Friedrich Engels’ Thinking on Science in These Times

Reflecting on the contributions of Friedrich Engels (1820 – 1895) on his bicentenary brings three issues to mind. The first issue is, how do we read his writings today? A lot of his writings were polemics against defenders of the existing order, or those proposing theories that ran counter to Marx and Engels’ views on the struggles of the working class for a new and just society. To understand this point, we have to consider what Engels was writing against, as those figures, such as Eugen Dühring, live on only because of Engels’ Anti-Dühring. The second problem is the language of the text. It is written for its time (and space) and, therefore, takes for granted much of what we may not be aware of today. The third problem is that when it comes to science, we barely recognize the terrain about which Engels was writing. The subject matter – the sciences – have moved far away from Engels’ times.

So why do we need to plow through polemical texts of Marx and Engels, written against people whose writings have otherwise been forgotten? There are two reasons for going back to the basics, particularly as science is often presented as neutral, and autonomous from society. Instead, science is inextricably linked to the classes that control society and therefore also control the development of science.

It is no accident that big science in capitalist countries is tied to either war or the greed of capital. This is especially being sharply reflected during the present pandemic when we find that a large number of vaccines are for-profit, even if they have been funded by public money. Or when we see the link between weapons and science research in universities. J.B.S. Haldane, the well-known evolutionary biologist and British Marxist, had said, “… even if the professors leave politics alone, politics won’t leave the professors alone.” So science and scientific research have always been political even if individual scientists, in their own view, are not.

Not Just Academic

The second reason is that science and technology are not just academic disciplines. They have been acting as the motors of development in recent times, even if the development takes us in dangerous directions. It is not possible to talk about the dangers of nuclear-armed, hypersonic or space-based weapons and the danger they pose to humanity without a knowledge of these issues. Or how Google or Facebook and their version of surveillance capitalism are changing what we know, and capitalism itself.

The US withdrawal from almost all nuclear restraint treaties and its formation of Space Command poses new dangers. Yet, there are virtually no protests of the kind we saw during the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or later in the 1980s against the development of the neutron bomb and Reagan’s Star Wars program. While the weakness of the peace movement is not entirely due to the lack of politics in the scientific community, nevertheless, this is one of its significant weaknesses. Scientists were a vital component of the peace and the anti-nuclear weapons movements after World War II.

In the present scenario, there is a need for the left to be able to enter the arena of science and technology, not simply by talking about the consequences of the work of the practitioners but also to excite their imagination through a Marxist view of science and technology. Without these sections of our society, we will be much weaker in arguing on a host of issues, from nuclear war, public health and the COVID-19 pandemic to surveillance capitalism.

Marxism has always attracted scientists, doctors and technologists, as it provides a larger framing of science in society and connects it to the living problems of society. Similarly, the history of technology, its relationship with science and production, becomes clear when we look at the COVID-19 pandemic as an example of what advanced capitalist countries can do if their economies are threatened as opposed to when infectious diseases are only a problem of the poorer countries.

People’s Science Movement

Will this automatically lead to people realizing the relationship between capital, profits and public health? Not unless we can bring our understanding to the people through a larger people’s science movement; or a people’s health movement. And for that, we need to enter the larger scientific community.

This is where Engels and his materialist dialectics becomes important to us. Both Engels and Marx had an enormous interest in the sciences of the day, which they followed closely. Marx was deeply interested in technology, as can be seen in his writings on the technological changes in the textile mills of England. In his work on ground rent, he wanted to know the impact of the use of fertilizers on soil productivity. But when it came to writing on science, he let Engels, who followed science more closely, lead the way. It was Engels who wrote on dialectics in Anti-Dühring, contrasting it with the metaphysical thinking of Eugen Dühring. He elaborated what materialist dialectics means in Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy and his unfinished book Dialectics of Nature.

If the laws of Hegelian idealist dialectics are imposed on nature, philosophically, it shows that there has been a general retreat both from dialectics and a materialist view of nature. Instead, the realist school, closest to materialism, while accepting the external reality of the world that science describes through its theories, is reluctant to call itself materialist. Materialism is a “tainted” word, with its association to Marx, Engels, and later the communists. The retreat from dialectics has also been through a rejection among scientists of a need for a philosophy of science and a view that science itself is enough, and no larger organizing principles of science are required.

Dialectics provides larger organizing principles through which we can unify different parts of science. Underlying dialectics is the belief that everything including matter is in motion, or in a process of change. When we look at society or nature, instead of looking at them as if they are frozen in time and space, we have to look at them from the point of view of change.

Engels in Anti-Dühring enunciates the three principles of dialectics: quantitative to qualitative change (or what physicists today would call phase change), the role of contradictions in nature, and new emergent properties rising out of increasing complexity (negation of the negation). Instead of calling them laws, which in science tends to limit them to a specific phenomenon, these should be looked at as larger organizing principles, within which we understand the scientific laws.

Marx wrote that he did not derive his economic laws from dialectics, but showed that after deriving the laws of capital, they conformed to the laws of dialectics. Engels similarly does not prescribe dialectical laws to science but showed that laws of nature that have been discovered in science can be framed within a dialectical framework.

Engels never finished Dialectics of Nature. Haldane, in his preface to the 1939 publication of Dialectics of Nature, regrets that it remained unpublished for a long time, and writes, “Had his remarks on Darwinism been generally known, I for one would have been saved a certain amount of muddled thinking.” One of its unfinished fragments is on the role of labour in human evolution, more specifically the evolution of the hand. It is the evolution of the hand through the process of labour – creating tools – that distinguishes humans from apes. Engels writes, “Thus the hand is not only the organ of labour, it is also the product of labour.” It is not the evolution of the hand that led to our evolution as a species but the coevolution of the hand and labour as a historical process.

There has been a criticism of Engels for subscribing to Lamarckism with respect to evolution and therefore criticizing how he describes the inheritance of the skills of labour. What people forget is that Charles Darwin (1809 – 1882) while propounding natural selection also supported Lamarck’s inheritance of acquired characteristics as a driver of evolution. In his theory of heredity, which he published in 1868, Darwin called his evolutionary theory pangenesis, which contained both natural selection and Lamarckian inheritance of acquired characteristics. Mendelian genetics was not known to biologists at the time, and it was only much later that biology incorporated Mendelian genetics.

Engels’ major contribution was to show that nature was not merely unchanging, or a backdrop, for its history. He showed that nature, instead of being unchanging, is also in evolution; just as the species in nature are. Nature and its species, including humans, are both a part of this dynamic process of change and evolution, which is a historical process.

Division of Labour

One of the major focuses of study for both Marx and Engels was the study of science and technology and their relationship with production. While Marx focused more on technological changes in industry and agriculture, he needed somebody to understand not only such changes but also the advances in science that made the technological changes possible. Though Marx followed the developments in science, he often turned to Engels for help in understanding how the latest developments of the sciences affected technology practice.

Engels had not only written about the condition of the working class in England as a consequence of the industrial revolution but also worked as a partner in a Manchester textile mill. He was very much a part of the ongoing industrial revolution in England and counted Carl Schorlemmer, a chemist and a lifelong communist, among his close friends. It was Schorlemmer, a leading scientist in his times, a fellow of the Royal Society, who helped both Marx and Engels in their understanding of science.

The division of labour between Marx and Engels was also about writing on science, or in combating the metaphysical thinking that denied change as a fundamental property of nature and society. If Capital: Volume I is one of the most incisive accounts of the history of technology in the industrial revolution, Dialectics of Nature, even in its unfinished form, shows the extent and the depth of Engels’ understanding of the developments in science taking place during his lifetime.

There have been many critics of Marx and Engels, who hold that Marxism suffers from a productivist bias that considers nature an infinite resource for the development of productive forces. This has been the criticism of Gandhians in India as well, that Marxism and capitalism both focus on industrial development that would change nature and lead to an ecological crisis.

On the contrary, Marx and Engels have written extensively on the enormous damage to nature and the inability to sustain production that can follow an unthinking expansion of production. The examples included the desertification of Mesopotamia and the disastrous policy of the British in India that destroyed its cotton weavers. Marx writes in Capital: Volume I, “[T]he English cotton machinery produced an acute effect in India. The Governor General reported 1834-35: ‘The misery hardly finds a parallel in the history of commerce. The bones of the cotton-weavers are bleaching the plains of India.’”

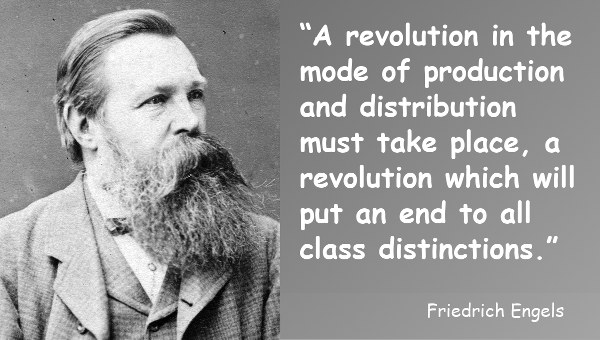

Engels was fully aware of the threat that capitalism posed to the productive capacity of nature. John Bellamy Foster writes in Monthly Review on November 1,

“Engels had indicated [in Anti-Dühring] that the capitalist class was ‘a class under whose leadership society is racing to ruin like a locomotive whose jammed safety-valve the driver is too weak to open.’ It was precisely capital’s inability to control ‘the productive forces, which have grown beyond its power,’ including the destructive effects imposed on its natural and social ‘environs,’ that was ‘driving the whole of bourgeois society toward ruin, or revolution.’ Hence, ‘if the whole of modern society is not to perish,’ Engels argued, ‘a revolution in the mode of production and distribution must take place.’”

Instead of being oblivious to the destruction of nature by capital, Engels and Marx were aware of the crisis in nature that it was creating. The ecosocialist movement has brought out the need for the working-class movement to address the problems of a capitalist mode of production that does not think beyond the next quarter’s profits and the value of their shares in the stock market.

The left movement has to bring in the best of scientific and technological minds to fight the multiple disasters that the greed of capital is creating. This is what the independence movement in countries like India did in their struggles against colonialism. We need to show that other alternatives exist within science, technology and society. Yes, science and technology by themselves will not solve the problems of society and nature. But their contribution is necessary to find a solution to such problems. This is the example that Engels set before us, and which we need to follow. •

This article was produced in partnership by Newsclick and Globetrotter.