Fossil Fuel and Meat Producing Countries Lobbying Against Climate Action

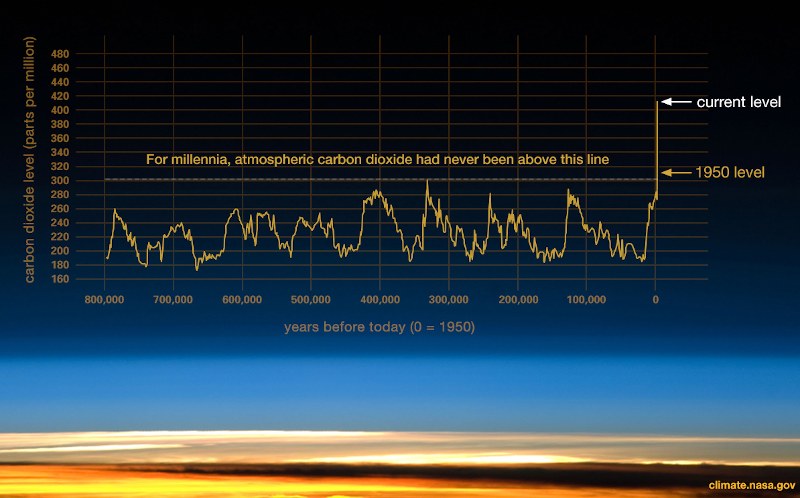

Some of the world’s biggest coal, oil, beef and animal feed-producing countries are attempting to strip a landmark UN climate report of findings that threaten those domestic economic interests, a major leak of documents seen by Unearthed has revealed. The revelations – which show how this small clutch of countries is attempting to water-down the International Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) major upcoming assessment of the world’s options for limiting global warming – come just days before the start of crucial international climate negotiations in Glasgow.

They come from a leak of tens of thousands of comments by governments, corporations, academics and others on the draft report of the IPCC’s “Working Group III” – an international team of experts that is assessing humanity’s remaining options for curbing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions or removing them from the atmosphere.

The documents passed to Unearthed show how fossil fuel producers including Australia, Saudi Arabia and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), are lobbying the IPCC – the world’s leading authority on climate change – to remove or weaken a key conclusion that the world needs to rapidly phase out fossil fuels.

In one comment seen by Unearthed, a senior Australian government official rejected the largely uncontroversial conclusion that one of the most important steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions was to phase out coal-fired power stations.

Meanwhile, Brazil and Argentina, two of the world’s biggest producers of beef and animal feed, have been pressing to delete messages about the climate benefits of promoting ‘plant-based’ diets and of curbing meat and dairy consumption.

COP26 Negotiations in Glasgow

The news comes just days before these countries take their places at the COP26 negotiations in Glasgow – a UN conference that has been described as the world’s “last best chance to get runaway climate change under control.” It is likely to raise questions about the threat posed to progress at the summit by some economies that remain highly dependent on carbon-intensive industries.

IPCC authors can and do reject suggested changes to their drafts if the comments are not supported by the scientific literature. However, the leak of these comments offers a unique insight into the positions being adopted by some countries away from the public eye.

Climate scientist Simon Lewis, professor of global change science at University College London, told Unearthed: “These comments show the tactics some countries are willing to adopt to obstruct and delay action to cut emissions… On the eve of the crucial COP26 talks there is, to me, a clear public interest in knowing what these governments are saying behind the scenes.” He added: “Like most scientists I’m uncomfortable with leaks of draft reports, as in an ideal world the scientists writing these reports should be able to do their job in peace. But we don’t live in an ideal world, and with emissions still increasing, the stakes couldn’t be higher.”

A spokesperson for the IPCC told Unearthed that the processes it used for preparing and drafting reports were “designed to guard against lobbying – from all quarters.” The main elements of this, he added, were “diverse and balanced author teams, a review process open to all, and decision-making on texts by consensus.” The Unearthed analysis of thousands of leaked comments submitted to the IPCC by national governments found that the majority of contributions were constructive comments aimed at improving the text.

Fossil Fuel Phase Out

The documents reviewed by Unearthed comprise swathes of peer review comments on the second draft of Working Group III’s contribution to the IPCC’s landmark Sixth Assessment Report. This group’s report – which is not due to be published until next year – will be a definitive assessment of the ways available to the world to limit global warming.

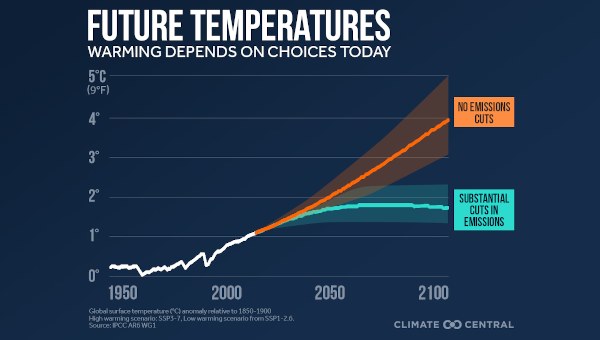

The executive summary of this draft – which was released in a separate leak earlier this year – details how global greenhouse gas emissions need to peak in the next four years. It states that, even if no new plants come on stream, existing coal- and gas-fired power stations on average need to close or be retrofitted to avoid emissions within the next 10 and 12 years respectively, if warming is to be limited to 1.5°C.

The leaked review comments – which consist of detailed responses to the draft by governments; businesses; civil society and academics submitted earlier this year – reveal how a small number of major fossil fuel producing and consuming countries reject the need for a rapid phase out of fossil fuels. Instead, this group argues, the IPCC must remain “technology neutral” and acknowledge the role that “carbon capture” technology could theoretically play in reducing the climate impact of fossil fuels.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) and carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS) are the names given to technologies that can capture carbon emissions from industrial sites like power plants, and keep them out of the atmosphere or use them in industrial processes.

Australia; Saudi Arabia; Iran, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC); and Japan all make variations of this argument, despite the fact that, according to the Global CCS Institute, there is currently only one power station in operation in the world that successfully captures some of its carbon emissions.

Analysis of public data shows that this power station, Boundary Dam in Canada, has missed its original target of capturing 90% of the carbon emissions from one of its generators and is now aiming to capture just 65%. The vast majority of global CCS capacity is, in fact, applied to natural gas processing rather than energy generation.

Speaking to Unearthed about the various pathways available for reducing carbon emissions, Siân Bradley, a Senior Research Fellow at Chatham House, told Unearthed: “CCS/CCUS is a critical technology, but there has never been any credible suggestion that it could deal with the bulk of fossil fuel related emissions as they stand today… Delivering the Paris Agreement,” Bradley continued, “requires the transformation of global energy and industrial systems, which means phasing out the vast majority of fossil fuel use and rapidly scaling CCS in ‘hard to abate’ sectors.”

Kingdom of Carbon

But by embracing this technology as a future bet, policy-makers can argue for a delay in action to limit fossil fuel use and justify new oil and gas fields coming on stream – regardless of whether CCS actually delivers. Chief among those pushing back against the recommendation that fossil fuels be urgently phased out of the energy sector are Saudi Arabia and OPEC, which together produce around 40% of the world’s oil.

Saudi Arabia repeatedly seeks to have the report’s authors delete references to the need to phase out fossil fuels, as well as an IPCC conclusion that there is an “need for urgent and accelerated mitigation actions at all scales.” In one comment, an advisor to Saudi Arabia’s Minister of Petroleum and Mineral Resources tells the authors to “omit” from the report a statement that the “focus of decarbonisation efforts in the energy systems sector needs to be on rapidly shifting to zero-carbon sources and actively phasing out all fossil fuels.” He claims that this sentence in the draft “undermines all carbon removals technologies such as CCU/CCS and limits the options for decision [sic] makers to carbon neutrality.”

Saudi Arabia even rejects the use of the word “transformation,” which the IPCC uses throughout the report to describe emissions reduction pathways that meet the goals of the Paris Agreement – the international treaty through which countries agreed to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, and preferably to 1.5°C.

For instance, the IPCC states in its draft Summary for Policymakers that scenarios “that limit warming to 2°C and 1.5°C imply energy system transformations over the coming decades. These involve substantial reductions in fossil fuel use, major investments in low-carbon energy forms, switching to low-carbon energy carriers, and energy efficiency and conservation efforts.”

Instead Saudi Arabia argues that urgent action to tackle the climate crisis is not necessarily needed: “The use of ‘transformation’ should be avoided as it has policy implications by requiring immediate policy actions. Transitioning to low-carbon economies can be achieved through planned interventions and by considering various transitioning options.”

In another comment, the Kingdom’s ministry of petroleum advisor claims that “phrases like ‘the need for urgent and accelerated mitigation actions at all scales…’ should be eliminated from the report.”

New Technologies

Saudi Arabia’s preferred approach to tackling climate change involves relying on as-yet unproven technologies which could enable nations to continue burning fossil fuels by sucking the resulting emissions out of the atmosphere – a concept it packages as the “Circular Carbon Economy.”

In line with this strategy it complains that the IPCC does not give sufficient attention to the feasibility of direct air capture (DAC), a technology in the early stages of development that is intended to draw carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere to be stored or used in industrial processes.

Relying on the development of technologies like DAC and CCS would allow nations to emit more greenhouse gases now on the optimistic assumption that they could draw them out of the atmosphere later, opening up the possibility of bringing temperatures back to within the limits agreed in the Paris Accord.

In one comment, responding to a section of the IPCC report discussing the “accelerated decarbonisation of electricity through renewable energy,” Saudi Arabia complains that the IPCC is “excluding natural gas and clean fossil fuel technologies e.g. CCUS and DAC from the decarbonization electricity generation Net Zero models.”

The reviewer also complains that CCUS and DAC technologies are excluded from a list of lower carbon emissions fuels, which includes renewables, bioenergy and “non-fossil” fuels that will be necessary to accelerate climate change mitigation.

But according to Professor Robert Howarth of Cornell University, there is no scientific evidence that humanity can rely on carbon capture or direct air capture in this way. “There’s no objective information out there which would suggest that this is a well proven, functioning, affordable technology,” he told Unearthed. “All the information is to the contrary… Clearly if a nation has huge reserves of fossil fuels they may feel some national interest to protect that interest and try to encourage the world to use them. But that’s not in the global interest, you’d hope that countries would have a broader perspective than that.”

While the IPCC report does outline how direct air capture and CCS could play a role in the future, it also says there is uncertainty about the feasibility of these technologies.

Saudi Arabia takes issue with this, rejecting analysis that “CCS may be needed to mitigate emissions from the remaining fossil fuels that cannot be decarbonised, but the economic feasibility of deployment is not yet clear.”

The Saudi government reviewer writes: “The CCS technology is now [considered a] viable option and its feasibility should be considered by the authors in all the chapter[s].”

Discussing the risks posed by emissions reduction pathways involving technologies that are not yet fully developed, Siân Bradley of Chatham House told Unearthed: “over-reliance on CCS and negative emissions technologies, should they fail to materialize, would lock-in a high-emissions pathway with no obvious escape route. The risks here cannot be overstated.”

On transport, the Saudi reviewer also appears to suggest a continued role for petrol and diesel vehicles: “claiming that the electrification of transportation, hydrogen, and biofuel are the only way to decarbonize the sector while totally exclude [sic] the ICEs [internal combustion engines] from the scene. Other options should be included.”

Unburnable Oil

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) – which represents 13 major oil producing nations including Saudi Arabia – shares the Saudi enthusiasm for removing references to a fossil fuel phase-out from the report.

In the comments reviewed by Unearthed, it tells authors to delete the sentence “More efforts are required to actively phase out all fossil fuels in the energy sector, rather than relying on fuel switching alone.” OPEC claims this “is not a policy-neutral statement considering, for example, that technological advancement could play a key role” in cutting emissions.

Similarly, it asks authors to delete the conclusion: “If warming is to be restricted to 2°C, about 30% of oil, 50% of gas, and 80% of coal reserves will remain unburnable.”

Duncan McClaren, a Research Fellow at Lancaster Environment Centre, told Unearthed: “In resisting a rapid fossil fuel phase out in favour of such technologies of prevarication, these countries are effectively saying humanity can run down the remaining carbon budget more quickly. But this would leave us in a hugely difficult situation in the future, having to deliver on large amounts of carbon removal regardless of the costs and impacts involved.”

“Sadly, this sort of promise of a future technology actually works best for the fossil industry if in practice it’s too expensive to implement,” McClaren continued, “because they can go on making promises, but never actually have to spend money to do it.”

OPEC also asks the authors to strike out a number of references to fossil fuel lobbies impeding action on climate change including the sentence: “Several scholars have traced delay and sluggishness by states to pursue [ambitious] climate mitigation policies to the activities of powerful interest groups who have vested interest in maintaining the current high carbon economic structures.”

OPEC member Iran, meanwhile, separately comments that limiting global warming to 1.5°C is not possible and the world should aim for 2°C: “Given current trends and technologies, a continuous annual reduction in greenhouse emissions of more than 5% between 2021 and 2030 is highly unlikely. Even developed countries have not been able to continuously reduce emissions to this level yet. Therefore, it seems that the goal of limiting the temperature increase to 2 degrees should be pursued instead of the 1.5 degrees goal (As agreed in the Paris Agreement).”

Meatless Mondays

Elsewhere, the documents reveal an escalating dispute over the role of animal agriculture in driving climate change.

Government officials from Brazil and Argentina – both countries with influential agribusiness lobbies that are among the world’s biggest producers of beef and animal feed crops like soyabeans – push repeatedly for the IPCC to remove or water-down messages in the report about the need to curb meat and dairy consumption to tackle global warming.

In comments on the draft seen by Unearthed, both countries call on the authors to delete passages in the text which suggest a shift to plant-based diets would cut greenhouse gas emissions, or which describe beef as a “high carbon” food.

In addition, Argentina presses for a swathe of further deletions – including references to taxes on red meat and even to the international ‘Meatless Monday’ campaign, which encourages people to go vegetarian one day a week – on grounds that these are “biased concepts.”

In the half-decade since the Paris Agreement came into force, the impact of animal agriculture on the climate has come under rising scrutiny, and a series of influential reports have argued for a shift to plant-based protein.

A 2018 study published in the journal Science, which examined data from 38,700 farms across 119 countries, found that moving “from current diets to a diet that excludes animal products” could cut food’s land use by around 3.1 billion hectares and its carbon emissions by 49%.

Modelling for the study found that, in addition to the direct cuts to farming’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the land freed by this change could remove around 8.1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere each year over 100 years, through the regrowth of natural vegetation and soil carbon stores.

Joseph Poore, the Oxford University academic who led the research, concluded that a “vegan diet is probably the single biggest way to reduce your impact on planet Earth.”

Greatest Impact

The following year, the IPCC itself published a 900-page special report on climate change and land, which found that the “extensive literature on the relationship between food products and emissions” consistently identified meat, particularly beef, “as the single food with the greatest impact on the environment.” As one example, it cited a study that found beef made up 4% of the weight of food sold in the USA but accounted for 36% of the food-related emissions.

“We don’t want to tell people what to eat,” IPCC adaptation working group co-chair Hans-Otto Pörtner said when the report was released. “But it would indeed be beneficial, for both climate and human health, if people in many rich countries consumed less meat, and if politics would create appropriate incentives to that effect.”

Despite this burgeoning literature, Brazil – where agriculture-linked Amazon deforestation is rising sharply under agribusiness-friendly President Jair Bolsonaro – has tried to prevent the IPCC making direct links between meat consumption and global warming in its landmark mitigation report.

For example, in comments recorded in March this year, the Brazilian foreign ministry seeks to remove wording from the draft which states that a shift to diets with a higher share of “plant-based protein” in regions where people eat an excess of calories and animal-based foods could lead to substantial reductions in GHG emissions and provide health benefits.

Brazil further asks for the full deletion of sentences from the same section which read: “Diets low in meat and dairy are already prevalent in many countries and cultures and their take-up is increasing from current low levels elsewhere. Plant-based diets can reduce GHG emissions by up to 50% compared to the average emission intensive Western diet.”

As justification for these proposed deletions, the Brazilian reviewer writes: “It cannot be assumed that plant-based diets and healthy diet are the same, that both will have a low environmental impact or that a sustainable diet will be healthy.” Sustainability, he claims, “depends on the local reality” which is influenced by local soil and climate conditions and “therefore, by the agricultural aptitude of the region” producing the food.

Rodrigo Rodriguez Tornquist, Argentina’s secretary for climate change, sustainable development and innovation, also calls for the wholesale deletion of this paragraph from the report, claiming that there is “no scientific basis for such affirmation on plant based protein diets” and no “multilateral consensus on such ideas” at the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN.

No Evidence

But his approach is more systematic than his Brazilian counterpart’s, finding dozens of other places in the report where he wants the authors to delete or water-down statements about the impact of meat on climate change.

Rodriguez Tornquist repeatedly asks for the idea of “sustainable” diets to be deleted from the report; likewise, he repeatedly asks for the deletion of references to plant-based diets and to taxes on red meat or taxes on “food with high GHG intensities” claiming that there is no “sound scientific evidence” that these measures would reduce emissions, or simply that their inclusion is “biased.”

On one occasion, he even pushes for the authors to tone down language stating in general that the use of antibiotics in livestock production poses health risks linked to antimicrobial resistance, insisting that “this is not the case if [antibiotics are] used in accordance with multilateral science-based [recommendations].”

Argentina’s requested deletions generally rested on claims that “shifting diets toward a more vegetarian balance do not guarantee a reduction in GHG emissions”; that generalisations about meat or beef being high-carbon are inappropriate because “not all meat production systems play a detrimental role in terms of GHG emissions”; and that grazing lands “can have a positive impact in terms of carbon sequestration” – a claim which is disputed.

Brazil and Argentina were not the only commenters to express scepticism about the draft report’s conclusions on meat and dietary change, although they were the only such meat-producing countries that Unearthed found to repeatedly insist on the deletion of these statements.

By contrast, Argentina’s close neighbour Uruguay comments on the Summary for Policymakers: “There are extensive and natural livestock production systems in countries such as Uruguay, which imply important co-benefits in terms of biodiversity, soil quality, water quality, as well as significant synergies between mitigation and adaptation that should be recognized at the international level. Not all the production systems are the same and these differences should be noted in these type of documents, trying to avoid generalizing these aspects.”

Coal Exports

Comments designed to weaken key elements of the report were also made by developed countries. Australia, one of the world’s largest exporters of coal and gas, shared Saudi Arabia’s rejection of the IPCC’s analysis that fossil fuels urgently need to be phased out of the world’s energy systems.

In a section of the report titled “What are the most important steps to decarbonise the energy system?” the IPCC says that near-term action must be taken to phase out coal- and gas-fired power stations, while deploying low- and zero-carbon electricity sources. Longer-term, the IPCC adds, less-developed technological fixes, such as hydrogen fuels and fossil fuel power stations equipped with carbon capture, should be tested and improved upon.

Phasing out fossil fuel power in the near term should, it says, be “accompanied by efforts to improve and test out options that will be important later on, including hydrogen or biofuels in cars and trucks, and fossil power plants, bioenergy power plants or refineries with CCUS [carbon capture utilisation and storage].”

Australia rejects this analysis, suggesting that carbon capture can be deployed in the near-term to avoid phasing out coal and gas power.

A senior official at Australia’s Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources says: “These remarks confuse the objective (eliminating emissions) with the means ‘retiring existing coal-fired power’. CCUS remains relevant to zero emissions.”

In another comment, the government official suggests Australia be deleted from a list of the world’s major producers and consumers of coal – despite Australia being the fifth largest coal producer in the world between 2018-21 – on the grounds that it does not consume as much coal as other countries.

Elsewhere, Australia asks the IPCC to delete analysis explaining how lobbying by fossil fuel companies has weakened action on climate change in Australia and the US: “One factor limiting the ambition of climate policy has been the ability of incumbent industries to shape government action on climate change (Newell and Paterson 1998; Breetz et al. 2018; Jones and Levy 2009; Geels 2014). Campaigns by oil and coal companies against climate action in the US and Australia are perhaps the most well-known and largely successful of these (Brulle et al. 2020; Stokes 2020; Mildenberger 2020).”

Despite the large number of academic references the IPCC draws upon in making the statement, the Australian government official requests “deleting this political viewpoint made to seem factual.”

Coal Imports

One major recipient of Australian coal exports, Japan, also pushes back against the conclusion that fossil fuel power stations need to be phased out.

Japan, which is hugely reliant on fossil fuels in its energy and transport systems, rejects a key finding in the report’s summary for policymakers detailing how coal and gas fired power stations will, on average, need to be shut down within 9 and 12 years respectively to keep warming below 1.5°C and 16 and 17 years to keep warming below 2°C.

A director in Japan’s ministry of foreign affairs claims this paragraph is misleading and suggests deleting it “because the required retirements of fossil fuel power plants due to carbon budget depend on the emissions from other sectors as well as their capacity factor and the opportunities of CCS.”

Japan also rejects analysis that “the overall potential for CCS and CCU to contribute to mitigation in the electricity sector is now considered lower than was previously thought due to the increased uptake of renewables in preference to fossil fuel.” The official argues that “it would be better to remove this sentence to be more policy neutral.”

Unearthed approached Saudi Arabia, OPEC, Australia, Brazil, Argentina, and Japan for comment on this story.

A spokesperson for the IPCC told Unearthed: “Our processes are designed to guard against lobbying – from all quarters – there’s more on this further below. The main elements are diverse and balanced author teams, a review process open to all, and decision-making on texts by consensus… This IPCC process is fully transparent, and we routinely publish the preliminary drafts, the review comments and the author responses to the comments, once the report is finalized.”

He added: “The drafts of the report are just that – early versions of the report where the authors test out their ideas with each other and then revise them in line with discussions within the IPCC and in the light of the review comments formally received in the IPCC review process and of the continued reading of the scientific literature… That is why we keep them confidential during the preparation of the reports, so that the authors have the time and space to try out and develop their thinking on the assessment. The early drafts are not IPCC reports and should not be considered as such. For that reason we do not get into discussions on the contents of the drafts.” •

This article first published on the Unearthed website, Greenpeace UK’s journalism project.