Postal Banking: Public Banks that Do Not Only Serve the Rich!

On Wednesday, August 20, 2021, we caught up with Matt Corbeil and Geoff Bickerton, who both work in the Research Department of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW). Matt is a Research Specialist and represents the union on a joint committee with Canada Post that has been discussing expanding financial services at the post office. Geoff is the Research Director, and he has been involved in the campaign for postal banking for over a decade.

Thanks to the efforts of CUPW, Canada Post is launching a postal banking pilot project this fall in Alberta, Nova Scotia and in 14 Indigenous, remote and rural communities across the country. The postal bank will provide affordable services to low-income residents.

This interview is part of a series with the Blended Finance Project, a group of unions, non-governmental organizations, and academics who are concerned about the Canadian government’s embrace of what is called “blended finance.” We argue that blended finance is merely the latest iteration of the privatization and financialization of foreign aid, and we seek to promote more equitable public alternatives.

We decided to do an interview on postal banking for three reasons. First, in debates on financing for development, postal banks are an alternative to private, for-profit forms of blending since they can play a role in investing in communities. For example, in France and Vietnam, postal banks help to finance municipal services, including housing and education projects. Second, postal banks provide a pro-poor, pro-public form of financial inclusion. Third, postal banks can help us think about financial services as public services, just like other services that we associate with ‘public’ like health, education, water and electricity.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Adrian Murray (AM), Susan Spronk (SS): What is postal banking and what gaps does it address in the banking system?

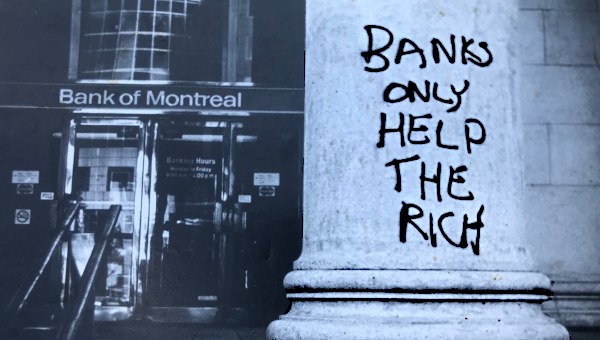

Matt Corbeil (MC): The idea of postal banking is actually quite simple. In most countries, Canada in particular, the post office network is the largest retail network throughout the country. It has contact points in every community. It’s also a public service with a mandate to serve the public good. The idea is to use this infrastructure to offer financial services, such as basic banking services to segments of the population who are excluded from the mainstream banking system. Private banks do not serve these customers because it’s just not profitable enough.

One of the ironies of mainstream banking is that the poorer you are, the more expensive it is to bank. The poor pay more. CUPW and other organizations feel that the post office can fill that gap and offer financial services at affordable prices that meet the needs of the underserved.

AM, SS: CUPW has been campaigning for postal banking for more than a decade. What changed recently to convince Canada Post to launch the pilot project this fall? Can you tell us about some of the turning points in the campaign?

Geoff Bickerton (GB): The management of Canada Post has shown an interest in postal banking ever since the Crown corporation was established in 1981. The first CEO and President, Michael Warren, would make speeches citing the fact that there are two thousand communities in Canada that had post offices and no banks. Subsequent presidents have voiced similar support for postal banking. But every time that they were going somewhere, and things looked positive there would be a change in government. The Tories would be elected, and things would stop, as most recently happened in May of 2011 [editors’ note: when Stephen Harper was elected].

Recently, the management has had to reevaluate its existing business model. In 2018, CUPW was finally able to achieve pay equity for the rural workers, which meant higher labor costs. These workers were underpaid by 30 percent, and they represent about 20 percent of the workers, so labor costs have increased. At the same time, letter volumes have declined, parcels have increased, but the latter is a much more competitive industry.

AM, SS: The current pilot project is in fact a partnership with Toronto Dominion Bank, which is a private, for-profit bank. What do you think would be required to create the independent public postal bank that would not require this kind of partnership? And what would the goal of an independent public postal bank be? Would it be to make profit? If so, where would that profit go?

MC: In our campaigns, CUPW has favored establishing an independent postal bank and we still do. If we go back to the research that we had commissioned, or some of the allies that we had worked with in the past – and I’m thinking in particular about a really great report that John Anderson did for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA). In that report, he shows there that there are different models that are effective including partnerships. In the United Kingdom, for example, the post office there has partnered with the Bank of Ireland, and it’s been successful. It has raised revenues for the post office, and it has expanded financial inclusion among the underserved in the United Kingdom.

AM, SS: Could you tell us a little bit about how a publicly-owned and operated postal bank might be different from a private, for-profit bank? For example, is it just about the price of banking services that we’re talking about here? Or is there something else that you think that this kind of model offers in terms of thinking about how to build a more sustainable future?

MC: The price of services is definitely a big, very big part of the story from our perspective. But let’s go back to basics. What is the purpose of a private bank? The purpose of a private bank is to maximize the return to its shareholders. It’s not to serve the public. So, you see that in a number of ways. You see that in the fact that private banks close down branches in areas that are not profitable, largely in rural communities – despite the fact that those branches are needed by the people who live there. Private banks don’t serve poor people. And that’s, in fact, why they have, you know, minimum balance requirements. If you do not meet the minimum balance requirement you have to pay big service fees, which is a disincentive designed push poor people out. Banks don’t offer small loans to low-income and moderate-income people because they don’t think that it’s profitable enough. So, by having a publicly-owned institution that has a mandate – a dual mandate – to finance itself and to serve the public, we think that we can fill that gap in the banking system.

The postal bank would focus on making a profit – to ensure the post’s self-sufficiency. There’s no sense in hiding that it is Canada Post, and it is important to clear up some common misconceptions about Canada Post. A lot of people think that Canada Post is subsidized by the federal government. It’s owned by the federal government. The federal government’s the single shareholder, but it’s not subsidized. So, Canada Post has a dual mandate. It must finance itself and it must meet some basic service obligations throughout the country. So, from our perspective, yes, Canada Post as a postal bank should be focused on making a profit, but it should do so in a way that’s fair to the people that it’s serving. And those profits should be reinvested in the corporation to expand services further.

GB: Having a postal bank with a public purpose will also make it easier for people to obtain unsecured loans to be able to start businesses. This is one of the major problems that people have in Canada, whether in rural areas, small towns but also in urban centers. If you don’t have any collateral, it’s very difficult to get an unsecured loan unless you go to a payday loan place and that’s got to change. This is definitely one of the first services that Canada Post is going to expand into.

AM, SS: Can you tell us a little bit more about the potential role that postal banks can play beyond retail services? More particularly, how can postal banks play a role in financing community development, for example, to address the problems of affordable housing?

GB: Let’s take a look at what happened in the banking crisis in 2007-2008 in France. Dexia Bank shut down in Europe. We all know what the banking system was doing, and the problems that it caused around the world. So, who stepped up to take care of the financing for public housing and municipalities in France? It was a large public sector bank and the postal bank, which formed a partnership.

So, in the 2021 election campaign the politicians are talking about creating massive numbers of new homes in the country. We need that desperately. We have a housing crisis. How best to finance that? From profit-making organizations like banks, who are going to try to maximize their profit? Or from an institution like Canada Post which according to the Act of Parliament that created says that its financial mandate is to be self-sufficient – not to make profits – but not to draw from the public purse, to be able to fund its own operations. So, if you have profits being made from the postal bank, where would they go? They should go for the public purpose. And this would be a bank that’s owned by the public.

Since 1993, there’s been a directive from the federal government the Canada Post cannot close rural post offices. If we were private sector bank there would be thousands of post offices that would have been closed. But again, making it public enables public influence and enables it to pursue public policy.

AM, SS: How can postal banking play a role in financing for development? Are there any examples of postal banks in the global South?

MC: Most of the literature on the global South on postal banking focuses on financial inclusion. There is very little research on these broader questions of investment and development. But one of the real stars, if you will, of postal banking in the global South would be Morocco, where over the course of a four-year period the postal bank was given a mandate to promote social inclusion, financial inclusion. The Al-Barid Bank (ABB) more than doubled the number of people who had a bank account. So, I think that the figures were like 34% at the beginning 62% after a four-year period. Hundreds of thousands of people got a bank account for the first time, so there was success at that level.

GB: The United Nations (UN) did a study on the impact of the creation of the postal bank in Brazil that has won many awards. The postal bank was created in 2002. Initially it involved a ten-year deal with a large private sector bank to assist it in its development. They opened thousands of branches in villages that had no banks whatsoever. According to the UN study, there was a positive impact in various regions of the country where there had been a significant expansion of financial services through the postal bank. It is a great example of where the presence of a bank has enabled the development of small enterprises and agricultural expansion, in terms of the actual output of the farms in the areas. Suddenly people could borrow money to buy equipment, etc. In addition to Morocco, there are other good examples from Uganda and Tanzania.

AM, SS: You have talked about middle-income countries. Could postal banking play a role, for example, in poverty alleviation and equitable financial inclusion in low-income countries?

MC: One of the problems – at least right now – is that in many of the lowest income countries the postal network is just not as developed as it is elsewhere. The Universal Postal Union, which is an agency of the United Nations, reports frequently on how well developed each country’s postal networks are. There are also studies about how developing strong postal networks also creates all sorts of positive externalities.

GB: It’s uneven, I think. There are some examples where postal networks have initiated telephone banking in some African countries. In the major cities you would see that there has been a greater integration of the postal banks and other services like telephone banking, etc., by working with the telecommunication companies. In the rural areas, as Matt said, the actual infrastructure is sorely lacking, so these are the very areas where one would hope that postal banking can really make a difference in terms of financial inclusion and economic development.

AM, SS: In mainstream international development circles, there’s a fascination with private sector-led financial inclusion mechanisms. This includes ‘Fintech’ (financial technology) such as mobile money and microfinance. Why is postal banking not capturing the public imagination in the same way, at least in the development community in Canada, given that there are so many great examples of postal banking around the world, including in lower income countries and middle-income countries?

MC: It is because the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is not funding research on postal banking! (Laughs.) But let’s maybe contextualize it. The problem is neoliberalism. The post office is a state-owned institution and according to neoliberal theory, state-owned institutions are ‘inefficient’; they just block out private sector, and that’s just bad, right? The problem is that for too long we’ve been living in a political context where the idea that a state institution can be innovative and that they can provide good services to the public is automatically rejected.

GB: Yes, I would distinguish between capturing the imagination and public support. There’s no great body of literature out there talking about how the world would change because of postal banking. However, a thousand municipalities in Canada have passed resolutions in favor of postal banking. The extensive polls that have been conducted, not only by Canada Post but by others, indicate that if all the people that said that they were definitely or very likely to sign up to a postal bank. If they did, the postal bank in Canada would be among the largest banks in the country! So, you know, when you actually ask people about it, there’s a lot of support and there’s a lot of recognition, especially because of the failure of the banks to serve the interest of a lot of people in Canada.

There is also a generational difference. Older people – in terms of the polling data – are well-established in their banking, and they’re not nearly as supportive. There is a great deal more support for postal banking amongst younger people. So, yeah, I don’t think it’s captured the imagination, but I think that if you drill down, you’ll find a very deep reservoir of support, one that we’re hoping to tap into.

AM, SS: Great! So, thanks very much. It sounds like this pilot project will provide some valuable lessons not only for development in our own communities across Turtle Island, but also in the global South. There’s a number of really exciting examples. Thank you so much for joining us with the Blended Finance Project. Best of luck! •