The Stanley Cup Finals: Festival of Exploitation?

The Stanley Cup Finals have arrived. For ardent hockey fans and their proxies in the mainstream sports media, this is the triumphant culmination of an epic journey of athletic mastery and heroic stoicism. It is the season to wax poetic about the “grit,” “toughness,” “pain,” “heroism,” and “sacrifice” that define professional hockey players and render them worthy of a sip from the silver chalice.

Or some such nonsense. Yes, this is a narrative that sells tickets and buys clicks, but don’t be fooled: it is also one that deftly conceals the violence, harm, and exploitation that underpin the business of professional hockey, much like most other high-performance spectator sport.

Or some such nonsense. Yes, this is a narrative that sells tickets and buys clicks, but don’t be fooled: it is also one that deftly conceals the violence, harm, and exploitation that underpin the business of professional hockey, much like most other high-performance spectator sport.

Now, I recognize that for many, the claim that professional hockey players are exploited will come across as uncomfortable, if not intolerable. Athletes are beyond white collar – they are one-percenters wallowing in wealth and privilege. Aren’t they?

Unsafe Working Conditions

The truth is that the conditions of athletic labour share more in common with the version of industrial capitalism Marx confronted in the mid-19th century than they do with Wall Street or Silicon Valley. While most elite pro athletes are compensated in a manner completely incommensurate with the factory workers of Marx’s day (although, try telling that to minor league baseball players or NCAA athletes), there is a dimension of their work that is disconcertingly analogous: the fundamentally unsafe working conditions.

In Chapter Fifteen of Capital, Marx describes the factory system as the “systematic robbery of what is necessary for the life of the workman while he is at work, robbery of space, light, air, and of protection to his person against the dangerous and unwholesome accompaniments of the productive process.” A salient feature of proletarian existence as Marx understood it was insecurity of person on the job. While workplace safety laws such as the 1970 U.S. Federal Occupational Health and Safety Act – which states that an employer “shall furnish to each of his [sic] employees employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his [sic] employees” – at least nominally protect most U.S. workers today, athletes are apparently an exception.

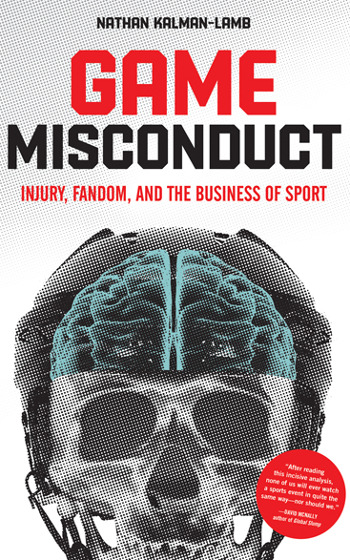

Elite hockey players, including, no doubt, those currently labouring for the Las Vegas Golden Knights and Washington Capitals know this reality only too well. In interviews for my new book Game Misconduct: Injury, Fandom, and the Business of Sport, former professionals described their experiences with injury in the course of their work. One long-time high-profile player told me:

“One year, I got my jaw broken. A guy hit as I was trying to stay in the line-up, playing with a guard on my helmet that would allow me to play even if I had a broken jaw. I got hit a few more times during the year and ended up re-breaking it twice. When you play with a broken jaw and your helmet has this big thing around your face to protect you, everybody knows that you are playing hurt. Believe it or not, those three times that I got my jaw broken, the only thing that happened was one two-minute penalty [laughs]. The other times that I got hit, players did not even get penalized. So that’s part of the frustrations that come with that. And the dirty hits and the dirty slashings, and all that stuff, there’s nine of my ten fingers that have been broken. And I have never missed a game because of broken fingers. So again, it’s just an example of what players go through. You play with broken ribs where you have a tough time breathing and stuff like that. There’s all kind of things that you go through and you battle through and that people don’t really know about.”

Another player, a former enforcer, explained:

“I suffered a broken orbital bone where they had to put a plate underneath the eye. A broken tibia and fibula in my ankle, which put me out all year. And then a tendon on my left thumb that was off the bone and they had to put it back on. I had no idea [about concussions]. It was more of a, you didn’t feel well or you were sick. But you went out and played again, right away. So, there was no protocol for getting knocked out back then… I think I had one that was diagnosed, maybe two. But I had a hundred and some pro fights, right? So … I was told [I probably suffered] around seventy-five grade one concussions.”

As players struggle to play through the pain in order to satisfy their employers and fans, they accumulate an inordinate amount of damage to their bodies. A major study in the British Journal of Sports Medicine tracked every player in the NHL over a six-year period and found that on average, each experienced at least one injury a season that required them to miss playing time – not including injuries they ignored in order to keep playing. Moreover, according to another study, the part of the body most frequently injured in contact sports is none other than the head. This is particularly significant given that repeated head injury (or concussion) leads to Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, symptoms of which include depression, aggression, and even suicidal ideation. Little wonder, then, that while professional hockey may provide short-term incentives to make physical sacrifices (income and prestige, for instance), players’ perspectives shift once careers end and the reality of the harm to their long-term health sets in.

A former American Hockey League (minor professional league to the NHL) goaltender told me, “When you’re 24 years old, injuries don’t mean anything to you. You just want to play hockey. Now that I’m 39, I realize, wow, maybe I should have [taken] some more time off, because of my future, and, you know, doing stuff around the house or with my kids.”

The former enforcer quoted above gives an even bleaker portrait of post-career life: “Memory loss, tension headaches, that kind of stuff, I mean it’s [long pause] … I don’t know how to put a finger on it, but … I don’t like to rehash any head problems that I had or any injuries. I’m trying to move on with my life.” Indeed, another former player declined to speak with me at all, despite the exhortations of his partner, because the trauma of the harm he experienced from concussions in pro hockey was too fresh.

Career Cut Short

Another former player, whose career was tragically cut short due to a knee injury that was grievously mis-handled by his team’s medical staff, is less circumspect about the toll of injury on his life:

“I’ll need a knee replacement because the last surgery or last checkup I had, my knee is very arthritic because of the rubbing, bone on bone. The shoulders will pop out every once in a while, and I have to do some exercises to get them back in. My back aches regularly. The first thing I do in the morning is I take pain medication and I’ll follow it up with probably pain medication later on in the day, depending on how I’m feeling, but everything hurts [laughs]. When the weather changes, I’m like the old man on the rocking chair, I can tell when the weather is gonna turn bad just because the way my joints are feeling. I can’t run, so I’m limited physically in what I can do, so there’s no quick sports like basketball or tennis or any of those kind of things. Biking is fine, swimming is fine, I still skate occasionally, but I can’t perform, obviously, like I was, or like a younger man would. But to me, the biggest issue that I deal with is pain … [The concussions] affected my memory. I need to write everything down, otherwise I will forget most tasks and if somebody tells me something or they want me to do something, I tell them either send me an e-mail or I have to write it down, otherwise I’ll forget certain things. You know, I’m very good with numbers, I can remember numbers, I can remember phone numbers and locker combinations and all that sort of stuff, but details or conversations that I have with people or names and so on, I think it has affected my memory on those things.”

Analysis of labour in professional sports like hockey seductively invites a liberal take. After all, don’t players transparently provide their consent to put their bodies at risk in return for wealth and status that few of us can imagine? The answer to this question is no different than for other forms of labour under capitalist conditions, which is to say that the decision to exchange labour for a wage is always one made under duress. Players don’t get a meaningful say in the nature of their working conditions; they must accept them as they are or cede the ambition to become a professional hockey player. Given that our culture tells its youth that professional sport is among the most edifying forms of human experience attainable, that’s an awfully big ask.

“Players don’t get a meaningful say in the nature of their working conditions.”

So, even as the Las Vegas Golden Knights and Washington Capitals are exulted in the coming days for having reached the pinnacle of their profession, remember that each additional game they play – every puck they dive to block and crushing body check they struggle to absorb – is another moment in which they are being subjected to the dangerous and unwholesome accompaniments of the productive process and thus robbed of what is necessary for the life of the worker while at work. Namely, the promise of a healthy future in which to reflect on those accolades. •