Everyone sensed the new energy at Labour Party conference this year. More cynical pundits referred to it as “giddy with optimism” (the Guardian’s editorial), or “support bordering on hysteria” (Simon Jenkins), conveying the idea of something irrational. Others referred to it as Corbyn’s “evangelical church” (Philip Collins) or even ‘the cult of Corbyn’ (the Times, Spectator and Observer all used this phrase).

The reality of the conference was something not seen in the UK for a long time: thousands of determined and self-confident members of a Labour Party that boldly stands for what they believe in. Their self-confidence stemmed not from some kind of Corbyn cult, but from the fact that they could now stand on the doorstep, or talk to their friends and family, arguing honestly and hence persuasively about why they should support a Labour government.

This self-confidence, with the political and personal energy released by working to support a party you believe in, was my experience of both the Labour conference itself and The World Transformed fringe festival (and the two cross-fertilised creatively). It was combined with the steely determination to win that is evident in, for example, the massive support for the constituency-by-constituency Unseat a Tory campaigns initiated by Owen Jones, and attendance at panels such as “How to win a marginal” being as high as for “Acid Corbynism.”

Power Beyond Parliament

Far from giddiness, I heard nothing but sobriety from the likes of Paul Mason and shadow chancellor John McDonnell. At packed meetings, they largely spurned crowd-pleasing rhetoric to explain in cold detail what a radical Labour government would be up against: not only a possible run on the pound, as the media made hay out of quoting, but a sustained investment strike and other forms of non-cooperation and sabotage on the part of capital. Ann Pettifor lucidly explained the powers the government would have through its role as the banks’ guarantor of last resort.

They listened attentively to Theano Fotiou, Syriza’s minister of social solidarity, describe the obstacles they faced in Greece as an (initially) radical party in government, including failures in Syriza’s own strategy, organisation and leadership – especially its failure to maintain the party’s engagement with and accountability to social movements.

As if learning the lesson of Greece, Brazil and indeed all other attempts by what were initially radical left parties to implement their programme as a government, McDonnell called on his listeners to organise, to mobilise and to educate – to build a popular movement that would provide both a counter-power to the hostile pressures from private business and the City, and counter-arguments to the hostile press who will exaggerate and urge on all opposing interests, attempting to divide and demoralise Labour’s supporters.

Here a distinctive aspect of the conference, perhaps symbolic of the reality of the changed Labour Party, is the way it generally overcame the traditional divisions built in to Labour’s parliamentarism. Extraparliamentary struggles and campaigns have usually been present at Labour conferences, but pushed to the fringes, while a legislative programme for the parliamentary party took centre stage. All life at conference used to be deadened by endless speeches by lords, ladies and honourable members. This time a large number of ordinary delegates got to speak, and spoke not only about policy but about action: teachers campaigning against the cuts, postal workers preparing to strike, health workers too acting against the relentless moves by private companies to break up and take over the ‘profitable’ parts of the NHS.

When they cheered McDonnell’s commitment to take back private finance initiative (PFI) contracts into the public sector, they did so not only because they supported the actions of the future Labour government but because this commitment vindicates their years of campaigning to stop these PFI deals in the first place.

Cult of Ourselves

Platform speakers too made extraparliamentary action part of their arguments. Naomi Klein used her slot as international guest speaker – formerly an opportunity for delegates to sneak out for a long cup of coffee while some disconnected notable gave an inconsequential speech – to insist not only that ‘No is not enough’, but that we should be and are creating practical alternatives out of resistance in the here and now. A packed conference chamber whooped their agreement, while across the road at The World Transformed the idea of prefigurative politics was common sense in session after session.

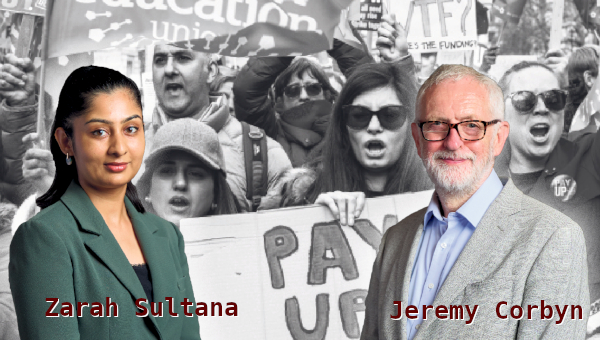

The energy at the Labour Party conference, then, reflects more than adoration of the leader: ‘Oh Jeremy Corbyn’ is meant more of a chant of encouragement than the approval of a passive fan. Even at Ed Miliband’s highly convivial and humorously conducted pub quiz, the chants of ‘Oh Jeremy Corbyn’ broke out on cue when a picture of the leader appeared in the ‘odd one out’ section of the quiz. But the spirit of self-parody is a long way from the evangelical cult that uncomprehending pundits try to conjure.

Corbyn’s insistence on the ‘we’, not the ‘me’, is taken to brain as well as heart. We must win, and we must think and act strategically to do so. We must prepare for government, and not just leave it to the future ministers. And the power of government is necessary but insufficient: we must mobilise our distinct sources of counter-power in alliance with Labour in government.

But it’s not all onwards and upwards. Though the conference had a strong sense of the prospect of a Labour government and was committed to maintain the electioneering energy built up earlier this year, there remains the problem of divisions – of MPs who not only disagree with the elected leadership, which is of course fine in a democratic party, but who still refuse to accept the legitimacy of Corbyn’s overwhelming double mandate, and continue to undermine him by stealth. While many on the centre-left accept that Corbyn’s leadership is here to stay and, contrary to their expectations, is proving electorally successful, there are others who are imbued with Blair and Mandelson’s deep contempt for the left and who do not accept they are now a minority in the party – and have plenty of friends among newspaper columnists.

Until another election period gives a left leadership equal access to the media, as happened in June 2017, the left will continue to suffer from being seen by the public through the prism of party divisions in which the right is presented by the media as morally hegemonic.

What will overcome such anti-social behaviour, short of the Asbo of triggering a reselection process, is unclear – perhaps some combination of pressure from the unions and positive, energetic electioneering by the local party shaming such MPs into supporting the party to whom they owe their job.

Like Housework, Never Finished

But such a scenario raises a further problem: of time, energy and resources for local activists, especially those organised through Momentum, as they face the multiple tasks demanded of them in the present complex and uncertain context. The priorities evident at the conference indicate that this new, new left aspires to combine electioneering with creative extraparliamentary resistance and alternatives. It refuses the either/or binaries of the past. But it refuses too a life of endless meetings, a life devoid of pleasure and reflection.

Talk to activists in any active branch of Momentum and you find they are experimenting with a new role for Momentum once the left wins the majority of positions in the local Labour Party. The struggle for effective control over the local Labour Party, however, is a bit like housework, never finished. No sooner do you complete one task, such as winning seats of the local executive committee, then another appears essential, for example the local campaign forum, controlled by the councillors whose relationship to the local party is highly mediated and only partially accountable.

Like housework it can take over your life, leaving no time for anything else – unless, that is, you create some kind of autonomous activity with its own dynamic. So with Momentum in several cases. In Bristol, for example, a large Momentum movement – that has already led to several left-run CLPs and a delegation of over 30 to conference – maintains itself as a flexible, creative space for the incubation of ideas, education, and grassroots campaigning, feeding into local parties but with autonomy from them.

This was well symbolised in Brighton by the autonomy of The World Transformed (TWT): not held in opposition to Labour conference, but with a life of its own. In this sense TWT, along with the growing infrastructure of radical left media, is helping to re-create a critical and internationalist socialist political culture that Tony Blair destroyed under his presidential ‘me’ leadership. TWT and Momentum are turning Corbyn’s ‘we’ into a living reality, with all the autonomy and creativity that such an arrangement implies. •

This article was first published by Red Pepper magazine.