With U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to formally withdraw from the Paris Agreement, he has put an end to months of apparent indecision. This withdrawal does not dissolve the agreement, which still includes nearly every country on the planet, but it is hard to imagine how an already weak agreement can be expected to slow – not to mention reverse – greenhouse gas emissions without the participation of the United States. Seeing this decision as anything other than a nail in the coffin of the global climate regime is nothing but wishful thinking.

For an administration that has promoted a seemingly unending series of bad policies – from healthcare to immigration to militarism to the unceasing transfer of wealth from working people to the wealthy – this may be its worst. When future generations look back at the harm done by this president, they may remember this as his greatest crime. This is not to minimize the damage of his other policies or of the racism, xenophobia, and misogyny that drove his campaign and brought him into the White House, but climate change is the ultimate issue. It will affect everyone while exacerbating existing inequalities, and we only have one chance to get it right.

For an administration that has promoted a seemingly unending series of bad policies – from healthcare to immigration to militarism to the unceasing transfer of wealth from working people to the wealthy – this may be its worst. When future generations look back at the harm done by this president, they may remember this as his greatest crime. This is not to minimize the damage of his other policies or of the racism, xenophobia, and misogyny that drove his campaign and brought him into the White House, but climate change is the ultimate issue. It will affect everyone while exacerbating existing inequalities, and we only have one chance to get it right.

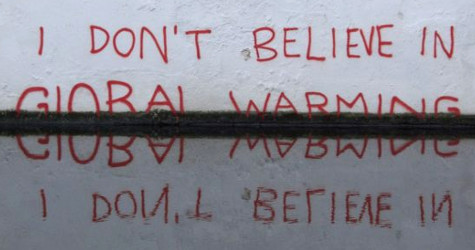

This decision is no surprise. Throughout his campaign, Trump promised to pull out of the Paris Agreement as part of his “America First” agenda that pits the promise of domestic jobs against environmental protections and international cooperation. We must reject Trump’s noxious brand of nationalism and climate denialism. It is critical, however, not to sugarcoat the nature of much of what passes as international cooperation. So-called trade agreements have benefitted corporations and the wealthy at the expense of working people both in the United States and abroad.

It is not, as Trump’s nativist critique would have it, that the United States made a bad deal with Mexico when negotiating NAFTA. Rather, elites in the United States, Mexico, and Canada made a good deal for themselves at the expense of the citizens of each country. Still, working people understand what NAFTA did to their workplaces and their communities, and Trump’s attack on trade deals may have helped him to win enough working-class support in critical states to shift the electoral map in his favor, even if the extent of his working-class support has been greatly overstated by centrist commentators.

Two Bad Paths

Despite Trump’s campaign promise to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, he waffled on the decision for several months. Upon assuming the presidency, powerful interests began urging him to remain part of the accords. At first glance, this may seem to be a case of Ivanka Trump’s supposedly moderating influence. Could there be a kinder, gentler Trumpism that recognizes that putting America first does not need to mean putting the environment last? Alas, no. While the voices advocating that the U.S. remain in the agreement are myriad, does anyone think that environmental groups, European leaders, or Democrats in Congress are likely to sway Trump’s position?

But when ExxonMobil, Secretary of State (and former ExxonMobil CEO) Rex Tillerson, and Energy Secretary Rick Perry advocate remaining in the accord, we can expect Trump to consider their perspective. These Trump allies support his agenda of dismantling environmental protections, but they recognize that by keeping “a seat at the table” and demanding renegotiations, they can undermine the agreement from within, without incurring the diplomatic repercussions of a formal withdrawal.

Trump’s waffling, then, was not between a pro-climate agenda and an anti-climate one. Rather, the indecision was on the level of strategy on how best to dismantle environmental regulations. Trump has made it abundantly clear that he plans to dismantle all Obama-era environmental protections. Indeed, his push to revoke the Clean Power Plan makes it clear that a Trump administration has no intention of meeting the commitments made in Paris.

Still, as with so much else under this administration, in choosing between two bad paths, Trump chose the worst one. A recalcitrant United States that fails to live up to its international obligations is nothing new, but this withdrawal will provide cover for any number of countries to follow the United States out of the agreement. Breaking apart whatever tentative consensus was reached in Paris will have as yet unknown repercussions long after Trump leaves the White House.

This withdrawal has serious consequences for other international agreements as well. For the United States to precipitously exit an agreement that was decades in the making leads to a loss of trust, undermining the existing international order and damaging the prospects for future multilateral agreements.

A Worse-Than-Nothing Agenda

While the decision to leave the Paris Agreement is disastrous, we should not fool ourselves into believing that this accord was anywhere near adequate for addressing the climate crisis. Even if fully implemented, the national commitments would only slow the increase in greenhouse gas emissions. They would not reduce these emissions at all, much less at the level demanded by science.

Moreover, the preferred policy mechanisms of the Paris Agreement – such as emissions trading schemes – will deepen private control of energy and extend the reach of the market, making it more difficult for the public sector to implement the kinds of changes that would foster an energy transition that does not take place on the backs of workers, racialized minorities, women, and other vulnerable communities.

So let’s not join the once self-congratulatory global elite as they mourn their dubious achievement. Still, it was better than nothing, which would be faint praise in ordinary times, but we are not living in ordinary times.

Trump is promising a worse-than-nothing agenda. Do we need to look farther than EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt to see what is in store for climate and environmental protections? Here is someone who, as Oklahoma Attorney General, dissolved his office’s Environmental Protection Unit and has consistently used the power of this office to fight the EPA and environmental regulations across the board. Is it any surprise that he has raised enormous amounts of campaign funds from the oil and gas industry over the years? This is a case of the foxes taking over the henhouse only to tear it down.

The Paris Agreement, the Clean Power Plan, and other environmental policies put in place by the Obama administration – and which a Clinton administration likely would have continued – hardly represent a radical agenda. Indeed, as mentioned above, these policies are inadequate to address the crisis. Moreover, many corporations (including entire sectors of the economy) and unapologetically pro-capitalist world leaders (from Chinese President Xi Jinping to German Chancellor Angela Merkel) support such policies – and would indeed support much stronger policies to transition to a low-carbon future.

The conflict we are witnessing here is taking place within the capitalist class, with the most voracious members of this class – chief among them the fossil fuel industry – standing in opposition to more “progressive” capitalists, such as those in the technology sector. Trump, needless to say, has become the mouthpiece for the most vicious and extreme capitalists, leading us toward a radically extractivist and authoritarian neoliberalism. Clinton, Obama, and their allies represent the more progressive side of neoliberalism, leading us toward a green capitalism. Two bad choices, to be sure, but let’s not pretend they’re equivalent.

The change we need is not going to come from politicians. With climate – as with so much else – resisting Trump’s agenda requires a different approach. There is an emergent climate justice movement that insists on putting those who are most affected by climate change first and that brings together communities on the frontlines of resistance with indigenous people, environmentalists, trade unionists, and so many others. Initiatives like Trade Unions for Energy Democracy, for example, have, built a global community of union leaders who are working to advance real solutions to the climate crisis, ones which reflect democratic will and which operate in the public interest. From remunicipalizing local energy grids to blockading new fossil fuel infrastructure, the possibilities for action are endless.

The damage that Trump is doing cannot be understated, but no matter who the President of the United States is and no matter what global agreements are crafted at the United Nations, we need to build a movement that is big enough, creative enough, and radical enough that it cannot be ignored. As the People’s Climate March insisted, “to change everything, we need everyone.” •

This article first published by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.