The Fortunate Marxist: Ernie Tate (1934-2021)

Born poor on Belfast’s Shankill Road in the midst of the Great Depression was certainly no entré to a life that would cross paths with Bertrand Russell, Vanessa Redgrave, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Simone de Beauvoir. Ernest (Ernie) Tate would nevertheless work closely with luminaries such as these and many others who, like him, opposed the war in Vietnam in the 1960s. A lifelong revolutionary socialist, Tate was a leading organizer of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, worked for Russell’s Peace Foundation and its International War Crimes Tribunal, and partnered with the then leftist, David Horowitz (now a prominent conservative spokesman), in taking the anti-war side at an Oxford Union debate.

This was quite something for a lad who dropped out of high school before he was 14. As a teenager Tate apprenticed as a machinist’s attendant in the Belfast Mills. At that young age, Ernie could look forward to a life of dreary, non-union factory labour, his day commencing with the screech of workplace sirens. Keen to escape this fate, a 21-year-old Tate emigrated to Canada in 1955.

Young Ernie soon crossed paths with Ross Dowson, proprietor of the Toronto Labour Bookshop, a pioneering figure in the small Canadian movement of dissident communists who aligned with Leon Trotsky. Dowson, whose brothers Murray and Hugh, were also part of this oppositional politics, ran for mayor in Toronto under the banner, “Vote Dowson, Vote for a Labour Mayor, Vote for the TROTSKYIST Candidate.” His campaigns, at their highwater mark in the late 1940s, garnered 17 percent of the vote.

Tate, who landed his first job at Toronto’s premier department store because his Ulster lineage seemingly aligned him with the store’s patriarch, Timothy Eaton, quit in disgust when he found out that his two-week paycheque totalled $60. He found better paying work in a variety of factory employments at Maple Leaf Milling, Radio Valve, and Amalgamated Electric. But Tate longed for more out of life than a mundane job.

Joining and Learning

The young man soon joined Dowson’s Socialist Educational League. A stern taskmaster, Dowson schooled the new recruit in the rudimentary texts of revolutionary Marxism, tutored Tate in public speaking, and assigned him tasks of writing for and selling the League’s newspaper, Workers Vanguard.

Not yet 25, Ernie’s competence and commitment attracted the attention of the international leadership of the Trotskyist movement. The Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in the United States called on him to help in recruiting youth in the late 1950s. When in New York on this assignment, Ernie met Hannah Lerner and she returned to Toronto with him, where they married in 1957. During these years, Tate also twice attended an SWP educational centre, the New Jersey Mountain Spring Camp, his last participation in the classes offered there being in 1960.

In Canada, Dowson sent Tate on cross-country tours. He lived out of a truck, and sold revolutionary literature to pay for his meals. It was “missionary work” for socialism. He saw the country, made contact with workers, and crossed paths with all manner of militants, including Communist Party members fleeing the Soviet Union’s sinking political ship. In the aftermath of Nikita Khruschev’s 1956 speech revealing Stalin’s atrocities many dissident and disillusioned communists were finally ready to talk to a Trotskyist revolutionary. It was all, in Tate’s words, a “terrific education.”

At the height of the Cold War, in which Moscow and Washington seemed trapped in an irrational race to stockpile more and more nuclear weapons, Tate took umbrage at the building of an official fallout shelter at Queen’s Park. He brazenly defaced the ridiculously inconsequential plywood and cement structure, spray painting “Ban the Bomb” on one of its walls. Hauled into court, and fined $50 for public vandalism, Tate was unrepentant. He declared that he was prepared to take to graffiti again if it might impress upon people the necessity to halt the arms race.

The Toronto Socialist Educational League grew, merged with like-minded radicals in Vancouver, and became the League for Socialist Action (LSA). Its members played a leading role in the Fair Play for Cuba Committee in the early 1960s. They also harboured black radicals like the Monroe County, North Carolina advocate of armed self-defence against racist attack, Robert F. Williams, when he fled the United States. On the run from the FBI, Williams was designated “armed and dangerous.” The LSA harboured the African-American fugitive, distributed Williams’s magazine, The Crusader, and helped him abscond to Cuba.

Tate spent much of the early 1960s on the west coast. Hannah and he parted amicably, but the two did not divorce until the 1980s. Now partnered with another comrade, Ruth Robertson, Tate was charged with consolidating the Vancouver local of the LSA.

He faced an uphill battle to bring warring factions in the small Trotskyist milieu together. His difficulties were compounded by the New Democratic Party (NDP), which the LSA’s members joined to participate in political campaigns and causes. Too often, the Trotskyists found themselves ostracized for their left-wing views, even expelled.

As an unpaid organizer, Tate scrambled to make ends meet. He lived from hand-to-mouth, the material situation quite dire. Ruth experienced a difficult pregnancy, culminating in the birth of a son, Michael, in 1963.

Picket line skirmishes often left Tate responsible for the well-being of arrested comrades. Ernie himself received a suspended sentence of four months on one “obstruction” charge. If there was camaraderie aplenty – Tate enjoying the company of poets like Milton Acorn and Al Purdy who were sympathetic to the LSA cause – Vancouver was nonetheless a difficult assignment.

Tate loved the west coast city and the surrounding natural setting, one of great physical beauty. And the dreary rains reminded him of his Belfast home. But the internal political turmoil dividing comrades in the branch rarely let up. Things worsened when Ernie and Ruth separated, and she departed for Toronto with their son.

UK in the Sixties

With the SWP looking for someone to relocate from North America to London, England to consolidate those sympathetic to its section of the movement, Tate volunteered for the assignment. Arriving in London in 1965, Ernie rented an office for Pioneer Books. It consisted of a few rooms above a butcher’s shop at 8 Toynbee Street, and offered a range of Marxist literature and SWP publications not generally available in London.

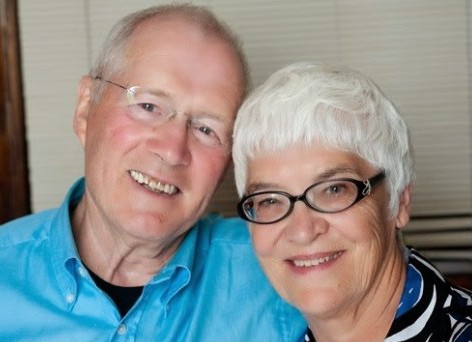

Ernie consolidated a relationship with Jess MacKenzie, a Scottish comrade who had also emigrated to Canada. She came to London in late 1966 on her way to a Brussels Youth Conference. Jess took over running the bookstore, freeing Ernie to spend more time on his organizing work. Mackenzie and Tate would be inseparable for the next 55 years.

Tate’s political work in London was to unify disparate forces aligned with the Socialist Workers Party, which was affiliated with what was known as the United Secretariat of the Fourth International. World Trotskyism had fragmented over the course of the 1950s with different groups claiming to represent the Fourth International that Trotsky had founded in the late 1930s.

In Britain there were three established Trotskyist groups – the International Socialists, Militant, and the Socialist Labour League (SLL) – which also claimed membership in another wing of the Fourth International. Tate’s task was to regroup those outside of these political organizations, long aligned with their own specific bodies and fractured by differences, many of which Ernie thought either arcane or animated by historic but all too personal antagonisms. This necessarily meant delicate negotiations among fissiparous comrades, as well as challenging established rivals on the Trotskyist left, which the SWP thought could never be assimilated.

It was tough sledding. Tate was physically beaten by members of the SLL outside one of their meetings. He had the temerity to sell a pamphlet criticizing the group’s leader, Gerry Healy.

The hooliganism became an international cause célebré. Tate, who publicized the attack as an assault on workers’ democracy, refused to back down when Healy threatened legal action. In the end, the distinguished Polish Marxist, biographer of Trotsky and Stalin, and future G.M. Trevelyan Lecturer at the University of Cambridge (1966-67), Isaac Deutscher, rallied to Tate’s defence. He used his considerable authority within the emerging New Left of the mid-to-late 1960s to summon Healy to his home and, with Ernie present, upbraided the thuggery of the SLL, foreign as it was to the practice of the socialist movement.

Tate, MacKenzie, and a veteran of British far-left politics, Pat Jordan, established the International Marxist Group (IMG) as the section of the United Secretariat of the Fourth International in Britain. Jordan was once described by a London newspaper in 1968 as “the most dangerous man in Britain.”

The IMG became the vehicle through which a small contingent of Trotskyists made common cause with a growing youth radicalization and rising opposition to the war in Vietnam. Tate’s organizational acumen and his personal discipline and commitment were in good part responsible for the successes of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign. He contributed mightily to the work of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation’s anti-war agitation and its War Crimes Tribunal, conducted in two 1967 sessions in Sweden and Denmark. Sartre’s On Genocide (1968) presented some of the findings.

Protest demonstrations in 1967-68 saw Tate join Jordan and the increasingly prominent New Leftist and former President of the Oxford Union, Tariq Ali, on speakers’ podiums at massive anti-war rallies. Currently one of Britain’s leading public intellectuals, and long associated with the New Left Review, Tariq Ali soon became the visible face of the anti-war movement. Recruited to the IMG by Tate, Ali introduced Ernie to celebrities like Vanessa Redgrave, who lent their support to the growing campaign against the American invasion and bombing of Vietnam.

Tate often accompanied Ali, worried that his friend and comrade would be attacked by right-wing opponents. There were indeed skirmishes in which Ernie was physically assailed. One pitched battled, in London’s Grosvenor Square, was ostensibly the inspiration behind the Mick Jagger/Keith Richards anthem to the moment, “Street Fighting Man”: “Ev’ry where I hear the sound/Of marching charging feet, boy/’Cause summer’s here and the time is right/For fighting in the street, boy.”

At a massive rally in Hyde Park, October 27, 1968, Tate and others addressed a massive throng of 200,000 in what is remembered as one of the great anti-war protests of the 1960s. The Guardian found Ernie anything but a poster-boy for the flamboyant counter-culture of the time. This “able Ulsterman in his early thirties, with unmodishly short dark hair, the black-rimmed spectacles of an advertising executive, and a terse, direct, manner,” seemed an incomprehensible incongruity.

Return to Canada

For all the advances made, and exhilarating struggles, Ernie felt he should return to Canada, where he could secure paid employment and contribute materially to the support of his son. He had originally signed on to devote two years to the work in Britain, and that had stretched into four. Financial support that Tate expected to be forthcoming from the LSA in Canada rarely materialized. So in 1969, Ernie and Jess returned to Toronto, needing some time to recharge their batteries and get themselves on a more secure economic footing.

They found the LSA much changed. It had grown significantly, its membership now in the hundreds. Ross Dowson seemed uninterested in Ernie taking up a paid position within the LSA.

Jess, whose experience in running a bookstore was considerable, was passed over when the organization was looking for someone to oversee their Cumberland Street shop. She found paid employment at Ma Bell and worked with a dedicated corps of women’s liberation activists. They played important roles in advocating for women’s reproductive rights, defending Dr. Henry Morgentaler from vigilante attack and legal assault, and putting out an early women’s liberation newspaper, Velvet Fist.

Ernie and Jess thus remained in the LSA, but distanced themselves somewhat from the leadership. Tate continued to be a member of the International’s Control Commission. The couple remained affiliated with the LSA and its successors for years, outlasting Ross Dowson. Younger LSAers clashed with Dowson over a number of issues, including how to relate to the NDP and Canadian nationalism. Dowson left the organization to form the Forward Group in the early 1970s.

Ernie remained a senior voice within the LSA, advising comrades on the best ways to weather the storm of Dowson’s departure, fuse with other Fourth International-affiliated groups to form the Revolutionary Workers League (RWL) in 1977, and move the new organization in more decisively working-class directions.

Eventually, however, Ernie and Jess found that the SWP-affiliated Canadian section of the Trotskyist movement was not what it had once been. The RWL’s “turn to industry,” which Tate had hopes would integrate the Trotskyist movement more effectively with trade unionism and its struggles, never really jelled. Instead it descended into a wooden insistence that all comrades find factory jobs, abandoning professions, higher education, and much of their sense of self. Even getting a trade was frowned upon, regarded as joining the privileged, aristocratic section of the working class.

More and more, the RWL took its cues from an SWP that Tate thought obsessed with otherworldly assessments of an impending revolutionary class struggle that was supposedly erupting from below. As comrade’s lives were squandered in factory employments where the scope for union work was limited, the American leadership removed itself more and more from the terrain of international politics, where the Trotskyist movement had always flourished.

As the 1990s opened with the Iraq War, the RWL, now renamed the Communist League (CL), had become little more than an appendage of the SWP. It no longer published its own press, but sold the SWP’s Militant. Tate, his politics forged on the anvil of anti-war movements, was disgusted when the CL absented itself from protests, which some described as “patriotic” and “anti-American.”

By this point, Ernie and Jess had left the RWL, departing in the late 1980s. They never, however, renounced their understandings of the importance of the organized revolutionary movement, or the ideals and principles animating their involvement in it. Ernie remained throughout his life a revolutionary socialist and committed Marxist. As he moved out of the RWL, he picked up his longstanding activism in the labour movement.

Upon returning to Canada in 1969, Ernie worked for a time as a stationary engineer in Toronto’s west end Canada Packer’s plant, and was a union steward with the Packinghouse Workers Union. Upgrading his work skills at Ryerson Polytechnic (where his essays won academic prizes), Ernie ended up employed as a shift, then chief, engineer at Domtar Papers from 1975-1977.

He was hired at Toronto Hydro in 1977, where he worked until he retired in 1995. Active in Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) Local One (which eventually amalgamated with Local 1000), Ernie served as a chief steward and helped to galvanize the somewhat somnolent union, which had not taken job action for well over a decade. As vice president of the local, Tate was one of the leaders of a successful 1989 strike, working with President Rob Fairley and a team of union militants.

Tate continued to be employed at Toronto Hydro into the 1990s, working in energy management and conservation. Eventually, he was assigned to City Hall, coordinating Hydro’s relations with the municipality. He played a key role in the late-1990s building of a united front that opposed the Mike Harris Conservative government’s plan to privatize the province’s hydro-electrical power industry.

Over the course of the last decades, Ernie and Jess were ever-present in Toronto’s broad, left-wing community. They attended rallies and demonstrations, public forums and left-wing gatherings, radical cultural events and anti-war protests. Active in Toronto’s Socialist Project, Ernie and Jess were enthusiastic supporters of the struggle to up the minimum wage. They connected with younger activists in the Fight for $15 and Fairness.

Elders of the left, the revolutionary couple travelled to socialist conferences, in New York, Chicago, London, and elsewhere. In 2019 Ernie was a featured speaker at an historic gathering addressing the life and work of Leon Trotsky, held in Havana, Cuba.

With Jess’s collaboration, Ernie published a two-volume memoir of his life on the far left in Canada and Great Britain. Revolutionary Activism in the 1950s and 1960s (2014) is a unique resource, a rewarding read for anyone interested in a gritty account of mid-twentieth century revolutionary movements.

It has recently been a valued source of information for the 2020-21 Undercover Policing Inquiry, taking place in England. Its hearings have revealed the illegal and immoral activities resorted to as police agents surreptitiously wormed their way into left wing organizations like the IMG. Its office keys were copied and passed on to MI5, which subsequently burgled the group’s premises to secure membership lists and financial records. These undercover officers – at least six of whom were, at various times in the late 1960s and early 1970s, tasked with spying on or reporting about Tate – went so far as to form intimate relationships with targeted female leftists.

One of Ernie’s last political acts was to provide compelling testimony to these hearings. He condemned the “gross violations of people’s civil liberties” that had taken place over many years, orchestrated by “the British security services.” Tate expressed the hope that the Inquiry would lead to “legislation and public oversight” limiting the ability of the police and other forces of the state to “harass those who happen to be critical of society or are fighting for social change.”

Hope in the Future

A working-class autodidact, Ernie Tate was a literate and cultured man, able to reflect engagingly on art and literature, film and music. He could build a cottage and renovate a house, organize a demonstration, engage a crowd, and convince others of the need to use their particular talents to fight for a better world. A love of food and sociability, valued friendships and good health, were paramount in his everyday life.

Tate was an example of what the working-class is capable of at its best. He found in revolutionary Marxism answers to big questions. This body of thought defined his approach to life within a capitalism whose accomplishments he recognized but whose acquisitive individualism, exploitative essence, and myriad oppressions he abhorred.

Ernie understood well the strengths of the Old Left in which he was educated, but he appreciated as well the promise and possibilities of the many New Lefts that he saw come and go, all of which he regarded with a critical but buoyant hope.

Revered and respected among Trotskyists throughout the world, Ernie was a man of deep convictions. He held to them, through thick and thin. Compromise over cherished principles was not something he could countenance. Yet he was also capable of great warmth and generosity, which he routinely bestowed on those with whom he disagreed. His smile enticing, he could laugh at himself as well as the absurdities of a social order he knew was sick to its core.

At a book launch for his Revolutionary Activism I spoke of Ernie’s sacrifices for the revolutionary left. Not one to hold his tongue, Ernie upbraided me. His life had not been one of sacrifice at all, he insisted. Rather, it was a unique adventure, one in which the rewards received and work conducted in the struggle to build socialism far outweighed anything else that might be taken into consideration. He was a happy man, comfortable in the sincere belief that he was fortunate to have had the opportunity to do what he had done.

Ernie Tate died at his Toronto home on February 5, 2021, aged 86, succumbing to pancreatic cancer that he battled for months. He was cared for by his loving partner and political collaborator, Jess MacKenzie, and will be sorely missed by many. He leaves a legacy of his example, one that will guide those fighting for the day when, “The Internationale/Will be the human race.” •

This article first published on the Canadian Dimension website.