Why Canadian Prisoners Are Participating in the U.S. Prison Strike

Prisoners are once again on strike. Since August 21, prisoners have been engaging in various forms of protest in at least ten states. And prisoners in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, have also joined the protest wave, issuing their own statement and set of demands.

While the strike has provoked heavy-handed responses by some prison administrations, it is too early to tell if the strike will be able to force concessions. The U.S. prison system is often characterized as uniquely unjust – which it admittedly is in key ways. So, why have Canadian prisoners risked participating in a U.S.-based strike movement?

In the words of the prisoners themselves, “The organizers of this protest assert that we are being warehoused as inmates, not treated as human beings. We have tried through other means including complaint, conversation, negotiation, petitions, and other official and non-official means to improve our conditions.”

At this point the size and character of the U.S. carceral state is well known: the U.S. has the largest prison population is the world, and it has one of the world’s highest incarceration rates. And the racial disparity evident in the U.S. prison system is staggering.

Added to this are issues related to private prisons, the exploitation of prison labour by private firms, and a myriad of other issues, that culminate into a punitive, revanchist, and oppressive correctional system. While the size of the U.S. prison system makes for difficult comparisons, many of its other issues do not. As the striking prisoners at the Central Nova Scotia Correctional Facility, also known as “Burnside jail,” are demonstrating, much of the critique of the U.S. prison system resonates with Canadian prisoners.

While the participation of the Burnside strikers in this latest U.S.-based prison protest wave is unique, protest by Canadian prisoners is not – prisoners in Canada have their own long history of struggle against the injustices of the system in which they are confined.

The Canadian Carceral State

The Canadian prison system – which includes the country’s immigrant detention regime as well as the federal and various provincial correctional systems – is plainly awful. Canada is one of only a few countries that indefinitely detains immigrants, a practice decried by the UN. While recent anti-Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) protests in the U.S. have drawn attention to the detention of immigrant children, much less has been paid to the fact that Canada also detains migrant children, some of them “unaccompanied.” For years, immigrant detainees in Ontario have drawn attention to the problems of the country’s immigration system and the conditions of their confinement by engaging in intermittent hunger strikes.

Canada’s incarceration rate is around 118 per 100,000 people. While this is significantly lower than that of the United States, it remains higher than most Western European liberal democracies. It’s also notable that this rate is close to that of the United States in the early 1970s, at the height of the prisoners’ rights movement. Although it’s hardly insignificant, the size of a prison system should not be the determining metric of its efficacy or character.

In its latest annual report, the Office of the Correctional Investigator, Canada’s federal prison watchdog, identified a host of issues in the federal system including deficiencies in health care provision, especially in relation to mental health; low pay and high expenses; and lack of effective educational, vocational, and rehabilitative programming, as major issues facing Canadian corrections. While the annual report of the Correctional Investigator is helpful in understanding the nitty-gritty of the problems in the country’s prisons, it rarely spurs a meaningful government response.

Like the USA, racial disparity is also evident in Canadian prisons, with indigenous people in particular being hugely overrepresented. Indigenous people make up about 5 percent of the population, but account for around 27 percent of federally incarcerated adults. This trend is even more disturbing in Canada’s women’s prisons, where indigenous women account for 38 percent of the prison population. The youth justice system is even worse – nearly half of incarcerated youth in Canada are indigenous. These rates of incarceration have caused some commentators to assert that Canada’s prisons are its new residential schools. Black Canadians are also vastly overrepresented in Canada’s prisons and jails. Only 3 percent of the general population, Black Canadians account for 10 percent of the federal prison population.

Canada’s prisons shouldn’t be understood simply as instruments of racial dominance – they also warehouse the country’s poor and mentally ill. A 2010 study by the John Howard Society of Toronto of provincial prisoners in the Greater Toronto Area found that one in five were homeless at the time of their incarceration. Half of men entering federal prisons are identified as having “Alcohol or Substance Use Disorders.” and over 40 percent of sentenced prisoners and those remanded into pretrial custody are unemployed at the time of their admission. The 2016 Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator states that “federal prisons now house some of the largest concentrations of people with mental health conditions in the country.”

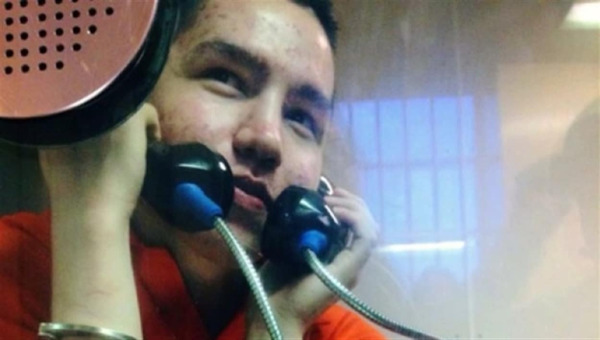

The consequence of these issues can sometimes be fatal. Several high-profile deaths have triggered inquiries, such as that of Ashley Smith, a young mentally ill woman who hung herself in 2007, in full view of guards who were ordered not to intervene until she lost consciousness. In a 2015 case, Matthew Hines died after a “use of force incident” with guards. Initially, Corrections Canada told Hines’s family that he had died of a seizure after being found “in need of medical attention.” It was later revealed that he had been beaten, restrained, and pepper sprayed by guards. Ten guards then placed him, handcuffed and with his t-shirt over his head, in a decontamination shower where he fell and hit his head. A video taken by prison staff shows Hines, laying on the shower floor pleading to officers that he couldn’t breathe: “Please, please … I’m begging you, I’m begging you.” The incident resulted in charges being laid against two of the officers involved. In April of this year, both of the accused officers entered not-guilty pleas.

Meanwhile, prison walls haven’t been a barrier to Canada’s escalating overdose crisis. Rates of drug-related deaths doubled in federal prisons between 2010–2016. Due to variations in data collection, it is difficult to tally overdose deaths in Provincial jails, but it is likely that the numbers are even higher. In 2017, twenty-seven prisoners died of overdoses in Ontario’s jails alone.

Provincial prisons, like the one in Halifax, are notorious for their poor conditions – something so widely accepted that upon conviction, judges routinely reduce sentences for time-served in pre-trial detention. Staff shortages plague jails, commonly resulting in lockdowns. Solitary confinement – despite its tendency to cause and exacerbate mental illness – is used frequently and with little regulation. The tragic case of Adam Capay, a young First Nations man awaiting trial in the Thunder Bay Jail, caused national controversy in 2016 when it was discovered that he had spent fifty-two months in solitary confinement in a Plexiglas cell, lit twenty-four hours a day.

The United Nations has declared that more than fifteen consecutive days in solitary confinement constitutes torture. The case only came to the attention of the press and Provincial correctional officials after a guard – the president of his union local – requested that Ontario’s chief human-rights commissioner look into Capay’s conditions, set off a review of solitary confinement in Ontario, and prompted federal rule changes.

Burnside has faced many of these issues including overcrowding, fatal overdoses, prisoner-on-prisoner violence, over-reliance on solitary confinement, and staff shortages that result in routine lockdowns. These issues are reflected in the demands of the prisoners striking at Burnside.

Resistance and Prisoner Protest in Canada

The striking prisoners in Burnside acknowledge that they are far from the first in the country to protest, stating “we recognize the roots of this struggle in a common history of struggle and liberation.” Indeed, Canadian prisoners have a long history of collective resistance against inhumane conditions and treatment. Sometimes this resistance has taken the form of hostage-takings and large-scale riots – such as the deadly ones at Kingston Penitentiary in 1971, British Columbia Penitentiary in 1975, and Archambault Penitentiary in 1982. However, there is another, less-examined history of nonviolent collective actions by prisoners, including sit-down protests, work stoppages, and hunger strikes. As is made clear in their statement, this is the history in which the prisoners at Burnside are situating themselves.

The history of prisoner work stoppages stretches back to pre-Confederation, and although prisoner protests often failed or resulted in only minor improvements, they sometimes had more significant and longer lasting results. In September 1934, striking prisoners in BC demanded wages for prison work. The strike escalated into a minor riot that saw some property destruction and ended with protest leaders rounded up to face corporal punishment. Despite the successful repression of the protest, the demands for wages were won. At the beginning of January 1935, federal prisoners who worked began receiving a five-cent-per-day stipend.

The 1970s were turbulent times in Canadian prisons. One of the longest prison strikes in Canadian history started on January 14, 1976, when 350 prisoners at the Archambault Institution in Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines, Quebec, began a work strike. The prisoners declared their solidarity with striking prisoners at St Vincent de Paul Penitentiary in Laval and demanded better conditions. The Archambault strike lasted 110 days. Although the action was primarily a nonviolent work stoppage, there was considerable violence over the course of the protest. Prisoners were beaten by guards and prisoner-strike breakers, and two guards were jumped by strikers. Most spectacularly, a month after the strike began, two former St Vincent de Paul prisoners blew themselves up in an attempted bombing of a bus station in support of the Archambault strikers. Having been granted several of their demands, including recognition of a prisoners’ committee, the prisoners ended the strike. The next year, the prisoners’ key demand – the right to physical contact with visitors – was made policy by prison officials.

In the fall of 2013, Canada saw a nearly unprecedented strike in the federal system when prisoners stopped working their manufacturing, textile, construction, and service jobs to protest a 30 percent cut to their wages and the elimination of pay incentives offered by CORCAN, the government agency responsible for coordinating and managing prison industries. While unsuccessful at reversing these cuts, the strike demonstrated prisoners’ ability to coordinate protests across the country. Since that time there have been numerous smaller scale protests, hunger strikes, and work stoppages at various federal and provincial institutions across Canada.

Canadian prisoners – like others around the world – have also attempted to organize unions, to advance both their interests in relation to the conditions of their incarceration, and those of their labour within the institution. In 1975, The Prisoners’ Union Committee, an organization of former prisoners and radicals who had cut their teeth in the anti-war and women’s movements, and supported by the American Indian Movement, attempted to represent prisoners who were engaging in escalating work strikes and sit-down protests in the provinces of British Columbia and Ontario. The effort was unsuccessful, but resulted in the creation of Prisoners’ Justice Day, an annual day of work and hunger strikes initiated in 1975 and held every August 10 since. The date of the first Prisoners’ Justice Day was chosen to commemorate the anniversary of the death of Edward Nolan, a prison organizer who died by suicide in his solitary cell in Millhaven Institution in Bath, Ontario. The event continues to serve as an annual day of remembrance of those who have died in Canada’s prisons.

In 1977, prisoners working in a privately run meatpacking plant operating out of the provincial jail in Guelph, Ontario successfully organized a local of the Canadian Food and Allied Workers Union, along with their non-incarcerated coworkers. In doing so, they became the first group of prisoners to be covered by a legally recognized collective agreement in North America. Their unionization resulted in the equalization of pay between prisoners and non-prisoners, among other benefits.

Most recently, in 2011, the Canadian Prisoners’ Labour Confederation (or “ConFederation”) began organizing around working conditions and pay in the Mountain Institution in Agassiz, British Columbia, with the goal of winning union recognition for federal prisoners. The effort fizzled after successive labour boards refused to adjudicate the case, ruling that federal prisoners fell outside of their jurisdiction and that they were not “employees,” but participants in rehabilitation programs.

Prison Justice Everywhere

Canada incarcerates too many people, and especially too many black and indigenous people. It routinely treats those it incarcerates as less than human, and overwhelmingly fails in its mission to deter crime and rehabilitate “offenders.” American progressives often – incorrectly – idolize Canada. Reducing the U.S. incarceration rate to one similar to Canada’s would clearly be an accomplishment for human rights and social justice; it won’t, however, necessarily address the plethora of issues endemic to prison systems, including Canada’s. The demands of the strikers in Burnside makes this clear. Any movement for social, racial, and economic justice in Canada, like the USA, will have to confront these issues and support prisoners in their struggles.

In response to the demands of the Burnside strikers, Jason MacLean, correctional officer and president of the Nova Scotia Government and General Employees Union – which represents workers at the jail – supported the prisoners’ demands to better food, a better library, and improved air quality. He was less supportive on other issues such as contact visitation rights, access to personal clothing, and improved exercise equipment. Most critically – and disappointingly – MacLean has dismissed the prisoners’ demands for improved medical care as unrealistic:

“I think everybody has a right to health care. We should all have better health care. I would make the argument that those that are incarcerated have access to better health care than most Nova Scotians do.

“I see what they’re saying, that they want to have more access, but that’s a hard thing, I believe, to sell to the public of Nova Scotia considering hardly anyone has a doctor anymore, and the acuity level of people in care who are being pushed out of hospitals as well.”

While it’s critical that prisoners have real and substantive access to quality health care, MacLean touches on a point that shouldn’t be dismissed. Prison conditions can only practically be “improved” relative to the general conditions of society. In his 1980 book Prisons in Turmoil, the groundbreaking convict criminologist and former organizer of the California Prisoners’ Union, John Irwin, makes this argument succinctly: “any help offered to prisoners must be available to free persons.” As long as the general public lacks access to quality health care, education, housing, recreation, and other services, it should be unsurprising when such services offered in prison come under attack. Pioneering Canadian prisoners’ rights activist Claire Culhane puts it more poetically: “We can’t change prisons without changing society. We know that this is a long and dangerous struggle. But the more who are involved in it, the less dangerous and the more possible it will be.” •

This article first published on the Jacobinmag.com website.