What Colour is Your Vest?

The Gilets Jaunes Revolt Shaking France

In 1934, the political situation in France was tense and uncertain. The year began with a mobilization of royalist and fascist militias (on February 6) that were followed immediately (on February 9 and 12) by a response from the Communist and Socialist wings of the workers movement. As Norbert Guterman and Henri Lefebvre reported, “all these men are ready for the concrete liberation a revolution would bring – and perhaps also, unfortunately, the mystique and brutal mythology of the fascists” (1999 [1936], 143, trans. SK). When these lines were written in the mid-1930s, France was experiencing a rising tide of grassroots anti-fascist politics culminating in the strike waves of the early days of the Popular Front government. Yet Lefebvre and Guterman’s warning was well-placed. The Popular Front disintegrated due to many contradictions, ultimately giving rise to Marshall Pétain’s collaborationist administration, France’s contribution to fascist regime politics.

History does not repeat itself mechanically. But the revolt of the gilets jaunes (yellow vests) in France underway since November 2018 reminds us that we, too, live in times of deep political uncertainty. Today, there are not two large organized political blocs facing each other in a battle for life and death. The political ambiguities of our age express themselves as contradictions within the gilets jaunes, as well as amidst the range of forces trying to claim them. The early analysis by political anti-racist coalition Comité Rosa Parks is worth repeating:

“This unprecedented mobilization attests to a profound dissatisfaction among the labouring classes (classes populaires) facing precarization and contempt at the hands of elites and state power. It would be wrong and condescending to treat it as a product of far-right manipulation, not the least because the initiators refuse to be appropriated by any partisan organization…. And yet, this spontaneity, which is so original and refreshing, also carries with it strong contradictions that we need to consider so as not to join to the movement blindly and blissfully.” Comité Rosa Parks, November 21, 2018 [Trans. SK]

A Political Football

The gilets jaunes revolt has shaken France with a cascade of actions – roundabout occupations, blockades, roaming demonstrations. The main actors: people who were initially only loosely connected to each other by social and other media. As we write, in early February, some yellow vests are beginning to structure themselves in the form of electoral lists or popular assemblies. Yet the political colours of many vests remain uncertain, as are the political effects of their actions. To this, we can add a curious novelty about the gilets jaunes: they have an incredibly wide range of self-proclaimed supporters: parties, movements, and intellectuals from the far right to the far left. This is true in France and in other places where the symbol of the yellow vest has become a political football.

Next to these political attempts to claim the yellow vests, there has also been an outpouring of analysis. A veritable barrage of concepts has been launched to make sense of the revolt and its broader implications. For example, critics have mobilized terms from French history (‘sans-culottes’, ‘poujadistes’) as well as concepts borrowed from elsewhere to grasp the yellow revolt: ‘the moral economy of the crowd’ (E.P. Thompson), ‘populism’ (Chantal Mouffe, Ernesto Laclau), the ‘multitude’ (Toni Negri), the ‘wages of whiteness’ (W.E.B. Du Bois), ‘imperial lifestyles’ (Ulrich Brand and Markus Wissen), and ‘organic crisis’ (Antonio Gramsci). There is no space here to discuss these analyses. Instead, we offer two anecdotes from our visits to France late last year, a few short preliminary observations about the revolt so far, and three possible scenarios for the future.

Marseille, November 17: Caught off guard (Act 1)

We first encountered the gilets jaunes inadvertently, on the streets of central Marseille on November 17, during what later would be called Act 1, the first in a series of demonstrations held in towns and central cities on subsequent Saturdays. Stefan Kipfer had arrived in Marseille on November 14, just as a large demonstration arrived on the steps of City Hall to protest the complicity of the mayoral majority in the death of eight inhabitants and the evacuation of many hundreds of other residents following the collapse of two buildings on Rue d’Aubagne on November 5. The Rue d’Aubagne is the main street in the Noailles neighbourhood, one of the African-defined immigrant districts that, in contrast to other large French cities, still dominate the heart of downtown Marseille.

We first encountered the gilets jaunes inadvertently, on the streets of central Marseille on November 17, during what later would be called Act 1, the first in a series of demonstrations held in towns and central cities on subsequent Saturdays. Stefan Kipfer had arrived in Marseille on November 14, just as a large demonstration arrived on the steps of City Hall to protest the complicity of the mayoral majority in the death of eight inhabitants and the evacuation of many hundreds of other residents following the collapse of two buildings on Rue d’Aubagne on November 5. The Rue d’Aubagne is the main street in the Noailles neighbourhood, one of the African-defined immigrant districts that, in contrast to other large French cities, still dominate the heart of downtown Marseille.

Staying in a hotel at the bottom of Rue d’Aubagne, Kipfer woke up to an unfamiliar sight on Saturday, November 17: groups of men and women in yellow jackets, mostly in their 30s, 40s and 50s. They wandered along the city’s main drag (the Canebière) or congregating at main intersections to block car traffic. They could be spotted easily not only because of the yellow on their backs. Largely, but not exclusively, white, they stood out from the African-dominated scene that is the Canebière on a Saturday. Both crowds, the protestors and the locals, had one thing in common, however. They were full of weathered faces that reflect the long, tedious working days defined by the diktat of others and the experience of counting each penny at the end of the month. What we witnessed was the inadvertent and uneventful co-presence of spatially segmented fragments of the French labouring classes. In the following weeks, the yellow vest revolt intersected not only with labour activists from the region but also with the ongoing movement against slumlordism, gentrification and municipal corruption that has become a focal point of mobilization from the central city to the housing estates on the North side of Marseille (Fessard, 2019).

The purpose of our stay in Marseille was not to study yellow jackets. After all, Priscilia Ludosky’s online petition against Macron’s gas taxes that helped spark the movement had only been circulating since October 21. The reason was to interview people involved in organizing opposition to the far right, including the Rassemblement National (RN, the renamed Front National). Kipfer spent the Saturday interviewing five experienced activists from far-left, anarchist and autonomist anti-fascist and anti-racist organizations. In both interviews, the gilets jaunes crept into the conversation without prompting. Similar to most on the left in France at that moment, the interview partners were skeptical if not dismissive, treating the gilets jaunes as a golden opportunity for the far right, including the RN and Debout La France which had already endorsed the movement. Given Kipfer’s research, which aims to understand how organizers deal with the normalization of far-right ideas and sensibilities, this skepticism seemed plausible (and remains pertinent today in various respects). One interviewee cautioned, however, and posed the following question: how can we come to definite conclusions about the character and political future of a movement no one really knows or understands yet? This point turned out to be correct also: the gilets jaunes have defied the certainties and convictions of most, including many on the left.

Paris, December 15: Looking from the outside in (Act 5)

The two of us were in central Paris on that day. Normally full of tourists and luxury shoppers, the “beaux quartiers” were unrecognizable. Stores, banks and cafés were mostly closed and boarded up. Streets were blocked off by thousands of police and armoured vehicles. And yet it was certainly festive. At mid-afternoon, hundreds of gilets jaunes occupied squares at the Opera and the Saint Lazare train station; hundreds more were on the Champs-Élysées – the Parisian focal point of the Saturday marches; and yet hundreds more on the streets in between, navigating around police blockades. Earlier in the morning at the Opéra, gilets jaunes got down on their knees with their hands behind their heads to show solidarity with highschool students in suburban Mantes-la-Jolie, who had been subjected to a humiliating mass arrest inflected with neocolonial brutality during a December 6 protest against school reform and university admissions policies.

The two of us were in central Paris on that day. Normally full of tourists and luxury shoppers, the “beaux quartiers” were unrecognizable. Stores, banks and cafés were mostly closed and boarded up. Streets were blocked off by thousands of police and armoured vehicles. And yet it was certainly festive. At mid-afternoon, hundreds of gilets jaunes occupied squares at the Opera and the Saint Lazare train station; hundreds more were on the Champs-Élysées – the Parisian focal point of the Saturday marches; and yet hundreds more on the streets in between, navigating around police blockades. Earlier in the morning at the Opéra, gilets jaunes got down on their knees with their hands behind their heads to show solidarity with highschool students in suburban Mantes-la-Jolie, who had been subjected to a humiliating mass arrest inflected with neocolonial brutality during a December 6 protest against school reform and university admissions policies.

We had never seen Paris like this, part militarized ghost town, part festive street scene. By all accounts, the numbers of protestors during Act 5 were significantly lower than they had been on previous weekends. And yet, the power of the revolt was evident in the grandiose efforts of the state to shut down dozens of subway stations, cordon off train stations, and block off large swaths of the governmental districts on both sides of the Champs-Elysées to prevent an insurrectionary turn of the yellow vest mobilizations. The effect of these actions was to make room, literally, for unexpected encounters among various protesters as well as between protestors and others. Desperate for a washroom and a little warmth, we joined yellow vests from Quimper (Brittany) who were befriending the Parisian bartenders in one of the very few cafés that remained open in the militarized zone. On the street, we followed two young men blaring political singer Rachid Taha at other protesters and the riot police who were changing guard in front of us. On the way back from the Champs-Elysées, we ran into scores of out-of-towners who met up randomly with locals trying to figure out how to reconnect with public transit.

We had never seen Paris like this, part militarized ghost town, part festive street scene. By all accounts, the numbers of protestors during Act 5 were significantly lower than they had been on previous weekends. And yet, the power of the revolt was evident in the grandiose efforts of the state to shut down dozens of subway stations, cordon off train stations, and block off large swaths of the governmental districts on both sides of the Champs-Elysées to prevent an insurrectionary turn of the yellow vest mobilizations. The effect of these actions was to make room, literally, for unexpected encounters among various protesters as well as between protestors and others. Desperate for a washroom and a little warmth, we joined yellow vests from Quimper (Brittany) who were befriending the Parisian bartenders in one of the very few cafés that remained open in the militarized zone. On the street, we followed two young men blaring political singer Rachid Taha at other protesters and the riot police who were changing guard in front of us. On the way back from the Champs-Elysées, we ran into scores of out-of-towners who met up randomly with locals trying to figure out how to reconnect with public transit.

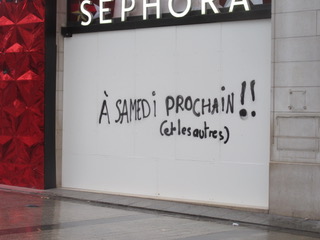

Also right in front of us on that day, on the walls and on people’s vests, ample evidence of the ambiguity of the revolt and those wanting to claim it. The slogans written on placards or sprayed on walls between L’Arc de Triomphe and the Place de la République gave a sense of the sentiments. Beyond the ubiquitous “Macron, Resign!,” the slogans expressed poetic utopianism (“We are green with rage. We would like to see the vie en rose”), joyful determination (“See you next Saturday!! (And all the Saturdays after that)”) and unspecified rage (“Fuck it all”). A hatred of President Macron (“Merry chaos, it is time to pay up, fuck Macron”) extended sometimes to a rejection of all politicians (“Macron, Le Pen, Mélenchon, get lost, all of you”), sometimes to a critique of banks and the media (“Abolish control of the media by the rich”, “Give back the money”). In one instance, class hatred was linked to a hatred of immigrants (when someone added “and the immigrants” to the slogan “Kill the rich”). Slogans of solidarity were easy to find (“High schoolers, University students, Yellow Vests, Solidarity,” “Leave pensioners alone”) but strategic proposals varied widely. Some went much beyond the demand for referenda into autonomist, anarchist and insurrectionist territory (“General blockade,” “ZAD (Zone to defend) everywhere”).

Also right in front of us on that day, on the walls and on people’s vests, ample evidence of the ambiguity of the revolt and those wanting to claim it. The slogans written on placards or sprayed on walls between L’Arc de Triomphe and the Place de la République gave a sense of the sentiments. Beyond the ubiquitous “Macron, Resign!,” the slogans expressed poetic utopianism (“We are green with rage. We would like to see the vie en rose”), joyful determination (“See you next Saturday!! (And all the Saturdays after that)”) and unspecified rage (“Fuck it all”). A hatred of President Macron (“Merry chaos, it is time to pay up, fuck Macron”) extended sometimes to a rejection of all politicians (“Macron, Le Pen, Mélenchon, get lost, all of you”), sometimes to a critique of banks and the media (“Abolish control of the media by the rich”, “Give back the money”). In one instance, class hatred was linked to a hatred of immigrants (when someone added “and the immigrants” to the slogan “Kill the rich”). Slogans of solidarity were easy to find (“High schoolers, University students, Yellow Vests, Solidarity,” “Leave pensioners alone”) but strategic proposals varied widely. Some went much beyond the demand for referenda into autonomist, anarchist and insurrectionist territory (“General blockade,” “ZAD (Zone to defend) everywhere”).

Following that Saturday, we spoke with many activists we know in Paris. They, too, had been on the outside looking in to the gilets jaunes movement. Like our Marseille interlocutors in November, they were not there at the beginning, did not hear the original call or understand where it was coming from. Ex-urban roundabouts, the main stage of yellow vest politics, do not form a part of their everyday life, though they do for the extended families of many of them. They had also wondered early on, in November, if the movement was being organized from behind the scenes by the far right. And yet, despite their social distance and political reservations, all of the activists – variously involved in unions, left political parties, political anti-racism – we met with during five days in Paris were both excited by the potential of the gilets jaunes movement and convinced that the political ambiguities of the revolt were reasons to get involved, not excuses to stay away.

Following that Saturday, we spoke with many activists we know in Paris. They, too, had been on the outside looking in to the gilets jaunes movement. Like our Marseille interlocutors in November, they were not there at the beginning, did not hear the original call or understand where it was coming from. Ex-urban roundabouts, the main stage of yellow vest politics, do not form a part of their everyday life, though they do for the extended families of many of them. They had also wondered early on, in November, if the movement was being organized from behind the scenes by the far right. And yet, despite their social distance and political reservations, all of the activists – variously involved in unions, left political parties, political anti-racism – we met with during five days in Paris were both excited by the potential of the gilets jaunes movement and convinced that the political ambiguities of the revolt were reasons to get involved, not excuses to stay away.

An activist we don’t know, Tristan Petident, published a public Facebook post after taking part in the December 8 mobilization (Act 4) in Paris. He summed up the sense of possibility that opened up in a moment characterized by a decline of the left and of trade unions unable to stop worsening of labour laws and social conditions for nearly a decade:

“In the wake of defeated defensive battles and compromises with successive governments between aimless days of action and rotating strikes, the eruption of the gilets jaunes also means: enough discussion, enough negotiation, enough deal-making. We don’t want a piece of the pie, we want the whole pie…. (I)n this movement, which has collided with society as a whole and therefore our own [left] organizations, there is something elusive that is much more radical and revolutionary than our traditional mobilizations.” [Trans. KW]

Petident went on to describe how he felt compelled to leave a march organized by labour unions and the left on that same day. Despite the decent numbers and the joyful atmosphere in that march, he felt too much a part of “an inside group of activists… where everyone knows each other, everyone shares the same codes, everyone makes their own politics.” It seemed as if he and his fellow marchers were “external” to the gilets jaunes, out of synch with their more dispersed and fluid energies [ibid. trans. SK]. Despite their enthusiasm, Petident’s observations also raise some tough questions about the relationship between the gilets jaunes, the left and the future of politics.

Danger Ahead: taking stock…

At the time of writing, in early February, the gilets jaunes revolt is ongoing. Looking back for a moment, a few things about the gilets jaunes can be said with some measure of certainty.

- Judging by various early surveys and reports, the gilets jaune revolt is largely white and predominantly middle-age as well as cross-class in character, with strong working class and lower middle-class components and a significant minority of women participants. The revolt emerged neither from central cities or postwar suburbs surrounding them but from the automobilized towns, exurbs, employment zones and shopping districts at the edge and between the larger urban centres.

- The revolt opened as a critique of a gas tax increase but quickly broadened to include wider concerns about social injustice. Since the gas tax hike was withdrawn in early December, the main demands of the revolt have gravitated around fiscal justice (lower consumption taxes, higher taxes for the rich and corporations), a higher minimum wage and social service levels, semi-direct democracy (referenda and initiatives) and, increasingly, freedom from state repression. Exclusively right-wing demands (against immigration, for more state authority) and conspiracy theories are present but have not defined the main demands.

- The revolt developed through a novel spatial dynamic of mobilization linking the main sites of occupation and mobilization (traffic roundabouts spread throughout the country) to blockades of infrastructure (highways, toll booths, ports, tunnels, refineries) and demonstrations in larger towns and cities held on Saturdays. This spatial dynamic will force us to revisit the meaning of the ‘right to the city’.

- The multifaceted spatial dynamic of mobilization also created at least punctual points of contact between the yellow vests, organized movements and other social forces, for example unionized workers and highschool students from big-city suburbs and smaller towns. These points of contact and the unpredictability of the revolt has generated much debate on the left about the broader potential of the revolt, including arguments from political anti-racist organizers about the similarities and differences between their concerns and the gilets jaunes demands.

- Similar to movements since the Arab Spring, the occupy movements and the movemens of the squares in Southern Europe, the yellow vest revolt expresses a deep crisis of political representation in France. A large proportion (by some accounts the majority) of protesters express a deep skepticism about organized political forces (parties and labour unions) and reject the distinction between left and right that underpins many of these forces. In this respect, the yellow vest revolt resonates with other attempts to dismiss and transcend the left-right divide: Macron’s Bonapartism and Le Pen’s neofascism.

- The yellow vests have produced a political crisis in France, widening the cracks in the foundation of the Macron government and challenging the solidity of some state apparatuses. Notably in late November and early December, one could smell a whiff of insurrection as France’s combined police forces reached their limits trying to contain the many simultaneous and unconventional mobilizations. More broadly, the gilets jaunes interrupted Macron’s strategy to build a stable cross-partisan bloc to radicalize neoliberalism (Palombarini, 2018). If Emperor-Bonaparte Macron was already in a state of partial undress before November, he is now without clothes.

… And Looking Ahead

The gilets jaunes story is by no means finished. While across Europe, the symbol of the yellow vest is being appropriated by movements with distinct, even antagonistic purposes (from far right to left), in France, weekly demonstrations keep happening and some roundabouts are still occupied. While the mobilizations no longer reach the levels of late November and early December, and many roundabouts have been cleared by the police, efforts are underway to give the yellow vests a more permanent political presence. These include an attempt to build an electoral list for the European elections, strategies to foster organizational links between the vests and the labour movement, and initiatives to create a network of popular assemblies. But even as some gilets jaunes are trying to structure themselves, one question remains glaringly, and at this point necessarily, unanswered. Who will benefit from this very much unfinished revolt and the crisis of political rule it helped deepen and intensify? More specifically, who will manage to hegemonize the meaning of the yellow vest (Boggio Ewanjé-Epée, 2018)? Here are three possible scenarios.

First, will the main beneficiaries be the generic tax-cutters both from within the government and among those further to the right? In French politics, tax revolts and protests against shrinking purchasing power have a complex political history (Spire, 2018). Since the 1980s, they have become a central part of the repertoire of the Front National, a political project of former President Nicholas Sarkozy and part of the broader Euro-American right populist landscape shaped by anti-tax ideologies and car drivers’ mobilizations against taxes and other restrictions. During the yellow vests revolt, generic demands for tax cuts and against tolls and radar controls have generally been overshadowed by redistributive demands for fiscal and social justice (thus picking up, in a sense, on the 2009 revolt in France’s overseas territories). But their presence and persistence (not least among the entrepreneurial elements in the movement) have given Macron, Les Républicains and the RN ammunition to respond to the revolt in the tried and true terms of neoliberal populism (Kouvélakis, 2019).

Second, will the forces of the far right manage to fully redefine ‘yellow’ social demands as claims to the ethno-nation and against ‘foreign’ elements? Various forces of the far right have tried to pick up on elements within the gilets jaunes in order to turn the revolt into an identitarian movement against immigration, social assistance recipients and international conspiracies. These efforts have had only very limited success in terms of shaping the explicit political demands made by the yellow vests. However, even though the gilets jaunes demands are much closer to the social democratic La France Insoumise than to the Rassemblement National, it is possible that the latter, not the former will reap the electoral benefits from the movement. In the absence of a counterforce from the left or from within the gilets jaunes, the RN might do what it has done repeatedly since the 1980s: syphon off electoral support from subaltern social groups by way of ideological osmosis (in this case also via social media) without an organic grassroots presence among these groups or an organizational stranglehold over them. Macron’s own strategy to respond to the revolt from the right will bear a heavy responsibility should the RN profit most from the yellow vest moment. He has offered to discuss immigration quotas, promised to value ‘those who work’ among the gilets jaunes, and used the revolt to expand the already formidable physical, legal and administrative arsenal of repression available to various French state apparatuses.

And, third, will the gilets jaunes help renew left-leaning subaltern political capacities? The social linkages and incipient solidarities built in weeks of blockades and confrontations with the police might turn out to be the first wall in a new bulwark against the far right, which thrives on social atomization and political disorganization. In this regard, the most persistent effort has come from the gilets jaunes in Commercy, a small town in the Northeastern Lorraine region. Twice in December, the Commercy vests called upon everyone in France to replicate their own efforts to organize themselves in local general assemblies. Why? To articulate egalitarian, socially and fiscally just and democratic aspirations and make sure that their capacity to speak is not ‘confiscated’ from above (Gilets Jaunes de Commercy, 2019). 75 delegates from elsewhere heeded these calls and met in Commercy on January 26 to hash out a common position, which is unambiguously left-leaning and explicitly demarcated from fascist and xenophobic as well as sexist and homophobic tendencies (Gilets Jaunes, 2019). Clearly, this is bad news for Macron and the far right. Yet it is too early to tell whether they represent the seeds of a new type of popular counterpower (Balibar, 2018). Nor can we say if or how these assemblies could form a component of a new social bloc against both neoliberalism and neofascism, a bloc composed of distinct working-class segments, the ‘beaufs’ (‘rednecks’ from the hinterlands) and the ‘barbares’ (non-white toilers and inhabitants) (Bouteldja, 2018). •

References

- Balibar, Etienne (2018), “Gilets jaunes: le sens du face à face,” Médiapart, December 13.

- Boggio Ewanjé-Epée, Félix (2018) “Le gilet jaune comme signifiant flottant,” Contretemps November 22.

- Bouteldja, Houria (2018) ‘Beaufs et Barbares: comment converger ?’ December 2, indigenes-republique.fr.

- Collectif Rosa Parks (2018) “Des gilets jaunes au(x) gants noirs: égalité, justice, dignité ou rien!” November 21.

- Fessard, Louise (2019) “Des milliers de Marseillais mobilisés contre le mal-logement,” Médiapart February 3

- Gilets Jaunes (2019) “Appel de la première assemblée des assemblées,” Commercy, January 27. Manif.est.info Posted on January 29.

- Les Gilets Jaunes de Commercy (2018) ‘Deuxième appel des Gilets Jaunes de Commercy: L’assemblée des assemblées’. Le Petit Gilet Number 1, January 4. Public post on the Facebook page of the Gilets Jaunes de Commercy, January 6.

- Kouvélakis, Stathis (2019) ‘Gilets jaunes, l’urgence de l’acte’, Contretemps 19 January, contretemps-eu.

- Norbert Guterman and Henri Lefebvre (1999 [1936]) La Conscience Mystifiée (Paris : Syllepse)

- Marlière, Eric (2019) “Les «gilets jaunes» vus par les quartiers populaires,” Slate January 9.

- Palombarini, Stefano (2018) “Les gilets jaunes, le néolibéralisme et la gauche.” Médiapart December 21 medipart.fr.

- Petitdent, Tristan (2018) “Sur la journée Parisienne du 8 décembre et au delà”, Public post on Tristan Petitdent’s personal Facebook page, December 8.

- Spire, Alexis (2018) “Aux sources de la colère contre l’impôt.” Le Monde Diplomatique December, 1, 22.

- VISA (Vigilance et Initiatives Syndicales Antifascistes) (2018) “Ces gilets bruns qui polluent les gilets jaunes,” Les Dossiers de Visa no 5 www.visa.org.

- Wahnich, Sophie (2018) ‘La structure des mobilisations actuelles correspond à celle des sans-culottes’, Médiapart December 4 medipart.fr.