Labour in the Age of Duterte: The Pacific Plaza Strike

The lesson of the Pacific Plaza strike is that workers’ solidarity, not presidential promise, will end contractualization.

“Kung titingnan natin sa umpisa, pumasok ako ng Pacific nung construction pa lang, hanggang maintenance” [In the beginning, I began at the Pacific Plaza during construction, in maintenance]. This isn’t an uncommon sentiment for the workers of Pacific Plaza. Most of them have spent almost two decades tending to the needs of the residents of the lush twin-condominium towers, only to find themselves bearing the brunt of what would turn out to be one of 2018’s major labour struggles.

The Pacific Plaza workers’ strike in the heart of Bonifacio Global City turned half a year old last February, having weathered so many challenges – from dispersal on the first day of the strike, typhoons, a steadily depleting strike, to temporary restraining orders (TRO) ignored by management.

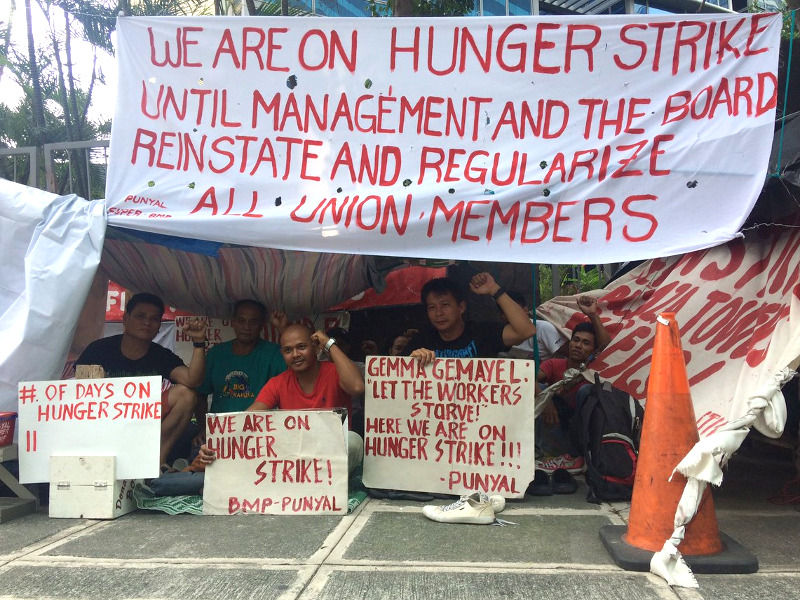

Caving in is, however, the furthest thing from the mind of these workers, who have held one of the longest hunger strikes by labour since the 1980s, as part of their campaign to pressure the Pacific Plaza management to regularize 17 contractuals terminated last July 2018. It is this perseverance in the face of the ruthless management of a prestigious institution that has attracted much attention from media, students, and even the Catholic Church.

Unlikely Union

In most establishments, management has strictly enforced legal distinctions between regular workers and contractual workers, the most important being the contractuals’ insecurity of tenure. Many workers have, unfortunately, internalized these differences in status. One of the features of the Pacific Plaza strike that has caught the attention of observers of the labour scene is the way its participants have united despite their status distinctions, something that rarely happens.

“Para sa akin, yung ginawa nila doon sa labing-pito na kontraktwal, gagawin din nila sa amin. Sa loob pa lang, kahit kontraktwal, kasama namin sila, ginagawa nila yung trabaho namin, at yung trabaho nila, ginagawa namin” [For me, what management did to the 17 contractuals, they will eventually do to us, regulars. Inside, we could see that the contractuals were with us, doing the same kind of work] said Edgar Virtudazo, a regular employee and an officer of the Pacific Plaza union, Pacific Plaza United Action of Labour – SUPER (Punyal-SUPER, for short), when asked about why they formed the union with the contractuals.

The distinctions don’t matter, Edgar emphasized, and said that the union had organized themselves in this way because it made sense for them to do so. To leave out the contractuals would have been to dilute the struggle and recreate the same kind of distinctions management has imposed on them.

This wasn’t the first time the workers had tried to organize into a union. The first union in Pacific Plaza, composed of only the regular workers, was formed in 2015. However, during their first collective bargaining agreement (CBA) negotiations, management promised higher pay and better working conditions on the condition that the workers voluntarily dissolve the union. Under such pressure, the workers caved in, but it only took a short while for them to realize that they had been duped. Within that time period, management enforced more stringent rules, but no longer having a union, the workers were powerless to do anything about it.

It took almost three years for the workers to muster the courage to organize again, only this time including the contractuals. With the formation of their union with the contractuals, management made its move: on July 6, 2018, a total of 17 contractuals, half of the 34 members of the union, were terminated, with “end of service,” colloquially known as endo, as the officially stated reason. This was in clear violation of the rights of the contractuals whose contracts ran to December that year.

A month later, the union went on strike on the basis of union busting, when negotiations carried out at the level of the National Conciliatory and Mediation Board (NCMB) hit a dead-end.

On the first day of the strike, the union was dispersed and the workers were detained by the police. The stated reason? That workers could not carry out a strike on private property – a senseless rationale since strike actions by workers are guaranteed by the constitution.

After that fateful day, the union decided to come back to Pacific Plaza armed with a letter from the Department of Labour and Employment (DOLE) Secretary Silvestre Bello III stating that the police and the Bonifacio Global City marshals could not intervene in the strike action since it was covered by DOLE guidelines drawn up with the Philippine National Police (PNP) and the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG). The strikers felt confident management would come to terms.

Six Months at the Picket Line

Six months passed. Six months at the picket is a feat, but also a struggle in and of itself. Perseverance has been accompanied by hardship, so that today, spirits are undoubtedly low. The picture of victory which seemed on the verge of attainment has begun to blur.

“Gusto na namin matapos ito, kasi…masakit na,” [We want to finish it, because … it hurts] Ka Edgar said, managing to smile as he did so.

It’s very rare to find the words to describe a strike, but Ka Edgar phrased it well for the workers of Pacific Plaza. The battle is truly far from over for the Pacific Plaza workers, but it is costly in terms of human suffering. People have had to tighten their belts. Families’ incomes have been sharply reduced. But even more serious than material privations was the demoralization that was lurking at the margins of the strike, ready to strike and spread if given the chance.

Ka Edgar’s admission that things were hurting was followed, however, by a realization that the struggle was still worth pursuing. We asked him that if he had known that the strike would be this long-drawn out process, would he still have gone out on strike? After a pause, he said that if by some miracle he had foreseen how things would turn out, he would still have chosen to go out. Ka Edgar isn’t wrong when he says that strikes, much like the one at Pacific Plaza, are bound to happen.

Management Colludes with Manpower Agencies

The Pacific Plaza workers are a particularly interesting case for labour in the country. Their strike makes a pointed critique of the current DOLE Department Order 174 and the subsequent Executive Order 51 of the President, both of which were proclaimed as the solution to the contractualization issue.

Contractualization was one of the main issues in the 2016 election campaign, with candidate Rodrigo Duterte promising to abolish it. Along with other promises, Duterte’s vow to end contractualization led to a whopping 16 million votes. Nearly three years into this administration, however, the promise remains unfulfilled.

Currently the law does not prohibit bilateral contractual arrangements (better known as direct hire). This arrangement includes the probationary 6-month period and covers seasonal and project-based workers. Controversy, however, attaches to the trilateral arrangements that involve a principal or establishment that is serviced, a manpower agency, and a contractual worker.

Under the current department and executive orders, the only kind of trilateral arrangement that is banned is “labour-only contracting.” A manpower agency is considered a labour-only contractor if it does not have capital investment in the form of equipment, tools, uniforms, and other items necessary for the performance of work; it does not have direct power or control over its workers; and the jobs contracted out to its workers are not directly related to the main business of the principal, that is non-core functions. Compliance with these criteria would mean that manpower agencies providing janitorial, security, and other non-core functions would be the only ones that would be classified as legitimate subcontractors.

The fact is that most workers in trilateral arrangements are either performing core functions, are under the direct control of the principal, or use equipment belonging to the principal. This is the issue at the heart of the Pacific Plaza strike: there is no difference in the work done by the Plaza’s regular workers and the contractual workers that are nominally under the control of a manpower agency. More broadly, manpower agencies providing contractual labour have become a convenient vehicle for management to avoid regularizing workers that perform core functions and are under its direct control.

What Lies Ahead?

Definitely all hope is not lost for the workers, although at times many feel as if there is no hope left. “Bago ako lumabas naisip ko na obligasyon ko na ito. Papanindigan natin ito,” were Ka Edgar’s words of advice to workers who might be hesitating to fight for their rights.

Ka Edgar’s wife, Mildred Virtudazo, a housewife for most of her time before the strike, has become a de facto union member in the process. She has been to general meetings, has been part of every milestone and landmark of the strike, and even goes to shifts on the picket-line. When asked why she does this, when little to none is asked of her, she says, “Naisip ko na ang laban niya ay laban ko na rin” [I thought this fight was against me]. If there’s anything to describe the incredible sense of solidarity of the Pacific Plaza workers, it would be Mildred’s sentiment. It is a deep understanding that struggles are shared and carried by those who see, understand, and care.

Ultimately, what keeps Edgar and Mildred going is the fervent belief that “winning” the labour dispute is possible. Certainly wins are possible, and the Pacific Plaza strike has created the blueprints for workers everywhere – that it is indeed possible for regulars and contractuals to be organized together, without thinking that they are detrimental to each other’s interests. That in itself is the Pacific Plaza workers’ biggest achievement so far. But, of course, there is no substitute for victory in the strike.

Politically, what is there to do? With the broken promises of the Duterte administration, the actions of the Pacific Plaza workers teaches us that when we look to the most affected by these policies, there is much to learn about how we can make the country better for all of us, most especially for the workers.

We are at a point in contemporary history where labour is resurgent. The struggle against contractualization has reignited the labour movement. In the last three years alone, more than 24 strikes have taken place, compared to the 15 strikes that occurred during the six years of the Aquino administration.

Whatever may be the conclusion of the Pacific Plaza strike, there is little doubt that the practice of contractualization, which has done so much damage to labour in this country, is facing a mortal challenge from its victims. •

This article first published on the rappler.com website.