German Election: Losses for Establishment Parties, Defeat for Die Linke

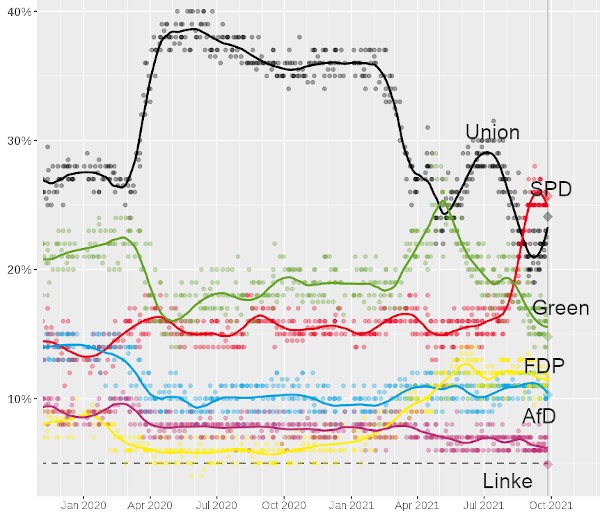

The parties in the “grand coalition” of Angela Merkel’s government, the conservative CDU/CSU (Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union) and the SPD (Social Democratic Party) attracted only a quarter of the electorate each. The CDU/CSU had its worst result ever with 24.1% of the vote. The SPD, with its candidate for Chancellor, Olaf Scholz, was able to regain ground (a few weeks ago, it had fallen below 15% in the polls), coming first with 25.7%.

So, 75% of the electorate will not have voted for the leading party in the next government, whoever it may be. The 1.6 million or so votes that the CDU/CSU lost to the SPD are also quite strongly linked to the conservative political profile of Olaf Scholz, a moderate from the generation of social democratic leaders who had fabricated the crude counter-reforms of agenda 2010.

With a turnout of 76% and 8.7% voting for the smaller parties that will not be represented in the Bundestag, the German parliament will only represent about a third of the electorate. The resulting loss of democratic legitimacy reflects a process that has been under way for years and is becoming increasingly pronounced.

Losers and Winners

On the far right of the parties in the Bundestag, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) cannot be satisfied with its losses, which bring it down to 10.3% and mean it has lost its rank as largest opposition party. In addition, it is torn by internal quarrels, some of its members and leaders wanting to support the Corona-deniers and march together with neo-Nazi formations and others showing a more serious attitude to the milieus of official bourgeois politics. Nevertheless, this party remains a formidable enemy which in many parts of eastern Germany has surpassed the CDU and has even become the strongest party.

The two winners are the Green party with 14.8% (a few weeks ago it had surpassed the CU/CSU and become the strongest party in the polls), its best result ever, and the liberal FDP (Free Democratic Party) with 11.5%, which is quite spectacular. Until further notice, no one is thinking of a revival of the “grand coalition” with the CDU/CSU as a junior partner of the SPD. What will be discussed and negotiated in the coming weeks (or months) are two options: either an SPD coalition with the Greens and the FDP, or the CDU/CSU with these same two parties, which will therefore play an important role in the next government. Even if it is not easy to imagine the compromises to be made (with the FDP being against more taxes on big incomes and wealth while wanting to prevent any new public debt, it is difficult to see how to finance the investments promised by the SPD and the Greens in infrastructure, renewable energy and electronic communications), as the CDU/CSU and its Chancellor candidate Armin Laschet are seen as the losers in the election, a “red-green-yellow” coalition may seem likely.

The Left

Die Linke, the “Left Party,” could not even reach the 5% of the proportional vote normally needed for representation in the Bundestag, with only 4.9% of the vote. However German electoral law also allows proportional representation to parties that win at least three local direct mandates and Die Linke did so (in Berlin constituencies). With this very bad result, Die Linke seems to have consumed all its credit acquired during its foundation. In 2009, it had won 11.9% of the vote, and this seemed to be a “good start.”

Who is to blame? Revolutionaries and the radical anti-capitalist left tend to attribute it to opportunism and adaptation to parliamentarism (which are real problems). With its participation in regional governments applying a fairly “normal” pro-capitalist policy, this party could no longer pass as a force of revolt against the rule of capital. But it’s not that simple.

The majority of people more or less ready to vote for Die Linke are rather inclined to desire the participation of this party in the government, even at the federal level, to achieve even a small part of its social and ecological demands. They even find the party’s positions against NATO (quite Platonic, in truth) and against any international intervention by the Bundeswehr (in this case, quite practical, because its deputies have always voted in accordance with this principle) a little too radical.

So, it’s not easy to find a recipe. It would not be honest to say that we would always know how we can win more votes. Sometimes you have to say unpopular things out loud, against the current. Or take the example of the 600,000 votes Die Linke lost to the SPD. It was a “useful vote” or “tactical vote” to prevent Armin Laschet from beating the SPD, which seemed possible in the very last days before the elections. Even in circles very close to us there were people who found it extremely difficult to choose: the risk that the CDU/CSU would win and the risk that Die Linke would not meet the 5% barrier both seemed real. And against a “useful vote” for the “lesser evil” in the broader milieus, it is not easy to invent a counter-poison.

That said, it is time to debate in Die Linke and in the left in general how, in the medium term, we can build a stronger political left, more rooted in the workplaces, in the neighbourhoods, in schools, active and inspiring in the social movements, the bearer of concrete mobilization and action projects that fit into a perspective of radical social change, to break the power of big capital and its political servants.

Because we can’t wait until 2025! The next government, if we only take into account the fight against the climate disaster, will be lost for another four years. And the window of time we have left is beginning to close. Either the victory of the principles of solidarity and ecological responsibility, or the end of all that has remained civilized on the planet.

The victory in Berlin, on the very day of the elections, of the popular initiative for the expropriation of big real estate companies (starting from 3,000 apartments) after a formidable campaign on the ground shows the way forward. •

This article first published on the International Viewpoint website.