The Abortion Crisis and the Legacy of Activism

Beginning September 1, 2021, the state of Texas enacted the most aggressive challenge to Roe v. Wade (1973) since the decision was handed down by a Court packed with justices nominated by Republican presidents (Majority, Republican nominees in bold: Blackman/Nixon, Brennan/Eisenhower, Burger/Nixon, Douglas/FDR, Marshall/Johnson, Powell/Nixon, Stewart/Eisenhower; dissenting, Rehnquist/Nixon, White/Kennedy).

That Roe came from a mostly Republican-appointed Court is important when one considers the argument that the pro-choice movement can rely (only) on Democratic politicians and that electing Democrats is vital to the preservation of abortion rights. While it is true that Democrats are more likely to nominate pro-abortion justices, relying on the electoral process to protect abortion justice is untenable. The record of Supreme Court decisions also shows how even a conservative Court is affected by pressure from below. In this light, it is notable that President Joe Biden and other Democrats are urging the reversal of the 1976 Hyde Amendment, which prohibited the federal government from providing funds for women receiving public assistance to get an abortion. This shift in the stance of the party comes in the wake of social movements demanding race and gender justice.

Erosion of Roe v. Wade

The history of the erosion of Roe v. Wade is marked by misguided and failed movement reliance on electoral politics and legalistic strategy. Since 1973, a number of states have enacted abortion restrictions that have been upheld by the Supreme Court. These restrictions include parental consent laws and spousal notification and consent laws. Restrictions on providers of and facilities for abortion have made abortion virtually unobtainable in the vast majority of counties in the United States, barring many young or indigent pregnant persons who cannot afford to travel from accessing this vital service. Increasing term restrictions on abortion means that women, who, under Roe, could seek abortion in the second or third trimester in case of threat to fetal or maternal health, must carry unwanted pregnancies to term at the risk of death.

Restrictions on abortion especially target young people, oppressed minorities, immigrants, and the poor – those who are most vulnerable and who urgently need control over their reproductive lives.

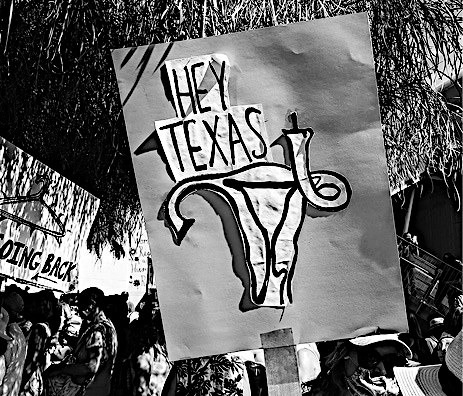

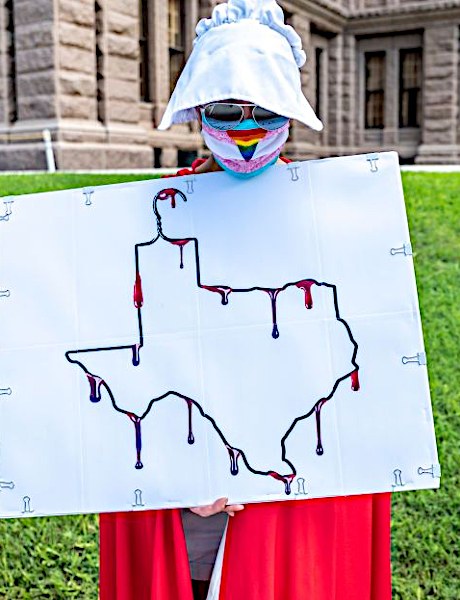

The new Texas law goes much farther in restricting reproductive freedom. It bans most abortions after six weeks of pregnancy, a point at which most people do not even know that they are pregnant. It does not make exceptions in the case of rape or incest. The most chilling aspect of this law is that it empowers vigilantes to sue their neighbors, family members, doctors, and anyone else who supports a woman seeking abortion, making abortion incredibly dangerous, not only to people seeking one but also to the already fragile and meager infrastructure making access to abortion possible.

The criminalization of abortion in Texas, and looming threats to access in 26 other states, harken back ominously to pre-Roe times, when abortion was a crime. Historian Leslie Reagan’s essential book When Abortion Was a Crime (University of California Press, 1996) documents how thousands of women filled septic wards in hospitals following infections caused by illegal abortions they were forced to seek. Police interrogated women who lay dying about the circumstances of their abortions, intending to arrest and prosecute the doctors and laypeople who attempted to provide abortions, along with anyone else who supported the desperate women.

These women sought abortions whether or not they were legal. Criminalization does not prevent abortion – it only makes it life-threatening.

Before Roe When Abortions were Illegal

Reagan has spoken up about the Texas law. In an op-ed in the Washington Post, she explained the situation that women found themselves in before Roe:

“Law enforcement used horrifying and invasive methods to obtain evidence of criminal abortion from women, including incarceration and bodily invasion. At times, women were held in jail as hostile witnesses, then forced to testify against their abortion provider at trial.

“In 1947, for example, Chicago police captured eight women outside the building of a midwife-abortionist, put them in police cars, and drove them to a medical office for internal pelvic examinations by a doctor searching for evidence of an abortion in progress. The state claimed that the police ‘escorted’ the women, who ‘consented’ to the exams and volunteered to testify. But there was nothing voluntary about the women’s role in this investigation; it was entirely coercive. Police had cursed at them, threatened to call a paddy wagon if they resisted, and manhandled them into police cars.

“Coroners and prosecutors questioned women’s families and associates, exposing their most intimate experiences, sometimes to partners or family members who could inflict shame and mental or even physical harm if they disapproved.

“Even if women never faced criminal sanction, law enforcement routinely punished them in gendered ways, through public humiliation and threats, for seeking abortion. This public naming and shaming warned all women of the danger of being caught by the police.”

Today, Reagan concludes, women and their families again face invasive, humiliating, and dangerous restrictions on abortion, now defined explicitly, once again, as a crime.

How did we get to this terrifying point? One reason for the steady erosion of the right to abortion, and now its outright criminalization in Texas, is the increasing and unwarranted faith of mainstream pro-choice organizations (such as National Abortion Rights Action League and Planned Parenthood) in electoral politics, trusting that elected Democrats will nominate and support pro-choice judges (even as Hillary Clinton protested that abortion should be “safe, legal, and rare”). Both history and personal experience put the lie to these claims.

Historic Demonstration in Texas

In 2013, I was part of the historic demonstration and occupation of the Texas Capitol by thousands of abortion rights activists, people of all genders, sexual orientations, ages, races, and backgrounds. The occupation was triggered by a filibuster by Texas State Senator Wendy Davis against draconian anti-abortion legislation set to pass during the summer session.

Demonstrators crammed the rotunda, meeting rooms, and all of the circular decks below the dome, most wearing the color orange and carrying signs reading, “We Won’t Go Back!” and “Stop the War on Women!” The Legislature was running out of time to pass their bill under a law that said votes had to take place before midnight. The roar of the crowd into the evening was deafening as the demonstrators, denounced by conservatives as an “unruly mob,” chanted and sang without pause. As midnight approached, demonstrators crammed against the doors of the legislative chamber and roared. The clock struck midnight – in one reporter’s words, the crowd had “shouted the bill to death.”

My own experience in that demonstration was one of deep empowerment. Acoustic science and common sense tell us that sound is a wave that exerts physical pressure. In a literally hair-raising moment, I could feel the force of the voices of everyone around me as a compelling pressure toward unity and power. When the bill died, there was mass revelry and intense political conversation about the ways forward. The bill was to be taken up again in a few days, in a second emergency legislative session where it would surely pass if there were no protest.

What happened next was a tragedy. While those assembled debated the possibility of an ongoing Capitol occupation, leaders in the abortion-rights mainstream and Democratic Party urged the crowd to disperse to continue activity outside. What was outside? A political rally for Wendy Davis and other politicians. Disoriented, activists flowed out of the Capitol building and onto the lawn. The unruly mob that shouted a bill to death went down in a demoralizing whimper.

I had been in the halls of the Capitol with hundreds of radicals among the thousands-strong crowd. We attempted to tell others about the history of activism that had won Roe in the first place, how thousands of people had taken to the street to demand federal legalization of safe abortion (and won, despite the composition of the Court). We talked about how we had defended abortion clinics against right-wing vigilantes across the country over a period of decades. We talked about our personal histories of activism.

My political consciousness and activism came into being in the abortion struggle. In the fall of 1991, in Iowa City, Iowa, I helped to lead (along with Anne-Marie Gill and many others) a weeks-long defense of the Emma Goldman Clinic, which had been targeted by Operation Rescue. My daughter had just been born the fall before, and marching in front of the clinic with a baby on my hip drew some attention. (Now it is more common to see people with young children at abortion-justice protests.) We formed the group Action for Abortion Rights. We won that battle, ousting the anti-abortion terrorists with the chant “We are not Wichita!” (Operation Rescue had been victorious in that Kansas city.)

Pretty soon, I connected my own abortion and the mobilization against the right to a broader socialist politics that explained how control of reproduction in the heteronormative nuclear family served as a buttress of a capitalist society bent on privatizing social responsibility. How else to justify the nonexistence of social-welfare policies, anti-discrimination laws, fair housing, and the provisioning of all the necessities of life for ordinary people? The idealized private family (itself largely a mythic, dubious aspiration), alongside an ideology of maternal domesticity and care, became the excuse for the existence of so much concentrated wealth alongside so much mass precarity. The policing of reproduction was part-and-parcel of that system, which bore no responsibility for the workers whose labor it exploited.

The decades since then have witnessed faithful, militant, ongoing defense of the right to abortion. In New York and Chicago (among many other places), militant activists are still facing down right-wing terrorists at our clinics. After the passage of the Texas law, activists marched around the country to protest a return to the days before Roe.

Meanwhile, in the wake of two years of mass protest, the Mexican Supreme Court decriminalized abortion in September 2021. The effects of that ruling are still uneven across the diverse states of Mexico, but people there are still fighting. The irony of this victory alongside the horror unfolding next door in Texas is not lost on us.

Today, we use the language of “abortion justice” to capture the full meaning of reproductive freedom and the oppressive interests behind denying it. We emphasize the disparate impacts of criminalization – not only of abortion, but of existence – on people of color and the poor. We emphasize now that it is not only women whose reproductive agency we champion. Diversely gendered bodies are capable of pregnancy and childbirth, and kinship is expressed well beyond the norms of private familialism. The recognition of the intersections of gender identity and expression, sexuality, race, nation, and class in our shared fight against the policing of our bodies gives us the power of solidarity. It connects our fight for abortion justice to the broader fight against capitalism and for a world in which all of our bodies are free. •

This article first published on the New Politics website.