The Transnational Activism of Dockworkers

“Interfere with the foreign policy of the country? Sure as hell! That’s our job, that’s our privilege, that’s our right, that’s our duty” – Harry Bridges, 1974.

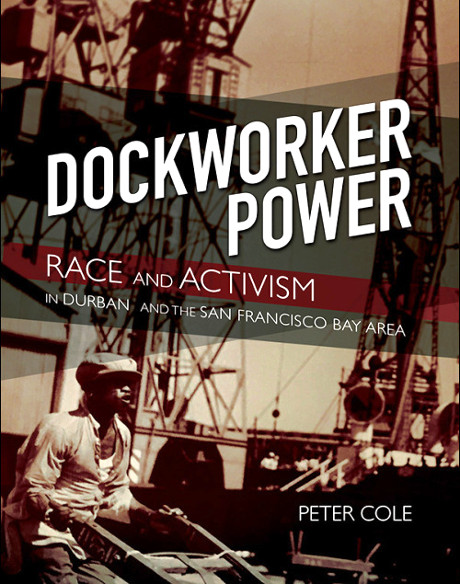

Dockworkers have power. That’s the basic argument of my book which is named – yes – Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area. Using comparative, transnational, and global labour historical methods, Dockworker Power brings to light perhaps surprising parallels in the experiences of dockers half a world away from each other. It’s the first comparative history of dockers in ports in what, loosely, have been called the Global North and the Global South, and among the first spanning both the traditional and the container eras of shipping. Historically, dockworkers have been able to change their conditions and promote social justice causes around the world. Notably, they continue to operate at a strategic choke point of the global supply chain, and they still appreciate their importance despite being largely invisible to the wider public.

Though many folks are unaware of it, including a surprising number of labour and maritime historians, the very term used for workers’ most powerful weapon has maritime origins! In 1768, as historians Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker recalled, sailors “struck (i.e. took down) the sails of their vessels, crippling the commerce of the empire’s leading city [London] and adding the strike to the armoury of resistance” (Linebaugh and Rediker, 2000).

Dockworkers and sailors are particularly able to strike for, as the saying goes, “The ship must sail on time.” Dockers understood that stopping work at a strategic moment had tremendous potential. Lou Goldblatt, a long-time leader of the union representing dockers on the US West Coast, explained: “The shipping industry has a feature that should never be underestimated – the economic power of the longshoremen [the typical term in the US for dockers] is fantastic compared to most workers; the amount of economic leverage they have.” Though most people might not appreciate this reality, employers are not among them.

Much of my book examines how dockers have used their power not only to benefit themselves but also to assist others. For one, dockworkers in each city drew on longstanding radical traditions to promote racial equality. Specifically, Durban dockers played a pivotal role in the struggle against apartheid while those in the San Francisco Bay Area greatly contributed to the African American civil rights movement. Considering both South Africa and the United States are societies built on the foundation of racial capitalism, antiracist actions taken by labour unions are particularly important to chronicle.

The book’s second major theme examines technological change. In both Durban and the Bay Area, dockworkers persevered when a revolutionary new technology – container ships – sent a shockwave of layoffs through the industry.

International Solidarity

The third main topic explores how dockers in both these vital port cities possess long histories of international solidarity activism. That is, Durban and SF Bay Area dockworkers have refused to work cargo or entire ships for political reasons. Harry Bridges, the founding and long-time president of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), explained why in the quote that introduces this essay.

As early as 1935, Durban dockers refused to load food aboard an Italian ship to protest that country’s invasion of Ethiopia. Similarly, in the late 1930s, San Francisco longshoremen refused to load metal aboard Japanese ships to protest that country’s invasion of China. In both cases, dockers took a clear stand against fascism.

Much of my research uncovers the San Francisco Bay Area dockworkers’ decades-long effort to help overthrow the apartheid regime in South Africa. While South Africans played the primary role, the struggle against apartheid became a truly global social movement. As early as 1962, San Francisco longshoremen refused to unload South African cargo, in coordination with anti-apartheid activists. In the aftermath of the Soweto student uprising, the ILWU’s Bay Area local created the Southern Africa Liberation Support Committee to assist those fighting in South Africa and across the region. Their most impressive effort was a ten-day boycott of South African cargo in 1984 – the largest direct, workplace action in the United States in the anti-apartheid movement. Their actions inspired many others in the Bay Area. In 1990, when Nelson Mandela first visited the United States, he devoted 10% of his speech in Oakland, before 60 000 people, to thanking the ILWU.

My book also explores Durban dockers who, in 2008, refused to unload Chinese weapons intended for neighbouring Zimbabwe, which is landlocked and thus dependent on South Africa and Mozambique for imports and exports. That April, then-president Robert Mugabe had unleashed his police and army to kill and intimidate Zimbabweans in an effort to defeat the opposition party, led by trade unionist Morgan Tsvangirai. The Durban dock leaders who I later interviewed made clear that they acted in solidarity with their fellow workers in Zimbabwe: they boycotted a shipload of weapons and ammunition that would kill more Zimbabwean workers. They also appreciated that, in decades past, Zimbabweans had aided black South Africans in the struggle against apartheid.

‘Block the Boat’

Even more recently, dockworkers in both ports have demonstrated solidarity with the Palestinian liberation movement. The comparison between South African apartheid and the Israeli treatment of Palestinians is imperfect (as is every comparison), but many South Africans are quite clear: when they visit Israel/Palestine, they loudly decry the situation – and name it apartheid. For instance, when the Israeli-owned Zim shipping line has docked in Durban, there have been protests on multiple occasions.

Similarly, as early as its 1988 convention, the ILWU officially criticized the Israeli treatment of Palestinians by proclaiming Israel guilty of “state-sponsored terrorism.” In fact, it was the African American Leo Robinson – the Bay Area leader of ILWU anti-apartheid activism – who was among the most outspoken on this matter. In the 2010s in the Bay Area, Arab American activists increasingly have taken the lead on this issue. They worked with allies inside Local 10 to ‘Block the Boat’, preventing the loading and unloading of cargo from Zim line ships, most dramatically and successfully in 2014. Their commitment to black internationalism and leftist politics have resulted in multiple transnational work stoppages to protest authoritarianism.

I don’t only study the past because it’s fascinating. I also do so because, like Howard Zinn, I want to understand the present in order to build a better future. One lesson of my book is that the greatest power ordinary people possess is when they’re organized, especially in unions, and that workers’ greatest weapon is the strike. As the Wobbly1 leader Big Bill Haywood said, “If the workers are organized, all they have to do is to put their hands in their pockets and they have got the capitalist class whipped.”

Secondly, since resources always are limited, we have to be strategic. Dockworker Power makes clear that those interested in expanding worker and union power should prioritize shipping because 90% of the goods we consume still move by ship for at least part of their journey. More broadly, we should strive to organize workers up and down the entire supply chain. Dockworkers aren’t necessarily more important than warehouse workers, truck drivers, and so on; they’re just better organized and so have more power now. In short, Dockworker Power offers historical perspectives on how workers have changed their conditions and world. •

References

- Cole, P. (2018), Dockworker power: race and activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay area, University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Linebaugh, P., and Rediker, M. (2000), The many-headed hydra: sailors, slaves, commoners, and the hidden history of the revolutionary Atlantic. Boston: Beacon Press.

This article first published on the Global Labour Column website.