French Railworkers on Strike

The philosopher Étienne Balibar is one of the figures behind the solidarity fund in support of striking railworkers in France – a fund that now stands close to €1-million. Responding to questions from workers who are taking part in the rolling strike action, Balibar emphasized the need for what he calls “collective resistance against social regression.”

Anasse, a pointsman at Le Bourget: How can an intellectual today show solidarity with workers’ strike action?

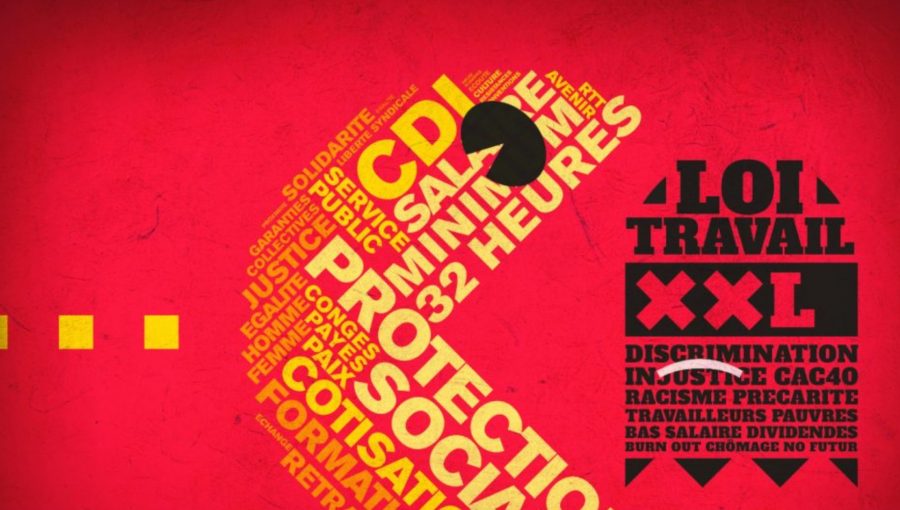

There are (at least) two reasons for them to do so, and indeed these reasons overlap. The first reason is that the railworkers who are today defending fundamental social rights are also fighting to stop the rail service itself being dismantled. This is not just any company. It is an essential public service, and now we see various attempts to privatize it (opening it up to competition and aligning its rules of functioning with the managerial norms of private businesses). This is part of a general offensive, which we might call a “neoliberal” offensive. After the attacks on the post office and telecommunications, they are trying to get rid of an essential public service. And other important sectors are also in the firing line.

The second reason is connected to this. As a teacher and researcher (I entered the education system as a trainee teacher in 1960, and today I am an “emeritus” professor) I spent my life working to serve citizens, and not so that a company could make profits. The railways and education are not the same thing, but they do together make up part of a wider whole. And now competition-based standards of evaluation and management are also penetrating into the education system. So I welcome the railworkers’ strike, for the strikers are in the vanguard of the collective resistance to this social regression.

Karim, Landy maintenance centre: It is said that our status is a privilege dating back to a time that has now passed. In your view, what, today, is a right and what is a privilege?

That’s an essential question! The terminology around “privilege” is a propaganda tool, which is used to discredit the railworkers’ resistance against their status being dismantled (or condemned to future extinction). Their status is presented not only as somehow archaic, but as if it were indirectly exploiting other workers. This is the height of nonsense, when we actually look at the railworkers’ wages and working conditions. Without doubt, there are privileged people in our society, in which we can see an exponential rise in inequalities of wealth and power, inequalities before the tax system, and inequalities in terms of who gets to have their say. But these privileged types are not working on the railways. We would be better off looking for them in the Stock Exchange or in Neuilly [posh neighbourhood on the western edge of Paris].

Besides, the very idea of democracy (from the French Revolution onward) has always been based on the elimination of privileges – which have a class character – and the recognition of rights – which are, on principle, universal. Rights belong to everyone. In the nineteenth and particularly the twentieth century, these rights also began to include social rights, social security, and protections for workers. This was not the result of the ruling classes’ goodwill, but long and arduous struggles, and exceptional – sometimes even dramatic – circumstances. We should remember that the railworkers’ current status was established in two phases, in the aftermaths of the First and then the Second World War. That is no coincidence! In resisting the dismantling of their status, today’s railworkers are defending this historical inheritance and its continuation for the future generations, who risk living in a society of generalized precarity.

Laura, a pointswoman in Le Bourget: The strike could get tougher over time. They are talking about us as if we were taking people hostage. What do you think about this?

First of all, I should say that my hope is not that the strike “goes on” indefinitely, but that it wins, especially considering the general interest that it embodies. But given the positions to which the government is currently holding firm, it is possible that the strike will indeed have to get tougher, and endure for longer, if it is to emerge victorious. It will be essentially important, therefore, to win the battle of public opinion, to secure the understanding and if possible the active support of the service users (the large majority of whom are also workers). Given the inconvenience that a transport strike will cause for everyone, it is hardly self-evident that the strike will indeed win over public opinion.

“Intellectuals” like us have to do as much as possible to help make this happen. That is, insofar as intellectuals are able to make ourselves heard and affect public opinion (a French tradition that also needs protecting). Just like when they speak of “privileged” workers, the reference to the strikers “taking people hostage” is also mere propaganda. It is so over-the-top that I would be astonished if it worked. But we never know how public opinion could turn, and the government will stop at nothing to make the strikers look like “hardliners,” “selfish,” “terrorists,” etc. So, a lot will depend on the force of the movement, which will need to be united, to keep its cool, to be democratic, and to be clear in its objectives. Here, too, we intellectuals can play a role, even without ever substituting for the railworkers in struggle. •

This article published on versobooks.com website.