Mexico’s Energy Transformation?

When fuel prices shot up dramatically two years ago, ordinary Mexicans took to the streets. The gasolinazo, as the abrupt surge in prices was called, was a gut-punch to Mexicans’ strained finances, triggering blockades, occupations, and ransacking at gas stations across the country. A year and a half later, in July 2018, voters rejected the right-wing PRI and PAN parties behind Mexico’s energy reforms, electing Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a storied figure on the Mexican left.

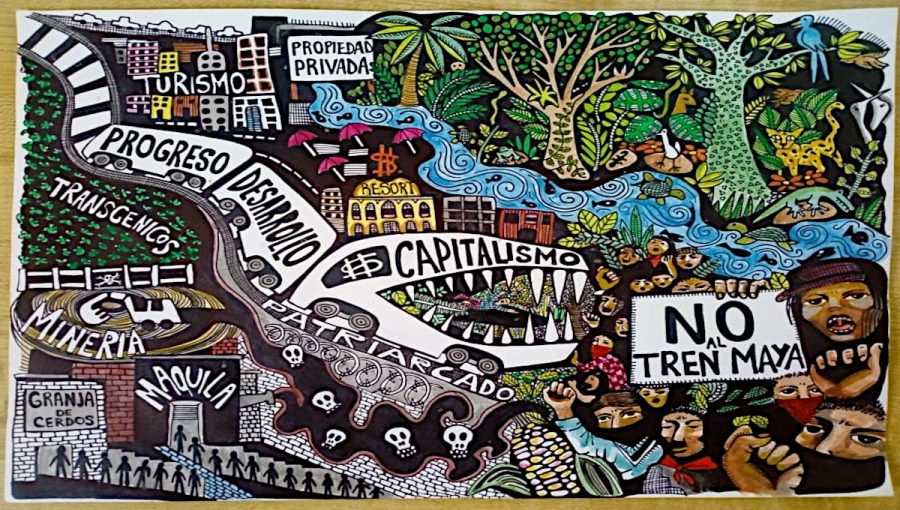

Despite the central importance of energy policy to his election, there has been relatively little discussion of what a López Obrador government might mean in terms of climate policy. López Obrador (also known by his initials: AMLO) ran on a hodgepodge of environmental proposals including a major reforestation project, support for renewables, and support for rural agriculture. At the same time, AMLO’s proposed “Maya Train,” a high-speed tourist train connecting the Yucatán beaches of Tulum and Cancún with famous ruins such as Palenque further south, has raised consternation and doubts from indigenous leaders and environmental activists who worry that the mega-project will cause further damage to protected areas along its path.

Despite the central importance of energy policy to his election, there has been relatively little discussion of what a López Obrador government might mean in terms of climate policy. López Obrador (also known by his initials: AMLO) ran on a hodgepodge of environmental proposals including a major reforestation project, support for renewables, and support for rural agriculture. At the same time, AMLO’s proposed “Maya Train,” a high-speed tourist train connecting the Yucatán beaches of Tulum and Cancún with famous ruins such as Palenque further south, has raised consternation and doubts from indigenous leaders and environmental activists who worry that the mega-project will cause further damage to protected areas along its path.

The new government’s most ambitious action to impact the climate is its crusade to bring Mexico’s national oil company, Pemex, back under public control. If successful, it would strengthen public finances, allowing the government to exercise a sovereign energy policy. While the new government seeks to expand Pemex’s production, de-privatizing Pemex may be a necessary precondition to negotiating a just transition from fossil fuels in Mexico. Oil revenues have been a singular source of income for modern Mexico, and the government will need capital to move off of fossil fuels. The government is taking steps to effectively renationalize Pemex in the interim, but it will have to contend with the country’s dependence on oil exports and its relationship with the United States in the long term. The danger remains that the government will fall into a similar trap as past progressive governments in Latin America, financing poverty reduction through intense resource extraction.

Geopolitics and Rescuing Pemex from the Brink

Surely that would not bring climate progress to Mexico, but a dramatic change in geopolitical circumstances could shift the balance of power. With the text of NAFTA 2.0 (USMCA) expected to come up for a vote in Mexico, the USA, and Canada’s legislatures later this year, there is a chance for the new government in Mexico and Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives to slow down the deal and deliver a coup. A bold stance on NAFTA 2.0 and mass mobilization against it could reorient North American trade, development, and climate policy in the critical years to come, and further, it would plant the seeds of the cross-border movement needed to topple the overwhelming power of fossil fuel multinationals.

Bringing Pemex back under state control is a core element of AMLO’s political project and remains an absolute necessity for any leftward political motion in Mexico. Decades of neglect threaten both the company and the country’s finances, and as corruption and violence have spiraled out of control, so has outright theft from Pemex. Reversing its current decline might reduce Mexico’s dependence on the U.S., but it will accelerate resource extraction like oil exploration and refinery production. AMLO’s ambition is to restore faith in public institutions in deep crisis, setting the stage for a deeper transformation.

During the oil crises of the 1970s, Pemex contributed as much as 80 per cent of the national budget. While today that figure is closer to one third, the President has called for shifting spending priorities to put “the poor first.” The government has limited salaries for highly paid senior officials, but it largely plans on raising Pemex’s revenues by increasing production.

Structural reforms to the energy sector over the years have restricted the government’s finances. For decades, Mexico’s political right-wing fought to privatize Pemex and finally gained traction with the rise of neoliberalism in Mexico in the 1980s. While other state enterprises were sold off, Pemex and the 1938 oil expropriation that created it were too popular for privatization to be politically viable. Instead, energy reforms worked incrementally to diminish Pemex’s investment in oil exploration and to gradually open the door to foreign capital. In 1986, the government began to allow private, foreign investment in petrochemicals, where Pemex had profitable and exclusive rights. In 1992 the company was broken up into subsidiaries, increasing administrative and borrowing costs. Reforms in 2006 and in 2013 opened the door to foreign investors to participate in direct oil exploration. High oil prices kept Pemex revenues up into the mid-2000s, but instead of funding new exploration to maintain or increase oil production, the neoliberal PRI and PAN governments of the last forty years moved money from Pemex to fund pet projects and pork barrel spending, all while imposing austerity on the people and risking the country’s finances.

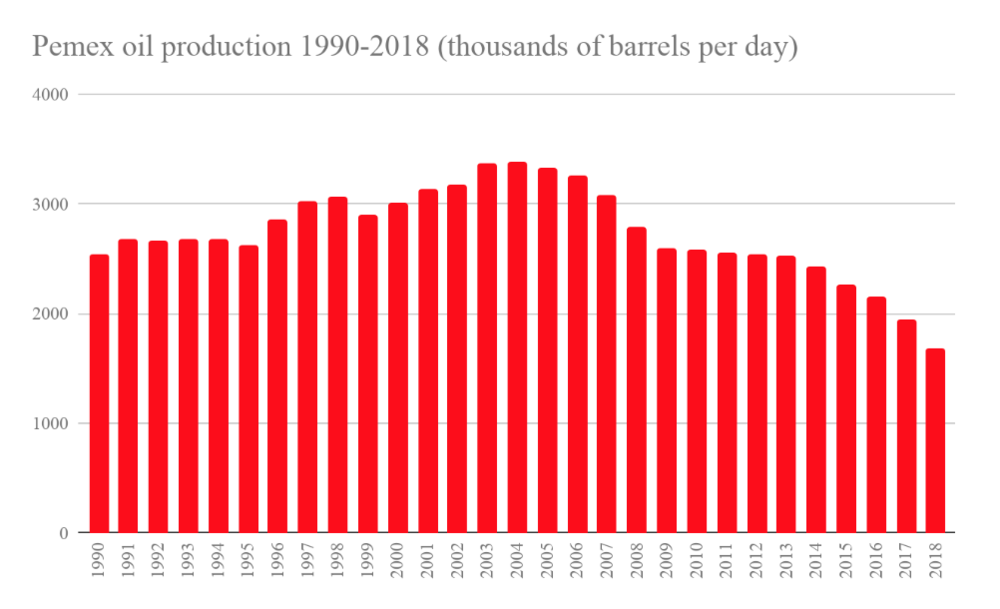

As a direct result of these policies, Pemex’s oil production peaked in 2004, and its daily production in 2018 was a third lower than it was three decades earlier, in 1990. With thieves siphoning off $3.4-billion worth of gasoline in 2018, the company’s dire financial situation and the state of its infrastructure has deteriorated significantly in recent years. Opening the door to private, foreign investment, a policy of underinvestment, and turning a blind eye to outright theft from within the company amounted to a deliberate plan to sabotage Pemex, paving the way to its inevitable privatization – a plan that AMLO has accused the past three presidents of tacitly, if not outrightly, supporting.

But is Pemex’s falling production good news for the climate? Not necessarily. Mexico has become even more dependent on U.S. fossil fuel companies in the process, with production shifting across the border. Despite being an oil exporter, Mexico imported almost 80 per cent of its gasoline last year, primarily from refineries in Texas and Louisiana. López Obrador likened the situation to “selling oranges and buying orange juice,” with prices on average a dollar more per gallon than in the USA. AMLO explicitly campaigned on eliminating gasoline imports within three years to end the situation. The new government moved quickly to increase Pemex’s 2019 budget, investing billions of dollars to refurbish its existing six refineries and in the construction of a new one. The budget projects for Pemex to increase crude oil production to 2.62 million barrels a day by the end of 2024.

The plan highlights the tension between the government’s goal of reducing Mexico’s dependence on the U.S. and its laudable environmental ambitions. Advocates have called the significant increase in spending on refineries a major red flag. Refineries are capital-intensive and polluting, and it can take decades to recoup the cost of the investment. Without policies that improve urban mobility, public transit, and long-distance travel, car ownership and demand for gasoline will continue to rise.

Putting a stop to rampant gasoline theft is also a factor in to the government’s plan to reassert control over Pemex, and raise revenues, and it is critical to its campaign to restore faith in public institutions. Around $10-billion (U.S.) worth of gasoline is believed to have been stolen over the last 10 years. In 2018 alone, estimates of Pemex’s losses to theft are as high as $3.4-billion. In late December, the new government shut down pipelines for repairs and deployed the military to guard infrastructure, resulting in long lines at gas stations across the country. Public support for the plan remains high as past presidents simply ignored the problem, letting it grow.

AMLO campaigned on fighting institutional corruption at all levels, and the likely masterminds behind the theft include public officials and high-ranking Pemex employees. Dissident members of the oil workers’ union STPRM have denounced their union president of 26 years, a former PRI senator who voted for Peña Nieto’s energy reforms, for his alleged complicity in gasoline theft. Another group of workers who claim to represent up to 10 per cent of the workforce have asked the government to decertify STPRM and recognize an alternative union in its place. These workers’ courageous acts, and the government’s vocal support for democratized unions, point toward the radical potential that re-nationalizing Pemex could unleash.

The Tlalhuelilpan pipeline explosion on January 18 captures the scale of gasoline theft in Mexico and reveals something about how widespread robbery of public resources has become. In a video taken minutes before the explosion, which killed nearly 100 people, crowds gather around the ruptured pipeline with jugs and buckets as gasoline gushes out of it. Perhaps these ordinary people soaking themselves in gasoline made a rational calculation: “If those at the very top are stealing from us, then we deserve our share.” But those at the very top will never have to pay with their lives.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Pemex’s slow-motion collapse has torn at the fabric of the social order. AMLO’s sweeping promise of a “fourth transformation” of the country – referencing Mexico’s historic independence, secular reforms, and revolution – calls for expanding social rights and restoring faith in battered public institutions. Rescuing Pemex is a critical step toward achieving those goals, but without raising the government’s ambition on climate mitigation, AMLO’s fourth transformation will fail to live up to its radical potential.

Prospects for Transformative Change

Across Latin America, neoliberals have waged analogous campaigns to deliver state-run energy companies like Argentina’s YPF, Brazil’s Petrobras, Petroperú and others into the hands of multinational oil giants. Venezuela’s PDVSA, with rights to the world’s largest proven reserves, remains a tantalizing prospect for vulture capitalists. Other ostensibly progressive governments have likewise fallen into the trap of funding social programs through resource extraction. In the long run, all oil companies must be shuttered in a rapid, just, and orderly way, but the multinationals that would take the place of these state-run companies under global capitalism are no better. Moves toward de-privatization reduce the power and reach of oil multinationals. They may set some of the conditions for a planned drawdown of fossil fuel extraction, which will require vast amounts of capital, but Mexico’s furtive efforts at de-privatization have yet to progress that far.

The AMLO government’s current emphasis on industrial development underlines its shortcomings on environmental justice. Its proposed “Maya train,” which would intensify tourist activity in the jungles of southeast Mexico, provoked a stinging declaration of resistance from the Zapatistas and allied indigenous groups. AMLO’s repeated overtures to patriotic capitalists should also invite skepticism from the left. The new government may be Mexico’s first left-leaning administration since the 1930’s, but its focus on development belies a greater continuity with the past than the government and its supporters may want to admit.

Though countries like Mexico export their natural resources on the global market, most consumption takes place in rich countries where the profits from resource extraction accumulate. Mexico is a sovereign country with the rights to extract its own oil and socialize those profits. There is no comparison between the scale of destruction perpetuated by the United States or any rich, industrialized country and developmental regimes in the Global South. Pemex produces less than 10 per cent as much as the entire U.S. oil industry, and its reserves are generally cheaper and less energy-intensive to extract from than unconventional oil fields in the U.S. and Canada, like the Bakken or Alberta Shale. Mexico should expand production in more rational and less environmentally damaging ways, limiting investment in refineries to refurbishing existing ones. Under ideal circumstances the government would use the capital Pemex accumulates from oil extraction to fund a transition away from fossil fuels. The critical question is under what internal and external conditions the Mexican state and actors from elected officials to oil workers might consider a planned drawdown of fossil fuels.

At present, Mexico is dependent on oil exports, buying gasoline from the U.S., and decades of privatization schemes have led to widespread theft of public resources. Strengthening public control over the energy sector has popular support, but for now, more radical measures such as de-carbonization are hardly on the radar. Where there is little internal pressure to take explicit steps to end fossil fuel extraction, one question to consider is how the AMLO government might attempt to reconfigure political and economic circumstances externally. NAFTA may be its opportunity.

This January 1 marked 25 years of North American political and economic integration under NAFTA and the 25-year anniversary of the Zapatista uprising, itself sparked by changes to Mexico’s constitution that privatized indigenous land when NAFTA took effect. AMLO’s government has shown itself willing to push during NAFTA 2.0 talks. Before taking office, the presidential transition team negotiated the removal of restrictions on Mexico’s energy sovereignty from the deal. The USA, Mexico, and Canada’s legislatures must approve the text of NAFTA 2.0 before it comes into effect, meaning any one of them has the power to put the deal on hold. Climate activists in the U.S. can turn up the pressure on House Democrats, who vote on the text of the deal first, demanding they halt the deal and renegotiate under a new, hopefully progressive president. It has happened before. In 2008, Nancy Pelosi torpedoed George Bush’s free trade deal with Colombia, bringing it back for a vote with revised labour standards in 2010. A unified front against NAFTA 2.0 would essentially match President Trump against Speaker Pelosi and AMLO, and the obvious victors would have the power to radically rewrite the trade policies governing a third of the global economy. One idea for the bargaining table: the U.S. and Canada must initiate a planned drawdown from fossil fuels first and commit funding to less wealthy countries for their transition.

As GM workers in Detroit picketed the North American Autoshow demanding a Green New Deal, 70,000 auto parts workers were on strike demanding higher wages in the border city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas. Overcoming the adverse conditions global capitalism imposes on left-wing governments in the Western Hemisphere and across the Global South will be impossible without organizing beyond borders rooted in common struggles at home. As climate activists build closer bonds with the labour movement, the prospect of fighting for just transition policies within the framework of NAFTA renegotiation could build a stronger labour-climate coalition and powerful cross-border coalitions to boot. A truly just Green New Deal must upend the perverse dynamics of development and resource extraction that keep some countries subjugated all to maintain the USA’s standard of living.

With Pemex back under public control, the AMLO government plans to fund expanded social rights and fight corruption. It will reduce its dependence on the U.S. and resist the power of fossil fuel multinationals. But without a dramatic change in its external conditions, led by the government or from below, Mexico and North America as a whole may never realize an energy transformation. •

This article first published on The Trouble website.