GM Oshawa: Making Hope Possible

The once unimaginable – the end of GM Oshawa – seems on the verge of becoming the new reality. If there is any lesson to be learned here it is that overturning this imposed reality can’t be achieved by traditional protest and traditional alternatives. Continuing our dependence on unaccountable corporations, offering subsidies and concessions without means to enforce job guarantees, making competitiveness the only test of worthwhile activity, looking to ‘better’ free trade agreements and so on, are dead ends. All they offer is more of the same: death by a thousand cuts.

Imagining a radically different and more democratic approach based on community and national planning – opening the door to the formerly unthinkable – may, as overwhelmingly ambitious as that may seem, be the only option with any chance of success.

On November 26, 2018, General Motors (GM) announced that the Oshawa Assembly plant, once the largest auto complex in North America, will no longer exist. In the 1970s, the site included three massive assembly plants that turned out 3,000 vehicles daily. Other GM plants in the city made batteries, radios, radiators and axles. A host of independent component plants with their own special capacities, spread across the city and nearby localities. At the end of the 1970s, GM had some 23,000 plant and office workers in Oshawa. At the time of GM’s latest death notice, over 85% of those jobs had already vanished, leaving 3,000 workers desperate to hang on to the one remaining GM operation in the city.

Workers as ‘Collateral Damage’

Given that history, there were few periods in recent years when there weren’t rumors of an imminent closure. In the months before the axe came down on the last plant, those rumors had taken on a new, darker, urgency. The news came confirming those fears may not have been a complete surprise, but that didn’t make it any less devastating. One question predominated: if GM’s profits were restored, and if GM Oshawa had for years ranked first or second in quality and productivity among all the assembly plants on the continent, why would Oshawa be given up on as a site of vehicle assemblies?

The experience of the past few decades suggests the general dilemma of working class life under capitalism: no matter what workers do, how good their work, how restrained their demands, and how much they accept in terms of work pressures, they will always remain vulnerable in a system geared to profits, competition and the priorities of stockholders and senior executives. There will always be someplace cheaper to run to, and as corporations restructure to address technological and market changes, workers are treated as little more than ‘collateral damage’.

In the case of the industry today, GM – like Ford and Chrysler (Fiat) – had concluded that assembling cars in the USA or Canada provides too small a profit margin and so such work will be moved elsewhere. Though truck production is environmentally harmful and will eventually be checked by the reality of the ecological crisis, the companies see the present as a time to make as much money as they can before that change is imposed. And though electric cars will come, they are still a way off; and when they do come, the companies are set on building them, like regular cars, wherever it is most profitable to do so. (China, it’s worth noting, has been accelerating its commitment to electric cars and, though still a small fraction of Chinese car sales overall, the Chinese market for electric cars is currently some three times that of the U.S. and Canada put together and growing much faster.)

Under the above scenario the Oshawa plant, which assembles a mix of both cars and trucks, was doomed. With car assembly being phased out in Canada and the USA, there would be no new car assembly work, leaving a good part of the plant idle. And since the truck production was overflow production – work that Oshawa only did when sister U.S. plants were operating at maximum – that work could be consolidated in U.S. plants as the market flattened out (which it is now in fact doing). From GM’s perspective, Oshawa was redundant.

There’s another factor that can’t be ignored. With car production being phased out in the two countries and the slowdown in truck sales expected to continue, GM had excess capacity. If five or more plants were to be permanently closed, U.S. politics dictated that not all the closures could be in the USA. This would likely have been the case even before Donald Trump became President, but it was especially so in the context of Trump’s bravado election promises of bringing jobs back to the USA. With closures in Mexico excluded because that is where car production will be concentrated, Canada could not escape having at least one major plant closed. Oshawa was the chosen victim.

GM waited until the new trade agreement was signed before making its announcement. Though the industry’s longer term strategy for current car plants and the electric car were well known at the time of the trade negotiations of the new United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) to replace NAFTA, nothing in the eventual agreement prevented GM from moving to close factories in the U.S. (or Canada) while Mexican plants stayed open. Before the ink was dry on the new trade agreement, President Trump’s declaration that this was ‘a great deal’ that would lead to ‘manufacturing many more cars’ in the U.S., was exposed for the sham it was. So, too, was Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s hollow prediction that the trade agreement would bring ‘stability’ for Canadian autoworkers, their families and their communities.

Lame Politicians

It might have been assumed that the Federal and Ontario governments would, even for narrow political reasons, aggressively insist that GM owes Canada a new model. After all, in addition to GM reaping especially high profits in Canada over the years, Canada had significantly contributed to bailing GM out during the financial crisis of a decade ago. Some $3-billion of that aid was never recovered and simply written off. But publicly chastising corporate behavior isn’t how our elected leaders (or capitalist states, for that matter) generally relate to corporations and especially to American business.

The response of the Trudeau Liberals was a feeble expression of ‘disappointment’ in GM’s blow to Canadian manufacturing, and a limp offer of more training for comparable jobs that don’t exist (something formerly laid-off GM workers know too well). If there were expectations of a more forceful response from the new Premier of Ontario, Doug Ford, who came to office promising to speak for ‘the little guy’, this too was quickly put to rest.

The Premier seemed too preoccupied with putting up giant billboards declaring that ‘Ontario is Open for Business’ to notice that one of the key manufacturing facilities in the province was going the other way. Ford offered not the slightest criticism of GM, but rather rushed to pronounce that nothing could be done: the “ship has sailed.” Like the federal government, the Ontario government’s prime concern was to make the controversy over Oshawa’s closing disappear as soon as possible so no one would ask embarrassing questions about what our political leaders were doing to protect us.

Ford’s response has been all the more hypocritical and revealing because of the contrast with his instant and determined commitment to reduce, as soon as he took office, regulations on business that impacted on worker safety and on product quality, as well as to undo legislation that provided a further increase in the minimum wage and erase labour legislation that modestly supported the right of workers to form a union and receive more paid sick days. And even though Toronto was well into a municipal election, Ford arbitrarily interrupted the ‘sailing’ of this ship and changed the terms of the election, cutting the number of councilors in half, damaging effective democracy in the city, and stunningly calling on the rarely-used “notwithstanding clause” in the Canadian constitution to block opposition. For the Premier of Ontario, some things are apparently reversible and worth dramatic action, others are not.

In the U.S., Trump did at least direct some anger at GM. But as with his Canadian counterparts he has so far not offered much more, distracted by the conflict with China. The criticisms of China, it’s worth noting, had evolved into a concern with removing Chinese demands that U.S. companies share their technology as the price of entry into the Chinese market and barring China from certain sensitive new technologies – neither of which spoke to the manufacturing jobs in the Mid-West that Trump had once ranted about. His current anger, it’s fair to guess, is less about the impact of GM’s closures on workers than the egg on his face brought on by the GM closures and his fading credibility in reversing the decline in U.S. manufacturing jobs.

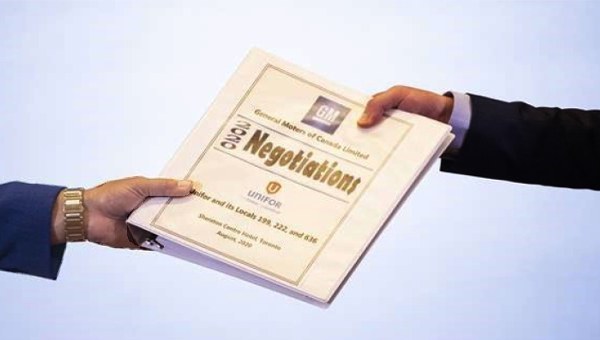

The Union

The Unifor leadership has its own actions to answer for. It had sold the last agreement on the basis of a firm ‘guarantee’ of a new model, a model that it now is asking for again. In the 1980s and 1990s, the Canadian union had criticized its American parent, the UAW, for such trade-offs, arguing that concessions would not save current or future jobs. That position proved all too true. Between 1979 and the present, the UAW settled every agreement with an alleged guarantee of job security while the number of UAW members at GM went from 450,000 to a level of only 50,000 today.

To have ignored this experience was not only a fateful mistake but the particular concessions made – the institutionalization of two-tier wages and pensions within the workplace – critically divided the workers and weakened the union. In addition, Unifor’s leadership celebrated the new trade agreement as an imperfect, but very positive, advance for Canada’s auto industry. That celebration now seems rather ill-timed when it was followed, as noted earlier, by GM demonstrating that the agreement posed no effective limits on what auto companies could do within its rules.

Nevertheless, the union is expressing the anger and frustrations of the workers. It has been working to mobilize opposition, and has proposed possible solutions. If there is any hope for Oshawa, it rests on what the union – and especially the workers – will do.

Searching for Alternatives

The goal of the union is get the new model in Oshawa that it was promised in bargaining. The pressure for doing so lies in mobilizing public opinion and possibly pressuring GM through boycotts and calling on the Federal government to place high tariffs on the import of GM cars from Mexico. While there is good reason to support the union’s orientation and be sympathetic toward anything that makes GM pay a penalty, the strategy of the union as it now stands has significant limits.

Consumer boycotts look to gain support from individual, unorganized consumers rather than the actions of organized workers. Their impact is generally marginal and not sustained. They have only worked in very narrow circumstances: boycotting a local business, or in support of a mass movement for social justice, like the opposition to South African apartheid. And even in the latter case, the impact of the boycott was primarily by way of large institutions such as union or university pension funds, not the actions of individual consumers.

As important as the Oshawa closure is for the workers directly affected, closures are too common a part of the landscape for any one closure to be treated as exceptional. Mineworkers, steelworkers, and even autoworkers have seen hundreds of major workplaces closed without boycotts being called. In auto, for example, there was no boycott called when Quebec lost its only assembly plant, or when the London area lost its sole assembly plant, or when Oshawa’s own truck plant was closed in 2009. Moreover, with even GM workers in Ingersol and St. Catharines likely divided on a boycott because of concerns with their own security, it would make it all the harder to spread support elsewhere.

As for tariffs on Mexican cars, this seems a strange demand coming on the heels of the just-signed free trade agreement which the Unifor leadership enthusiastically supported. In any case, Canada could not introduce such tariffs without leaving the new trade agreement. There may be a case for ending the new trade agreement, but exiting it because of auto alone is a non-starter – it would depend on a much larger consensus across the country about challenging Canada’s relationship to not just Mexico but especially the USA. And even if Canada did impose tariffs on Mexican cars, it is not at all obvious that GM would respond by moving a model out of Mexico. And if it did, that it would come to Oshawa rather than to a U.S. plant (and then shipped to Canada from there).

The point is that the chances of giving Oshawa another model are slim and there is no effective mechanism to force GM to do so, especially while it is closing U.S. plants. Workers could do what other workers have done in the face of a closure and occupy the plant. Such occupations serve to keep the closure in the limelight and that is important, but this doesn’t answer the question of what to do with an assembly plant that GM doesn’t want. Without some plan, an occupation doesn’t get beyond being a protest; in itself it does not lead to an alternative.

What about of a direct government partnership with GM to build an electric car? This has the advantage of looking ahead, but the context is that the Ford government in Ontario has abandoned any policy to support the growth of electric vehicles and for its part, GM has made it clear that at this point in time it is not interested. And even if it were, it would still leave us vulnerable to GM pulling out, as it has repeatedly done (even after it blackmailed governments into subsidizing it). Attracting another private investor to build an electric car is also not a solution. As Unifor’s president, Jerry Dias, has noted, there is not yet a mass market for electric cars and even if the new owner was competitive, the potential workers employed would only occupy a fraction of the Oshawa plant.

Gord Wilson, the former Director of Education for the union (in the old CAW) and also former President of the Ontario Federation of Labour has gone further and argued for the revival of a notion hotly debated among autoworkers in the 1960s: a publicly-owned Canadian-built car. Nationalizing the Oshawa facility to assemble such a facility has the merit of moving away from dependence on companies like GM. It also opens the possibility of gradually shifting to an electric car as the market for the latter expands.

Yet it also raises the constraints involved if this is to occur on the terrain of open international competition. Starting from scratch (the Oshawa plant offers only an assembly capacity), such a car could not be expected to compete with the other companies already in the industry and this could not be overcome by appeals to ‘buy Canadian’. On the other hand, closing our market to other companies so the Canadian car could survive would come up against fears of U.S. retaliation from other workers – including other auto workers at Ford, Chrysler and component plants.

Plan B

All this points to a stark choice. Either we hang on to the simplest solution and stubbornly insist that GM give Oshawa a new model or we need a plan that requires us to think beyond GM, beyond the auto industry and beyond Oshawa. If it turns out that getting a new model is simply not on, then the only fallback, a Plan B, is a far more ambitious project that includes the Oshawa plant, but also speaks to broader sectors and regions of the economy and to far broader needs.

That is, we need a project that breaks from the current road to nowhere and which can capture the imagination of working class communities across the country. Such a project could include private businesses but would stand outside of a future based on the destructive criteria of competition and profit maximization and would address new and existing needs in a planned way. Ironically, the bind we are in makes such larger, more radical aspirations the only practical way out.

The starting point lies in combatting the risk of this fight for jobs fading away, as has happened with other similar struggles. GM will likely offer one-time pension top-ups and buy-outs that will be seductive, especially for those near retirement. As time takes its toll, others may find this enticing. This will be a crucial test for the union. Giving in to a trade-off the GM jobs for money will leave the city with a dramatic loss of high-skill, unionized jobs and leave many union members in the related parts sector in the lurch. And it will reinforce the confidence of other companies (in all sectors) to close workplaces at will.

Addressing this means a constant dialogue with the workers in the plant: setting up subcommittees to engage workers in on-going discussions of alternatives and tactics and to mobilize among other plants and in the community, developing a regular newsletter to keep the workers updated and to neutralize company and business propaganda against a fightback. It may also demand periodic industrial actions (interruptions in production) that are undertaken, not simply to let off steam, but to remind the public and politicians – and the workers themselves – of what is at stake and to demonstrate their readiness to fight for a different and better future.

Second, given GM’s disinterest in sustaining the Oshawa plant, the facility and its equipment should be placed under public ownership with no further compensation – the plant and its equipment have already been paid for by the sweat of workers and the $3-billion in unpaid subsidies from taxpayers. Expropriating GM will require mobilizing public support, and committees should be set up to organize and mobilize the community. Might, for example, workers declare days of action during which when workers don’t go to work – aided perhaps by retiree picket lines or ones organized by local supporters – and instead go door to door to explain their case for challenging what happens to the Oshawa facility?

Since the government is unlikely to step in until the workers have forced their hand, placing the plant under public ownership will especially mean standing ready to block GM from taking its equipment out – by occupying the plant if necessary and reinforcing that occupation with supporters outside the plant gates. The autoworkers union was born out of the sit-down strikes in the desperate days of the Great Depression and a similar action in today’s desperate times might now have a role in reviving the union.

Third, there must be a plan of what to do with the plant. During the Second World War, GM stopped making cars and was converted to producing military vehicles and airplanes. When the war was over, the plants were reconverted again over a period of 18 months. Is there an equivalent to thinking in such grand conversion terms today? (See The New Lucas Plan.) If the environmental crisis is identified as the major social challenge of the rest of the century, and this implies that everything about how we produce and live will have to be changed, then that suggests the ‘peaceful war’ we might now wage.

This would involve: (a) cataloguing all the potential equipment and goods needed to support the environmental makeover of society; (b) cataloguing the rich knowledge, skills and tools we currently have or would need to manufacture the goods and equipment for the environmental reconstruction; and (c) establishing a structure that could monitor, with the help of workplace committees, whether plants are getting the investment they need or threatened with closure – and then stand ready to ensure Canada doesn’t lose valuable productive capacities.

Among the environmental changes that will demand manufacturing and other jobs are rebuilding neglected infrastructures and supplying the related equipment; expanding telecommunication networks; transforming how we get our energy (such as the expansion of solar panels and wind turbines); addressing the range of transit systems (from electric cars to electric delivery vehicles to mass transit); revamping household appliances; refurbishing of homes and offices to limit energy waste; reconfiguring motors and machinery used in factories. Moreover, as we list these potentials, we can also ask what potentials there are in responding to the expanding needs of an aging population (e.g. hospital equipment, diabetic monitoring equipment, wheel chairs), and also raise whether some of what we currently import could be made locally.

The lists of expertise we currently have and could adapt would include investigating what our aerospace sector, with its special work on engines and propulsion systems, has to offer; the varieties of steel products steelmakers could provide; the tool and die capacities in the economy; the flexibility of current component shops to meet new demands; the design and engineering capacities in the private sector and universities; the research being done in government scientific labs; and what training, retraining or entirely new capacities needed to be developed (in this case for actual jobs).

If, after the financial crisis, when hundreds of plants were shuttered we actually had some kind of plan in place and were ready to save some of those plants and capacities, we would today have a structure for also thinking more concretely where the Oshawa plant and its suppliers might fit in.

Conclusion: Is This Really Feasible?

We can’t say if this is feasible. The direction outlined above has to be considered a long shot. But thinking small means that in every crisis we look around and conclude there are no options and so need to accept what is on offer. Experimenting with something that might work and is oriented to our needs and using and further developing our skills and knowledge brings a measure of dignity to what we are doing and opens the door to doing something constructive now that can expand our options in the future.

All this is of course not so much a technical question as a political one. Unless we can inspire some broad support, none of our plans matter. An organizing mantra is that if you want to get people on side, don’t come to them just with your own problem; raise a joint dilemma that you can work on together. Thinking bigger can inspire hope in others and build a collective project within which particular interests, like that of the Oshawa plant can fit.

Finally, all those who sell their labour – and a good many beyond that – have suffered from the declining strength and social relevance of the labour movement over the past few decades. This won’t be easily corrected. But thinking outside the box, engaging in larger struggles and actively involving our members in the discussions and strategizing over what to do and how to do it, carries the promise – or at least the potential – to revive our movement. There is no other way to overcome the demoralization of so many of our members, move to set aside the destructive divisions between unions that are such a barrier, and play the kind of social role that can excite a new generation of leaders and activists. •