In South Africa, Ramaphosa Rises as Lonmin Expires

Workers, Women and Communities Prepare to Fight, Not Mourn

Monday night’s internal African National Congress (ANC) presidential election of Cyril Ramaphosa – with a razor-thin 51 per cent majority of nearly 4800 delegates – displaced but did not resolve a fight between two bitterly-opposed factions. On the one hand are powerful elements friendly to so-called “White Monopoly Capital,” and on the other are outgoing ANC president Jacob Zuma’s allies led by Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, his ex-wife and former African Union chairperson. The latter faction includes corrupt state “tenderpreneur” syndicates, especially the notorious Gupta brothers, and is hence typically nicknamed “Zupta.” (Zuma is still scheduled to serve as national president until mid-2019.)

South Africa’s currency rose rapidly in value after Ramaphosa won, for he is celebrated by big business and the mainstream media. But he has also gained endorsements – due to quirky local political alignments – from the SA Communist Party, ANC-aligned trade unions and most centrists and liberals who despise the Zuptas. With this base and some nominal prosecutions of corruption, Ramaphosa will likely relegitimize the fast-fading ANC in time for a 2019 electoral victory. However, given the narrowness of his win, he probably cannot engineer Zuma’s early departure as many hoped, in the way Zuma had ousted Thabo Mbeki nine months before his term was due to end in 2009.

Moreover, Ramaphosa’s much-anticipated attempt to clear Zupta muck from the corrupt stables of several parastatal organizations and government departments will fail. Too many ANC patronage systems have become cemented. And three other leaders elected at the congress are high-profile Zuptas with corruption-riddled reputations, including secretary-general Ace Magashule and his deputy Jessie Duarte, as well as ANC deputy president David Mabuza. A new slur, “Ramazupta,” may emerge as the epithet for the coming regime.

Ramaphosa was a heroic mineworker leader during the 1980s, a crafty ANC secretary general under Nelson Mandela during the early 1990s when he led negotiations on many crucial semi-democratic deals with the outgoing apartheid regime, the main drafter of the country’s liberal constitution in 1996, and then – after losing the deputy presidency job to Mbeki in 1994 – a black-empowerment billionaire thanks to joint ventures in mining, banking and ‘food’ franchises McDonalds and CocaCola. He became ANC deputy president in 2012 and in government, became the national deputy to Zuma in 2014.

By the 2000s, Ramaphosa had earned a reputation for seeking profits at any cost. The worst incident was at the Lonmin platinum mines at Marikana, two hours’ drive northwest of Johannesburg. On August 15, 2012 Ramaphosa emailed a request to police – for which he weakly apologized only a few months ago – demanding “concomitant action” against “dastardly criminals,” against whom police should “act in a more pointed way.”

He was referring to 4000 desperately underpaid miners who had been on a wildcat strike the prior week, during which six workers, two security guards and two policemen had died in skirmishes. Neither Lonmin officials nor Ramaphosa wanted to negotiate. The following day, as strikers peacefully departed the strike grounds for their homes in nearby shantytowns, 34 men were shot dead by police, and 78 wounded.

Ramaphosa’s role was especially unconscionable given his struggle history. In the Emmy Award-winning film Miners Shot Down (from minute 13), director Rehad Desai reveals the class-loyalty U-turn. In 1987 in the midst of a legendary strike, Ramaphosa accused the “liberal bourgeoisie” of using “fascistic” methods. Thirty years later Ramaphosa had become the main local investor in Lonmin, and within five years was a “monster,” according to local activists, playing a familiar role described by the workers’ lawyer, Dali Mpofu:

“At the heart of this was the toxic collusion between the SA Police Services and Lonmin at a direct level. At a much broader level it can be called a collusion between the State and capital… in the sordid history of the mining industry in this country. Part of that history included the collaboration of so-called tribal chiefs who were corrupt and were used by those oppressive governments to turn the self-sufficient black African farmers into slave labour workers. Today we have a situation where those chiefs have been replaced by so-called Black Economic Empowerment partners of these mines and carrying on that torch of collusion.”

Lonmin Unlamented

Last week, London and Johannesburg investors witnessed what seems to be the death of Lonmin, a firm born as the London and Rhodesian Mining and Land Company Limited in 1909. Lonrho had languished through the 1950s but then became one of the world’s most degenerate corporations, thanks to managing director Tiny Rowland’s corrupt deals across post-colonial Africa. By 1973 even British Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath labelled Lonrho “the unpleasant and unacceptable face of capitalism.”

One reason for the company’s death was the backlash against the Marikana Massacre. The Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu) became sufficiently strong to wage a five-month strike in 2014. The Massacre also humiliated a high-profile Lonmin booster, the World Bank. Its 2007-12 poster-child treatment of Lonmin’s so-called “Strategic Community Investment“ attracted persistent complaints from a Marikana community group, Sikhala Sonke. These grassroots feminists have rebuffed several bogus “dispute resolution” efforts from Washington, and their stinging legal critique of the Bank was deemed valid by an internal ombudsman earlier this month.

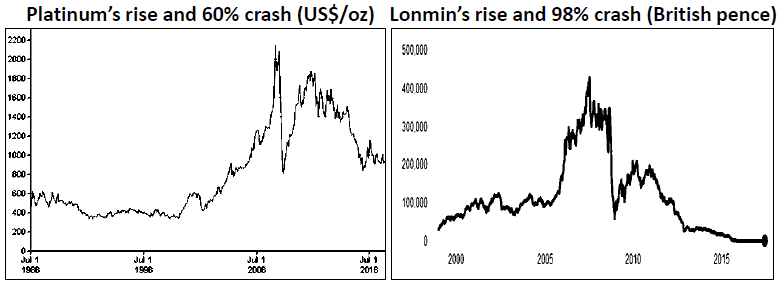

But unless objections by such groups and trade unions prove overwhelming before Lonmin’s annual general meeting in London on January 25, the world’s third largest platinum corporation will be swallowed by the young (five year old) Johannesburg-based mining house Sibanye-Stillwater. The price is a measly $383-million, which is 1/7th Sibanye’s current share value and a tiny fraction (1.4%) of Lonmin’s peak value of $28.6-billion a decade ago.

The company’s complicated postmortem will have two chapters:

- partial suicide – by a wicked management abetted by the Bank and at least one allied politician, Ramaphosa; and

- partial assassination – by the iron laws of capitalist crisis in the form of overproduction tendencies, combined with Volkswagen’s greenhouse gas emissions scam, which together drove the platinum price up too high and in 2015 crashed it too quickly.

Resource Curses Reloaded

Consider the rapid reaction to Sibanye’s takeover by the main union leader representing Lonmin workers, Amcu’s Joseph Mathunjwa: “We are prepared to join forces with communities around Lonmin to ensure that the interests of mineworkers’ mine-affected communities are defended. We want to warn the new owners and current shareholders that we will fight and not sit quietly as our members’ future is destroyed.”

Not only are 38 per cent of Lonmin’s 33,000 employees due to be retrenched within the next three years, according to Sibanye’s takeover plan. And not only did its CEO Neil Froneman immediately warn critics to cease attacking Lonmin for repeated violations of its state-mandated Social and Labour Plan: “Communities that are unhappy, the Department of Mineral Resources that is unhappy – need to stop and allow us to complete this so that in the longer-term we can do more.”

Just as importantly, Froneman’s takeover does nothing to resolve at least half a dozen underlying Resource Curses revealed at Marikana, though also witnessed to a lesser extent across the country’s ‘Minerals-Energy Complex’:

- political – the obedience of politicians like Ramaphosa and the state security apparatus to the needs of multinational mining capital;

- economic – the tendency to overproduction intrinsic to the capitalist system, especially in times of a commodity super-cycle (2002-11) whose subsequent crash left Lonmin vastly over-exposed;

- financial – usurious microfinance borrowed by mineworkers, leading to extreme borrower desperation by the time of the August 2012 strikes, and $150-million in World Bank ‘development finance’ investment;

- gendered – especially the stressed reproduction of labour and community by women in the Nkaneng and Wonderkop shack settlements;

- environmental – extreme degradation within fast-growing peri-urban slums, nearby which minerals are dug and smelted using high-carbon processes that also pollute local water, soil and air;

- labour-related –

- platinum rock drill operators’ inadequate wages and deplorable working and residential conditions, especially in comparison to mining executives’ ludicrously generous remuneration:

- the durability of apartheid-era migrancy, itself a condition dividing workers from the area’s traditional residents along familial, ethnic and (property-related) class lines;

- intra-union battles which split workers and generated some of the initial 2012 violence, followed by further violence in 2017 including within Amcu;

- and ongoing mass retrenchments due to a (failing) automation strategy and platinum gluts.

Unless there’s radical change, the industry’s future is gloomy. As Mining Review Africa acknowledged in November, “demand for platinum, used primarily in diesel-fueled vehicles, continues to take a hit from the repercussions of the Volkswagen diesel emissions scandal.” With the platinum market glutted, Froneman’s main rationale in buying Lonmin is to consolidate the firm’s relatively cheaper smelting over-capacity for use by other firms. Closure of Lonmin mine shafts will accelerate.

These factors contributed to mass strikes in 2012 (one month) and 2014 (five months), to periodic social uprisings and to ongoing discontent. Most could have been avoided had the 1955 Freedom Charter calling for socialization of mining wealth been heeded by the ruling African National Congress (ANC) after liberation in 1994. The social democratic Freedom Charter was once, after all, the ANC’s ideological bible – and always vigorously opposed by capitalists.

But when ANC Youth League leader Julius Malema again raised the demand for mining nationalisation at a 2011 conference, a party disciplinary committee led by Ramaphosa expelled him and his comrades. They subsequently founded the Economic Freedom Fighters party and won a large share of the platinum belt’s vote in subsequent elections.

The massacre shifted South African politics forever. Wrongdoing was investigated by the 2012-15 Farlam Commission set up by Zuma, but the outcome was weak and biased. It is tempting to emphasise the negligence or malevolence of personalities. Judge Ian Farlam blamed maniacal police leadership. But recall, too, that Lonmin chief executive Ian Farmer’s salary was 236 times higher than the typical rock drill operator, that his main executive replacement Barnard Mokwena was later unveiled as a State Security Agency operative, and that Ramaphosa’s financial ethics were missing in action.

Ramaphosa was implicated in a Lonmin tax avoidance scandal via his Shanduka firm’s control of the Black Empowerment partner Incwala. According to Lonmin’s lawyer, “Incwala for very many years refused to agree to the new structure” to halt a $100-million outflow to the Bermuda tax haven justified as marketing expenses. As the Paradise Papers recently revealed, Ramaphosa’s firm also retained Mauritius accounts for nefarious purposes and as chair of Africa’s largest cellphone operator, MTN, he suffered continent-wide criticism for illicit capital flight.

Resistance Rises Too

Against mining capital and the politicians stand Amcu, Sikhala Sonke, the church-based Bench Marks Foundation (which earlier this year began campaigning for Lonmin divestment), the Marikana Support Campaign, Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters, and solidarity activists in Britain and Germany. In addition to better wages and community investment, their four post-massacre demands are that Lonmin and the government publicly apologize, pay survivors and widows reparations (civil suits of more than $75-million have been filed) and declare August 16 a national holiday with a monument at the site of the massacre.

But now a much larger opportunity rises to cure the diseases that felled Lonmin, especially if Sibanye’s offer is rejected. After all, Lonmin’s nationalization at such a fire-sale price is eminently reasonable and affordable. The state should also charge the firm’s shareholders for the costs – legal liabilities and fines – of decades of misbehaviour imposed on the economy, society and the environment. Moreover, so as to lessen vulnerability to volatile world capitalist markets, it is long overdue for South Africa (with 88% of world reserves) to join Russian and Zimbabwean authorities in a world platinum cartel, about which formal discussions began nearly five years ago.

In the process, a genuinely green strategy for the region should move the economy away from overdependence upon traditional coal, iron ore, manganese, gold and diamonds exports, and ensure a ‘Just Transition’ to post-‘extractivist’ economic activities in line with South Africa’s growing climate mitigation and adaptation imperatives. As Sikhala Sonke and allies point out, the latter should be especially friendly to women’s needs, within not just the sphere of production but also the reproduction of society. As an example, the Cape Town-based “Million Climate Jobs” campaign recently produced anther booklet explaining the Just Transition process.

These sorts of visionary demands contrast with the ANC’s lowest-common-denominator ideology of neoliberal-nationalism, now that the worst tendencies of both the WMC and Zupta camps are on display within the party’s leadership. Aside from a #FeesMustFall breakthrough when Zuma promoted free tertiary education last Saturday just as the ANC congress began, it is likely that 2018 will begin with budgetary austerity and a Value Added Tax increase. Meanwhile ANC leaders will continue to talk left (so as to) walk right, with renewed preparedness for a state of emergency if socio-economic protests continue rising.

But amidst undisguised pro-Ramaphosa media bias (e.g. the popular Daily Maverick), even his corporate backers are genuinely nervous about Monday’s “poisoned chalice.” As they are now realising, “Markets got this one wrong – and were pricing in a Cyril slate victory,” failing to comprehend new dangers within the ruling party’s fusion of the WMC and Zupta factions. Durable liberal-bourgeois concerns about the new leader have also been expressed in ascerbic critiques of the “Grand Consensus“ “nothing man“ by Business Day columnist Gareth van Onselen. I once debated another liberal commentator, Richard Calland a few years ago, in which he was pro-Ramaphosa for all the wrong reasons.

Neither the ANC nor Lonmin are going to exit their respective crises in the immediate future. The notion of crisis has always implied both destruction and opportunity. Mining tycoons and political elites have generally (except in 2015) avoided the former and are now grabbing the latter. So even if the South African state under Ramaphosa’s leadership can never become a trusted ally of the left, resistance from below will no doubt expand activist horizons, the more damage Lonmin does – even now in its messy death throes.

The takeaway message is the same threat “Cyrilina Ramaposer” offered in her haunting Makarena on Marikana: “This shit ain’t over.” •