Matteo Renzi assumed the role of Italian Prime Minister on February 22, 2014 as the self-proclaimed rottamatore – the ‘demolition man’ of an inefficient system. After

successfully passing a series of laws by means of this very system that lowered social standards, he failed in the attempt at a constitutional amendment that would have accelerated future measures designed to further degrade social standards. In a referendum held on December 5, 2016 a clear majority of 59 per cent rejected the proposed changes. Renzi held on to pass the 2017 budget through parliament but then resigned on December 7. Since then, ex-foreign minister Paolo Gentiloni has taken charge of government affairs.

New elections demanded by the opposition after the failure of Renzi’s constitutional reform are not in the cards for now. There is also no more talk about an imminent collapse of the Italian banking system and a resulting flare up of the euro crisis. In the weeks prior to the referendum media warnings came fast and thick that failure to approve the constitutional amendments would lead to a severe economic crisis. At the same time interest rates and capital flight increased drastically.

New elections demanded by the opposition after the failure of Renzi’s constitutional reform are not in the cards for now. There is also no more talk about an imminent collapse of the Italian banking system and a resulting flare up of the euro crisis. In the weeks prior to the referendum media warnings came fast and thick that failure to approve the constitutional amendments would lead to a severe economic crisis. At the same time interest rates and capital flight increased drastically.

Palace Revolutions

A similar development took place in the autumn of 2011. In September of that year, a letter from former ECB president Jean-Claude Trichet and his designated successor Mario Draghi to Italian PM Silvio Berlusconi leaked out, in which Berlusconi was called upon to undertake a decisive reorganization of the Italian national budget.

At that time massive increases in interest rates raised the cost of refinancing the accrued debts of the Italian state. Berlusconi stepped down on November 9. His successor Mario Monti assembled a governing team of unelected technocrats and announced radical cuts. Interestingly, this was accomplished via the legal framework for such measures created by Berlusconi beforehand – the relevant law was passed on September 8. The letter from Trichet and Draghi that urged Berlusconi to take the measure was dated August 5 and published in the press on September 29.

Tribunes of the People

When faced with such palace coups and machinations, widespread public fury toward an aloof political class is more than understandable. Renzi knew how to use this anger, and as the ‘demolition man’ was able to delight in great popularity for a time. To be sure, Renzi was not born into the upper ranks of the political class. For many years his father was a small-town councilor before he founded a marketing firm in Genoa, where his son also worked before becoming a full-time politician.

Nevertheless Renzi junior quickly learned the intrigues of the trade. Although he gladly presented himself as the representative of the common people, who strikes fear into those on top, he was, however, never elected by the people, at least not as prime minister. On the contrary, he assumed this post from Enrico Letta, winner of the February 2011 parliamentary elections, whom he forced to resign after Letta suffered a serious setback in the election for the Chair of the Democratic Party. With governmental responsibility achieved via a party factional struggle, Renzi turned out to be a palace-revolutionary technocrat in the mantle of a people’s tribune.

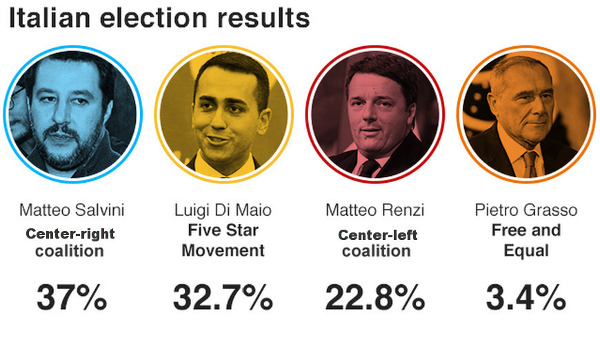

This is a mantle also worn by Beppe Grillo, who is designated by the representatives of the political class as a populist threat to political and economic stability. To forestall such a threat the new elections demanded after Renzi’s resignation were rejected and instead it was declared that despite the failed referendum everything was quite in order after all. Grillo’s Five Star Movement has excellent prospects to emerge as the strongest party in the next elections. In the 2013 parliamentary elections – the movement’s first – it straight away became the second strongest party with 25 per cent of the vote, behind the Democratic Party.

Nevertheless the proposition that Grillo would upend this system is questionable. The authoritarian style with which he leads his movement suggests rather that he could play the cleaned-up populist technocrat just as much as Renzi. Renzi and Grillo represent a type of currently very popular politician who promises fundamental changes but who nevertheless has more of the same discredited policies in mind. Their success can above all be traced back to the lack of a relevant leftwing opposition. Their policies have not only failed in the construction of a halfway solid social consensus, but moreover, they have not even been able to achieve their own economic objectives.

A Mountain of Debt…

The marginalization of the left opposition can be traced back to the support for the governments of Romano Prodi in 1996-1998 and 2006-2008 by Rifondazione Comunista. The aim in both cases was to prevent the return of a Berlusconi government. Both times this goal failed. Instead, Rifondazione shrunk from a party that obtained 6-8 per cent of the vote, to a splitter-party polling just 2 per cent.

A central goal of the first Prodi government was to have Italy – a founding member of the European Economic Community in 1957 – participate in monetary union. In order to comply with the conditionality demanded by the Maastricht Treaty of a maximum debt-to-GDP ratio of 60 per cent, Prodi launched a sharp austerity drive, which was continued by his successors. From the mid 1990s to the mid 2000s, Italy’s state debt was indeed rolled-back to 100 per cent from 120 per cent. Despite these cutbacks in the public sector, unemployment managed to decline from an initial rate of 11 per cent to half of that, while the labour force participation rate climbed from 58 per cent to 63 per cent.

The positive turn in the labour market was however not produced by an uptick in private investment, but by the increasing indebtedness of private households. Its share of GDP rose from less than 20 per cent to about 40 per cent. A portion of the demand that was financed in this way flowed out of the country. The balance-of-payments slid from positive into negative territory. Consequently this was accompanied by a corresponding increase in foreign indebtedness.

…A House of Cards

Since 2008, the recession and euro crisis have quashed this labour market success; state debt climbed again, this time to 133 per cent of GDP. If it seemed in the late 1990s that debt reduction could actually be achieved through spending cuts, recent years have shown the opposite to be correct. Not only did the Italian state have to struggle with revenue shortfalls and the costs of rising unemployment, but it was also confronted with a banking crisis.

Due to ongoing stagnation – Italian economic performance remains well below its 2008 level – private households and firms are increasingly unable to service their debt obligations. In 2008 Italian banks had non-performing loans in the value of €117-billion on their balance sheets, in 2015 this rose to €350-billion. This accounts for about 40 per cent of all outstanding loans.

In 2008 Italian banks held state loans in the amount of €100-billion, in 2015 this climbed to €400-billion. A state heavily indebted to banks has little leeway to take crisis-laden banks under its wing – the more so as the room for maneuver is itself legally limited by the rules of the European Banking Union. Early last year, in desperation, a number of banks compelled small depositors to purchase stock certificates, while the Renzi government tried to convince large-scale capital to launch a bank rescue fund. This enterprise managed to assemble only a meagre €4-billion.

After Renzi’s resignation, the successor government set-up a €20-billion fund for the rescue of the world’s oldest bank, Monte dei Paschi di Siena, which having a non-performing loan to stock equity ratio of 249 per cent faced an acute threat of bankruptcy. The bank’s attempts to scrape up a relatively modest €5-billion on the capital market had previously failed.

Such amounts cannot begin to tackle the private and public debts that have been accumulated. Without political measures that allow for a massive write-down of debts and that simultaneously guarantee the maintenance of current payments, the Italian economy will remain trapped in a debtor’s prison and stagnation. Should it not be possible to scrape together the relatively few euros required to counteract such an acute emergency, it will be shown that the mountain of debt is in reality a house of cards. What is missing is a political force, which out of the ruins of a collapsed house of cards, can build an economy less dependent on debt and more socially just and ecologically sustainable. •

This article originally appeared in the February edition of Sozialistische Zeitung.

Translation by Sam Putinja.