Here Comes Bourgeois Socialism – Again

What should we think of the recent praise of “the welfare state” and public services coming from different voices among the ruling classes in the world? Their conversion is as sudden as miraculous; they recall much better the holy history of the apostles than the secular history of societies.

The Financial Times editorial of April 3rd, entitled “Virus lays bare the frailty of the social contract,” offers an exemplary case. It says:

“Radical reforms – reversing the prevailing policy direction of the last four decades – will need to be put on the table. Governments will have to accept a more active role in the economy. They must see public services as investments rather than liabilities, and look for ways to make labour markets less insecure. Redistribution will again be on the agenda; the privileges of the elderly and wealthy in question. Policies until recently considered eccentric, such as basic income and wealth taxes, will have to be in the mix.”

“Radical Reforms”

Here are words and expressions which had been tabooed over the past thirty years by neoliberal dogma and which have been, and still are, part of the common repertoire of trade unions and social movements: “public services,” “redistribution,” “privileges (…) in question,” “basic income,” “wealth taxes.” Written in the Financial Times, they astonish the reader.

Here are words and expressions which had been tabooed over the past thirty years by neoliberal dogma and which have been, and still are, part of the common repertoire of trade unions and social movements: “public services,” “redistribution,” “privileges (…) in question,” “basic income,” “wealth taxes.” Written in the Financial Times, they astonish the reader.

As much as French president Emmanuel Macron surprised French public opinion during his intervention on March 12, 2020, especially when he explained: “What this pandemic is already revealing is that free healthcare without income conditions, career or profession, our welfare state, are not costs or burdens but precious goods, essential assets when fate strikes. What this pandemic reveals is that some goods and services must be placed outside the laws of the market.”

In the same manner, the head of the Catholic Church, Pope Francis, has called for the cancellation of poor countries’ debts. Bill Gates and Emmanuel Macron did likewise, more specifically, for poor African states for the latter.

Reforms and the Reproduction of the Established Order

How should we interpret these ideological reversals beyond condemning their hypocrisy?

First, an initial critical reflex consists in not remaining prisoners of ruling-class discourse. “Just as one does not judge an individual by what he thinks about himself, so one cannot judge such a period of transformation by its consciousness, but, on the contrary, this consciousness must be explained from the contradictions of material life, from the conflict existing between the social forces of production and the relations of production.”1 This means confronting these ruling-class discourses with the exercise of power and the policies implemented. In his time, Nicolas Sarkozy also said he was in favor of a “refounding” of capitalism, of regulating finance and of a new balance between the market and the state. It was in September 2008 in his speech in Toulon.

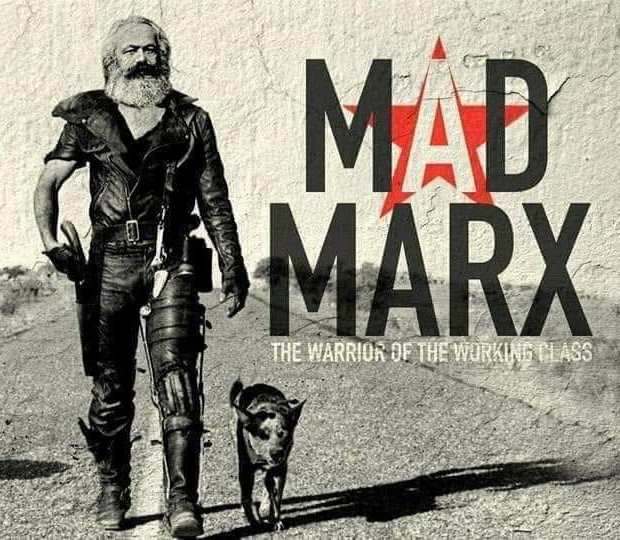

Then, a second critical axis of current ruling-class reformism is to reveal its partial, inconsistent and, in reality, profoundly conservative character. Marx and Engels offer an important critical resource in this sense when he describes the features of “conservative or bourgeois socialism” in The Communist Manifesto (1848):

“A part of the bourgeoisie is desirous of redressing social grievances in order to secure the continued existence of bourgeois society.

To this section belong economists, philanthropists, humanitarians, improvers of the condition of the working class, organizers of charity, members of societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals, temperance fanatics, hole-and-corner reformers of every imaginable kind. This form of socialism has, moreover, been worked out into complete systems.

We may cite Proudhon’s Philosophie de la Misère as an example of this form.

The Socialistic bourgeois want all the advantages of modern social conditions without the struggles and dangers necessarily resulting therefrom. They desire the existing state of society, minus its revolutionary and disintegrating elements. They wish for a bourgeoisie without a proletariat. The bourgeoisie naturally conceives the world in which it is supreme to be the best; and bourgeois Socialism develops this comfortable conception into various more or less complete systems. In requiring the proletariat to carry out such a system, and thereby to march straightway into the social New Jerusalem, it but requires in reality, that the proletariat should remain within the bounds of existing society, but should cast away all its hateful ideas concerning the bourgeoisie.

A second, and more practical, but less systematic, form of this Socialism sought to depreciate every revolutionary movement in the eyes of the working class by showing that no mere political reform, but only a change in the material conditions of existence, in economical relations, could be of any advantage to them. By changes in the material conditions of existence, this form of Socialism, however, by no means understands abolition of the bourgeois relations of production, an abolition that can be affected only by a revolution, but administrative reforms, based on the continued existence of these relations; reforms, therefore, that in no respect affect the relations between capital and labour, but, at the best, lessen the cost, and simplify the administrative work, of bourgeois government.”

The context today is, of course, not the same. The current world is indeed profoundly different from the world in which this text of Marx and Engels is inscribed. However, it is important to remember the following common point which allows us to grasp the news of the excerpt quoted above: today, as in the late 1840s, individuals and groups of the ruling classes are trying to find solutions to the most manifest social dysfunctions which endanger the social body as a whole. Unlike the reforms put forward by the class struggles from below, the reforms proposed by the ruling classes – their “socialism” – aim to make temporary concessions and to intervene in social relations in favor of the greatest number in order to save themselves and consolidate the established order and the domination of the possessing classes. Marx’s criticism offers the possibility of understanding the blind spots of dominant reformist discourses in order, precisely, to emancipate ourselves from them, and thus, thwart the traps of domination. •

Endnotes

- Karl Marx, “Preface,” A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, 1859.