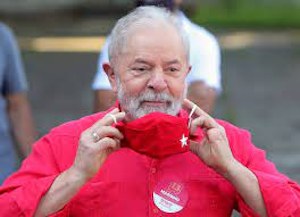

Brazil: The End of Bolsa Familia, Lula’s New Alliance, and Sergio Moro’s bid for the Presidency

At the end of October 2021, the Bolsa Familia social program made payments to Brazilians for the last time since being instituted during the first term of President Lula da Silva of the Workers Party (PT) in 2003. Despite its modest sum of R$200 (reals), about $35 (US) at today’s exchange rate, it became the best known social transfer program in the world, lifting millions of Brazilians out of dire poverty. It was however conditional, recipients had to prove that their children went to school and that household members got vaccinations, thereby incentivizing inclusion into the education and healthcare services.

The program, which became law in 2004, contributed decisively to two processes that were revolutionary for Brazil’s poor majority: millions of people received an identity card when they registered for the social program, and many more millions were able to get a bank account for the first time. Banks, even publicly-owned banks, in Brazil are not obliged to provide accounts to citizens – except where citizens can demonstrate sufficient need for one. The inclusion into Bolsa Familia was one such reason. This is why Bolsa Familia was such a groundbreaking change in Brazil.

Jair Bolsonaro Plan to Tax and Spend

In October 2021, the Bolsonaro government declared the program extinct and introduced a new program called Auxilio Brasil. The motivation was twofold. First, Bolsa Familia was associated with the Lula administrations, so Bolsonaro was eager to change its name. Second, he plans to pay R$400 per month instead of R$200. This is meant to boost his popularity among the poor. In November 2021, the new program started with a medium payment of R$223 per family for 13 million people, while the next installment in December 2021 will actually be a minimum of R$400 per family for roughly the same number of people. But the financial basis for the payment to go on at the same level in 2022 is not yet secure and depends on decisions in parliament yet to be made. Families with a per capita income of less than R$200 per month are eligible.

The tax reform, designed to generate new income by taxing dividends, planned by finance minister Paulo Guedes, did not pass Parliament in the summer. Guedes did not engage in negotiations with deputies before presenting the draft law which is a reflection of his lack of organic connections with the established political class. The planned tax on dividends was first reduced and then taken out of the draft in further negotiations, but the whole package of laws did not move further through the legislative process and is now effectively stuck. Another way to finance the new program would be to delay the payments that the federal state transfers to regional states. Instead of paying the sum at once, the Bolsonaro government aims to pay it across twenty years. The last proposal has already been approved in the Senate but still needs to go through Parliament.

Most importantly, the new program is not designed as a permanent social policy, but rather, is explicitly limited in duration to December 2022, immediately after the next presidential elections take place in October and November of 2022. This means that the fate of the poor in Brazil will be in the hands of whoever gets elected and takes the reins of government in January 2023. The fact that there have been no major protests against the dismantlement of Bolsa Familia speaks volumes about the current political apathy.

Limited Political Mobilization

On September 7, the day of Brazil’s national independence, Bolsonaro once again upended everything and announced an institutional rupture, trying to rally thousands of supporters for a testrun of a military coup. Despite bribe payments to supporters to come to rallies, the turnout was less than mediocre, and Bolsonaro apologized the next day – he said he had been carried away in his speeches.

Bolsonaro’s mobilization on Independence Day caused various opposition parties to plan major protests. However, after Bolsonaro apologized and read a letter that former president Michel Temer dictated to him, protests were either canceled or postponed. Apparently, a kind of truce between the traditional center-right and Bolsonaro was arranged with the help of Temer. Since then, Bolsonaro has kept some distance from the wildest firebrands of his grassroots base and avoided open confrontation with the Supreme Court, one of his favourite targets.

In the meantime, Bolsonaro’s government muddles through with a mishmash of policies, while his polling numbers for the first round of next year’s election are stuck around 25 percent, indicating the extent of his devoted support base.

In one of the last polls conducted by Ipespe, published on 26 November, Lula received 42 percent in the first round of elections. Last month, former Minister of Interior Sergio Moro, who left the Bolsonaro government in April 2020, announced that he would run with the center-right party Podemos. He now polls third, with 11 percent, followed by center-left candidate Ciro Gomes, with 9 percent.

In the second round of elections, polls indicate that Lula would win against Bolsonaro by 52 percent against Bolsonaro’s 32 percent. Interestingly, Bolsonaro would also lose against Sergio Moro and Ciro Gomes in the second round (although by a smaller margin), due to the 61 percent rejection rate of Bolsonaro as a candidate.

Disaggregation on the Political Right

The fact that Bolsonaro’s chances at reelection are poor is fueling the urge of the center-right to replace him in the second round of the elections. The traditional center-right Brazilian Social Democratic Party (PSDB) elected João Doria, governor of São Paulo state, as its candidate this past November. However, Doria is not very popular with the electorate, so it is probable that Sergio Moro will become the main candidate of the so-called third option. Aware of this fact, Doria already offered his cooperation to Moro one day after being elected candidate for his party.

This poses another problem for Bolsonaro because even if Moro can not earn more votes than Bolsonaro, Moro is catering to the same group of voters, and therefore will not take away many votes from Lula. In this way, the two main right-wing candidates will, instead, steal votes from each other rather than make any inroads into the potential voters of Lula.

Bolsonaro has been looking for a new party on whose ticket he could run in 2022, since he left his old Social Liberal Party (PSL) early in his mandate. He has been negotiating with half-a-dozen parties in the past few months in order to become their candidate but has been rejected several times.

He was finally able to join the rightwing Liberal Party (PL). The PL is at the moment the third-largest party in Parliament after the PT and Bolsonaro’s former party the PSL. It supports the Bolsonaro government, and was also part of the support base for the governments of Lula, Dilma Rousseff, and Michel Temer – thus, one of the classical clientelist parties that will join any government if it fits its interests. José Alencar, vice-president during Lula’s two terms, was a member of the PL during the first term, from 2002 to 2005.

Sérgio Moro is presenting himself as a lighter version of Bolsonaro, with a friendlier and more moderate outlook, and is collecting a large number of ex-Bolsonaro allies around him, most prominently General Santos Cruz, who was one of the first to part ways with Bolsonaro. But Moro does not have an attractive program, and it is questionable if he will have the charisma needed to win a presidential election.

Lula Prepares Allies and Agendas

Lula is, in the meantime, maintaining and even slightly increasing, his support in opinion polls. The large question looming is who will be his vice-presidential candidate. In mid-November, Geraldo Alckmin, who ran for the PSDB in 2018, was said to be in negotiations to become Lula’s vice-presidential candidate.

Alckmin is a representative of Brazilian industry and the traditional elite. Alckmin met with representatives of trade unions, like the second-biggest confederation Força Sindical, the União Geral dos Trabalhadores, linked with the center-right Social Democratic Party (PSD), Nova Central and Central dos Trabalhadores e Trabalhadoras do Brasil (linked to the left-wing Communist Party of Brazil (PcdoB), on November 29.

Sérgio Nobre, the president of the biggest trade union federation, Central Única dos Trabalhadores, underlined in a recent interview that he also approves of Alckmin as vice-president. On December 1, Lula confirmed the likelihood of this alliance for the first time. The debate around Alckmin running as vice-president with Lula shows that parts of the bourgeoisie and the center-left are ready to enter into a broad alliance to remove Bolsonaro.

In case Lula does eventually ally with Alckmin, such an alliance would eat into the voter base of Moro and Bolsonaro, making Lula appear much closer to the political center than with a co-runner from the center-left or left. Alckmin is set to leave the PDSB, as Lula signaled that an alliance with Alckmin would depend on which party he chooses as his new affiliation. It is highly probable that Alckmin will join the center-left Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB).

During his tour through various European capitals in November 2021, while Bolsonaro was on one of his few trips outside of Brazil in Dubai, Lula revealed a bit more about his future political orientation, putting the fight against inequality at the center and signaling, to the horror of the EU establishment, that he aims to renegotiate central parts of the EU-Mercosur trade agreement.

Lula intends to include rules that would incentivize industrial production in Brazil, instead of relegating the country to a supplier of raw materials, as it increasingly turned into before, during and after Lula’s presidencies. In distinction to Argentina, which is processing most of the soy produced in the country, Brazil is exporting much larger quantities of soy, the bulk of which is processed outside of Brazil, thus leaving the value-added processes to other countries.

Another issue on which Lula weighed in recently is his rejection of a limit on the state budget, which was approved by the Temer administration in December 2016 freezing all state expenditures for 20 years, and is a central instrument of the current round of neoliberal cuts in Brazil.

Lula promised, as well, to do away with the current pricing policy of the state-owned oil company Petrobras, which is transferring international prices to Brazilian consumers. He emphasized that 50 percent of the current rate of high inflation is due to state-sanctioned prices that can be undone. With the refusal of a ceiling on state expenditures and the price policy, Lula is aiming at two central facets of neoliberal rule, attracting both state-developmentalist circles and the popular masses.

Social and Environmental Questions

The social situation in Brazil is dire, and it is surprising that there are no large-scale protests. Inflation hovers around ten percent, and is much higher for basic goods like rice, beans, and gas for cooking. Gasoline and diesel prices shot up 40 percent in the last 12 months, so much so that many delivery and Uber drivers have left the business. The last payments of the Corona emergency transfers took place in November, and large parts of the population went hungry as a result.

Nevertheless, apart from the hope that Lula may change things when he becomes president in 2023, social movements or protests on a large scale are rare. The protests against Bolsonaro in May and June 2021 fizzled out, and the few strikes undertaken by delivery drivers, truckers in the biggest port of Santos, urban bus drivers and public servants in São Paulo, did not lead to the formation of a common front.

On the environmental front, illegal mining activities in the Amazonian states of Pará and Amazonas are at an all-time high, and indigenous populations who try to block illegal miners from advancing into remote areas face vicious attacks with machine guns. The police step in only when the scale of illegal mining operations is so large that they garner the attention of national television reports. However, most of these activities go unnoticed by the larger public. They are clearly financed by big capital, as can be seen by the presence of expensive construction equipment and automatic weapons brought into remote areas.

Much of this is gold mining, and the gold finds its way to larger commercial traders and established banks through forged documents. Recent research found that among the Munduruku nation in Pará, one of the largest indigenous nations, a majority have alarmingly high levels of quicksilver in their blood. Quicksilver is used for gold mining and remains in the rivers that provide the nations with drinking water and fish.

Any new government will have to start from scratch in many areas, and recent spotlights on Amazonia can also pose a danger since new strategies falling under the label of bioeconomy are being devised by politicians and companies.

A new trend among companies and large NGOs is to include traditional populations who live off their territories into global value chains, allegedly to increase their access to money and cut out intermediaries like traders. But this inclusion is seen as a dangerous precedent by social movements who represent those populations, as it would increase their dependency on big capital and set them into competition with each other, thus creating new divisions among traditional populations.

The social movements representing traditional and indigenous communities emphasize that their best guarantee of maintaining self-sufficiency and monetary income would be legal rights guaranteeing access to their territories, often under threat by commercial actors, and new state laws that strengthen the protection of those areas, and prevent illegal invasions by cattle ranchers, the timber industry, illegal miners and other groups with commercial interests. The access to land and the possibility of keeping this land free from environmental degradation remains a central battleground for rural Brazil.

Modest Improvements Possible

It is especially on the question of agrarian reform that the presidencies of Lula and Dilma Rousseff have been quite weak. Lula, at times, adopts the discourse around the so-called bioeconomy. The exact way in which a future government will approach the issue will be important. The concentration of landed property increased during Lula’s two terms, and a conflict with elites that profit from land grabbing will be risky for Lula if he wants to stay in power for a possible third term.

In sum, a government with Lula as president supported by the working classes might do away with some of the worst excesses of the neoliberal policies that were installed since 2016 and even gain support from sections of Brazilian capital exhausted by the economic and political turmoil of the Bolsonaro regime. However it is unclear if there will be any political opening for a more profound reorientation in the economic and political model. This will depend greatly on whether trade unions and social movements can regain some momentum and create demands that unite the different sectors of the oppressed.

The urban poor often have very different demands from the rural poor, due to different economic bases. Social policies for better access to cheaper prescription medicine, programs for better infrastructure and more funding and better standards for health, education and public transport will in any case benefit the large majority of the population. It might very well be in those areas that a new Lula government can at least reverse some of the trends of the past five years. •