization, by individuals, organizations, and states, is the wind that determines direction. The law is not loyal to any outcome or player, despite its bias towards the most powerful states. The only promise it makes is to change and serve the interests of the most effective actors.”

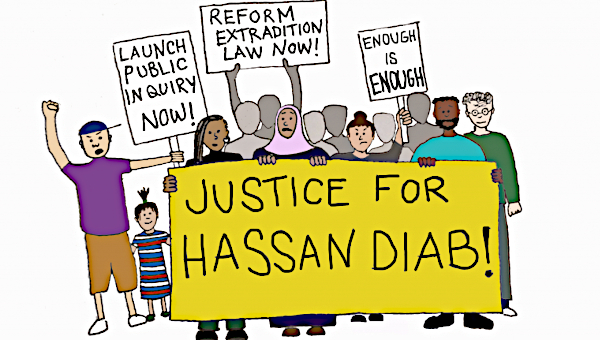

If the courts have failed Diab, repeatedly steering his boat in the wrong direction, it will be up to Canadians of conscience to be those “effective actors.” Through public pressure, such persons will need to redirect the course of events. Like the winds that move the boat’s sail in the direction of justice, these “effective actors” will need to outdo the winds from France by vigorously exhorting the Trudeau government to save Diab from a second extradition, and from the consequences of a trial, now set for April 2023.

The imperative effort to save Hassan Diab is the task of all Canadians who care about human rights. We are all imperilled by extradition laws and by the states that deploy them. Diab’s ordeal incarnates a shared vulnerability, and his salvation is the liberty of all citizens. Only a powerful collective voice from Canadians at large will guarantee his freedom and the justice that underpins it. •