The War on AMLO

Ten weeks into the administration of progressive president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), the Mexican right has made it clear how it plans to oppose him: not as an adversary to be defeated, but as an enemy to be destroyed. And in a war of this kind, as the Spanish saying goes, Todo vale. Anything goes.

The first of the false furors flared up even before AMLO took office, when former presidents Vicente Fox and Felipe Calderón – both from the conservative National Action Party (PAN) – criticized his decision to invite Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro to his inauguration, setting off a tempest-in-a-teapot firestorm within the nation’s corporate media. Inviting foreign heads of state to an inauguration, of course, is part and parcel of diplomatic protocol, something both Fox and Calderón had adhered to when inviting then-president Hugo Chávez to their respective ceremonies.

The first of the false furors flared up even before AMLO took office, when former presidents Vicente Fox and Felipe Calderón – both from the conservative National Action Party (PAN) – criticized his decision to invite Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro to his inauguration, setting off a tempest-in-a-teapot firestorm within the nation’s corporate media. Inviting foreign heads of state to an inauguration, of course, is part and parcel of diplomatic protocol, something both Fox and Calderón had adhered to when inviting then-president Hugo Chávez to their respective ceremonies.

But hypocrisy was no object when it came to the PAN’s attempts to tie AMLO to the Bolivarian Revolution, an obsession that dated to the party’s shadowy attack ads in the 2006 election and repeated faithfully through last year’s campaign. When, during his inaugural speech in Congress, AMLO read out Maduro’s name among a list of the foreign leaders in attendance, deputies from the PAN leapt up on cue and, with cries of “Dictator!,” ran to the front of the chamber to unfurl a banner condemning the Venezuelan head of state (a stunt strangely not repeated for the president of Cuba, Miguel Díaz-Canel).

First Steps

AMLO’s first major initiative as president was to reduce the bloated salaries of the top federal bureaucracy, fulfilling a key campaign pledge; the Maximum Salaries Law, in fact, was the first to be passed by the MORENA Congressional majority when it took office in September of 2018. But opposition parties quickly challenged the law’s constitutionality, arguing that it violated the separation of powers.

It was a strange argument to make, especially in light of the fact that Article 127 of the Mexican Constitution expressly stipulates that no public servant can earn more than the president; the law, in fact, was designed to enshrine the constitutional provision in secondary legislation. No matter. The leader of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) in the Senate, Osorio Chong, fustigated against “a climate of lynching” against the judicial branch “propitiated by the government and its party,” going so far as to claim that the measure would encourage not only the removal of judges and magistrates but aggression against them.

The judges themselves then got into the swing of things, beating their breasts in a public display of inconformity that led some observers to wonder why they hadn’t bothered to protest in the same way the abuses of power, disappearances, and violence that led to some 267,000 homicides over the last two administrations.

The attempt to portray the judiciary as the victims was audacious, to say the least. Federal judges are among the highest paid members of the federal bureaucracy, with the eleven members of the Supreme Court – which proceeded to place a temporary stay on the Maximum Salaries Law – earning upwards of 600,000 pesos ($31,470 US) per month, including benefits, several times more than the president and more than the average Mexican makes in eight years (the justices have since agreed to reduce their base salary by 25 per cent for 2019).

But such was the fever to portray AMLO as an authoritarian dictator-in-waiting – and such was the president’s political acumen in choosing an initial battle that commanded near-unanimous popular support, forcing his knee-jerk opposition into a neat trap – that it was willing to defend the indefensible when the wisest course, seemingly, would have been to pick a smarter battle. But in a war of attrition, losing battles is part of the strategy. The key is to attack, always attack.

#AMLOAsesino

The day before Christmas, three weeks into the president’s term, a tragic accident gave the Mexican right another chance to strike. Ten minutes after taking off, the helicopter carrying the governor of the State of Puebla, Martha Erika Alonso, and her husband, former governor Rafael Moreno Valle, both from the PAN, crashed into a cornfield in the town of Santa María de Coronango, killing everyone on board.

The accident occurred just ten days after Alonso had belatedly taken the oath of office after defeating the MORENA candidate, Miguel Barbosa, in a judicially contested July election which, according to a study by the Iberoamerican University, contained “multiple and grave inconsistencies” that called into question the results.

Within hours, the hashtag #AMLOAsesino (AMLO Assassin) had become a national trending topic, which it was to remain for several hours. Closer investigation, however, revealed that, far from being a spontaneous outpouring of citizen internauts blaming AMLO for the accident, a deliberate campaign of defamation was at work.

According to an analysis performed by the news site Sinembargo.mx, the trend benefited from “artificial and coordinated support” by a series of anti-AMLO bots. “The way in which the clusters gathered around the #AMLOAsesino trend showed that they did not arise from an organic dialogue in which users with distinct profiles converge and contribute different points of view,” stated author Ivonne Ojeda de la Torre. She continued:

“The farm of recently created accounts that participated in the trend from the first moments after its appearance contributed to positioning [it] through simultaneous retweets and spam, distinguishing it from the organic dialogue that resulted from the tragedy … The tweets were published constantly, but without generating discussion, behavior that is characteristic of artificially amplified trends.”

The following day, De la Torre published a second analysis showing how, since 2011, the PRI has generated an army of bot accounts to create and promote trends, spread fake news, attack opponents, and buy votes, using money of doubtful origin that, unlike traditional campaign spending, is much harder to trace. In the days following the accident, moreover, residents of Puebla began receiving robocalls with a supposed survey asking whether the cause of the crash was “mechanical error” or a planned “attack.” The goal, clearly, in the absence of any evidence whatsoever, was to sow doubts through innuendo and insinuation.

In a very overt accompaniment to this covert activity, former presidents Fox and Calderón again leapt into the fray to fan the flames in the most irresponsible of possible ways. “We demand an explanation!” Fox wailed in a tweet. “It is hard to accept this coincidence after such a stiff democratic battle for Puebla.” Calderón was only slightly more discreet, calling for “an impartial investigation into the causes of the accident.”

So feverish did the cyber-conspiracy theorizing become that AMLO, at his morning press conference on December 26, used unusually strong language to shut down the speculation. “There’s been an environment created by the same conservatives as always,” he stated in response to a question about the accusations. “Not all, but a mean-spirited minority … These are neo-fascist groups that are very upset by the triumph of our movement and are trying to affect us, to stain us. They won’t succeed.”

Turning the Screws

On the foreign-relations front, there are also signs that the United States is beginning to turn its screws on AMLO. Although the Trump administration has systematically vilified Mexicans for years, his language regarding its new government has been surprisingly measured. Venezuela may have changed that.

On January 4, Mexico refused to sign the “Lima Accord” calling on Nicolás Maduro to stand down from his second presidential term, slated to begin on January 9. The accord was a product of the Lima Group, comprised of Canada and a dozen right-wing Latin American governments, whose purpose has been to provide soft cover for the United States by pushing for regime change in Venezuela. Even though Mexico is a part of the group, thanks to the previous Peña Nieto government, Deputy Foreign Minister Maximiliano Reyes declared in a statement: “We call for reflection in the Lima Group about the consequences for Venezuelans of measures that seek to interfere in internal affairs.”

When, on January 23, the head of the Venezuelan National Assembly Juan Guaidó declared himself “interim president,” Mexico reiterated its position, citing Article 89 of the Mexican Constitution which mandates non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries. “It’s not that we’re in favor or against. We’re following through with our institutional principles,” AMLO said in his daily news conference on January 24th.

In doing so, he was effectively resurrecting the Estrada Doctrine, which formed the basis of the nation’s independent foreign policy in the mid-twentieth century, even during the height of the Cold War. Named after Foreign Secretary Genaro Estrada (1930-32), the doctrine calls on Mexico to back the peaceful settlement of conflicts and neither support nor reject foreign governments or governments-in-transition, since to do so would be to violate state sovereignty. On January 25, Mexico offered to mediate a peaceful resolution to the conflict, in conjunction with Uruguay. Two weeks later, at the meeting of the International Contact Group in Montevideo, Mexico, Bolivia, and the Caribbean Community (Caricom) bucked the majority of attendees by refusing to sign the call for new elections in Venezuela.

The Mexican right, of course, fell over itself to attack the government’s position. On the same day as Guaidó’s self-proclamation, the PAN debuted a similarly self-proclaimed foreign policy by rushing to recognize him. Columnist Leo Zuckermann at the newspaper Excelsior declared AMLO to be “on the wrong side of history.” With slightly more nuance, analyst Carlos Bravo Regidor tweeted: “The terms ‘non-intervention’ and ‘neutrality’ do not serve to explain the position of the Mexican foreign ministry regarding the Venezuelan crisis. To prefer mediation is to seek to intervene to defuse the situation; to promote negotiation in search of a political settlement is not to remain neutral.”

On January 29, American secretary of state Mike Pompeo cancelled a planned trip to Mexico to discuss the issue of Central American migrants traveling through the country to the US border. Although no explicit reason was offered for the cancellation, it came amid mounting controversy over Mexico’s position on Venezuela.

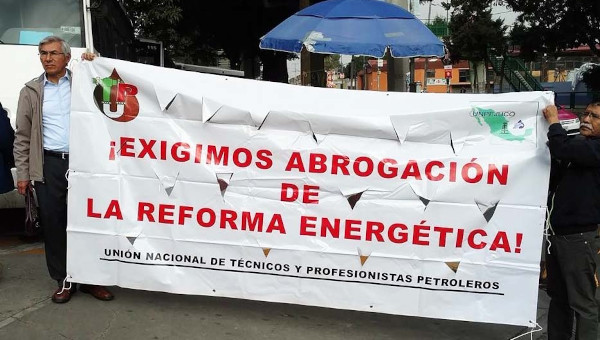

On the same day, the Wall Street rating agency Fitch downgraded the credit rating of the state oil company Petroleros Mexicanos (PEMEX) an entire point from BBB+ to BBB-, citing “unfunded pension requirements, negative equity and exposure to political interference risk.” The downgrade, which places PEMEX’s bonds just above junk status, will make it much more expensive for the company to borrow funds to upgrade its operations, neatly cancelling out the cost-cutting savings AMLO has sought to carry out. As PEMEX continues to contribute nearly a fifth of government revenues, even after being bled by a major privatization effort by former president Peña Nieto, this may also wind up squeezing the government’s ability to deliver on its social-spending promises.

At his daily press conference the next day, AMLO ridiculed both the decision and its timing: “What these organizations do is very hypocritical … They allowed the looting [of Pemex], they endorsed the so-called energy reform, they knew that foreign investment didn’t arrive, investment in PEMEX didn’t increase and that was what caused the decline in petroleum production. And they never said anything.” He added, “They maintained a complicit silence and now that we’re rescuing PEMEX, they come out with their recommendations and … ratings.”

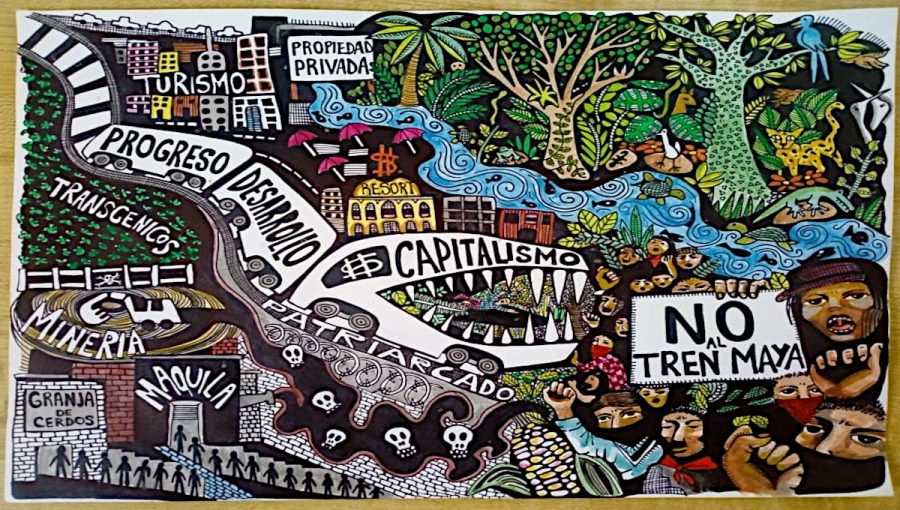

As if anticipating this changing mood, Time Magazine – ever a faithful mouthpiece of empire – plopped Mexico into its top-ten list of “biggest geopolitical risks of 2019.” In the words of editor-at-large Ian Bremmer, AMLO’s “bid to roll back the opening of Mexico’s economy, orthodox macroeconomic policies, privatizations, and deregulation threaten a return to the 1960s. In 2019, he’ll spend money Mexico doesn’t have on problems like poverty and security that resist straightforward solutions. And as he centralizes power, policymaking will become more erratic.”

The choice of decade is curious, as Mexican growth rates in the 1960s averaged some 6.5 per cent per year, three times higher than the neoliberal era inaugurated in 1982. Curious, as well, that his concerns do not extend to the case of Latin America’s other newly inaugurated president, Jair Bolsonaro. As Bremmer breezily concludes, “the public, the media, and Brazil’s political institutions won’t allow space for any dangerous centralization of power.”

Avoiding Erosion

For now, AMLO’s position appears stable: latest polls give him a staggering 86 per cent approval rating, economic indicators are solid, and the machinations of the Mexican right – especially in light of the abject failures of recent conservative administrations – appear both overwrought and sophomoric. But as the screws continue to tighten, a number of options could be mobilized down the road, such as a combined media, diplomatic, and economic campaign to weaken, discredit, and isolate AMLO, one that brings together the domestic and international actors analyzed here.

Delegitimation, after all, is a gradual process of erosion, and when it comes to progressive governments, with their reduced margin for error, missteps that in themselves seem minor can prove fatal. It is imperative, then, that the radicalized political base that elected AMLO does not allow itself to become lulled into complacency by the false belief that winning office is the same as conquering power. •

This article was originally published in The Jacobin