What Future for Progressive Politics in South Korea?

With 2022 beginning, South Korea’s left remains extremely divided and politically fragmented. In terms of institutional politics, the only left-wing party in parliament is Shim Sang-jung’s Justice Party (JP), nominally the third party in parliament with just 6 seats out of 295. Unfortunately, JP is the exclusive representative of progressive politics in South Korea’s parliament. Moreover, and in spite of its moderate position, it is evident that JP’s links with labour and popular movements are quite thin and fragile. Some Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU) unionists are party members, but most labour and social movement leaders and activists do not belong to JP.

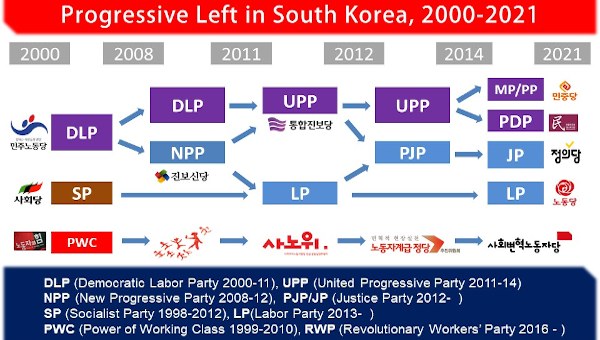

The over-representation of JP in progressive politics is a tragic result of the political collapse of the National Liberation (NL) tendency-led Unified Progressive Party (UPP), which has no seats in parliament and is struggling to politically survive after the party’s arbitrary and forceful dissolution by the Park Geun-hye government in 2013. Though this party remains organisationally strong, in a relative sense, and influential among labour and popular movements, its power in comparison to the previous Democratic Labour Party (DLP) was tremendously weakened. The DLP-UPP years has long gone.

Other small parties and political groups exist, but their organisational strength is weak and their influence limited. More recently, some projects for reinvigorating political militancy are being initiated in light of the upcoming 2022 presidential election. But the various sections of the extra-parliamentary left also face an uphill struggle for survival.

Overall, the political terrain on South Korea’s left is extremely barren. Historically, we are seeing the end of a period: the culmination of the historic failure of a three-decade-long project to build a radical left party that could represent labour and popular sectors and position itself as an alternative to bourgeois politics.

What happened to progressive politics in South Korea? Is there any future left for progressives? Below, we will attempt to summarise the historical trajectories and diagnose the present situation of progressive parties and political groups. We will also analyse South Korean radical politics in general, and search for possible alternative paths for a new radical left-wing party that is deeply rooted in labour and popular movements.

Shim SJ and the Justice Party

JP is a small party and Shim Sang-jung (Shim SJ) is the party’s only popularly-known leader after Roh Hoe-chan committed suicide in 2018 rather than be arrested for bribery.

Even though it originally emerged from the labour and social movements, JP is essentially an electoralist party that limits all of its activities to within the legal framework. Shim SJ was secretary-general of KMWF, a metalworkers’ union, and played a key role in trade union politics in the late 1980s and 1990s.

JP’s links with the movements are rather weak as a result of a strategic choice adopted by Shim SJ. After entering party politics, Shim SJ’s priority was always her own personal interests and career; the movements or party became a secondary concern. For example, she said nothing to Dan Byeong-ho, her former KCTU leader, when she left the DLP to form the New Progressive Party (NPP).

Though the party is technically a nationwide organisation, JP is hardly visible at the local level, except at election times, and often fails to stand candidates in all regions or local constituencies. Shim SJ is the only MP elected from the constituency ballot; all the other JP MPs were elected from the proportional list. JP’s survival heavily depends on Shim SJ’s media exposure and poll ratings, and not on its organisational strength or links with labour and social movements.

JP had high expectations for the 2020 general election, due to the fact it was polling 10 percent. However, the ruling party’s electoral manœuvre to set up a satellite party for the proportional list dashed the JP’s high hope. JP ultimately won only 6 seats, the same amount it had obtained at the 2016 election, when it won 2 MPs from the constituency and 4 MPs from the proportional list.

The party revolves around its supreme leader, Shim SJ, who decides everything. For example, the party list for the elections was decided on her personal taste. Shim SJ will be running for president a fourth time in 2022, but is polling less than 3 percent. Her constant drift to the right has led to many complaints from party members, not to mention her former comrades.

UPP: A Political Suicide

In August 2013, South Korea’s intelligence agency, the National Intelligence Service (NIS), arrested Unified Progressive Party lawmaker Lee Seok-Ki (Lee SK) for plotting to overthrow the government if war broke out with North Korea. The case against him was a comic-tragic fiasco, as it was based purely on a fictional, nostalgic plan that, in legal terms, was hardly a basis for prosecution.

However, the witch hunt campaign launched by Park Geun-hye’s government worked and, eventually, in 2014, the UPP was dissolved by the Constitutional Court on the pretext that the UPP was an “enemy-beneficial organisation.”

Lee SK was an unknown leader of the pro-North Korea local group, Gyeonggi Dongbu Yeonhap. His ambition to enter parliament led him to commit electoral fraud during the process of electing candidates for the UPP’s proportional list. As a result, the party was hit hard politically, leaving its ranks severely divided.

However, the Lee SK case exposed the pro-North Korea tendency’s double play. While seemingly pursuing a reformist line in institutional politics, key decisions were being made by leaders of a clandestine, informal network.

Historically, the NL tendency has rejected the concept of a party-building project on the basis that what is needed in South Korea is a united front! However, based on internal consensus, NL groups began to join the DLP en masse. As the DLP consolidated itself, showing signs of potential for political success, group after group from the NL tendency joined the party and gradually grew into the hegemonic tendency with the DLP.

Symbolic incident was unknown Lee J.H’s rise to the top leadership, after Kwon Young-gil’s (Kwon YG) failure in the 2007 presidential election. She was young and unknown, but in the conjuncture of the party crisis, she was chosen by informal leadership. Her election was also the NL groups’ move to take control of the party, replacing celebrities such as Kwon YG while promoting Lee SK, until then an underground figure.

This top-down, behind-the-scene takeover of the party’s leadership was strongly rejected by diverse sectors within the party, as well as by the People’s Democracy (PD) tendency. NL groups systemically organised electoral fraud in the party primaries, with this undemocratic practice adding fuel to the existing fire of NL-PD disputes.

Though the UPP was an attempt to unify the divided parties, it ultimately led to another split. In the 2012 election, UPP won 13 seats, and Lee SK was one of them, though he was hardly known amongst party member, not to mention of general public. However, after the election, the dissident PD tendency split and formed the Progressive Justice Party, later renaming itself JP.

Meanwhile, NIS’s illegal operation succeeded in recording secret meeting attended by Lee SK that led to his arrest, along with a number of his close supporters. While the UPP’s dissolution was, on the surface, a case of political repression by the anti-communist conservative government, from the political and organisational aspect, it was the result of a political suicide committed by the NL tendency.

Former UPP members later regrouped and formed a couple of parties, such as the Progressive Party (former People’s Party) and the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). However, as long as the stigma of Kim-Il-sung-ism (KISism) lingers on, the political revival of the NL tendency as a party seems beyond reach, and possibilities of surviving as a party remain close to nil.

| Presidential elections | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Candidate | Party | Votes | Percentage | Rank |

| 1997 | Gwon YG | PV21 | 306,026 | 1.19% | 4 |

| 2002 | Gwon YG | DLP | 957,148 | 3.9% | 3 |

| 2007 | Gwon YG | DLP | 712,121 | 3.2% | 5 |

| 2012 | Lee JH | DLP | resigned | ||

| 2017 | Shim SJ | JP | 2,017,458 | 6.17% | 5 |

From DLP to UPP: Some Historical Background

The Democratic Labour Party (DLP) was formed in 2000 as part of the KCTU’s dual organising project for building industrial unions and a working-class party. Initially, a moderate PD tendency dominated, based on its strong links with trade unions, but systematic intervention by NL groups led to a change in its internal politics.

The 2004 general election was a watershed moment for the DLP. In a context of political crisis driven by Roh Moo-hyun’s impeachment and its subsequent reversal, the DLP succeeded in securing parliamentary seats for the first time. As a parliamentary party, the DLP raised the expectation of workers and trade unionists. In that sense, the 2004 election was an apex of the DLP’s electoral performance.

However, electoral success and the rise of NL groups’ into a hegemonic tendency within the party proved to be a poison chalice for the DLP. The pursuit of political careers and ambition for parliament seats shifted the party toward electoralism. Constant internal disputes over various issues became the main focus of party activities and internal politics.

During the process in which the DLP became the UPP, two major splits occurred in 2008 and 2011, leading to the party’s further fragmentation. The 2008 crisis occurred due to the failure of the 2007 presidential election campaign and Kwon YG’s poor performance. With the leadership refusing to entertain any self-criticism, a minority group split off and formed the NPP.

The result of the 2008 general election was also a great disappointment, with the DLP’s number of seats reduced to 5 (the NPP failed to win any seats). Both parties were hit hard by the results, with subsequent disputes and split that impacted not only the parties but progressive politics more broadly.

In an attempt to overcome the crisis and recover the credibility of progressive politics, the DLP issued a call for the unity of progressive parties. In response, Roe HC and Shim SJ, who were involved with the NPP, left to joined the move to build a united party, the UPP. For Shim and Roe, the NPP had proved hopeless in re-securing parliamentary seats. By joining the UPP, they hoped to raise their chances of reentering parliament.

The rest of the NPP refused to join UPP, and later renamed itself the Labour Party, though ironic enough, as its labour base was weak and fragile. The marginalisation of NPP/LP was inevitable; without celebrities or a robust organisational base, NPP/LP had little chance of securing its own space within institutional politics and popular movement in general.

In 2011, the UPP was driven into a factional dispute over candidates for the proportional list ahead of the 2012 election. Given the possibility of winning constituency seats was close to nil, with the exception of a few party celebrities such as Kwon YG, Shim SJ and Roe HC, the dispute over the party list blew up. In the course of the confrontation, Lee SK emerged as a key figure. With the revelations that electoral fraud had occurred in the primaries, the party entered into another crisis.

Attempts to purge and renew the party failed due to NL resistance, leading Roe HC and Shim SJ to split again and build a new party, PJP, later JP after the party dropped the word progressive from its name.

In the 2012 general election, the UPP seemingly recovered its electoral strength, winning 13 seats. However, its success was not the result of the party’s own growth but rather its electoral alliance with liberals. Democratic Party (DP) concessions allowed UPP to win 7 constituency seats. However, the UPP’s success exposed it to NIS operations and media scrutiny, with the Lee SK case instigated a long process that eventually led to its dissolution.

Though the trajectory of the DLP-UPP showed some potential for progressive politics in what has been a historically anti-communist society, the NL’s poisonous strategy of allying with liberals and joining a liberal coalition government, in case liberals won the power, led to its eventual political suicide.

Historically, the failure of the revolution in 1987, though a huge victory to liberals, did tremendous damage to popular movements and progressive politics. Moreover, the hijacking by the NL tendency of the KCTU-DLP’s project for progressive politics fuelled political confusion and demoralisation.

The historic failure of the DLP-UPP project reconfirms the dead end of the legalist-electoralist strategy and its failure to combine with social and labour movements. The NLs and its collaborators fell into a trap of political careerism, and thus, many former KCTU leaders joined the liberal DP for their own personal interest and careers.

With the failure of this 25-year long project, South Korea’s working class has no political wing to represent them. Political ostracisation of NL groups and the moderation of PD groups further killed off the potential for independent working-class and socialist politics in South Korea.

NL and PD: Old and New

Differences between the NL and PD tendencies originated in the student movement of the mid-1980s. Prior to this, the movements were broadly united, and their ideological development and differentiation was only in its early stage. Broadly speaking, Marxism was a kind of consensus point, though implicit, because overwhelming anti-communist repression and National Security Law prevented young activists from any open discussion of Marxism.

However, after the Gwangju Uprising, a key watershed in South Korea’s democratisation, young students were politically and ideologically radicalised and the ideas of Leninism became more widespread. As a result, ideological and tactical debates slowly began to develop. One negative aspect of this ideological radicalisation was the overheated nature of political debates and subsequent mental fatigue of activists.

In this context, a small group initiated a propaganda campaign for KISism, or Juche Thought. Its revolutionary theory of National Liberation People’s Democracy Revolution (NLPDR) and its anti-imperialist, anti-US agitation appealed to many activists, leading to the birth of the NL tendency.

The NL tendency emphasised a mass line and flexible united front tactics, while pushing a simplified moral message with a nationalist tint. Its politics were attractive to young activists. Several pamphlets were enough to win over young activists who were tired of overheated debates. KISism came to be accepted as an alternative to Leninism, with informal underground leadership cells – a kin to a spy network – dominating the movement behind the scene while trying to connect with North Korea for ideological legitimacy.

The other Leninist tendency was broadly categorised as PD, emphasising the class struggle over a nationalist approach and anti-imperialist struggle. The PD tendency refused to recognise North Korea’s leadership, and rejected Juche Thought and the personality cult around the Kim family.

Unlike the NLs that put South Korean movements under North Korean leadership, PDs regarded South Korean movement as spontaneous and independent of North Korea. From the PD’s perspective, North Korea’s perception of South Korean society and its movement were backward and outmoded, and North Korea’s nationalist orientation represented a distortion of Marxism or Marxism-Leninism.

In 1991, NL groups initiated an organisational campaign to set up the National Coalition for Democracy and Nation Reunification (NCDNR, Jeonguk Yeonhap) as an attempt to establish a broader united front, but it essentially turned into a loose confederation of local NL groups.

In contrast, the PD tendency was not a single entity, but rather a loose network of dispersed groups. In competition with the NL tendency, with its mass campaign for national reunification and nationalist appeal, the PDs were a minority tendency.

The NLs were politically reformist, preferring to compromise in critical moments and ally with liberalism in its various forms. Seeking an alliance with the DP was a priority for NLs. On the other hand, the PD’s class-struggle approach abhorred political subordination to liberalism, even if tactical alliance were not completely ruled out in the democratisation phase of struggle.

Reformist PD groups dominated the DLP in its initial stages of formation, viewing it as following the German Social Democratic Party (SPD)-German Trade Union Federation (DGB) model of two wings of labour movement; that is, a political and industrial wing. Later, as NLs joined the party en masse, PD influence was reduced and reformist NL groups emerged as hegemonic within the party. NLs inside the DLP operated as a party within a party. Meanwhile more radical PD groups kept their distance from the DLP and its legalist approach.

The NL-PD dispute inside the DLP lost any revolutionary implication it might have once had. While political and organisational difference remained, they were not very meaningful and largely represented fights between two reformist wings.

| Parliamentary Election | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Party | Seats | Constituency | Party list | Votes | Percentage | Rank |

| 2000 | DLP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 223,261 | 1.2% | 5 |

| 2004 | DLP | 10 | 2 | 8 | 2,774,061 | 13.0% | 3 |

| 2008 | DLP | 5 | 2 | 3 | 973,445 | 5.68% | |

| NPP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 504,466 | 2.94% | 7 | |

| 2012 | UPP | 13 | 7 | 6 | 2,198,405 | 10.03% | 3 |

| NPP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 243,065 | 1.13% | 6 | |

| 2016 | JP | 6 | 2 | 4 | 1,719,891 | 7.23% | 4 |

| Green | 0 | 0 | 0 | 182,301 | 0.76% | 7 | |

| UPP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 145,624 | 0.61% | 8 | |

| LP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 91,705 | 0.38% | 10 | |

| 2020 | JP | 6 | 1 | 5 | 2,697,956 | 9.67% | 3 |

| PP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 295,612 | 1.05% | 7 | |

| Green | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34,272 | 0.21% | ||

| LP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34,272 | 0.12% | ||

Other Radical Left

The Labour Party has its origins in a split from the DLP in 2008. The anti-NL left refused to join the UPP and formed the NPP after Shim SJ and Roe HC left to join UPP. The NPP later renamed itself the Labour Party, though its base and link with trade unions and the working class more generally is rather weak or minimal. Former Socialist Party (SP) sect controlled the LP as a party within party. More recently, after the basic income campaign, this group left the LP and formed the Basic Income Party, which is essentially a satellite miniscule party of the ruling DP.

With no seats and no organisational strength, the LP essentially struggles for sheer survival. For now, it is a loose network of activists and party members who are not very active and the party is barely visible in national and local politics. Many rank-and-file party members were traumatised by the experience of internal disputes and splits.

On the other hand, there were a number of activists who were against the legalist DLP project, arguing that it was moderate in orientation and was gradually drifting toward the right. These groups emphasised popular struggle and workplace struggles instead of electoral politics. The Power of the Working Class (PWC), which was active between 1999-2010 was one of the key organisations in this trend. The PWC’s successor group is the PST, the Party for Social Transformation.

There are other radical left groups such as the Trotskyist, Stalinist and Left Communist grouplets. In general, these extra-parliamentary lefts are divided and fragmented, though committed to strikes and social campaigns. Furthermore, they have failed to build an alternative force, and sectarian grouplets are just instead focused on critique for critique’s sake.

Conclusion: Some Prospect

The KCTU was the backbone of progressive politics, but its moderation and various progressive parties’ internal disputes and splits led to the demoralisation of rank-and-file unionists and party members. Most of them lost interest in progressive politics, as well as hope in the possibility of a working-class party.

Some nostalgia for the early DLP days remains, but activists are reluctant to do politics or join a party. Though nominally each party kept members, political activities are minimal, and with the exception of JP – which has distanced itself further and further from the movements – no party has any chance of winning the next elections.

Recently, Han Sang-Gyun has announced his intention to run in the presidential election as a worker candidate. He was the militant leader of a 77-day-long strike at Ssangyong Motors in 2008, and was later elected KCTU president in 2015. As the first president elected by the rank and file in a direct ballot, he led the 2016 general strike and was jailed for 4 years.

Both the LP and PST welcomed Han SG’s mover. However, before his announcement, both parties had resolved to merge and build a new united party. They went down to the process of selecting an independent socialist candidate to run for the presidency. This is a positive move by the radical left, especially if Han SG and radical left candidate from LP-PST alliance could be unified.

However, the future is still uncertain and volatile for South Korea’s labour movement and progressive politics, just the past experience has shown. In spite of uncertainty and difficulties, the 2022 presidential election could be an opportunity for left unity and the revival of working-class and socialist politics, though a precise path forward is yet to be forged. •

A brief chronology of the left-wing parties

| 1995 | Founding of KCTU |

| 1997 | KCTU proposes to build a new party, PV21 was formed |

| 2000 | Founding of the DLP |

| 2004 | General election: DLP wins 10 seats |

| 2008 | 1st split: DLP vs NPP |

| General election: DLP wins 5 seats, NPP no seats | |

| 2011 | Founding of the UPP |

| 2nd split: UPP vs PJP/JP vs LP | |

| 2012 | General election: UPP wins 13 seats |

| 2014 | Dissolution of UPP |

| 2016 | General election: JP wins 6 seats |

| 2020 | General election: JP wins 6 seats |

Reference

- Kim Jang-Min, A Study on the Relationship between Left Party and Trade Union: On the Relationship between KDLP and KCTU, Gyeongsang University PhD Thesis, 2017.

- Kim Jang-Min, The Truth of the Case of the Dissolution of the United Progressive Party, Gongsanggongrack Publisher, 2017.

- Yunjong Kim, The Failure of Socialism in South Korea, 1945–2007, Routledge 2016.

- Won Young-Su, “Korea, Labour Movement, 20th Century,” pp 1981-1993, Immanuel Ness (ed), International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest, Blackwell Publishing, 2009.

This article first published on the Europe Solidaire website.