Is Turkey’s MHP Really Against Military Coups?

Turkey’s history is littered with military coups and memorandums. Even when there is little danger of a coup, there is the continual propagating of the idea that a coup remains an imminent possibility. Turkey is again drowning in a military coup debate over the last days with the tumult about another alliance between the Justice and Development Party (AKP) – which was born of military coups made against the left – and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), whose history includes preparing the ground for military coups. It was the published declaration of 104 opposing retired admirals, who are against making the Montreux Straits Convention1 open for discussion, that started the debate.

Right after the declaration was published on April 4 this year, AKP and MHP officials made statements targeting the retired admirals The detainment of the admirals who signed it and abolishing their housing and protection rights quickly ensued. Ten of the admirals were detained on April 5. Four admirals, over 70 years old, were summoned to the police headquarters to testify. The housing and protection rights of the admirals, who signed on the same day, were abolished. The detention period was extended for 4 more days on April 8. Fourteen admirals were released under judicial control provisions. On April 16, seven more admirals were called to the police station to testify. These processes are expected to continue.

It was the MHP and its leader, Devlet Bahçeli, who targeted the retired admirals (having earlier targeted journalists, university students, women, LGBTI+ individuals, Kurds, and socialists) and causing them to be subjected to violence. On the day the declaration was published, Bahçeli made the following statements on both his party’s website and his social media account:

“The anti-democratic and threatening and also authoritarian declaration signed jointly by 103 retired admirals is condemned by the Nationalist Movement Party and rejected. (…) the background and history of the declaration must be thoroughly investigated, and those involved in this disgrace must be identified. The issue is our homeland, our democracy, and our national will. The cost of compromise or delay will undoubtedly be heavy.” (Emphasis added in italics here and other quotes below.)

Upon reading this statement, anyone unfamiliar with Turkish history might think that the MHP is against military coups. But is that really the case? Is the MHP against military coups and authoritarianism? On the contrary, the MHP has always been intertwined with coups, sometimes acting as the spokesperson and instigator of coups, and sometimes the organizer of terrorist acts preparing the ground for military coups. This role of the MHP can be illustrated with a few historical examples.

May 27, 1960: Türkeş: The Mighty Colonel of Coup d’Etat

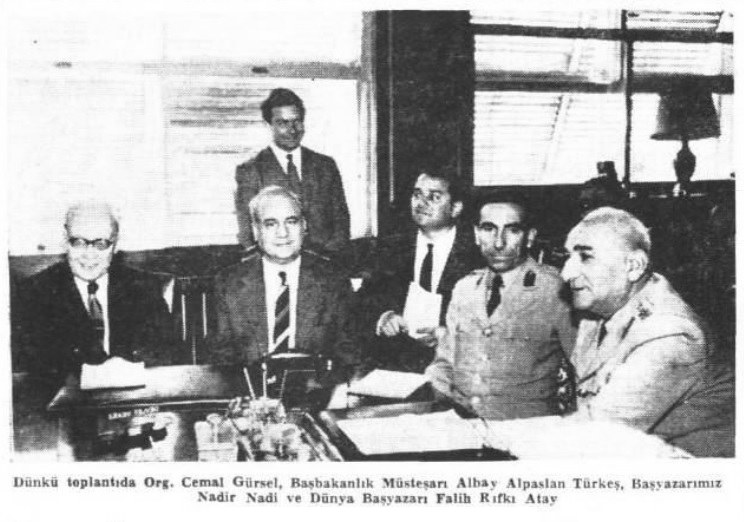

As is known, the first military coup in Turkey’s history was carried out on 27 May 1960 against the Democratic Party in power at the time. Alparslan Türkeş, who will form the MHP in the future, was among the soldiers who were members of National Unity Committee (MBK). Türkeş became the Prime Ministry Counselor right after the coup and was known as the “mighty colonel” due to the powers he usurped. He is also the person who read the coup declaration on the radio:

“Today, due to the depression our democracy has fallen into and the recent sad events, in order not to reduce infighting the Turkish Armed Forces has taken over the administration of the country. Our Armed Forces started this operation to save the parties from the uncompromising position they fell in and to allow fair and free elections as soon as possible under the supervision and arbitration of a non-partisan neutral administration, and to hand over and transfer power to the winners of the election regardless of which side they belong to.”

According to Türkeş’s statements, the coup that was made to “save democracy and put an end to the fight between brothers” would not remain in office for long, but would transfer the administration to the winning political party after “having fair and free elections as soon as possible.”

However, the first person to break this rule promised on the radio would be Alparslan Türkeş himself, once again. Advocating for the military administration to remain in power for an extended period of time, Türkeş and thirteen soldiers (referred to as ‘14s’ in history) ended up being ousted from the MBK on 13 November 1960 and sent on missions abroad – not to return to the country for at least two years.2 Cemal Gürsel, the Turkish president at the time, summarized the reason for this saying, “We promised to bring democratic order to the nation; this promise will be kept.”3

May 21, 1963: Türkeş is Excluded from the Coup Attempt

Returning from exile in March 1963, Türkeş immediately got involved in another military coup attempt. But Turkeş’s intentions for staging a military coup and assuming its leadership started before coming to Turkey. According to the file on those responsible for the coup that who would stand trial in a short time, some of the ‘14s’ that were liquidated from the MBK were in contact with each other:

“After the army seized power on May 27, some important members of the MBK were trying to enter the democratic order as soon as possible in accordance with their promises, but fourteen of them were liquidated from MBK for expressing their desire to remain in power without elections on 13 November 1960. It was even announced in newspapers that the 14s, who had been appointed as foreign advisors for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, contacted each other abroad. Indeed, at the meeting in Brussels of the 14, the strategies they would follow after returning to Turkey were negotiated, but Orhan Kabibay and Alparslan Türkeş did not agree on leadership issues.”4

Türkeş’s desire for the coup and leadership continued even after he returned to the country. The fact that there was an ongoing coup preparation was exactly the opportunity he was looking for. For this reason, he met with Colonel Talat Aydemir, who was the head of the coup preparations. Cumhuriyet Newspaper reported this relationship from the case file, as follows:

“After returning to Turkey, Türkeş was welcomed with ceremony like Kabibay before him by Fethi Gürcan, Bahtiyar Yalta, and Mustafa Ok, and appointments were made for Talat Aydemir. After Aydemir’s first courtesy visit with Türkeş, on his second visit he rejected the draft negotiations on the main issues and the fact that they could not reach an agreement on leadership was made known to those at Talat Aydemir’s house on 3 March 1963.”5

According to Uğur Mumcu, who was murdered on 24 January 1993, Türkeş denounced the coup attempt after failing to be given the lead: “Alparslan Türkeş, after returning to Turkey in 1963, because he informed the government about the military coup attempt under Talat Aydemir’s leadership, was released after a short period in prison.”6

Zihni Çetiner, who was arrested and sentenced to prison for taking part in the coup attempt of 21 May 1963 and who was one of the youth leaders of the ‘68 Generation, stated after being released from prison that the day and time of the coup was revealed by Türkeş, and that this was entered into the court minutes:

“Talat Aydemir and Alparslan Türkeş joined forces and their paths parted during the meeting they held in Dikmen to plan the revolution together. Although it is not entirely clear, Türkeş’s insistence on the leadership is shown as the reason. It is well known that Türkeş’s discourses on legal politics and democracy are just verbiage. The main issue is the leadership. At the aforementioned meeting, Aydemir did not give up the leadership to Türkeş. After the February 22 uprising, several young lieutenants were in contact with both Aydemir and Türkeş. The side that these young officers favored was that of Türkeş. Acar Okan, one of these lieutenants, learned the day and time of the May 21, 1963 revolution attempt. He immediately found a way to transmit this information to Türkeş. Türkeş then notified Fuat Uluç from CKMP (Republican Peasants Nation Party). This person told CKMP MP İsmail Hakkı Yılanoğlu. He informed Hasan Dinçer, the Minister of Justice of the same party in the coalition government. The Minister conveyed the information to Prime Minister İsmet Pasha.”7

As a result, the coup failed, and the two commanders of the coup (Talat Aydemir and Fethi Gürcan) were executed. Despite reporting the coup, Türkeş was imprisoned for four months.8

March 12, 1971: Passive Supporter of the coup d’etat, Chieftain

Türkeş, who was released four months after being arrested for taking part in the coup attempt of 21 May 1963, started organizing activities through the “civilian” party. On March 31, 1965, he joined Republican Peasant Nation Party and became the chairman in the same year. At the congress held on 8-9 February 1969, he changed the name of the party to the Nationalist Movement Party. The party emblem became three crescents and the emblem of the youth organization a gray wolf. Similar to Musollini’s Duce, and Hitler’s Fuhrer titles, he declared himself Chieftain.

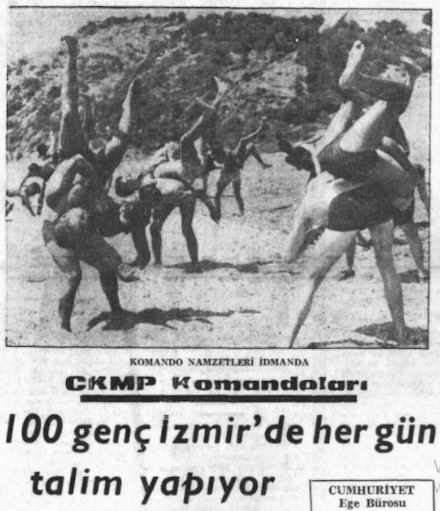

Başbuğ’s first action was to open commando camps where nationalist youth who would fight against communism would receive ideological and military training. From 1969 to 1980 – under the control of Dündar Taşer, a close friend Basbuğ made during the military coups of May 27, 1960 and May 21, 1963 – young people, who were raised in camps where thousands of Grey Wolves were educated, were not only a striking force against the danger of communism, but they also undertook the mission of “helping the military and the police.” However, the military intervention of March 12, 1971, put an end to this arrangement.

Türkeş particularly avoided commenting on March 12. He avoided journalists’ questions. He also did not participate in the vote of confidence for the new government created by the putschists.9 Finally, in the vote of confidence on June 5, 1972, he supported the March 12 government.10 The MHP, which did not need to hide anymore that it was on the side of the coup plotters, said in its election declaration published in 1973 that “the Grey Wolves transferred their duty to the honorable armed forces with the March 12 memorandum.”11

On the way to the September 12, 1980 Coup, the support given to the March 12, 1971 Coup became clearer. Former MIT member and Germany’s MHP Chief Inspector Enver Altaylı wrote on March 14, 1980, in Hergün, the MHP daily newspaper of, where he was the editor-in-chief, as follows: “We condemn those who curse March 12th again.”12

September 12, 1980: The coup Preparer MHP

After the lifting of martial law and political pardon of 1974, Turkey’s revolutionary forces and social opposition enter short boom episode. The MHP, whose fundamental purpose and only struggle was to suppress this, organized terrorist acts and endeavored to carry out a right-wing coup. For this aim, on March 12, they tried to bring MHP member General Namik Kemal Ersun, who also served as the Ankara Martial Law Commander, to head the army. Ersun, who also served as the Secretary General of the National Security Council (NSC) for a period, was appointed as Commander of the Land Forces on March 29, 1976 after the decree was put into effect without being published in the official newspaper. However, Türkeş’s dream did not succeed. Namik Kemal Ersun of the MHP, who was to become the Chief of General Staff for the next term according to custom, retired, on the pretext of his health status, on June 1, 1977.

Describing Ersun as a “harsh and ruthless soldier”, Uğur Mumcu writes about this dubious retirement process:

“It is said that Ersun has been attempting a revolution in recent months and maintaining relations with Türkeş. If this is the case, Ersun should be brought before the court without any delay. No, if these are empty rumors, then, isn’t it obligatory for the General Staff to announce to the public the reasons for retirement?”13

Ersun won the lawsuit filed with a request for the cancellation of the retirement process and requested a return to the post. However, Kenan Evren, who was the Commander of the Land Forces at that time, was appointed as the Chief of General Staff on March 6, 1978. Thus, the dreams of Türkeş and Ersun of “having a commander from the MHP” did not come true. The Namık Kemal Ersun incident would be told years later in Miyase Ilknur’s article series titled “Counter-guerrilla at Work” published in Cumhuriyet Newspaper last year:

“Namık Kemal Ersun had attempted to prepare a coup in order to prevent the CHP from coming to power. Ersun, who frequently went to Istanbul for planning the coup attempt, was meeting with the generals and officers from the Special Warfare Department. Ersun and his team were behind the preparations for the May 1 massacre, the assassination of Ecevit at Taksim rally, and the Çiğli assassination. Ersun’s team was liquidated by the Supreme Military Council, which convened two months later. Recai Engin, the former head of Special Warfare, and Lieutenant General Musa Öğün were among the 850 officers expelled from the army.”14

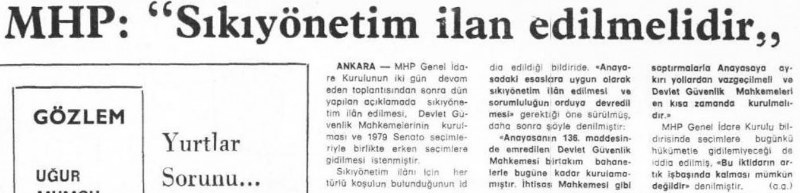

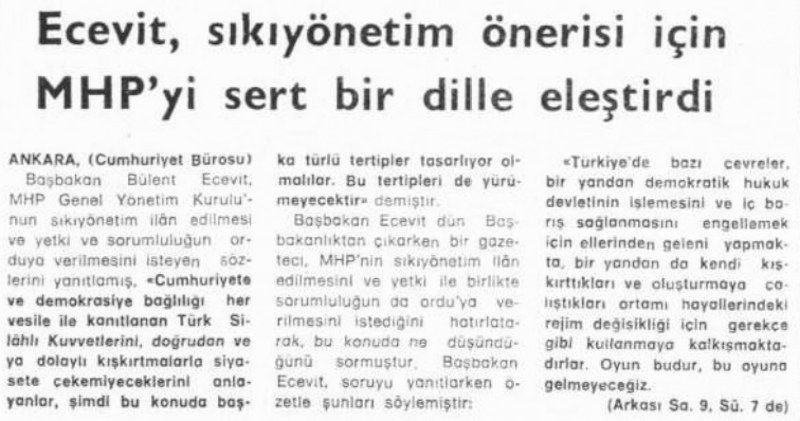

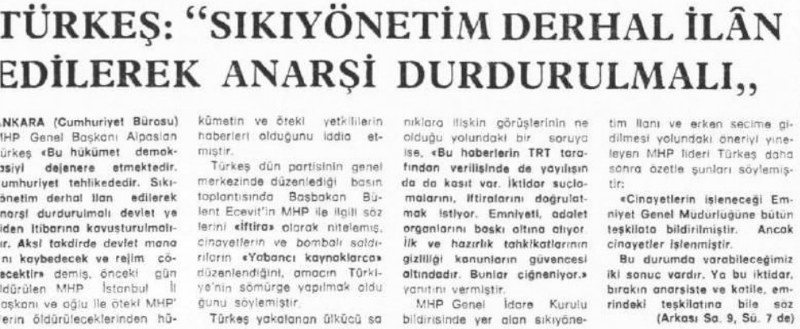

Türkeş put the plan of “forcing a coup from outside” into practice, when his plans of “making a coup from within” failed. He developed a new strategy upon the collapse of Nationalist Front government, which included him, and established a CHP government under the prime ministry of Bülent Ecevit. After a two-day meeting, the MHP demanded a declaration of martial law to establish State Security Courts – martial law courts – and early elections on October 2, 1978.15 According to MHP, “Martial law must be declared in accordance with the principles in the Constitution, and the responsibility must be transferred to the army.” Bulent Ecevit, the prime minister of the CHP, responded to the MHP’s call, and made the following assessment, as if predicting what would happen shortly: “Those who understand that they cannot engage the Turkish Armed Forces in politics through direct or indirect provocations must now be designing different arrangements on this issue.”16 Responding to these words the next day, Türkeş accused the Ecevit government of “degenerating democracy” and repeated the call “that martial law must be declared immediately.17

Interestingly enough, shortly after Türkeş’s call for the declaration of martial law, affirmation of Ecevit’s statement “they must be designing other kinds of schemes” came from Maraş between 20 and 24 December 1978. MHP and Grey Wolves fascists carried out a brutal massacre that lasted for days, killing 111 people, according to official figures. The CHP government of the period, which did nothing to prevent the Maraş Massacre, declared martial law covering thirteen provinces right after the massacre, opening the way to military rule. Türkeş got what he wanted. However, the declaration of martial law was not enough for Türkeş: “The government should allow and not intervene in the practices of martial law.”18

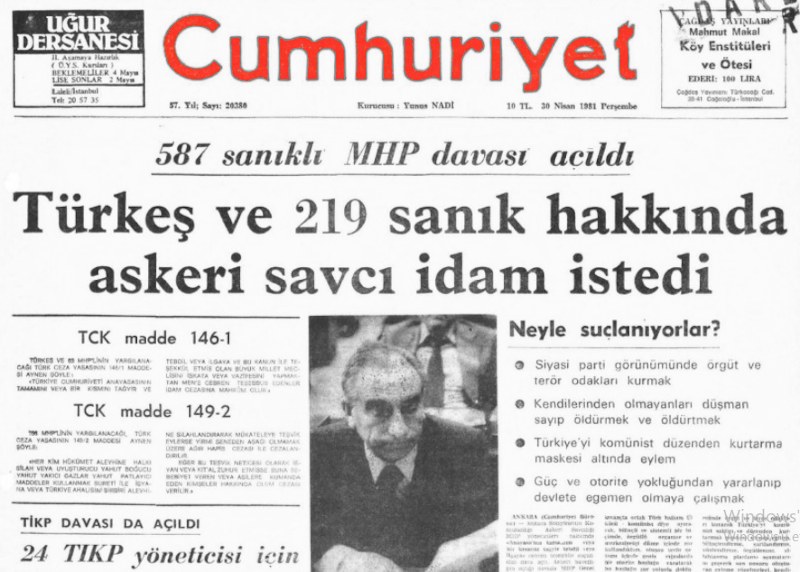

By signing off on sensational actions and massacres, the MHP systematically continued its strategy of preparing the ground for a right-wing military coup and finding a place for itself in this coup. Ultimately, their efforts were reciprocated on September 12, 1980. However, even though the coup was made against the rising socialist struggle, it also shut down the MHP and arrested their managers because it it needed an impartial appearance to ensure social legitimacy and public support. This caused great confusion and consternation within the MHP.

MHP members, who had always stood against the “danger of communism” and who did not hesitate to commit murders and massacres for the “survival of the state”, were now tried by soldiers who had been their favoured. Türkeş expressed this dilemma and their mission, which identified them with the coup, in the letter he wrote to the commander at the head of the coup (Kenan Evren) the following: “Your declarations since September 12 are a confirmation of the thoughts that we have been trying to defend for years and will continue to defend under all circumstances, in a different style.”19

The statement “Our ideas are in power, but we are in prison” expressed by Agah Oktay Güner, Deputy Chairman of the MHP at that time, in his defense of the martial law court, summarizes the relationship between the military coups and the MHP.

February 28, 1997: Ambivalent Attitude Against the Post-Modern Coup

The founder and undisputed leader of the MHP, Türkeş, was faced with another problem of military intervention, one and half months before his death, for the last time. The unrest experienced in the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) during the period of REFAHYOL20 government was gradually increasing; in particular, the second chairman of the General Staff, Gen. Cevik Bir, was making statements against the government, including while in Washington, emphasizing that “they will not compromise on Ataturk revolutions, democracy, and secularism.” MHP leader Türkeş supported this memorandum with the following words: “He made a very good statement. The TSK has always been the guardian of the republic and Kemalism, and it will continue that sacred duty.”21

At the NSC meeting held four days after Çevik Bir’s statement, commanders handed a memorandum to Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan. The REFAHYOL government under the prime ministry of Necmettin Erbakan, after some resistance, was forced to resign.

Meanwhile, Türkeş died shortly after the memorandum, on April 4, 1997, at the age of 80, from a heart attack. After a turbulent process in the MHP, Devlet Bahçeli became the new chairman on July 6, 1997. Bahçeli was elected the second chairman of the MHP after Türkeş’s 25-year-long presidency – except for mandatory breaks during periods of arrest and political banishment.

Bahçeli’s attitude toward the 24 February intervention would be similar to that of Türkeş against the March 12 intervention. He never took a stand against the intervention, and conducted an inconsistent policy. For example, while he appeared to be against the ban on the headscarf, which is one of the symbols of the intervention, he made MPs wearing a headscarf (in the Turkish Grand National Assembly) wear a wig. In the 1999 general elections, his party became a partner in the government, and he himself became Deputy Prime Minister. During this period, he continued his inconsistent approach and used the discourses of “turban drama” and “outdated clothing” together.

August 2, 2004: To the Generals Intervention Acquire Call

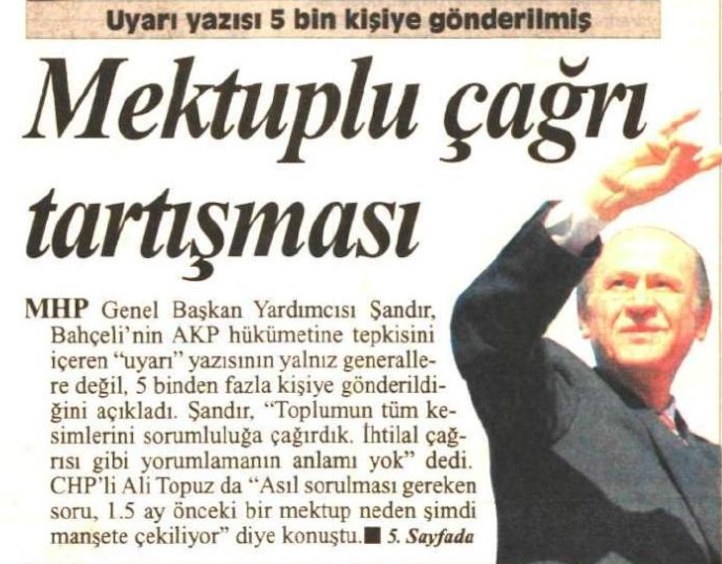

One of the most prominent examples in the history of the coups is that the MHP, whose party was left out of parliament in the 2002 elections, sent a letter to 313 active-duty generals in 2004 to warn the AKP government.

Against the accusations of ‘calling for a coup’ in the letter sent with the signature of Deputy Chairman Mehmet Çandır, though it was known that Bahçeli sent it, which is indisputable, Çandır made the following statement:

“The army is also part of society. Today, the TSK represents 3 to 4 million people, including their families. Moreover, we did not send it to 313 generals, we sent it to the addresses of those we know. There is no point in making any other meaning. So, there is no such thing as calling the military for a coup.”22

The fact that Bahçeli, who accused retired admirals’ the press release as coup plotting, called on the generals to ‘intervene’. must be a joke – a traditional one – of MHP history.

2007 April 27: Bahçeli Benefiting from the e-Memorandum

The MHP, which could not enter the Parliament because it fell below the 10% electoral threshold in the 2002 elections, experienced a military intervention process for the first time without having a representative in the Parliament. Upon the expiration of President Ahmet Necdet Sezer’s term, different factions nominated different presidential candidates. Abdullah Gül, who was the AKP’s candidate for president, according to the constitutional regulation of the time, seemed to have won the election of the president by the Turkish Grand National Assembly.

However, the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) published a statement on its website on 27 April 2007 stating that it was against allowing political Islamist (Abdullah Gül) to be president. In addition, the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) filed a lawsuit with the Constitutional Court, stating that the vote by the Turkish Grand National Assembly was invalid. Because of the court’s decision against Abdullah Gül and the soldiers’ e-memorandum, the AKP decided to renew the elections for the Turkish Grand National Assembly.

Opposed to the candidacy of Abdullah Gül even before the military’s announcement, Devlet Bahçeli accused Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of creating conflict and destabilizing the election process, rather than the soldiers who produced the memorandum.23 On the day the memorandum was published, he continued his accusations and stated that Erdogan was involved in political gambling, making the following assessment:

“Prime Minister Erdogan has taken a political gamble which will have dire consequences. It was clearly understood that the Prime Minister and his party saw the office of the Presidency as the seat of political and ideological mission. It has been revealed that this crippled mentality, which sees the Presidency as the last fortress to be conquered, wants to use this supreme position as a means of reckoning with the state. As a result, the presidential election has been given an ideological content and quality for the first time in our political history.”24

Bahçeli, who directed all his criticisms at Erdogan and the AKP, does not say anything about the soldiers who intervened in politics during this period. Today, Bahçeli, who defends the abolition of the Constitutional Court at every opportunity, defended the decision of the Constitutional Court on Abdullah Gül with these words: “It was clearly understood that the Prime Minister and his party see the office of the Presidency as the seat of political and ideological mission.”25 Of course, these contradictions are not surprising for those who know Bahçeli.

Cementing the Fascist Power Base

Interpreting the statement made by the retired admirals regarding the Montreux Convention as a “call for a military coup” does not coincide with MHP’s own history of support for military interventions or today’s realities. These admirals have no power or means to take action. The admirals who led the preparation have always supported the AKP’s foreign policy (especially in Libyan and Eastern Mediterranean issues) until April 5. Then what is the reason for this attitude of MHP?

As can be seen, the history of the MHP is intertwined with support for military interventions. The only military intervention that MHP opposed from the very beginning was the failed coup attempt on July 15, 2016. Recep Tayyip Erdogan liquidated the coalition of coup-plotters within the military, police and judiciary (with which he had shared the power until then) after this military coup attempt. This afforded a great opportunity for MHP to become a ruling partner, and it established the People’s Alliance with AKP in 2016. The Alliance subsequently reorganized the state in ways the MHP had long sought. The reason why the MHP uses ‘anti-coup’ rhetoric today is not because it is against any military intervention, but out of the concern to protect the reactionary fascist power base cemented in the AKP-MHP alliance. •

Endnotes

- The Montreux Convention Regarding the Regime of the Straits is a 1936 agreement that gives Turkey control over the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits and regulates the transit of naval warships. The Convention guarantees the free passage of civilian vessels in peacetime, and restricts the passage of naval ships not belonging to Black Sea states. Erdogan is trying to divorce the Montreux Convention with a project called Kanal Istanbul, which coincides with America’s interests. Of course, this is not the only reason. The enormous profits that Kanal Istanbul will create is to whet Erdogan’s appetite. For a summary about the Montreux Straits Convention and Kanal Istanbul, see: wikipedia.org.

- The veteran journalist Doğan Özgüden writes about Türkeş’s liquidation: “Before this showdown within the MBK, the name of Alparslan Türkeş was at the forefront, as the “mighty colonel of the revolution”, with the responsibilities of a leader. But in the meantime, Türkeş’s past was also revealed, and it was learned that he had once been arrested for racism. “9 Light” projects were pacing around, worries that Turkey was being dragged into an openly fascist regime grew stronger day by day. ” (Doğan Özgüden (2010). Vatansız Gazeteci: Volume 1. İstanbul Belge Yayınları, p. 236.)

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, November 14, 1960.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, June 8, 1963.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, June 8, 1963.

- Uğur Mumcu (1993). 40’ların Cadı Kazanı. Istanbul: Tekin Yayınevi, p.88.

- Zihni Çetiner (2018). Ölümü Paylaştılar: Bir İhtilaci, Bir Devrimci, Bir Fedai. İstanbul: e Yayınları, s.54.

- This is not the first arrest of Alparslan Türkeş. In 1944, he was arrested in Racism-Turanism Case and was sentenced to 9 months and 10 days in prison. Since he had been under arrest for 1 year, he was released. Later, his sentence was overturned by the court of appeal. The case was reopened – in another court – and all defendants were acquitted. Interestingly, in 1948, Turkes, who should have been expelled from the army under the laws of the time, was sent to the United States for training. After being trained in counterinsurgency for two years there, Türkeş returned to Turkey and became commander of “guerrilla school” in Çankırı. In 1955, he went back to the US and worked directly at the Pentagon. He returned to the country in 1958 and was among the organizers of the coup two years later. For detailed information, see Fatih Yaşlı (2019), Antikomünizm, Ülkücü Hareket, Türkeş: Türkiye ve Soğuk Savaş. Istanbul: Yordam Kitap, p.24-31.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, April 8, 1971 and December 23, 1971.

- Cumhuriyet, June 6, 1972.

- Tanıl Bora and Kemal Can (2019). Devlet, Ocak, Dergâh: 12 Eylül’den 1990’lara Ülkücü Hareket. İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, p.26.

- Cited in Cumhuriyet Newspaper, March 20, 1980.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, June 22, 1977.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, September 14, 2020.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, October 3, 1978.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, October 4, 1978.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, October 5, 1978.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, December 30, 1978.

- Cited by Tanıl Bora and Kemal Can (2019). Devlet, Ocak, Dergâh: 12 Eylül’den 1990’lara Ülkücü Hareket. İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, p.78.

- REFAHYOL: the name given to the government, which was established on 28 June 1996 and was forced to resign after the military memorandum on 28 February 1997, including Refah Party that Recep Tayyip Erdogan grew up in and Doğru Yol Party.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, February 24, 1997.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, August 3, 1997.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, April 25, 2007.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, April 27, 2007.

- Cumhuriyet Newspaper, May 2, 2007.