At the Interstices of Race, Class and Imperialism: A. Sivanandan (1923-2018)

Ambalavaner Sivanandan, who has died aged 94 in London on 3 January 2018, was an organic intellectual working at the interstices of race, class and imperialism. A skillful essayist and gripping orator, he chiselled powerful idioms and imagery which travelled across his writing, and from his speeches to his writing, and back again. His prose was crafted not so much to be read quietly, as recited aloud.

What animated him, in contrast to liberal-left academics and media commentators of colour fixated by issues of representation and privilege, was the question: “… what is it in the black and Third World experience, in the experience of the oppressed and exploited, that gives one the imagination to see other oppressions and the will to fight for a better society for all, a more equal, just, free society, a socialist society?”1

Sivanandan – probably in the spirit of an exasperated Karl Marx who against some of his followers once protested “[if they are Marxists], then I am not” – spurned that identification. He believed Marxism to be hidebound by its European origin and ossified by its adherents into a secular dogma or faith: more hindrance than help, in seeing and acting upon, a constantly revolutionising capitalism. Still he recorded his debt to Marx, through whom he found “… a way of analysing my own society, a way of resolving my own social contradictions, a way of understanding how conflict itself was the motor of one’s personal life as well as the combusting force of the society in which one lived.”2

Initially he appeared attentive to the radicalism of the women’s liberation movement, noting in 1973 its potential for the clarification of issues of working class and black struggle in “The Colony of the Colonised: Notes on Race, Class and Sex.”3 However, he was distanced from feminism, thinking it to be captured by middle-class women for the extension of their own rights, rather than for social change for those women and men whose freedoms are most trammelled.

Asian and Afro-Caribbean Struggles

Perhaps his most widely-read work is From resistance to rebellion: Asian and Afro-Caribbean struggles in Britain,4 where he chronicled the self-activity and self-organisation of immigrants from the ex-colonies, against injustice and for dignity and equality, reconstructing their history. Despite references to black women’s organising, he was less successful in integrating their specific experiences in his narratives.

His investigations of the political-economy of racism – the racism that kills, more than the racism that discriminates – informed a generation of social workers, school-teachers, university students and lecturers, and campaigners for self-defence of black communities. Subsequently, he made connections between the new scapegoats of state, popular and ‘Fortress Europe’ racism – refugees and asylum-seekers, working-class Eastern Europeans and Muslims – and imperialism; as he had between their predecessors and colonialism. “[I]t is your economics that creates our politics that make us refugees in your economies,” he retorted to the votaries of immigration control and purveyors of xenophobia5 or ‘xeno-racism’ in his coinage.

His early writing on “Black Power: The Politics of Existence” (Politics and Society, 1971) and “The Liberation of the Black Intellectual” (Race & Class, 1974)6 – the former, sympathetically interrogating an insurrectionary movement in the United States; and the latter, challenging its intellectuals to find through their consciousness of colour, the consciousness of class – was retrieved from the archives by African-American scholars in the 1990s. They were seeking to illuminate the limitations of a cultural nationalism of the oppressed (‘Afro-centrism’) indifferent to capitalism, in its production of oppression, and to the reproduction of relations of exploitation and inequality, principally gender and class, among the oppressed.

At the onset of what would become known as ‘globalisation’, Sivanandan intervened in debates on the latest stage in the development of capitalism. In “Imperialism and Disorganic Development in the Silicon Age,”7 he identified three features: a new international division of labour and production where capital (from rich industrialised countries) moved to labour (in poor industrialising ones); the movement of labour (internal and transnational migration) within the periphery (to export processing zones at home and petrocarbon producers abroad); and a new industrial revolution based on micro-electronics. However, where its promoters predicted that parts (at least) of the Third World were on track to the terminus of western capitalism and liberal government; he saw them shunted to ‘disorganic development’: capitalism sans capitalist culture or capitalist democracy.

A decade later, globalisation’s progress was tracked in “New Circuits of Imperialism.”8 In the advanced capitalist world, deindustrialisation and automation had ravaged working class communities and enervated trade unions. Capital, he controversially pronounced, had freed itself of labour. In the dependent capitalist world where manufacturing had relocated, and where some Latin American and Southeast Asian countries were newly-industrialising, economic growth had not removed the mass of people from poverty, hunger and hopelessness. Humanity possessed the technological means to increase productivity with less labour, to distribute work more equitably, to increase time for creative leisure, and to provide a basic income to all. However, this won’t and can’t happen under capitalism, he insisted.

Already Sivanandan was taking issue with others, including his Jamaican-born friend and cultural theorist Stuart Hall, who shared his view that capitalism was in the throes of an epochal shift, but who drew political conclusions diametrically opposed to his. In “All that melts into air is solid: the hokum of New Times,”9 he pilloried erstwhile Communists and their fellow-travellers, who – in their disappointment in the labour movement; befuddlement at the rise of Thatcherism (that is, neoliberalism with British characteristics); and in the zeitgeist of postmodernism – had taken flight from class politics.

Many Marxists made common cause with his intransigent defence of the socialist project; but resisted as did Ellen Meiksins Wood,10 the assumption that globalisation is the inevitable or natural consequence of technological change rather than a political, and therefore reversible, strategy of capital.

British Ceylon

Born on 20 December 1923 in British Ceylon’s capital on the verdant multi-ethnic, multi-lingual and multi-religious south-west littoral, his father – who had escaped the privations of peasant farming, through the route of English education, to join the colonial government service as a postal clerk – was from the Tamil Hindu village of Sandilipay in the parched northern peninsula of Jaffna. From Sivanandan’s own induction into the premier Catholic boys school of St. Joseph’s in Colombo, he was to acquire two abiding traits: his adoration of English poetry and his disavowal of religious belief.

Though aligned with the Left from his youth – formative influences at the University of Ceylon, where he read economics and political science, were the academics and visiting leaders of the Trotskyist Lanka Sama Samaja Party – ahead of him may well have been the unexceptional petit-bourgeois life of the banker he became or barrister he aspired to be; except he was a disputatious Tamil in post-colonial Ceylon (renamed Sri Lanka in 1972) where Sinhala Buddhist nationalism was waxing.

The anti-Tamil riots of May 1958 brought the first part of his life to a close. Disgusted by the savagery in which he was caught up, amid the collusion of the state and its discriminatory treatment of the Tamil minority, Sivanandan – to be followed by his Sinhala Catholic wife (their inter-ethnic and inter-religious marriage was opposed by their families) and their three children – emigrated to England, initially living in West London.

As he vividly recalled, he had walked out of one riot, only to walk into another. In late August and early September of 1958, the Notting Hill riots broke out, where racial clashes were preceded by fascist assaults on men of Caribbean-origin, to the disinterest of local police.

Black in Britain

Unprepared for, and battered by, the racism swirling around him, he said: “I knew then I was black.”11 To be black, he explained, was not to do with the colour of one’s skin, but the colour of one’s politics or the colour of one’s fight. It was an affirmation of the consciousness of racism and colonialism that bound immigrants from across the British empire and forged them into a new working class in a declining imperialism. And in its articulation, it owed not a little to the black power movement on the other side of the Atlantic, and to revolutionary nationalism in the colonised world. While he never gave up on affirming his blackness, the communities of the oppressed unglued themselves, before fragmenting into ever-more sectarian and inward-looking identities.

There was no going back to the middle-class status and life he had experienced in Sri Lanka. The colour bar operated in Britain not to deny work to black people but “instead to deskill them, to keep their wages down and to segregate them in the dirty, ill-paid jobs that white workers did not want.”12 In his mid-thirties, the ex-banker was now serving tea at Kingsbury public library. He turned adversity into opportunity by using his location to read, think and self-educate. He enrolled for evening classes to study librarianship; eventually becoming one in his place of work. None of this came easy, nor without cost. His marriage frayed and finally wore out; and he was now the sole carer for Tamara, Natasha and Rohan.

Institute of Race Relations

By 1964, he joined the Institute of Race Relations (IRR) as librarian (via the Colonial Office!), and was politically active in the mobilisations, self-help groups and self-organising of black people including the Black Unity and Freedom Party. His public writing begins from this time, peaking between the 1970s and 1990s. An outpost of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, the IRR was funded by multinationals and run by white pro-establishment figures. It studied race and its management as an academic field and did nothing to combat racism.

Sivanandan and some others chafed at its unwillingness to engage with what “black people were undergoing [in Britain] in terms of racism and in the Third World in terms of colonialism and imperialism.”13 In 1972, they took control of its board, with Sivanandan at the helm as the IRR’s new director, but bereft of other resources but the library, two other staff including Jenny Bourne whom he later married, and loyal volunteers.

Deploying their networks and allies, they began turning the IRR into a “think-in-order-to-do-tank, for black and Third World peoples.”14 At the core of its philosophy was that “the function of knowledge is to liberate…to apprehend reality in order to change it.”15 Its mission he constantly reminded himself and others is “… to ensure that that the people we are writing for are the people we are fighting for.”16

Race & Class

Connecting racism with imperialism, and imperialism with capitalism, and capitalism with racism – mindful of the relationship between oppression and exploitation, within black communities, and in the former colonies – the IRR’s flagship publication was renamed Race & Class, proclaiming its purpose in its masthead as “A Journal for Black and Third World Liberation.”

As its founder-editor, Sivanandan published Eqbal Ahmad, John Berger, Malcolm Caldwell, Angela Davis, Basil Davidson, Orlando Letelier, Cedric Robinson, Walter Rodney and Edward Said among others; and later Aijaz Ahmad, Jenny Bourne, Victoria Brittain, Liz Fekete, Barbara Harlow and Manning Marable, in its pages.

Among highlights for readers were his piercing book reviews and pungent obituaries of heroes and villains: African-American auto-worker and revolutionary organiser James Boggs among the former and Enoch Powell, the Urdu-speaking English and Unionist politician and racist tribune, of course the latter.

However, he is best known for excoriating but always stylish essays in Race & Class, exhibiting his sharp intellect, unflinching commitment and lyrical prose. He was, in his own words, a pamphleteer: “writing for that time, for the struggle, not for all of time.”17 His long-form work focussed on the politics of black liberation in Britain and the USA; imperialism and capitalism in the core and the periphery; and the mutations of racism in Britain and Europe.

These are collected in A Different Hunger: Writings on Black Resistance (Pluto, London 1982) and Communities of Resistance: Writings on Black Struggles for Socialism (Verso, London 1990). Selections from both books, as well as newer writing, have been published as Catching History On the Wing: Race, Culture and Globalisation (Pluto, London 2008). The subtitles of these three volumes are revealing in themselves as a sign of the changing times which shaped their content.

When Memory Dies

In his country of birth, Sivanandan is recognised, if at all, by his fiction. When Memory Dies (Arcadia, London 1997) was published when he was 73 years of age. It was followed three years later by a collection of short stories (some previously published in literary magazines in Sri Lanka) gathered together as Where The Dance Is (Arcadia, London 2000). A second novel was underway in his late eighties but held up by annoyances of age and health.

An epic work of historical literature sweeping across 20th century Sri Lanka, the novel was composed he said, because “… there was a hollow in me, where my country was, and I had to fill it with its story.”18 Its detail draws on Sivanandan’s youthful recollections of Colombo and Jaffna, and of the Kandyan highlands where he briefly taught in rural schools. Awarded a Commonwealth Writers Prize and the Sagittarius Prize, both in 1998, it was written over two decades. It has taken another two for a Sinhala-language translation to get underway, with none in sight in the Tamil language.

Interwoven in the tale of three generations of one family, is Sri Lanka’s passage from the era of late colonialism with its plantation and mercantile capitalism through to the dependent capitalism of the post-colony. The book opens with the rise of the labour and left movement, tracks the unfulfilled promise of decolonisation; the wavering before, followed by capitulation to, ethnic chauvinism by the Left parties; the corrosion of inter-ethnic relations across classes, through casual and institutionalised racism and punctuated by pogroms; and the rise of Tamil armed opposition to ‘state fascism’, before closing with the self-destructive consequences of that militarism and the dream of liberation deferred.

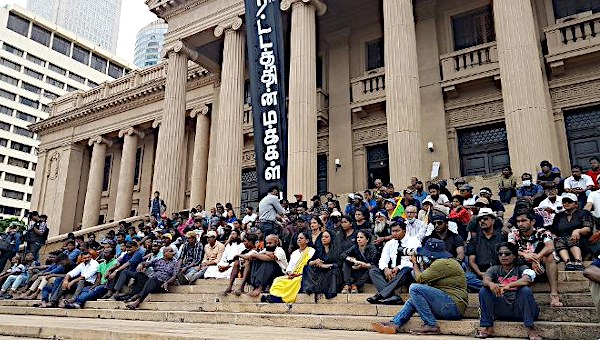

Sri Lanka

Astonishingly, Sivanandan’s non-fiction, though sporadically extracted in Tribune, Economic Review and Lanka Guardian, is undiscovered in Sri Lanka. This includes “Sri Lanka: racism and the politics of underdevelopment”19: composed in the embers of the murder, arson and displacement of Tamils during the July 1983 riots; and as new fires were lit in a protracted internal war between the state and myriad Tamil militant groups: each succored by its respective nationality. A primer on the surfacing of Sinhala Buddhist nationalism through the alliance of colonialism and underdevelopment and its maturation under market state authoritarianism, this commanding survey draws on the work of the historian Kumari Jayawardena and sociologist Newton Gunasinghe, while typically deepening and extending their insights.

Twenty-five years later, in a wide-ranging synopsis of the history and dynamics of the ethnic conflict, culminating in a devastating end to a devastating war, Sivanandan despairingly pronounced that “fifty years of ethnic cleansing have … made cohabitation with the Sinhalese people virtually impossible.”20 He was reacting to the permissiveness, as he saw it, of international actors in the enormous loss of Tamil lives in the military endgame; the cruelty of the mass post-war internment of Tamil civilians, recently under the control of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE); and the frightful political and human rights environment for Tamils, Sinhalese and Muslims alike, under accelerating militarisation, during the Rajapakse regime.

In 1984, when Tamil militant organisations still claimed some attachment to socialism, before the fratricidal killings within their movement, and when their repressive character was still not evident, Sivanandan idealised them in the tradition of the liberation movements in Portuguese Africa. They were “freedom-fighters” and the last line of defence for Tamils and Sinhalas alike, against the “mounting dictatorship” of J. R. Jayewardene’s dharmishta (‘righteous’) rule. Even so he cautioned them: “Tamil liberation is the easier won through the weakening of the Sinhala state from within, socialism the surer achieved through struggles not narrowly nationalist.”21

“Weaponry was in command, not politics. This was a critical weakness, and it created the conditions for the final defeat in 2009.”

Subsequently he was more sober in his assessments, as evident from the conclusion to When Memory Dies. After the LTTE had been crushed in May 2009, he faulted it for its elimination of opponents and critics within Tamil political and civil society; ethnic cleansing of the ethno-religious Muslim minority from Tamil-majority areas; and alienation from the Tamil people. The “… political dimension of their struggle had been subordinated to an ad hoc militarism; the military tail had begun to wag the political dog … Weaponry was in command, not politics. This was a critical weakness, and it created the conditions for the final defeat in 2009,” he contended.22

Human Condition

Sivanandan once observed how “racism particularizes us, class and gender exploitation particularizes us – but in fighting those things we should not ourselves become particular and self-seeking … To fight racism is not to become racist ourselves, to fight privilege is not to become privileged ourselves.”23 He was emphatic that “any struggles of the oppressed, be it blacks or women, which are only for themselves and then not for the least of them, the most deprived, the most exploited of them, are inevitably self-serving and narrow and unable to enlarge the human condition.”24 Anyone who aspires, as he did, to understand the world in order to change it, irrespective of origin, location and cause, must inevitably seize this standpoint. •

Endnotes

- A. Sivanandan, “The Heart is Where The Battle Is: An Interview with the Author” (by Quintin Hoare and Malcolm Imrie) in Communities of Resistance: Writings on Black Struggles for Socialism, Verso, 1990, p. 15.

- Sivanandan, “The Heart is Where,” p. 5.

- Sivanandan, A Different Hunger: Writings on Black Resistance, Pluto, 1982, pp. 74-79.

- Sivanandan, “From resistance to rebellion: Asian and Afro-Caribbean struggle in Britain,” Race & Class, Vol. XXIII, nos. 2/3, October 1981, pp. 111-152.

- Sivanandan, “La trahison des clercs” in Catching history on the wing: Race, Culture and Globalisation, Pluto 2008, p. 57.

- Both reprinted in A Different Hunger, pp. 57-66 and pp. 82-98 respectively.

- Race & Class, Vol. XXI, no. 2, Autumn 1979, pp. 111-126.

- Race & Class, Vol. XXX, no. 4, April/June 1989, pp. 1-19.

- Race & Class, Vol. XXX, no. 3, January 1990, pp. 1-30.

- “Capitalism, Globalization and Epochal Shifts: An Exchange,” Monthly Review, February 1997, pp. 21-32.

- Sivanandan, “The Heart is Where,” p. 9.

- Sivanandan, “From resistance to rebellion,” p. 112.

- Sivanandan, “The Heart is Where,” p. 12.

- Ibid.

- Editorial, Race & Class, Vol. XV, no. 4, April 1974, p. 399.

- Sivanandan, “The Heart is Where,” p. 15.

- Kwesi Owusu, “The struggle for a radical Black political culture: an interview with A. Sivanandan,” Race & Class, Vol. 58, no. 1, p. 11.

- Ibid.

- Race & Class, Vol. XXVI, no. 1, Summer 1984, pp. 1-37.

- Sivanandan, “An Island Tragedy: Buddhist Ethnic Cleansing in Sri Lanka,” New Left Review II/60, Nov-Dec 2009, p. 97.

- “Sri Lanka: racism and the politics of underdevelopment,” Race & Class, Vol. XXVI, no. 1, Summer 1984, p. 36.

- Sivanandan, “An Island Tragedy,” New Left Review 60, Nov-Dec 2009, p. 93.

- Louis Kushnick and Paul Grant, “Catching History on the Wing: A. Sivanandan as Activist, Teacher and Revolutionary,” SAGE Race Relations Abstracts, Vol. 25, no. 4, 2000, p. 11.

- Sivanandan, “The Heart is Where,” p 15.