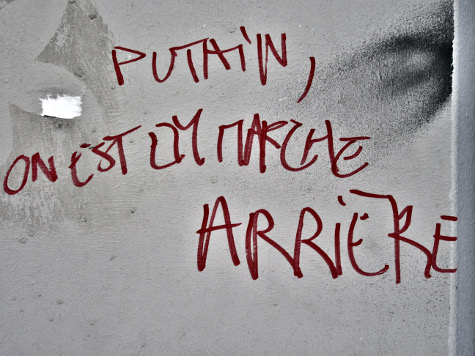

“Putain, nous sommes en marche arrière”

— Slogan on a wall in the 20th district of Paris.

“I really hope Macron can reform France, which is not doing well, you know.” These were the words of a young and stylish corporate lawyer, who started chatting with me during lunch in the cafeteria of the French national library. Emmanuel Macron‘s La République En Marche had just won the Parliamentary elections. The lawyer tried to convince me of the benefits of liberalism but also expressed anxiety about whether Macron would manage to do what previous Presidents have not: overcome all the various social and institutional obstacles in the way of a full-fledged neoliberalism.

His ambivalence captured the tone of those capitalists and financial journalists who voice cautious optimism about Macron’s capacity to restore the confidence of global investors and the European Troika in France. But, in their tunnel vision of an impossible liberal utopia, these commentators typically gloss over the thorny problem of political rule. Macron is both a symptom and cause of the current political crisis in France: a decomposition of the party system alternating between the right and the (nominally) left, reinforced by systemic uncertainty about the future of the European Union and Euro-American imperialism. This crisis is expressed most clearly by the angst-driven willingness of most French politicians to normalize rules of exception in order to bypass parliament and perpetuate the state of emergency in place since 2015.

The 2017 Legislative Elections

In the second round of the French legislative election, newly-elected President Macron’s ad hoc political formation En Marche managed to win 308 seats in the French National Assembly. While less than the predictions made after the first round, this is an absolute majority of the 577 seats in the Assembly. Given the comparatively low percentage of the vote En Marche managed to gather in the first round of the legislative elections (32.2%), this result was made possible by France’s two-stage majoritarian electoral system. Macron’s majority increases further (to 350) if one counts the 42 seats won by Francois Bayrou’s centrist MoDem (Mouvement Démocratique), with whom Macron struck an electoral agreement.

Compared to Macron’s and Bayrou’s success, France’s other political formations suffered major setbacks. While the bourgeois right – Les Républicains (LR) and Union des Démocrates et Indépendents (UDI) – was not decimated, its combined seat total shrank to 136, compared to 196 in 2012 when they lost their parliamentary majority to Parti Socialiste (PS). This defeat has already prompted a formal split. 38 centre-right politicians from the LR and the UDI have formed a separate, ‘Macron-compatible’ parliamentary group willing to work with the new majority.

The Front National failed, once again, to translate promising results in the Presidential election into real parliamentary weight. While they increased their presence in the Assembly to 8 seats, this is still not enough to form a parliamentary group. As a result, internal struggles over the direction of the party, which resurfaced after Marine Le Pen’s defeat by Macron in the Presidential election, are sure to intensify in the near future. Will Le Pen and chief strategist Florian Philippot’s already weakened line (a critique of the EU, the old fascist slogan ‘neither left nor right’) hold against those who want to re-situate the FN more decisively on the extreme right, with even fewer ideological concessions to economic sovereignty and social questions, and forge a strategy to begin collaborating formally with the populist wing of the LR?

The left, meanwhile, was reduced to a strikingly low overall proportion of the Assembly – 12.6% of all seats. Since 1981, when the PS and the PCF won the elections, the left dipped this low only once, in 1993 (16.1%). Otherwise, the total proportion of the left fluctuated between 30.9% and 67.8% in that time period. So what explains their recent performance? Simply speaking, the Socialist Party (PS) and the Greens (Europe Ecologie/Les Verts) received the bill for the disastrous François Hollande years. The PS lost 250 of its 295 seats in the pre-election Assembly. The Greens, which won 18 seats and formed a parliamentary group for the first time in 2012, were shut out entirely.

The two left formations that did not participate in the Hollande government – the Parti Communiste Français (PCF) and Jean-Luc Mélenchon‘s France Insoumise (FI) – fared better, with 10 and 17 seats respectively. The PCF and the FI (which ran under the common banner of the Front de Gauche in 2012) failed to reach an electoral agreement prior to the first round, after which many of their candidates were eliminated and thus could not capitalize on Mélenchon’s promising result. Despite this failure, which many grassroots organizers deplored bitterly, the PCF and the FI managed to increase their total number of seats from 15 to 27, the total of the Front de Gauche in 2012. The weight within the (now much diminished) parliamentary left has shifted to the left of the Socialists in ways unseen since the 1970s. This puts the Mélenchon’s FI in an enviable position when it comes to discussions about a potential recomposition of the parliamentary left in France.

A New Ruling Bloc?

Bruno Amable and Stefano Palmobarini have pointed to a persistent feature of French politics since the late 1970s – the difficulty of forging a neoliberal social bloc with relatively predictable electoral capacities. They argue that the social components of a potential ‘bourgeois bloc’ (factions of the bourgeoisie and its upper-middle class allies) have been torn between the major forces of left and right, the Socialist Party, and its right-wing equivalent (which changed its name a few times, from the RPR to the UMP and now the LR). In this context, Macron’s En Marche, built as it was upon the marginalization of the PS left under the Hollande-Valls-Macron leadership and the subsequent implosion of the PS as a whole, promises to liberate neoliberals in various camps from what remains of the already greatly weakened left-right social and ideological cleavage. These shackles have stood in the way of a French version of British Blairism or a German-style Grand Coalition.

Amable and Palombarini’s neopluralist (and neo-institutionalist) analysis is too mechanical (treating alliances as static aggregates of pre-existing social interests) and too idealist (abstracting from the contradictions and struggles which, in a capitalist context, corrode ruling blocs). It is also one-sided in neglecting other political forces central to French politics. For example, they ignore what Sadri Khiari has called the colonial counter-revolution: France’s response to decolonization, Third World aspirations, and migrant mobilizations since the late postwar period. Still, Amable and Palombarini provide a welcome, longer-term context for all those who have written about the crisis of rule in the current conjuncture. They show that hegemonic instability in France (as posited by Stathis Kouvélakis), which has indeed intensified under Sarkozy and Hollande, builds upon deeper cracks in the foundation of bourgeois rule in France.

Amable and Palombarini also provide proper context to what Gramsci would call Macron’s ‘transformism’ – his capacity to absorb or neutralize elements of existing parties (Socialists, centrists and liberals) while also recruiting people without strong ties to these political formations. Some of this capacity results from painstaking labour (undertaken by many, including Macron’s wife Brigitte Macron) building social ties between their own provincial worlds and Parisian bourgeois circles. Thus embedded, Macron’s government and the newly elected parliamentary group En Marche could become a key component of a new ruling bloc, one that links a new cross-partisan mix of politicians and operators to new political recruits. It would be a bloc, therefore, that is younger, more entrepreneurial, a bit more female, and less beholden to the interpersonal feuds and sectarian allegiances that have immobilized existing political apparatuses.

A Thin Majority

Macron’s rapid rise from the senior state bureaucracy to President (via banking and the Hollande government) may turn out to be too good to be true. Three days after the Parliamentary election, Macron already had to regroup his government. Four ministers and state secretaries, including MoDem chief Bayrou, had resigned from cabinet. They had run afoul, individually or through their party MoDem, of a top Macronite electoral promise: to bring moral integrity to public office, a promise which Bayrou himself was charged with implementing. Like the Front National, MoDem is being investigated for using the labour of EU Parliamentary assistants paid by Brussels to support their national party apparatus instead of the work of their European deputies. Clearly, Macron’s image of political renewal is already tarnished by ‘old’ practices. Given that links between business and government are particularly systemic in Macron’s regime, these resignations are unlikely to remain the only ones in his term.

Macron himself is split between two contradictory orientations. While declaring the renewal and broadening of the French ruling class, he enthusiastically supports the deeply undemocratic features of the Fifth Republic – the heavy bias toward the office of the President, which lends itself to personalized rule and curtails Parliament in several acute ways. Macron has admitted to his (quasi-)royalist, or, perhaps more accurately put, Bonapartist leanings. These leanings are now infused with the business-oriented managerial practices that permeate Macron’s government and the enthusiasm by which Macron extends France’s imperial foreign policy, pushing for a proper EU security and military apparatus while sustaining France’s military missions in Africa.

Authoritarianism is indeed second nature to Macron. After prolonging the state of emergency for a sixth term, he has already embarked on a project to enshrine in regular legislation key provisions of the state of emergency law, including pre-emptive house arrest, house searches, the closure of places of worship (i.e. mosques) and a newly added provision to define zones where police have special powers to search people and property. He thus proposes to make permanent the very rules of exception that undermine basic principles of the separation of powers and habeas corpus. These have been used during the Hollande years not primarily to pursue perpetrators of terrorist attacks but more frequently to criminalize Muslims, residents of segregated neighbourhoods, and protestors of police violence, climate change and labour laws.

Macron’s strategy to radicalize Hollande’s record (which he himself carried to a significant extent) has a second, closely related plank: his promise to accelerate the deconstruction of France’s social security system, shrink the public sector, and deepen labour law reforms to further buttress the power of employers in various ways. One such way is to decentralize collective bargaining to the enterprise level, thereby undercutting the capacity of French labour unions to compensate for very low unionization rates with sector-wide strategies or national political action. As Amable and Palmobarini have pointed out, there is no social majority for such reforms in France. The modernizing, so-called social-liberal wing of the Socialist Party, and the neoliberal currents in the French centre and right (both of which Macron draws upon), have faced this resistance repeatedly since the 1980s. Under Hollande, this lack of solid social and parliamentary support for economic liberalism explained the recourse to constitutional mechanisms to bypass Parliament and new levels of repression to curtail and divide mass protests.

Macron’s strategy to radicalize Hollande’s record (which he himself carried to a significant extent) has a second, closely related plank: his promise to accelerate the deconstruction of France’s social security system, shrink the public sector, and deepen labour law reforms to further buttress the power of employers in various ways. One such way is to decentralize collective bargaining to the enterprise level, thereby undercutting the capacity of French labour unions to compensate for very low unionization rates with sector-wide strategies or national political action. As Amable and Palmobarini have pointed out, there is no social majority for such reforms in France. The modernizing, so-called social-liberal wing of the Socialist Party, and the neoliberal currents in the French centre and right (both of which Macron draws upon), have faced this resistance repeatedly since the 1980s. Under Hollande, this lack of solid social and parliamentary support for economic liberalism explained the recourse to constitutional mechanisms to bypass Parliament and new levels of repression to curtail and divide mass protests.

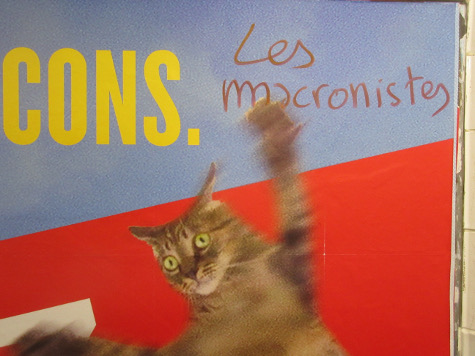

The project of building a more integrated socio-political bloc to sustain Macron’s liberal political synthesis is thus fraught with deep obstacles. Everyday entrepreneurialism has made headway among the French population, including in segregated neighbourhoods with non-white majority populations. Yet this daily entrepreneurialism, which is sometimes a matter of survival and an obvious feature of social media dynamics and mass-produced pop culture, does not in itself indicate a widely shared, deeply held and unequivocal commitment to neoliberalism. Many indications, including surveys and exit polls, suggest that Macron’s Presidential and Parliamentary majorities do not reflect a profound appeal of his ideas or programme.

Macron won the elections to a large extent because French voters rejected his opponents (the PS, the right, and the Front National) and withdrew from elections on a mass basis. In the second round, 57.4% of registered voters refused to cast a ballot, a rate that exceeds the record set in 2012 by a whopping 13.7%. 440 of 577 deputies were elected by fewer than 25% of registered voters. If one takes into account rates of non-registration, Macron’s support drops even further. In the first round, when people could choose from the full range of parties, less than 11% of eligible voters cast a ballot for En Marche. The party of abstention, not Macron, was the winner of the 2017 vote. In contrast to the UK, where Jeremy Corbyn’s campaign was carried by a remarkable surge in participation by young people, the electoral behaviour of French citizens, particularly the young and members of the working class, is more volatile than ever.

Macron 2017 = Le Pen 2022?

As Emmanuel Macron faced Marine Le Pen in the second round of the Presidential election, a slogan started appearing on the walls of central Paris: Macron 2017 = Le Pen 2022. This equation underestimated the dangers of the Front National. Yet it still has the great propagandistic merit of establishing a relationship between neo-fascism or authoritarian populism and less openly nationalist and socially conservative forms of neoliberalism. This relationship has been endemic to Euro-American politics since the 1980s. The ongoing instability of political rule, widespread social precarity, and an embrace of imperial war and anti-Muslim racism by liberals, centrists and Socialists suggest Macronism will indeed further fertilize the ground for the Front National and its potential future allies on the populist Sarkozyist or Catholic right.

It is important not to forget another key fact from the 2017 French elections: the Front National established itself for the first time as a party that could win the Presidential election. Within a week of the run-off vote, Marine Le Pen polled within 18% of Macron. At the end, she garnered 34%, not 41% of the vote. Still, a record 10.6 million French voters cast their ballots for Marine Le Pen, almost twice as many as the 5.5 million (17.8%) who voted for her father in 2002. Marine Le Pen’s result builds upon the FN’s record-breaking results in the European and municipal elections of 2014 and 2015. The FN’s relatively weak performance in the two rounds of the Legislative election (13.2% and 8.8% respectively) thus does not mean that the FN is on its way out. In fact, the election has shown that it is more difficult now than at any other time since the FN emerged on the electoral scene in the early 1980s to contain the spread of the party.

In the end, left and popular-democratic forces are the only ones with the potential to break the link between Macron and Le Pen. Crucial questions impose themselves in this context.

- Will the organized, parliamentary or non-parliamentary left undergo a process of recomposition to avoid further marginalization and fragmentation?

- Will the forces who have confronted Hollande and Macron’s labour law reforms in the street (for example the union activists and autonomists in the newly formed Front Social) muster the energy to defeat Macron on this point and the broader austerity agenda, the divisions in the labour movement notwithstanding?

- Will the coalition that managed to pull off an impressive mass march against racism and police violence on March 19 build on its efforts?

- Will it be feasible to mount a significant resistance against the normalization of the state of emergency proposed by Macron, a normalization that is keeping far-right demands to permanently and pre-emptively intern the ‘radicalized’ alive?

- Finally, will it be possible, in this broader context, to focus anti-fascist energies (yes, on the FN and the galaxy of fascist groups surrounding it, but also), as Saïd Bouamama has urged repeatedly, against the acts of everyday violence (against burkini-wearing Muslim women, Roma campers, or refugees) which have helped implement, as it were, racist and Islamophobic policies while legitimizing the FN? •

Stefan Kipfer was on sabbatical leave in France at time of writing.