“You never want a serious crisis to go to waste.”

— Rahm Emanuel

Saskatchewan’s 2017 budget landed with an unenthusiastic thud last week. Riddled with cuts, job losses, public sector wage reductions, and tax increases, the Saskatchewan Party’s austerity budget has garnered few friends, with critics ranging from organized labour movement to small businesses.[1] The government’s budget has several fiscal goals: aggressively tackle its $1.3-billion deficit in three short years, overhaul the tax structure away from progressive forms of taxation to consumption taxes, and dismantle key aspects of the social welfare state.

In our view, Budget 2017 should be viewed in two ways. First, it is clearly a reactionary document drafted by an openly conservative government responding to the dramatic fall in natural resource prices that began in 2014. Second, and perhaps equally important, the budget is also a calculated political decision to exploit the fiscal crisis to further transform the provincial state to facilitate long-term private capital accumulation in the natural

In our view, Budget 2017 should be viewed in two ways. First, it is clearly a reactionary document drafted by an openly conservative government responding to the dramatic fall in natural resource prices that began in 2014. Second, and perhaps equally important, the budget is also a calculated political decision to exploit the fiscal crisis to further transform the provincial state to facilitate long-term private capital accumulation in the natural

resource sector, keeping those sectors free from a burdensome tax regime or regulatory pressure. In other words, the government is using the fiscal crisis to push through the so-called “Saskatchewan Advantage,” which it defines as the province having “the lowest corporate tax rate and the lowest tax rate on manufacturing and processing in the country.”[2]

Although the extension of such neoliberal policy initiatives has long been promoted by the Saskatchewan Party, the crisis of 2014-2017 has provided the government with both the economic and political opening to further dismantle important aspects of the social welfare state, attacking public sector workers (while undermining public sector bargaining) and further privatizing the public enterprises that define Saskatchewan’s mixed public-private political economy. In other words, the government has taken full advantage of the deficit and stagnant commodity prices in order to fulfill its long-held ideological objectives.

Building the “Saskatchewan Advantage”

Since its election in 2007, the Saskatchewan Party has governed the province through a mixture of moderate right-wing economic policies combined with ruthless contempt for workers’ collective rights to bargain or strike, especially in the public sector. Between 2007 and 2014, that formula proved incredibly successful for the government as it presided over an unprecedented economic boom driven by record high commodity prices, especially in the oil, gas, and potash industries. This allowed the government to pay for increases in spending and tax cuts through royalty revenues. To be sure, the Saskatchewan Party inherited this boom and economic growth from the previous NDP government, along with the relatively low royalty regime it had crafted. While much of Canada was still suffering from the effects of the 2008 economic collapse, Saskatchewan’s commodity boom handed the government a series of structural benefits that it never tired of reminding voters: between 2009 and 2014, the population of the province grew by 8.7 per cent, pushing the population of the province over the 1.1 million mark, while unemployment remained at record lows.

Throughout the boom, the Saskatchewan Party’s fiscal priorities were to maintain existing social services while quietly transforming the internal culture of the public service. To be sure, certain areas of the public service saw annual increases in public funding although

most services outside of health were funded at or just above the rate of inflation. Yet, the broader public service was subjected to restructuring through a reduction of the “overall footprint of government” asking the public sector (and workers in the health and education field in particular) to “consider how programs and services can be made more efficient and effective and how we might get by with less.”[3] To meet this goal, the government set out to reduce the size of the public service by fifteen per cent, while imposing similar restructuring on the province’s Crown corporations. Those changes introduced in 2010-2011 resulted in a leaner public service and laid the ground work for the full (if failed) implementation of “lean” management in the healthcare system.

Alongside changes in the public sector, the Saskatchewan Party has also engaged in a series of pro-market economic policies to quietly restructure important aspects of the state. The government has fully embraced public-private partnerships (P3s) in building important

infrastructure partnerships, which includes highways, hospitals, and schools. The government also engaged in a series of large and expensive infrastructure projects that included the $1.2-billion Boundary Damn carbon capture facility, a multi-billion-dollar road project around Regina (which is bogged down in land scandals tied directly to the Saskatchewan Party) and a publicly funded football stadium. As the Saskatchewan branch of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives has shown, the party has also been active in privatizing government assets, although it had done so largely on the margins until 2014 when the government announced it was open to privatizing public liquor stores.[4]

The Saskatchewan Party also has engaged in a decade-long attack on organized labour through a series of regressive changes to labour law in the province. While some of that legislation was struck down by the Supreme Court, which handed workers the constitutional right to strike in 2015, amendments to the Trade Union Act (now the Saskatchewan Employment Act) have made organizing exceedingly cumbersome, work stoppages difficult to commence, streamlined the decertification process, and weakened successor rights in the event of subcontracting or outsourcing. Put simply, the government constructed a new labour law regime that would allow it to more effectively confront union opposition in the event of an economic downturn.

Furthering the “Saskatchewan Advantage”: Budget 2017

While the Saskatchewan Party’s fiscal policies throughout its tenure have certainly been openly neoliberal, its embrace of public sector austerity had been restricted by structural factors contributing the commodity boom. In fact, investments in public services and

infrastructure continued because of commodity revenues. Elected with exceedingly large majorities in 2011 and 2016, the Saskatchewan Party maintained stable economic policies, fearful of upsetting the conditions contributing to the boom. The steady-hand approach

partially explains why the government refused to change the royalty structure for the discovery or extraction of non-renewable resources or to create a sovereign wealth fund to protect resource wealth over time. Yet, the province’s overreliance on revenue from the resource extraction sectors left it particularly vulnerable to the inevitable drop in global commodity prices. When those prices began to drop in 2014-2015 the government was left with a significant fiscal hole, although it conveniently delayed disclosing that fiscal reality until after the 2016 provincial election.

Immediately following the election, the government introduced a piecemeal budget that hinted the hard “transformative” changes would be punted to the 2017-2018 fiscal year. By declaring a fiscal emergency, the government was then able to impose the conditions of these changes that finally came to fruition in Budget 2017. Further announcing that “everything was on the table,” the government was signaling both to its supporters and critics that 2017 was going to be different from its previous Saskatchewan Party budgets. What followed was seven months of what we can only describe as “government by trial balloon,” where the Saskatchewan Party floated reactionary policy after policy, which included the elimination of elected school boards (which was scrapped after public backlash), the centralization of healthcare regions (which was eventually adopted), raises in flat consumption taxes, cuts in services, contracting out or firing large portions of public services, selling the Crown Saskatchewan Telecommunications (SaskTel) (which was given additional fuel when the government introduced Bill 40, The Interpretation Amendment Act, creating a new definition of privatization to sell up to 49 per cent of existing Crown Corporations without holding a referendum) or even the creation of a sovereign wealth fund. In truth, there are few who believed that everything was indeed on the table, as the Saskatchewan Party trial balloons always came back to a simple priority: austerity.

Social Role for the State?

As a governing philosophy, austerity is not simply about controlling over spending by governments. Rather, austerity seeks to alter the relationship between citizens, governments, and markets. As Donna Baines and Stephen McBride have persuasively argued, austerity is about “shrinking the social role of the state,” reducing the redistributive aspects of government in favour of market forces.[5] Recognizing how powerful austerity has become in the neoliberal period, there is enough comparative evidence to outline the basic austerity model, which includes, as McBride demonstrates: “spending reductions, supplemented in some cases by selective tax increases (for example, consumption taxes, broadening tax coverage and closing certain tax loopholes)” that are accompanied by cuts to social services that redistribute wealth, combined with “measures to enhance labour market flexibility, in the name of making the economy more competitive.”[6] When examining the 2017 Saskatchewan budget against the austerity model, its sheer lack of originality and long-term policy goals come into sharper focus.

Although the 2017 budget was released on 22 March, Premier Wall decided to bypass the legislature on Monday before budget day, announcing on Facebook that the government was going to raise the provincial sales tax (PST). Later in the media scrum, the Premier reiterated that the fiscal crisis had indeed created an “opportunity” to lessen the government’s reliance on natural resource revenue for its operating funds. The premier’s announcement came after the government had already announced that it was demanding a 3.5 per cent wage roll-back for all public-sector workers (which is arguably unconstitutional) and that it was going to contract-out custodial services, resulting in the termination of 250 low-paid workers. Central Services Minister, Christine Tell, cruelly noted that laying off these workers represented, in the eyes of the government, an “excellent opportunity for the Saskatchewan business community.”[7]

After these callous announcements, Finance Minister Kevin Dougherty finally released the budget touting the “Saskatchewan Advantage.” Announcing that its number one fiscal priority was to bring the budget to balance in three years, the government revealed an increase of almost $1-billion in new consumption taxes. Amongst the many changes was the raising of the PST by a single percentage point, while also closing numerous exemptions to the tax. Those exemptions included children’s clothing, fuel for farmers, construction labour, and restaurant meals. While some money ($34-million) was put aside to offset the PST changes there is no denying that this tax shift represents a flat tax that punishes workers and the poor far more than the wealthiest citizens. Coupled with the PST changes were one per cent cuts (over two years) to business and to progressive personal income taxes, further easing the tax burden on businesses while disproportionally benefiting those with more wealth.[8]

Budget 2017 also announced that the government was eliminating the Saskatchewan Transportation Company (STC), a provincial bus service,

whose 27 routes serviced urban and rural citizens. Founded in 1946, the STC has long-serviced urban and remote areas of the province as a cross-subsidized publicly-owned and operated enterprise. That decision laid off 224 workers while cutting off a vital transportation route for workers and low income earners, connecting rural and urban Saskatchewan. Alongside the layoffs and the $250-million it planned to save through still non-negotiated wage roll-backs (although wage reductions have already been imposed on out-of-scope public servants), the government continued with its plan to amalgamate the various health regions into a single provincial unit. While the government allocated a 0.7 per cent increase in health funding (which will not meet the rate of inflation by the end of the year) the budget also announced the partial privatization of long-term care facilities. Despite appeals from urban municipal leaders, no funding was provided for the widely successful Housing First initiatives currently in operation in Saskatoon and Regina.

The budget was also silent on environmental initiatives or addressing reconciliation issues with the province’s Indigenous communities. The Saskatchewan Party also announced that it was increasing the social services budget by a surprising nine per cent ($73-million) (although funeral services for recipients were cruelly cut). When asked about the increase, however, Minister of Social Services, Tina Beaudry-Miller echoed the traditional contempt for social service recipients, stating that many programs would be cut and that the Ministry’s job would be to further take “able bodied” out of the system and put them back into the labour market.[9] In our view, the growth of consumption taxes and winding down of certain tax exemptions could easily offset the benefit increases some social assistance recipients might receive in this budget.[10]

Perhaps the budget’s most dramatic cuts occurred in education, as the Saskatchewan Party reduced education funding by 1.2 per cent and decreased funding for universities and colleges by a further 5 per cent, which the President of the University of Saskatchewan called

the largest single cut in its hundred-plus year history. For the University of Regina alone this amounts to a cut of nearly $6-million. Government austerity measures also resulted in massive cuts to provincial funding for libraries, with Saskatchewan’s two largest cities being hardest hit. In a startling moment of shortsightedness, Minister of Education, Don Morgan remarked that the government “should be getting out of bricks and mortar libraries.”[11] Coupled with what amounted to a 55 per cent cut to the province’s library system, these changes will certainly weigh heavy on students and low income earners, with the inevitable decline in education services in the classroom while also leading to significant increases in post-secondary tuition.

Laying out substantial cuts to education, libraries, and healthcare while also drastically restructuring the tax system did not stop the government from prioritizing its previous fiscal plans, which included $1.6-billion for the Saskatchewan Builds capital plan.

Created in 2012-2013, Saskatchewan Builds (SaskBuilds) is designed to plan and manage large-scale ($100-million or more) infrastructure in the province. Consistent with the Saskatchewan Party’s ideology, SaskBuilds is mandated to fund new infrastructure projects through traditional or alternative financing. In its first report in 2012, SaskBuilds confirmed that all new infrastructure planned for the province would be “alternative” in nature, and include P3 “opportunities.” To this end the Saskatchewan Party’s “transformative change” agenda has been effectively forced upon municipal levels of government as well.

Although the revenue sharing formula that shapes the Municipal Operating Grant (MOG) allocated to cities remains intact, the province’s decision to discontinue SaskPower and SaskEnergy payments in lieu of property taxes has created massive shortfalls in

municipal budgets. These payments compensate for the fact that Crowns are exempt from paying property taxes to local governments. For Saskatoon and Regina this will leave an estimated $11-million hole in their respective budgets, forcing these governments to make tough decisions about service levels and taxes.[12] To put this in perspective, between 2011 and 2015, Crown Corporations returned approximately $102-million in revenue to the provincial capital city as grants in-lieu. Furthermore, municipal rate-payers will see significant increases to the education portion of their property taxes – which is set by the provincial government – just as funding for education has been cut.[13] What this means is that local governments must not only find ways to cope with the increasing downloading of costs without added sources of revenue, but they must now also share in the political backlash that will undoubtedly accompany increasing taxes and reduced levels of services. “Transformative change” is effectively being thrust upon all political levels of government, like it or not.

Challenging the “Saskatchewan Advantage”

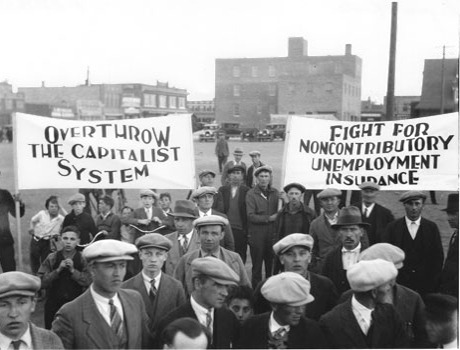

To date, opposition to the Saskatchewan Party has been largely waged by organized labour in response to wage reductions, job losses, and changes imposed upon the province’s labour relations system. Notwithstanding a large labour organized demonstration outside the legislative assembly on 8 March, throughout the Saskatchewan Party’s tenure, many of these struggles have been largely legal in nature and have not mustered serious community mobilization and rank-and-file activism. But now, with austerity and tax measures that will

undoubtedly impact small towns and rural areas, the terrain of struggle might be shifting. With the amalgamation of health regions on the horizon, the winding down of the STC, cuts to education and libraries, and potential threats to municipal service levels, the space for broader opposition to austerity has widened.

Recent initiatives like SaskForward, which formed in 2017 as a means of constructing an alternative vision of “transformational change,” have brought together a coalition of civil society groups to work on charting a different political path for Saskatchewan. The Saskatchewan Federation of Labour has launched the Own It! campaign, designed to reach out across the labour movement to build a larger fight-back strategy and Unifor, CUPE, SEIU-West and SGEU have been vocal critics of the Saskatchewan Party’s austerity agenda. Equally promising is that the Fight for $15 and Fairness movement that has been growing across North America has surfaced in the province. Meanwhile, the Saskatchewan Teachers Federation (STF) has remained virtually silent as their members face layoffs and significant funding cuts. Adding teachers to the chorus of anti-austerity efforts could create conditions for mass demonstrations against the government not unlike Ontario’s Days of Action. If the Saskatchewan Union of Nurses (SUN) were to add their significant influence to the struggle by joining forces with healthcare unions already engaged in the fight, we are convinced that the movement would be a formidable obstacle to the government’s austerity agenda.

What is required now is the capacity to bridge public sector austerity and labour struggles with the conditions of employment and poverty facing low-wage workers and sectors in Saskatchewan. There is also a need for engagement with the growing number of refugees, migrant workers, and immigrants that call the province home. Anti-colonial, anti-racism, and feminist struggles combined with environmental justice also need to become a mainstay of community mobilization. This must be done with a focus on enacting change at the local and

provincial levels of government. Most importantly, it’s critical that this energy is channeled into community-based movements, and not partisan political action alone. Recognizing that the NDP’s time in government during the 1990s and 2000s was defined by its own brand

of austerity should not be forgotten. Now is the time to create a broader, inclusive, and democratic alternative to the austerity driven “Saskatchewan Advantage.” •