Obrador and Mexico’s Watershed Election

Uncertainties, Contradictions and Struggle

The July 1 national election in Mexico is likely to be a watershed in Mexican history. The splintering of the three old parties, their unprincipled tactical electoral alliances across party boundaries, the rapid movement of key party figures from one party to another, have made understanding the labyrinth of Mexican elections even more complex and confusing than ever.

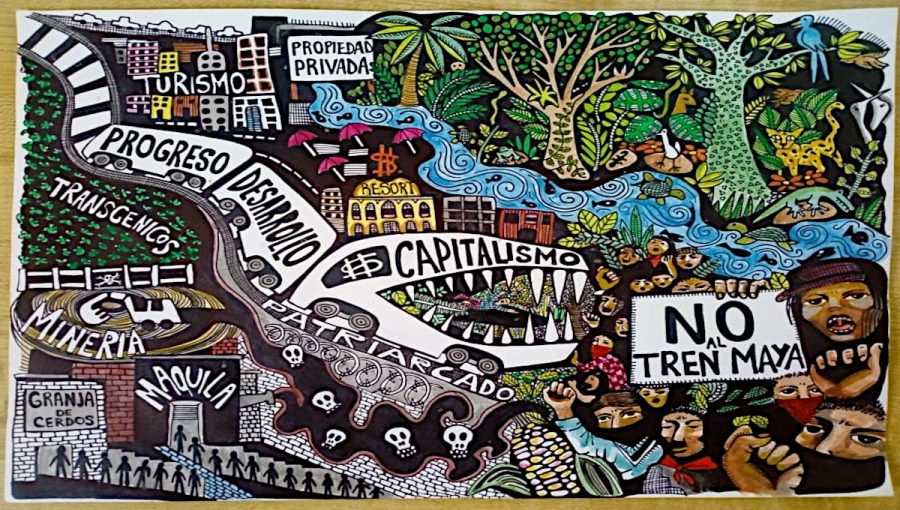

The possibilities of a victory by Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), under the rubric of his Morena party, is strongly opposed by most of big business, and needs to be seen in the context of Mexico’s long-term crises-ridden transition toward a not-at-all clear destiny. The destiny promoted by Mexican, Canadian and U.S. big business and political elites has been that of continental integration within the framework of NAFTA, as part of a neoliberal domestic transformation; a decimation of labour and social rights within Mexico and an extensive market-led regime of accumulation (appropriation of the commons – oil, minerals, land, and public goods); all legitimated by electoral pluralism safely contained within the bounds of the neoliberal project. This continentalist and globalist perspective is under stress in the U.S. from the hard right nationalist politics of President Donald Trump, although big business in all three countries remains firmly committed to it.

The election is taking place in the context of this set of interrelated crises that is both contributing to the support of an outsider and will also contribute mightily to the dilemmas and challenges that his government would face, if elected. They include a deep fiscal crisis of the state, an economy in long-term crisis, a deeply corrupt state apparatus, and continuing wars within the state-drug cartels complex. They are further confounded by the xenophobic assault on Mexican immigrants by the U.S. government; the possible crisis from U.S. imposed tariffs, potential problems stemming from the renegotiation of NAFTA; and an unpredictable and racist U.S. President. But it is the deep fiscal crisis that will shape the immediate dilemmas and underlying contradictions and ambiguities in the AMLO program and within his diverse set of allies and base of support. All these dilemmas and contradictions would come to the fore in the event of an AMLO victory which itself would greatly raise popular hopes and expectations.

Elections and the Discontents of the Popular Sectors

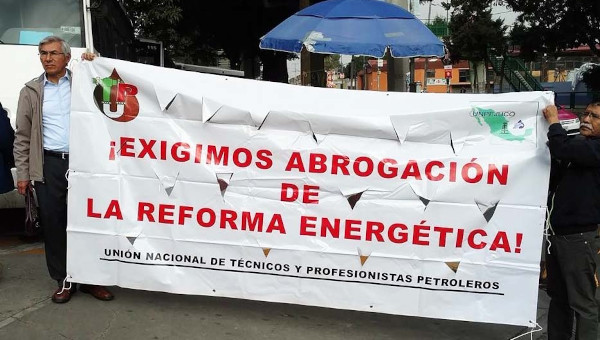

The rapacious neoliberal transition has generated significant and ongoing opposition from popular sectors in Mexico through strong, though fragmented, protest movements (e.g., local communities, both indigenous and non-indigenous, against mining and capitalist mega-projects, teachers against big business promoted transformation of education). The massive discontent against ongoing corruption, endless human rights violations, growing inequality, and the destruction of public services has also expressed itself electorally.

Almost every six years since 1988, the national elections have been the venue for popular expression of discontent, an expression that has been perceived by big business and the political elites as a threat to the neoliberal project. National elections provide a moment in which popular discontent, generally fragmented, can find a unifying direction and hope, albeit that common thrust can remain plebiscitarian in the absence of the development of popular organization and empowerment from below that go beyond the discrete moment of voting. Nevertheless, Mexican and continental big business and political elites have felt threatened by the prospect of a President from outside the bounds of their shared project. This was expressed in the presidential electoral frauds of 1988 and 2006 and the immense corruption of the 2012 election, the last two both involving successful attempts to block AMLO, the current front runner, from ascending to the Presidency.

A key aspect of the old system of Bonapartist domination was that the capitalist class was kept at a distance from direct political power even as political elites trickled or stormed into the capitalist class through cronyism and corruption. This system – which lasted over 70 years – was anchored in a post-revolution policy of state-guided capitalist development and the subordinate integration of the working class, peasants and middle sectors in the historic bloc and ruling party. This integration was organizational and rhetorical and included material concessions to strategic sectors. As well, the government systematically sustained the hopes for access to the material gains of inclusion of those still on the outside.

The “democratic transition,” pushed for by the ‘middle-classes’ and popular forces was hijacked by big Mexican capital whose wealth and power had grown during the period of statist development. They were happy with the subsidies and protection that the state provided but unhappy with the degree of autonomy of the government, a degree of autonomy demonstrated by the sudden bank nationalizations in 1982 that shocked sectors of business.

The capitalist class did gain more direct domination of the government in fusion with the elites of the two old parties, the PRI and the PAN, but failed to establish a legitimated system of contained electoral competition. The neoliberal assault on the national patrimony and the socio-economic rights of the population created great discontent that expressed itself not only in direct actions but also in electoral support for resurgent “revolutionary nationalism” (a Mexican expression of left populism). The promise that competitive elections and a new economic direction would usher in a new day of better jobs, respect for human rights, and decrease of corruption, was belied by the consequences and practices of the new regime of neoliberal accumulation, continental integration, and competitive but shared government (co-gobierno) between the two old parties. The discontent generated by the consequences of neoliberalism threatened to spill over the boundaries of the acceptable neoliberal electoral competition.1

Local resistance to neoliberalism could be repressed or contained but electoral challenges at the national level were threatening to this new system of bounded multi-party competition. The unpopular consequences of neoliberalism led to the powerful resurfacing of “revolutionary nationalism,” the previously official and still strong popular tradition deriving from the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920). When sectors of the ruling party split in 1987-1988 and competed electorally against the ruling party, it gave an electoral channel to this widespread discontent.

The discontent generated by the consequences of neoliberalism threatened to spill over the boundaries of the acceptable neoliberal electoral competition. The government had to rely on fraud to win the Presidency in 1988 for Carlos Salinas (PRI—Institutional Revolutionary Party) and in 2006 for Felipe Calderón (PAN—Party of National Action) And under both the recent PRI presidencies (1988- 1994, 1994- 2000, 2012-2018) and the PAN presidencies (2000-2006; 2006-2012), state violence and human rights violations have grown dramatically, policing has been militarized, corruption continued on a giant scale, and popular discontent was increasingly quelled by force. These conditions, along with the fierce bitterness of disputes within and between the major parties, have discredited them enormously and have led to the massive lead in polls by Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

In 2000, the hope that the end of one-party rule would open the door to democratic reform and social justice led many people to cast a strategic vote for the right-wing PAN and Vicente Fox for President. This brought one-party rule at the national level to an end. But the PAN, the party of big business and the church hierarchy, continued to push full-speed ahead on the neoliberal assault in alliance with the PRI, the old ruling party and later with the support of the PRD (Party of the Democratic Revolution), which had started as a genuinely oppositional and anti-neoliberal party when it formed in 1988. The victories of the precursor to the PRD in the presidential elections of 1988 and the PRD in 2006 were denied through fraud, fraud legitimated by the efforts of the PRIAN (PRI-PAN alliance) in order to keep Mexico firmly on the path of neoliberalism. Over time, the PRD leadership, some of it coming from schisms within the PRI, fell into the temptations of corruption and electoral opportunism and were coopted by the PRIAN. All three parties signed the Pacto por México (Pact for Mexico) with President Enrique Peña Nieto (PRI), in support of the consolidation of the neoliberal transformation of Mexico on December 2, 2012, one day after his inauguration.

AMLO and the Politics of Morena

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the PRD candidate for President in 2006 and 2012, broke with the PRD and formed a new movement, Morena, the National Regeneration Movement, which later became a political party. It has recruited local, regional and national candidates of many persuasions and past party affiliations. He is a candidate of a coalition, including a small left party and a small right-wing evangelical party. Morena has encouraged many adhesions from different parties so that many of its candidates at local, state, and national level do not come from or share the politics of Morena – which itself already had an inner diversity but a narrower inner diversity. It’s not only the proposed cabinet that is multi-class, multi-party and politically diverse but candidates at all levels. Though an AMLO victory might not immediately give Morena a Congressional majority, it is very likely that there will be enough defections from the other parties to eventually form a majority, given the movement of bloc of delegates between parties that often occurs in Mexico. But, as with the proposed cabinet, it will be a de facto multi-party majority, not held together by any ideological glue or political consensus but by political or instrumental loyalty to the President. All three old major parties are in crisis with bitter internal disputes, splits, and significant migration of leaders and base to Morena, especially as its victory has come to seem more and more likely. This has made the victory of Morena even more likely and the meaning of that victory even more ambiguous.

The discontent that has fuelled the rise in popularity of AMLO has roots in the multiple crises of Mexico. But the crisis that has received little discussion from any of the candidates as well as by the supporters and opponents of AMLO is the fiscal crisis of the Mexican state. It is the elephant in the room. Its consequences have been crucial in generating support for Obrador and its harsh reality will exacerbate the contradictions in his rhetoric and program of “primero los pobres” (the poor first), rhetoric and proposals not accompanied with a proposal to raise taxes or challenge the power of capital. Should he win, he will soon face the reality of these contradictions even if capital does not deliberately seek to sabotage his regime, which it very well may. He will face tough choices that will challenge his ability to hold together his left-center-right multi-class coalition. His promise of “republican austerity,” i.e., cutting excessive salaries, benefits and corruption at the top to pay for redistributive programs for the poor, even should it be carried out effectively, will not get rid of the elephant in the room.

Mexico’s financial balance sheets have deteriorated sharply since the start of the global financial crisis of 2008 leading to a deep fiscal crisis of the Mexican state. The crisis has four major sources. Oil revenues of the state company fell from 8.9% of GDP in 2012 to only 3.8% in 2018. Secondly, there was a massive increase in public debt used by successive governments to offset deficits in order to maintain economic growth in an adverse global environment. Between 2008 and 2018, the weight of the debt in relation to GDP doubled as the accumulated public debt grew from 21% of GDP in 2008 to 45.4% of GDP in 2018. With the increase of the interest rates in the international debt markets, the debt service will absorb 600 billion pesos in 2018, 20% more than that allotted for health, education and poverty reduction in the federal budget. In just one year, from 2017 to 2018, the cost of servicing the debt increased by 24%. The third source of the crisis is the lack of funds for the pension liabilities of the federal government, which would require 2% of GDP to comply with the obligations contracted by the Mexican government in previous years. Finally, the revenue gains made by the fiscal reforms in the first three years of the Peña Nieto presidency, which raised tax revenues from 8.3 to 13.5% of GDP, have since failed to increase government revenues further.

This fiscal crisis, along with the privatization policies of neoliberalism, has had harsh consequences for most Mexicans. The availability and quality of already very poor public services have declined sharply along with the decline of revenues. It has fuelled the rise of support for Obrador as his attack on corruption has resonated with large sectors of the population that already believed that corrupt politicians and public officials are the cause of such great poverty and poor public services in a country with so much natural wealth. Corruption on small and massive scales is an endemic problem and serious drain on public resources. But it is only part of the problem and an attack on it, by itself, will not solve the fiscal crisis nor the various problems flowing from the weakening of the national government by neoliberal policies of the devolution of powers to lower levels of government and the creation of fiefdoms controlled by warlords (drug gangs in alliance with different levels of the state).

AMLO, who comes out of the more nationalist and populist wing of the PRI has never been anti-capitalist but anti-neoliberal. His rhetoric is a populist not a class or anti-capitalist rhetoric. He talks of the struggle of the people against a small elite that he calls the “mafia of power” (corrupt politicians and the super-rich), rhetoric that led to a war of words with the super-rich that ended, if not in peace, in a truce after he met with the Consejo Mexicano de Negocios (CMN – Mexican Business Council), the peak of the peak of Mexican capitalist power. The CMN, a group of around 60 of Mexico’s super-rich, is a smaller and even more elite group than the Business Roundtable in the U.S. or the Business Council of Canada with whom they often work in favor of NAFTA and neoliberalism.

In hopes of winning the election, he has softened his critique of neoliberalism both rhetorically and practically. He has named representatives of big business to the key economic portfolios in his proposed cabinet. He has persistently attempted to reassure business and the U.S. that he is not anti-business, that property rights will be respected and that there will be no nationalizations. He says he will propose an “Alliance for Progress” for Mexico, Canada, the U.S., and Central America, strategically choosing the language of John F. Kennedy’s counter-insurgency plan to stop insurgencies stimulated by the Cuban example.

Even so, his obvious sympathy for the plight of the poor and oppressed, his slogan of primero los pobres, his tough rhetoric on the mafia of power, his promise of democratic labour reform, and his commitment to reverse the neoliberal educational reforms, have led both Mexican and foreign big business to continue to distrust him. They appear to have accepted that their attempts to vilify and defeat him appear to have failed this time. The private media giants, such as Television Azteca and Televisa, which either ignored or completely vilified him in 2006 and 2012, gave a great amount of coverage to his massive closing campaign rally while giving little coverage to the much smaller rallies of his two main opponents.

Should he win, these divergent and contradictory commitments will need to be carried out in the context of the deep fiscal crisis of the state and of the continuing set of crises mentioned above, crises that may accelerate with the fear of big business, corrupt politicians, military and police officials, fear that AMLO will move against their power and privileges after his victory. His promises to root out corruption are threatening both to government officials and capitalists deeply embedded in practices of crony capitalism and kleptocracy. His promises and rhetoric of favoring the poor leave business very uneasy even as he seeks to reassure them with soothing rhetoric and pro-business cabinet appointments. Business understands – and hopefully they are right – that he may be letting the genie of hope and rising expectations out of the bag. Thus, while some sectors of capital see him as a hope for a new stability, larger and more powerful sectors continue to see him as a dangerous prophet.

A Political Opening of Uncertainties, Contradictions and Struggle

The Obrador movement is many things at once. It is a home to many leftists and grass roots activists. And it is a new home for politicos of all three decaying parties to continue their careers and influence. It is a threat to established interests which will seek to contain, channel or defeat it. But it is also an expression of an insurgency from below, an insurgency that has been, for the moment, channelled into the electoral path but continues to also live outside electoralism. The insurgency is real, powerful, rooted in the rebellious traditions of Mexican popular culture, and the deeply oppressive conditions suffered by most of the Mexican population.

A victory of AMLO would open a new moment in Mexican history but the character of that moment is not clear. It will be determined in a complex process involving the Obrador presidency, big business, and grass roots movements of workers, peasants, and students. AMLO, in the Bonapartist tradition of Mexican revolutionary nationalism, will seek to manage the class conflicts in the “national interest.” The maintenance of such a cross-class equilibrium will, of course, be extremely difficult given the very limited means of maneuver of the state because of the fiscal crisis and the presence of another elephant, always present in the room of Mexican sovereignty, the United States. The U.S. state and capital will play a major role in trying to contain popular movements and any leftward direction of the Mexican government. And the current erratic and racist U.S. President may continue to make interventions that both heighten instability and have unpredictable consequences in the Mexican situation.

An AMLO government would open up significant possibilities for the growth of unions and popular struggles by ending the extreme repressiveness of the national government, something that would not happen should either of the other two major candidates win. At the same time, his strategy of reassuring capital will lead to not just tough but impossible dilemmas for him. He is likely to try to manage the explosive contradictions within his alliance by attempting to keep a lid on demands from below, demands that surely will grow with the hopes encouraged by his victory.

While business always has great levers of power in a capitalist society to pressure and channel governments and to make the rest of the population pay for their profits and misdeeds, workers, peasants and the poor only have power if they are organized collectively and have strategies of solidarity and transformation. It is essential to build independent workers’ and popular movements and as well as a Left independent of AMLO if these divergencies and contradictions are not to be resolved on the backs of workers, peasants, and the poor. The attainment of that self-organization would have to be achieved despite the power of capital to divide and despite the plebiscitarian tendencies of AMLO himself. Workers, peasants, the poor, and the Left need to seize the possibilities that an AMLO victory would create. But they need to do so without illusions of beneficence from above and with readiness to fight independently alongside the new government or against it, depending on the issues and the circumstances. •

Endnotes

- The National Indigenous Congress (CNI) and the Zapatistas proposed to run María de Jesús Patricio, an indigenous woman who goes by the name “Marichuy,” as a candidate for President. They had no expectations of winning the election but saw the campaign as an agitational and educational initiative. This strategy was both similar to and different from “The Other Campaign” of 2006. The “Other Campaign” pointedly stayed out of the formal electoral process. The 2018 initiative sought to run a similar educational campaign but from within the electoral process. The effort was cut short by their failure to get enough signatures nation-wide to qualify. The CNI, the Zapatistas, and most of the indigenous movements have been wary of AMLO and continue to maintain their organizational and political independence.